KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON (2023)

In 1920s Oklahoma, white men scheme to rob the oil-rich Osage tribe of their newfound wealth...

In 1920s Oklahoma, white men scheme to rob the oil-rich Osage tribe of their newfound wealth...

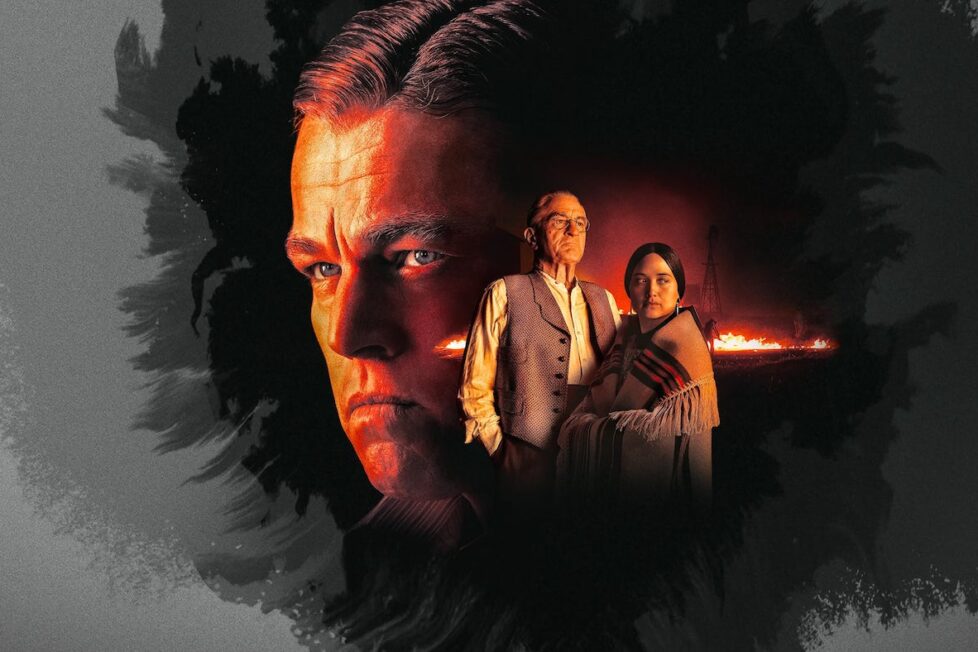

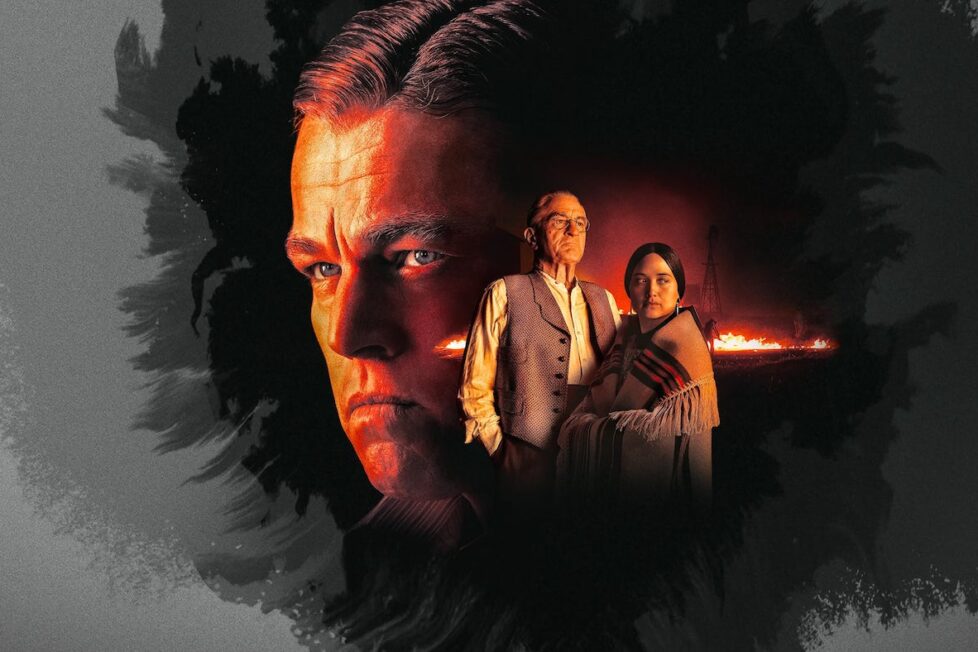

At the start of Killers of the Flower Moon, Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio) arrives in Oklahoma to live with his uncle, William Hale (Robert De Niro). Freshly discharged from the US Army after World War I, Ernest is earnest, simple-minded, and leafing through a children’s book about the Osage Indians…

The book’s caption asks the reader “Can you find the wolf in this picture?”, and by then the audience has likely guessed that the wolf is Hale. So when Ernest tells his future wife, Mollie (Lily Gladstone), that Hale is “a nice man”, it reveals more about Ernest’s naivety and his sealed fate than it does about Hale’s true nature.

