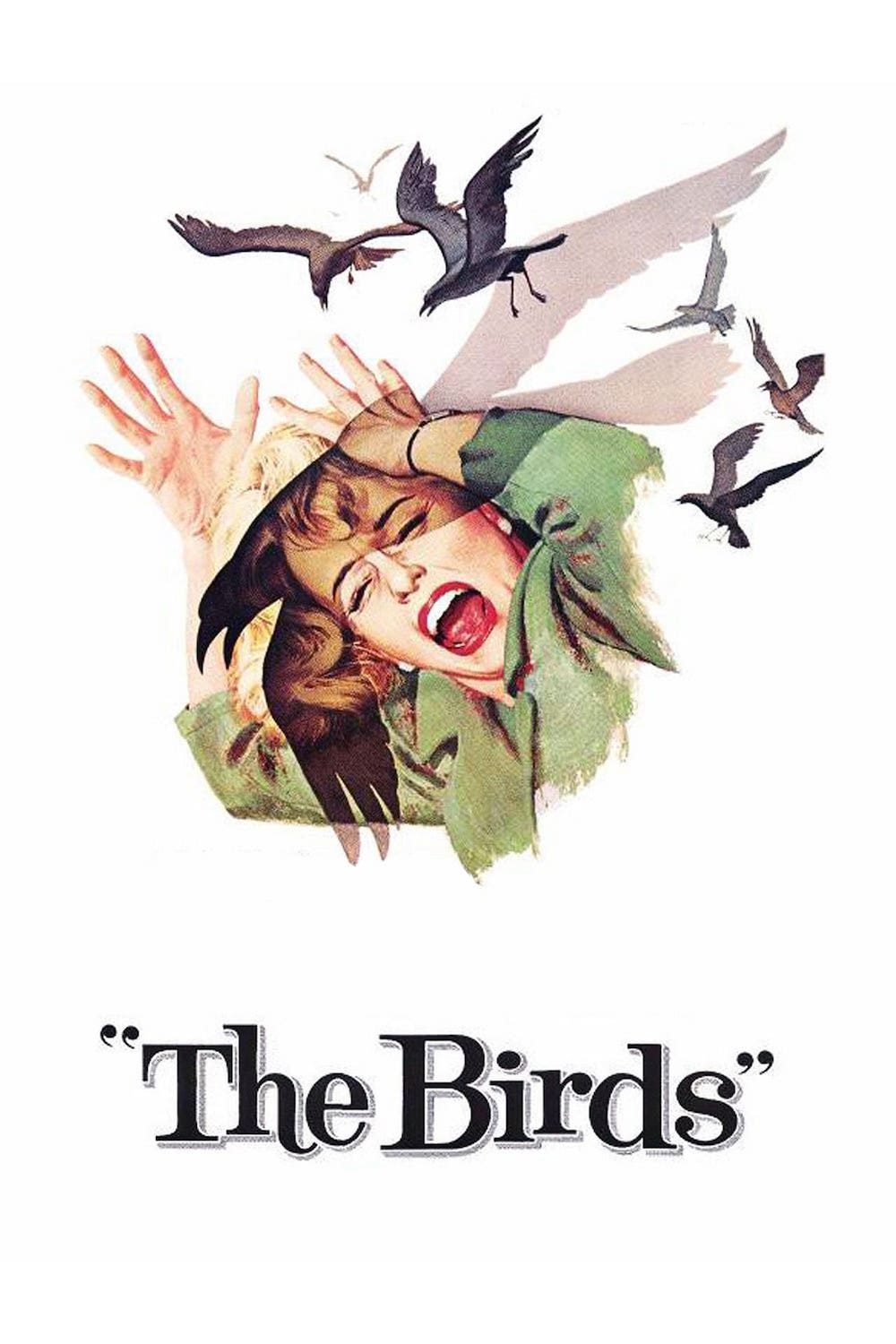

THE BIRDS (1963)

A wealthy socialite pursues a potential boyfriend to a small coastal town that takes a turn for the bizarre when birds start attacking people.

A wealthy socialite pursues a potential boyfriend to a small coastal town that takes a turn for the bizarre when birds start attacking people.

On 18 August 1961, a swarm of seabirds attacked the small seaside town of Capitola, California. Residents ran for cover as gulls dive-bombed them, smashing windows of houses and cars. In a particularly vivid account, fearful Capitola residents watched as the birds, seemingly distressed or in some bizarre state of avian psychosis, vomited partially digested fish across their lawns.

Unsurprisingly, Alfred Hitchcock, the “Master of Suspense,” found this to be the perfect inspiration for his magnum opus: The Birds. As part of the promotion for his final horror film, Hitch proudly declared it the most terrifying film of his career.

