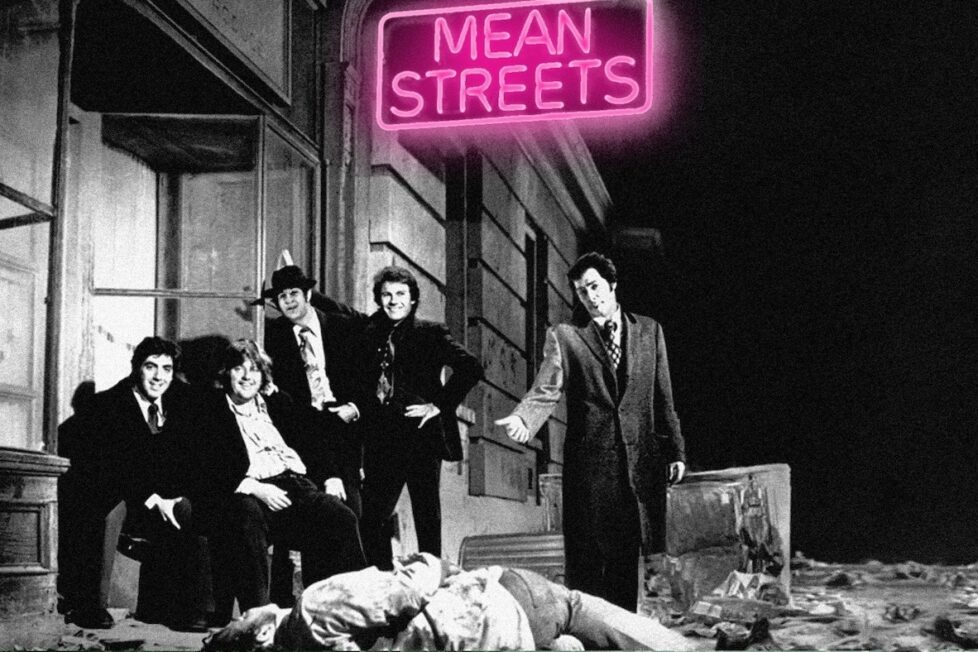

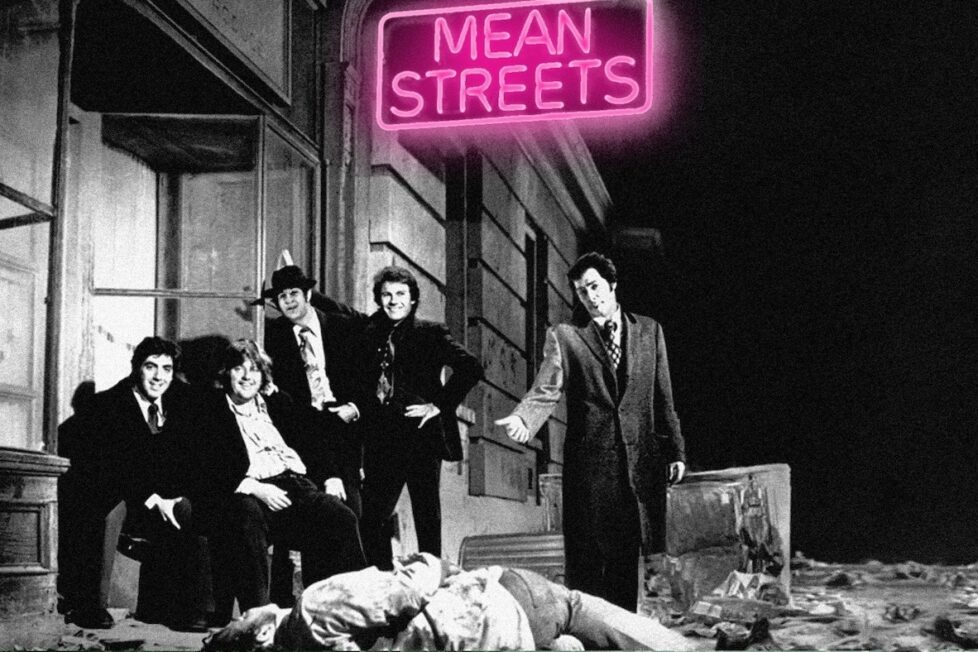

MEAN STREETS (1973)

In New York City's Little Italy, a devoutly Catholic mobster must reconcile his desire for power, his feelings for his epileptic lover, and his devotion to his troublesome friend.