Killers of the Flower Moon deals with one of Scorsese’s favourite subjects (crime) and explores one of his favourite themes (guilt). But it has more in common with The Irishman (2019) than with his earlier, more rambunctious crime sagas like Goodfellas (1990), and not just in their nearly identical runtimes.

Like The Irishman, Killers of the Flower Moon is the story of a man who becomes a gangster by accident, against a backdrop of events much bigger than him. DiCaprio’s Ernest is essentially boring as a dramatic character in himself, an obedient soldier without unusual motivations or even many traits. As with De Niro’s Sheeran in The Irishman, we are never quite sure whether to like him, dislike him, or simply pity him.

What makes him interesting is the situation he stumbles into, and the contrast of his character with the more complex and devious man who controls him. In The Irishman, that was Joe Pesci’s Mafia boss; in Killers of the Flower Moon, it’s De Niro playing Ernest’s uncle. And just as with Sheeran in The Irishman, the dilemma into which Ernest’s loyalties have dragged him is only clear to him in retrospect, as he realises that he was always a pawn, peripheral to something larger than his own ambitions.

The two films share more similarities than just these two characters. Like The Irishman, Killers of the Flower Moon is a chamber piece despite its sweeping scope. The wide-open Oklahoma spaces are quietly impressive, but nearly all the important action occurs in small rooms, where the subtleties of individual relationships and single acts unfold.

Much attention will naturally be paid to the movie’s depiction of white exploitation of Native Americans, and the extent to which it still represents a white perspective on the issue despite its good intentions. However, it’s a mistake to view the movie solely through this thematic, macro lens.

It’s the micro details that matter. As Sheeran discovered in The Irishman and Ernest and others tragically learned in Killers of the Flower Moon, real life unfolds through a series of small details and choices, a seemingly invisible structure that becomes clear only in hindsight. The systematic injustice inflicted on the Osage people provides the backdrop for Killers of the Flower Moon, but the stories operate at the individual, human level. De Niro’s Hale may have made a fatal error in underestimating the power of small things to derail grand plans.

Based on Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by the American journalist David Grann, Scorsese’s film takes place in Oklahoma in the years immediately following World War I. This is an interesting coincidence, as The Power of the Dog (2021) by Jane Campion was also set in the American West during the same time period. Could this be a sign that the Western genre is expanding into later periods as the 1920s move further away from living memory?

Ernest returns from the war, where he served as a cook, to join his brother Byron (Scott Shepherd) and Hale at the latter’s ranch. Hale is wealthy, but the Osage tribe on whose land his ranch sits is even more so. They are fabulously, impossibly wealthy, unable to spend their money fast enough, thanks to the discovery of oil on their territory.

However, though this may make them fortunate compared to other Native American groups, it also makes them ripe for exploitation—not least by Hale, who feigns a benign, avuncular interest in them but is secretly and ruthlessly scheming to take over their “headrights” (i.e. shares of the oil revenue). He quickly draws Ernest into his criminal activities and also encourages him to woo and marry Mollie (Gladstone), a young Osage woman who stands to inherit headrights when some of her family die; Hale reasons that if he facilitates these family deaths through murder and also has Mollie herself killed, then the headrights will pass on to the easily manipulable Ernest.

Despite Hale’s plan, Ernest unexpectedly falls in love with Mollie. Meanwhile, Osage leaders are alarmed by the number of murders in the community, apparently committed by whites—in reality, some 60 over a four-year period, extending beyond Hale’s plot against Mollie’s family. More broadly, they worry about the influence of white culture on the Osage. Eventually, the federal government, which has some responsibility for affairs on Native American land, is persuaded to intervene, and the FBI launches its first homicide investigation.

Killers of the Flower Moon offers no new or remarkable insights into the white treatment of Native Americans. The deceit, abuse, and rapacity are all well-known. To some, it may only seem like a movie “about” these topics because they (and issues relating to race and minorities in general) are so prominent in the current conversation.