In the end, while his 1963 horror-thriller wasn’t his best work—or anywhere close to his most terrifying—it’s certainly impressive even today. Undoubtedly, much of the praise is due to the simple fact that an effects-driven horror movie can remain believable 60 years later. However, an important point to note is that, while it’s clear Hitchcock intended to turn flocks of seagulls, sparrows, and crows into menacing villains, whether he succeeded is debatable.

The Birds begins in a bird shop, where our two protagonists, Melanie Daniels (Tippi Hedren) and Mitch Brenner (Rod Taylor), meet for the first time. Immediately drawn to each other, Melanie decides to surprise Mitch with a pair of caged lovebirds for the weekend he’s spending at his Bodega Bay home. But when she arrives, she finds herself caught in the middle of a terrifying natural disaster: the local seabirds have turned carnivorous and are attacking people.

Unexpectedly, the catastrophe in The Birds doesn’t happen until well past the hour mark. This isn’t necessarily a problem, as Steven Spielberg hid the T-Rex in Jurassic Park (1993) for a similar amount of time. However, there is a crucial difference: a confrontation with the king of the Cretaceous was inevitable, while the tone of The Birds feels disjointed because the first hour is dedicated to establishing the characters, a family drama, and a love story, with only a few hints given to the airborne horrors to come.

This results in a meandering first half. Supposedly, Hitchcock believed that since audiences would be aware of the inevitable avian assault (the title was a clear giveaway), he could delay the scares and keep audiences in suspense until much later on. However, there’s an argument to be made this created an unbalanced film with a muddled atmosphere. What starts off feeling more like an erotic thriller, soon turns into a small-town folk horror a la The Wicker Man (1973), only to become a natural disaster/monster movie. But by that point, the narrative work hasn’t been done to establish the birds as terrifying creatures. Hitchcock conflates creating a suspenseful tone with omitting to build up his titular antagonists.

The inherently unthreatening nature of seagulls hampers Hitchcock’s attempt to turn them into movie-level monsters. While I’ve often found seagulls annoying, I’ve never found them frightening or even dread-inducing. Hitchcock’s task is further hindered by the fact that even dangerous animals aren’t necessarily scary. The distinction is important because the tension of The Birds rests on the audience’s fear of the next malicious attack. When the audience doesn’t fear the seagulls, parts of the film can drag or even become unintentionally amusing. For example, when the seagulls swoop inland to take advantage of a car explosion in a seemingly orchestrated manner, the scene feels almost like a monster movie parody.

Hitchcock’s mastery of suspense is evident throughout the film, despite the challenges posed by the subject matter. For example, the scene in which Lydia drives out to check on her neighbour is expertly crafted, building tension with every shot. The broken teacups in the kitchen, the long hallway, and Lydia’s tentative approach to the bedroom door all contribute to the sense of impending doom. The climax of the scene, in which Lydia finds her neighbour’s eyeless corpse, is both shocking and tragic.

At a later point in the story, the Brenner family and Melanie are huddling together to escape the onslaught of murderous birds when the three Brenner family members fall asleep. This leaves Melanie alone to hear the distinct sound of rustling feathers. Like a detective, she shines her flashlight on the two caged lovebirds, but they are innocent. The muffled sounds are clearly coming from upstairs. Melanie’s slow, anxious ascent up the stairs is one of the quintessential scenes of dread in cinema. The ominous light on the wall, her delicate turning of the handle, and our own apprehension, as we await the inevitable, create a truly suspenseful moment.

Hitchcock’s film isn’t bad, but he fails to turn our dread of birds into outright horror. Most of the terrifying reveals are not that terrifying, with one or two exceptions. Unfortunately for Hitchcock, he wasn’t making a story about a great white shark, which is the perfect real-life monster for intimidating audiences as we discovered 12 years later with Jaws (1975). A few finches simply don’t have the same impact, especially today.

One could argue that the objects of our fear, the birds, are onscreen too much without doing anything. Of course, the birds huddle together on telephone lines like a watchful portent of doom, but familiarity breeds apathy. We know they’ll attack soon, and watching them in their passive state robs them of any dramatic oomph. In contrast, the shark in Jaws was only seen on camera for four minutes, whereas we spend a large portion of The Birds watching birds lounging about like hoodlums on a street corner. Nevertheless, Hitchcock manages to turn even these moments of potential tedium into cinematic brilliance. For example, as Melanie waits for Cathy in the school, she turns around to be greeted by a playground of crows, which is a spectacular surprise.