In New York City's Little Italy, a devoutly Catholic mobster must reconcile his desire for power, his feelings for his epileptic lover, and his devotion to his troublesome friend.

The 1960s marked a pivotal moment of reinvention in Hollywood, witnessing the birth of a bold cinematic movement. Fuelled by an increasingly popular academic study of cinema and the global reach of international arthouse films, a generation of daring young filmmakers emerged. This era unleashed an unmatched torrent of creativity, giving rise to iconic figures like Francis Ford Coppola (Apocalypse Now), Steven Spielberg (E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial), and Martin Scorsese. While Coppola’s ambition tested the limits of the studio system and Spielberg revitalised the blockbuster format, Scorsese carved his own path with a series of introspective films exploring diverse themes. His first major critical success, Mean Streets, served as a cinematic breakthrough, showcasing his unique and distinct directorial voice

Following the frenetic production of Boxcar Bertha (1972) for Roger Corman, Martin Scorsese stood at a critical juncture in his burgeoning career. Torn between emulating the grand traditions of classic Hollywood and the gritty realism of European arthouse cinema, he yearned to replicate the mastery of his idols, Alfred Hitchcock (The Birds) and Billy Wilder (Double Indemnity). It was none other than John Cassavetes, known for his raw and intimate films like Love Streams (1984), who delivered a sobering truth bomb. He bluntly told the young Scorsese, “You’ve just poured a year of your life into a piece of trash. You’re better than that. Don’t let the exploitation market trap you. Try something different.” Heeding Cassavetes’s stark advice, Scorsese channelled the same raw energy he poured into his student film, Who’s That Knocking At My Door? (1967), to craft a deeply personal work that immersed audiences in his unique perspective.

Who’s That Knocking At My Door? served as a promising if initially awkward attempt by Scorsese to depict his formative years in Little Italy. However, Mean Streets marked a more ambitious return, a confident retelling of a personal story fuelled by Scorsese’s deeper connection to the material. This second declaration of love for his hometown wasn’t just cinematic; it was forged from the crucible of his own experiences growing up amidst the small-time criminals and aspiring mafiosos of a tightly-knit Italian-American enclave in downtown Manhattan. Scorsese’s screenplay collaboration with Mardik Martin (Raging Bull) became a kind of creative alchemy. Immersed in the sights and sounds of Little Italy, they melded personal struggles with cinematic influences to produce something uniquely potent: an unfiltered and authentic portrayal of New York’s underground criminal world.

In the gritty heart of New York City, Charlie (Harvey Keitel), a low-level cog in the Italian-American community, juggles the contradictions of his life. Faith binds him to Catholicism, yet loyalty compels him to collect debts for his ruthless uncle, Giovanni (Cesare Canova). Guilt claws at him as he tries to salvage his volatile friend, Johnny Boy (Robert De Niro), drowning in debt to the menacing Michael (Richard Romanus) and missing a critical payment. When the church fails to absolve him, Charlie seeks redemption through self-sacrifice, shielding Johnny from Michael’s wrath. But his devotion to Johnny stirs friction with his uncle, tightening the screws on Charlie’s already strained conscience. Torn between the allure of power and the pull of loyalty, Charlie faces a brutal choice: embrace ambition or safeguard his friend.

Mean Streets pulsates with the emotional centre of Harvey Keitel’s (Reservoir Dogs) masterful performance as Charlie. He imbues the character with quiet stoicism and veiled complexity as he wrestles with the crippling guilt woven from his Catholic upbringing. Keitel’s portrayal is deeply sympathetic, exquisitely conveying the internal maelstrom threatening to consume Charlie as he strains to shield those around him.

Juxtaposed against Charlie’s introspective struggle is De Niro’s (Killers of the Flower Moon) electrifyingly charismatic Johnny Boy, a force of nature erupting onto the screen in a fiery explosion of youthful recklessness. This is the De Niro before Hollywood fame, showcasing the raw talent that would later solidify his legendary status. Johnny Boy is a force of nature from the moment he stumbles onscreen and violently destroys a mailbox with explosives. Although his reckless misadventures and gambling debts have placed him on the wrong side of many men, he maintains an insouciant charm that’s instantly likeable.

