CASINO (1995)

A mafia enforcer and a casino executive compete against each other over a gambling empire...

A mafia enforcer and a casino executive compete against each other over a gambling empire...

Defensive criticism against Martin Scorsese in recent years has erroneously claimed he makes the same film, over and over again. Specifically, the claim’s been levelled against him that he’s gone back to the Mafia as a safety net. While Casino was Scorsese’s third film focussing on the mob, this criticism conveniently ignored that, in between such films, he’s also made films about ambulance drivers (Bringing Out the Dead), hopeless fanatics (The King of Comedy), and deities (The Last Temptation of Christ and Kundun).

The claim took hold after Scorsese stepped on some comic-book fanboy toes last year, signalling that perhaps it’s a reactive criticism, rather than genuine. It also incorrectly takes as wisdom that films by a director that follow a similar subject are therefore the same film. This is like saying that Schindler’s List (1993) and Saving Private Ryan (1998) are the same film because Steven Spielberg directed both, and because they’re set during World War II. It’s obviously untrue, but if you’re looking to criticise a director in the easiest way possible, this might be the stance you’d take.

Even when Casino came out in 1995, there were those who bemoaned its resemblance to Scorsese’s earlier Goodfellas (1990). On the surface, this might hold water: there’s the same brutal violence, the ascent and descent of a crooked businessmen, and frequent needle drops. It’s there, but it’s cosmetic. Of course, these things point to a director, just as the works of any auteur (if you buy into auteur theory, anyway) signal the person behind the camera. This doesn’t engage critically with the fact that Casino, like Goodfellas, Mean Streets (1973), and The Irishman (2019) are their own films, concerned with wildly different aspects of criminality and redemption.

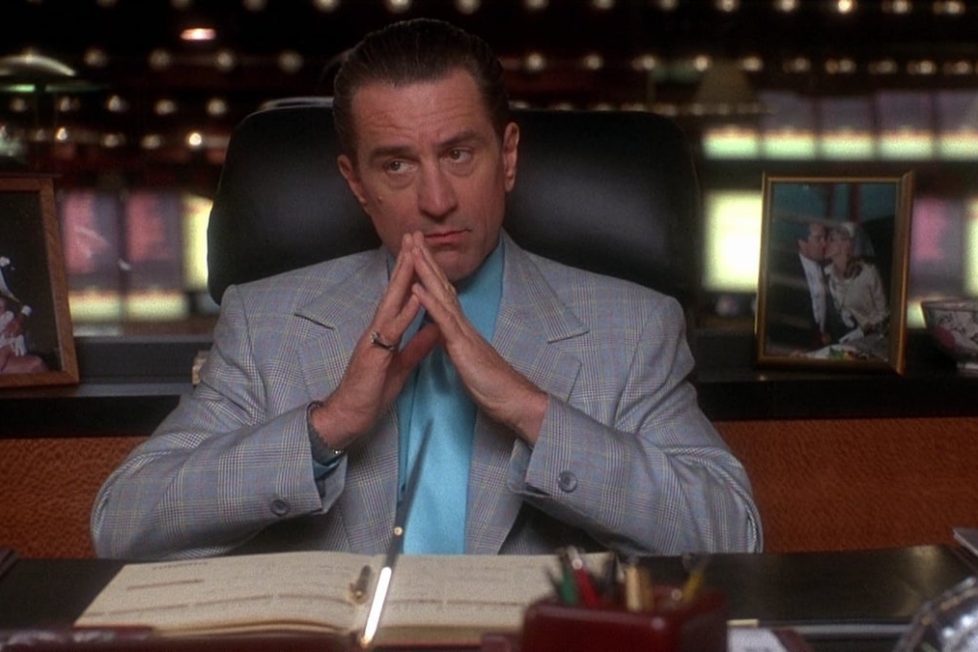

Scorsese and screenwriter Nicholas Pileggi based Casino on a true story, as he’d done with Goodfellas. But Casino is more of an historical document, concerned with lifting a veil that exists between the glitzy, tourist-friendly allure of Las Vegas and its seedy underbelly. Charting the rise and fall of Sam ‘Ace’ Rothstein (Robert De Niro) through his tenure as a casino boss in 1970’s Las Vegas, the film goes deep into the money-skimming scams, shakedowns, and backhanders that kept the money and business flowing. But look beyond the hands smashed with hammers (you might literally want to) and heads crushed in vices, and Casino‘s a film about jealousy and possession. The gorgeously detailed period-accurate costuming and set design are captivating, while getting the scoop on the secrets of the trade is luridly fascinating—but it’s the human thrust of the film that gives it specificity and depth.