Despite losing some of its scare-factor over the past 60 years, The Birds remains an excellent film with much to enjoy. Its technical achievements, particularly the special effects, are still impressive today. Even though the $200,000 mechanical birds used in some scenes aren’t always convincing, intelligent editing helps to cover the gaps. For example, the chaotic birthday party scene is a masterclass in suspense, with Hitchcock using close-ups and rapid cuts to create a sense of impending doom.

Compelling performances from Tippi Hedren, Rod Taylor, and Jessica Tandy assist Hitchcock in his attempts to frighten us with squawking fowls. Hedren, making her feature film debut, is remarkably composed and in control, from her lines of dialogue to her physicality. Taylor switches effortlessly between a smooth-talking lawyer and the concerned head of a family, while Tandy’s portrayal of Lydia Brenner remains steady to the end, even if some moments verge on overacting.

Most of all, Veronica Cartwright, who was only 13 when she played Cathy Brenner, delivers a surprisingly convincing performance as a young girl caught in the middle of what appears to be, by all accounts, the apocalypse. Her teary-eyed, distraught portrayal never becomes loud, petulant, or irritating as many child performances in horror movies do; instead, she adds much-needed dramatic heft in some of the quieter scenes. As she begs Mitch to bring the lovebirds with them as they flee Bodega Bay—“They never hurt anyone!”—one can sense the weight of their plight on her young shoulders. Unsurprisingly, Cartwright’s mature performance was well-recognised and she went on to become a notable name in science-fiction horror, starring in Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978) and Alien (1979).

As Mitch listens to the radio, he learns that almost everyone has evacuated the seaside village, leaving them the last humans in a town now ruled by birds. The drunken Irishman’s proclamation in the restaurant has come true: the end of the world is here. Mitch hesitantly walks his sister, mother, and love interest to the car. He releases the handbrake and coaxes the car down the hill, quietly. Bodega Bay has been abandoned, relinquished to its feathered adversaries.

And just like that, the film ends. We’re provided no revelation, salvation, or epiphany. Slumped and defeated, the Brenner family and Melanie Daniels limp away and the curtain closes behind them. Of course, the cause of the event that inspired a large portion of this film was subsequently divulged years later: the host of seagulls that attacked Capitola had eaten toxic algae, resulting in a curious case of kamikaze avifauna. However, the murderous events that transpire in Hitchcock’s rendition of what was a real-life freak occurrence in nature are never explained, nor hinted at.

At early stages in script development, it was considered that the townsfolk of Bodega Bay harbour a terrible secret. As such, the plight of the birds could then be recognised as some sort of divine punishment. Though this idea was eventually scrapped, the vestiges of it can be found at the beginning of the story: throughout the first act, one might expect Melanie’s amid a sinister seaside cult. This ominous atmosphere of an insular, parochial community, exhibiting inquisitive gazes and questionable smiles, ensures the introduction of all major characters is infused with a foreboding air.

Later on, as the seagulls attack Bodega after the locals ruminate on their situation in the diner, we can see the remnants of this idea filter through yet again. Melanie and Mitch retreat into the restaurant where a collection of thirteen women and two children huddle in fear. The distressed mother—who truly hams it up, even for the 1960s—turns to Melanie and confronts her, saying “They said when you got here the whole thing started… who are you? What are you? I think you’re the cause of all this!” The story takes on an aura of a Greek tragedy: the people of Bodega Bay appear to be the object of a cruel god’s wrath, punishing them for their hubris—or the secret that was ultimately written out of the script—and the dozen cowering women act as the mute, catatonic Greek chorus.

Film scholars have interpreted the inexplicable bird attacks in The Birds in various ways. Andrew Sarris suggested that the birds punish the inhabitants of Bodega Bay for their hubris, complacency, and lack of appreciation for nature. Hitchcock supported this interpretation, but it is unclear when the citizens display disdain for nature.

Hitchcock’s decision to deny the audience an explanation for the bird attacks improves the film. It allows the film to become about whatever the viewer interprets it to be, which was Hitchcock’s intention. A feminist reading would be apt, as would an interpretation that connects the film to the African-American Civil Rights movement of its day. However, the analysis that seems most applicable in today’s times is that of ecological disaster and subsequent fallout. Was this Hitchcock’s intention? We may never know, but the film’s prescience is undeniable.

The Birds is a classic horror film that deserves to be seen for its historical significance and technical mastery. However, it is no longer as terrifying as it once was. The film’s palpable tone and unsettling atmosphere are still effective, and the characters and performances are all excellent. The dour ending and bleak mood of the latter half of the story create a powerful sense of spiralling despair, but not terror.

USA | 1963 | 119 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Alfred Hitchcock.

writer: Evan Hunter (based on the novel by Daphne du Maurier).

starring: Rod Taylor, Jessica Tandy, Suzanne Pleshette & Tippi Hedren.