Scorsese’s name has become inextricably linked to the cinema of New York City. Rarely have filmmakers devoted such a significant portion of their work to capturing its unique blend of Americana and cultural diversity. However, by the time Mean Streets was released in 1973, the city’s cinematic representation was already undergoing a revival. Filmmakers like John Schlesinger (Midnight Cowboy) and Alan Pakula (Klute) used its gritty streets to portray the disillusionment of its inhabitants during a tumultuous decade marked by widespread social unrest. The Big Apple wasn’t yet sanitized by the Rudy Giuliani administration but remained a teeming urban jungle where hustlers, addicts, and criminals thrived in uneasy coexistence.

Unlike his contemporaries, Scorsese confronts the city’s underbelly without flinching, meticulously replicating its atmosphere with an unmatched authenticity. He plunges audiences into the physicality of Lower Manhattan, still segmented by ethnicities, where any “Mook” (“What’s a Mook?”) could spark trouble. A constant sense of danger and violence creeps around the edge of the frame as every conversation can violently erupt without warning.

No viewer could overlook the cinematic imprint of Martin Scorsese in Mean Streets. This, his debut morality tale, sits at the precipice of his burgeoning creative genius, showcasing his most experimental camerawork and turbulent editing. Drawing inspiration from Federico Fellini’s I Vitelloni (1953) and Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (1960), Scorsese establishes a distinct cinematic language that continues to be emulated today. The most prominent echoes of Italian Neorealism and French New Wave lie in Mean Streets’ documentary-like authenticity. Kent Wakeford’s (Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore) handheld cinematography generates a relentless momentum, plunging the viewer into the gritty world of the characters. No sequence exemplifies this effect more than the explosive pool room brawl. As Charlie leads a menacing posse to Joey’s (George Memmoli) establishment to collect a debt, their visit escalates into a chaotic fight. The kinetic camerawork fuels a restless energy, flitting between characters with wild abandon. This invigorating sequence realistically portrays the surreal blend of macho violence while inciting a palpable sense of danger in the audience.

In contrast to the romanticised portrayal of gang life that would characterise his later work, Mean Streets is firmly grounded in gritty reality. While Scorsese wasn’t the first to delve into the schemes of low-level criminals, his departure from earlier fictionalized representations of mob violence undeniably established a lasting authenticity. Coppola had explored the criminal underworld a year earlier with the operatic epic The Godfather (1972), but Scorsese’s approach stands in stark contrast. Unlike Coppola’s romanticised blend of Italian tradition and Shakespearean family feuds, Mean Streets avoids glamorizing the mafia. Instead, it offers an unflinching portrayal of the Italian-American urban milieu under the influence of organized crime. In response to The Godfather, Scorsese remarked, “It was bullshit. It didn’t seem to be about the gangsters we knew, the petty ones you see around. We wanted to tell the story about real gangsters.” The characters in Mean Streets aren’t mythicized by extravagant lifestyles; they’re working-class delinquents struggling to survive by peddling counterfeit goods and illegal fireworks. This rejection of grandiosity is arguably what fuels the enduring influence and appeal of Mean Streets five decades later.

“You don’t make up for your sins in church. You do it in the streets. You do it at home. The rest is bullshit and you know it.”

Central to the world occupied by Scorsese’s characters is the contradictory role of religion. This is unsurprising given the filmmaker’s early flirtation with the priesthood before finding his calling in cinema. His connection to Catholicism explicitly underpins his later works, including The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) and Silence (2016). However, themes of redemption and retribution are most prominent in Mean Streets, particularly in the relationship between Charlie’s successful criminal life and his unwavering commitment to religion. Torn between his fear of divine punishment and his desire for spiritual cleansing, he remains deeply influenced by the church. This is poignantly illustrated in his advantageous attempt at salvation: protecting Johnny Boy from Michael (Richard Romanus). Although Johnny Boy’s soul seems irredeemable, Charlie fiercely maintains his loyalty despite his friend’s lies and transgressions. In doing so, he casts himself as a modern-day St. Francis of Assisi, yearning for atonement. However, the demons that have fallen from God’s grace cannot be easily saved. This truth tragically underlines the film’s breathtakingly cruel and dynamic climax, which acts as a potent symbol of Charlie’s paradoxical existence—a saint amongst gangsters, trapped in his purgatory, forever grappling with the impossibility of escaping his mortal sins. Scorsese revisited similar themes throughout his career in films like Raging Bull, Goodfellas (1990), and Casino (1995), but none captured the essence of this struggle as succinctly as Mean Streets.