Sam’s closest friend, Nicky Santoro (Joe Pesci), is hellaciously angry when he wants to be, but almost more unsettling is his unexpected tenderness. It’s this which draws in Ginger McKenna (Sharon Stone), Sam’s deeply unhappy wife. A truly ill-advised love triangle ensues, and forms the crux of Casino. As The Sopranos (1999-2007) later refined, mobsters are just as fascinating—if not more fascinating—when they’re at home. Casino has a warped domesticity about it, which begs the question of how people like Sam separate their business relationships with their personal ones, if there’s even a distinction between the two. Ginger’s as much an acquisition of Sam as a new house is; property and a means to exert power. The idea he might lose her to someone else is less about love and more about greed and ownership. It’s the modus operandi of someone who makes their living by owning every stage of production in a rigged system.

Casino develops beyond the sub-genre of crime biopic when it fills in blanks, and pushes its characters beyond what is known about them and into what feels true. Scorsese and Pileggi based Sam on the real life figure Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal; a casino boss, sports handicapper, and all-round dodgy-dealer. A lot of the film lifts directly from real events. For example, the car bomb assassination attempt on Sam actually happened to Frank, and the almost unbelievable thwarting of the attempt was, at least according to Frank, true as well.

The love triangle, Ginger’s downfall, and the film’s most shockingly brutal kills were tragically accurate. As with so many of the great films based on a true story, it’s the kernels of truth at the centre and the window-dressing around it which is essential, and the blanks are filled in with creative license. One of the film’s most memorable sequences (a vicious fight between Sam and Ginger on their front lawn) was itself the initial inspiration behind the entire project. Pileggi read a newspaper article about the real-life fight between Frank and Geri (whom Ginger is based on), and used it as a fuel to dive deep into the personal and business lives of the Las Vegas mob. It’s telling that a domestic disturbance is what inspired the screenplay, and knowing the fact gives further weight and tragedy to the relationships between Sam, Ginger, and Nicky.

The way the story of Casino is told, across its spacious yet propulsive three hours, brings into focus a sort of reversal of Goodfellas trajectory—while that film’s about a world being built, and about work damaging one’s personal relationships, Casino is about a world falling apart and the dissolution of personal relationships and how that pulls down everything around it. In Casino, the crumbling of Sam and Ginger’s marriage is as catastrophic and final as the old casinos that collapse dramatically in controlled demolitions.

In a 1995 interview with Charlie Rose, Scorsese calls it’s a film about “the end of Vegas” and “something like an urban western, where it was really the end of the old Wild West.” That sense of change is inherent with gambling, chance, and luck. A gambler might be up by hundreds one moment and down by thousands the next. Even for those who are riding high, the system is waiting with its jaws wide opened, ready to chew them up and spit them out into the barren deserts which surround Vegas. That process is what America is built on; a false hope that you might make it, and that if you do, you’ll stay on top forever, happy and untouched by life’s troubles. It’s easy to ignore the dust and death of the desert when the lights of the city are that bright.

Scorsese dazzles and seduces you before throwing you into a dingy backroom where a big guy with a hammer is waiting. Similarly, the halcyon days of an eccentric romance are offered up, but as romantic and beguiling as it all is, with all its money and cars and sex, it all feels terribly doomed. De Niro and Stone are electric together. The sparks between them are uncomfortable, because they could just as easily be sparks of violence as sparks of passion. Stone’s performance carefully balances Ginger’s outsized personality with intense vulnerability, while De Niro presents Sam as someone who wants the world, but doesn’t want the attention. He wants to take everything that you have, but not to make a big thing out of it. He can have it, because it’s his.

In one scene, Sam frustratedly complains about his muffin not having as many blueberries in it as the next muffin. It’s an inconsistency that he can’t abide by. Sam wants more blueberries, yes, but he also wants control, of something as large as a casino, and as trivial as a blueberry muffin. It smacks of desperation, the sort of desperation that comes from a man who knows his industry is dying. Meanwhile, Nicky, as vile as he is, tries to be a voice of reason to the unravelling Sam. It might be Pesci’s finest performance. Nicky has the bark of little dog and the bite of a big one, but he also has the insecure wounded qualities of a dog who’s been hit on the nose one too many times. He and Ginger are a mistake waiting to happen, both of them vulnerable and with an enemy in common, but Nicky exerts his waining power over Ginger nonetheless. He works in Vegas; he’s used to taking advantage of situations.

Casino gives us a sweeping, bird’s-eye-view of things. It opens with a fiery explosion, only to jump back in time and leave the aftermath of said explosion until the very end. It couldn’t be more fitting: Casino is watching a disaster happen in slow motion. It’s the end of an era, crumbling under its own weight, and the end of a trio of people, screwed over by poor choices and uncontrolled emotions, a sort of last gasp before dying, like De Niro at the end of Cape Fear (1991) submerging madly below the waters of the lake.

It’s all cyclical though. Scorsese hilariously shows us swaths of elderly gamblers spilling into the casino in dramatic slow motion, after the mob rule of the city has died. It’s not that the snake-eating-its-own-tail manner of capitalism has ended, it’s that it has been repackaged and rebranded as friendly, a fun holiday for the elderly and honeymooning couples. It is no less predatory and the practices are no less mercenary than they once were, only now visitors feel comfortable because surely the government wouldn’t allow bad practices to occur for profit, right? Scorsese and Pileggi’s script perhaps bleakly suggests that one mob has been replaced by another, and that there are probably other Sam Rothsteins making their bones just as unconscionably.

The satire is caustic, but again, it’s the studiousness of character and motivation that sets Casino apart from Scorsese’s other mob films. It’s rich with insight and endlessly fascinating in its portrayal of desire run amok. Scorsese is not a didactic director. In fact, his refusal to scold has even made people wonder if his film The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) celebrates the lifestyle it depicts (hint: it doesn’t), but anyone paying close enough attention to his work and his beliefs will understand exactly what Scorsese is saying: that greed is the ultimate destructive force and that nobody is invulnerable to its power. Casino is the struggle of people trapped inside this battle and the question of whether they can ever cleanse themselves of it.

Casino was well reviewed when it was released, but not to the same degree as some of Scorsese’s previous work. Even now, it’s not talked about as much as his other mob film, or indeed Taxi Driver (1976) or Raging Bull (1980). I wonder if this might be because Casino‘s character work is more subtle, and it’s plotting more complicated and, for want of a better word, technical. It’s world-view requires deeper digging and it’s generally a dark and troubling film. It doesn’t wash down as smoothly as Goodfellas, and nor should it.

Nonetheless, Casino is enjoying a reappraisal, thanks in part to The Irishman‘s recent critical acclaim. It deserves to be talked about and remembered, not as a lesser work of a great artist but as a vital work by one of the great living filmmakers. It’s easy to fall into the trap of comparing a director’s works, but ultimately, Casino stands on its own. It doesn’t live in a vacuum, but it is not a copycat, nor a retreading of old ground. In fact, watching it in 2020 makes clear that sometimes distance and time is needed for a film to blossom, and for its ideas to become even more pertinent. Today, it might even be my favourite Scorsese. That title changes a lot though, so I won’t bet on it. I wouldn’t want Sam getting in on my action.

USA • FRANCE | 1995 | 178 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Martin Scorsese.

writers: Nicholas Pileggi & Martin Scorsese (based on ‘Casino: Love and Honor in Las Vegas’ by Nicholas Pileggi).

starring: Robert De Niro, Sharon Stone, Joe Pesci, Don Rickles, Kevin Pollak & James Woods.