Scorsese’s films crackle with relentless propulsion, a rhythm mirrored in his mastery of music. His infectious enthusiasm and encyclopedic knowledge have forged some of cinema’s most electrifying, and even jarring, syntheses of image and sound. Consider Derek and Domino’s haunting “Layla” in Goodfellas, Dropkick Murphy’s rampaging “I’m Shipping Up To Boston” in The Departed (2006), or The Lemongrass’ chilling cover of “Mrs. Robinson” in The Wolf of Wall Street (2013)—each one deepens our connection to his characters, peeling back layers of their psyches in just a few bars.

In Mean Streets, he eschews a traditional score, instead weaving a tapestry of golden oldies and contemporary pop that pulsates with raw energy. From The Chi-Lites’ “Rubber Biscuit” echoing Charlie’s drunken swagger to The Ronettes’ “Be My Baby” hinting at the romantic yearning beneath his macho facade, every needle drop becomes an extension of a character’s identity, while infusing each scene with a potent emotional undercurrent. The crown jewel might be Johnny Boy’s swaggering entrance in Goodfellas, strutting to the swaggering Stones of “Jumping Jack Flash.” This insolently unpolished introduction—arguably one of cinema’s greatest character entrances—stands as a virtuoso display of Scorsese’s sonic storytelling.

While filmmakers like John Schlesinger in Midnight Cowboy (1969) and Dennis Hopper in Easy Rider (1969) used pop music to electrify their narratives, Mean Streets cemented Scorsese’s deployment of music as a groundbreaking storytelling device. He codified this approach, creating a new lexicon that continues to inspire contemporary filmmakers like Spike Lee (Do The Right Thing) and Quentin Tarantino (Pulp Fiction).

Mean Streets transcends a mere rambunctious time capsule of New York City’s Italian-American experience. It’s a groundbreaking masterpiece marking a historically significant moment in Martin Scorsese’s career. His signature trademarks and preoccupations shatter conventions, solidifying his status as a true master of the cinematic medium. While Mean Streets lacks the budget and precision of later successes like Goodfellas and Casino, its influence remains equally pervasive.

USA | 1973 | 112 MINUTES | 1.66:1 | COLOUR • BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

Mean Streets has been given a wonderful 4K restoration courtesy of Second Sight Films to coincide with Criterion’s release from last year. Showcasing an immaculate 2160p Ultra-HD transfer, the image was sourced from the original 35mm camera negative and supervised by writer-director Martin Scorsese and Thelma Schoonmaker.

Presented in its native 1.66:1 aspect ratio, this transfer showcases a beautifully rich image. Viewers will appreciate the presentation’s ability to showcase even the finest of details during intimate compositions. A particular sequence reveals Keitel’s individual eyelashes and the finest blemishes on Charlie’s face. The natural grain structure remains intact and is beautifully rendered to heighten the story’s gritty, urban nature. Despite the darkened interiors, the Dolby Vision intensifies the palette and accurately reproduces the primary colours. Joey’s bar is bathed in overwhelming red hues, whereas the city’s blue neon lights receive a healthy boost. Unfortunately, Criterion’s release attracted some negative comments from several corners of the internet. The consensus was that the colour restoration contained a sepia tone. There aren’t any issues to report here. The presentation is the best it has ever looked and this edition from Second Sight Film is an incredible alternative for UK collectors.

Unfortunately, there’s only one standard audio track on this release with optional subtitles. It’s immediately obvious Second Sight Films has restored the English LPCM 1.0 track. There’s excellent fidelity and a surprising amount of dynamic to the midrange that helps Scorsese’s exquisite choice of music. The intense mix of contemporary pop and Motown surges through the speakers with clarity. The side and rear channels bring significant weight to the supporting sound effects and create an immersive atmosphere. Sonic accents such as startling gunshots and shattering glass are distinct, whereas distant sounds like police sirens are handled nicely. Dialogue is generally clear and discernible remaining primarily at the front. However, the occasional ADR is slightly distorted. Overall, this is a massive upgrade and a welcomed improvement over its predecessor.

director: Martin Scorsese.

writer: Martin Scorsese & Mardik Martin (story by Martin Scorsese).

starring: Harvey Keitel, Robert De Niro, Richard Romanus, David Proval, Amy Robinson & Cesare Danova.