In truth, the film’s greatest strengths are its characters and performances. The writing and production design are highly persuasive but understated, while the direction, photography, and music are restrained. Even the Oklahoma landscapes, which were filmed in mostly authentic locations, are not overly spectacular.

The film reunites two of Scorsese’s most frequent collaborators, De Niro and DiCaprio, and while the older man is perfectly cast as Hale, it’s DiCaprio’s Ernest who steals the show. Reportedly, DiCaprio was originally cast as the FBI agent, eventually played (predictably well) by Jesse Plemons, but lobbied for this larger role instead. He’s just as right for it as De Niro is for Hale. (That said, one could easily imagine Plemons as Ernest as well.)

DiCaprio’s performance as Ernest is far from boring, despite the character’s essential dimness. He deftly avoids overplaying Ernest’s dullness, while still conveying his character’s lack of intelligence (as evidenced by Ernest’s inability to grasp Hale’s complex plan). Ernest is often nervous and a terrible liar, but he can also be determined. However, his determination often fizzles out before he can take action. Fundamentally, Ernest is a weak man, as easily manipulated as the Osage are for different reasons.

De Niro’s Hale, almost a less exaggerated version of Daniel Day-Lewis’s Plainview in There Will Be Blood (2007), is as different from Ernest as possible. A determined man playing a very long game with some success, Hale is also a great liar. His hypocritical pretences at piety and treating the Osage as equals (he even speaks their language) are well-acted, and his race-based view of the world (he believes in white destiny, that the Osage have had their time) is so well-concealed that the film hardly ever lets it out into the open, though we might guess at it anyway.

Despite his intelligence and cunning, Hale isn’t immune to self-deception. He seems to genuinely believe that the Osage love him (which implies he also believes they’re very stupid), and he’s equally convinced that no white man (least of all Ernest) could ever outmanoeuvre him. It’s no surprise that he, too, ends up as isolated as Frank Sheeran in The Irishman.

Gladstone delivers a much quieter but equally captivating performance as Mollie. At first, she is low-key, combining impatience and amusement with Ernest, but it’s clear that she possesses both depth and intelligence. Later in the film, when her life takes a tragic turn, she blends these qualities with a greater vulnerability, almost despairing. As a symbol of betrayal and resistance, she’s at the heart of the movie, and even though it largely offers a white perspective, we also get hers.

Many other fine performances come from the supporting cast, including Yancey Red Corn as an Osage leader whose oratory Scorsese uses powerfully to convey the group’s concerns without being overly didactic. Cara Jade Myers is feisty and resentful as Anna, Mollie’s sister; William Bellau convincingly and sadly portrays the melancholic and self-loathing Osage Henry Roan.

On the white side (and they’re mostly divided into “sides” in this film), Shepherd consistently hints at a horribly cruel streak in Ernest’s brother. Sturgill Simpson (who was the subject of a funny running joke in Jim Jarmusch’s 2019 film The Dead Don’t Die) is striking as Henry Grammer, a henchman of Hale. Grizzled Ty Mitchell is another henchman, surprisingly a dedicated family man. Jason Isbell is sinisterly polite as a white man who, like Ernest, marries an Osage. Gene Jones is wonderful as the thoroughly corrupt and unlikeable legal guardian of Mollie’s headright. (The Osage were not considered capable of managing their own money.)

Throughout Killers of the Flower Moon, Scorsese sprinkles in telling directorial touches. In one beautiful, underplayed scene, a dying Osage woman sees the spirits of her ancestors. In another, a horse panics at the sight of newfangled automobiles. And in a courtroom scene, the cacophonous argumentativeness of the proceedings suggests that justice is not always well-considered. Scorsese even includes excerpts from a silent newsreel called “Fox News,” a real name that may not be a coincidence.

With the possible exception of an odd epilogue set in a radio studio, where Scorsese himself appears to get the last word, very little in Killers of the Flower Moon is self-indulgent or flamboyant. The film is mostly straightforward, and even the occasional quotable line (“Our blood is getting white,” laments a senior Osage) is the exception. Many developments, such as the growth and modernization of the town near Hale’s ranch, happen in the background without any passing of comment. Scorsese is more interested in showing us the world of his film than in telling us what to think about it.

The merging of Roman Catholic and Osage elements in a wedding ceremony is simply presented, for us to draw our own conclusions. Even some significant plot points are oblique and barely signalled in the screenplay, co-written by Scorsese and Eric Roth (adding to Roth’s impressive filmography, which ranges from 1999’s The Insider to 2020’s Mank). Viewers must pay close attention to Killers of the Flower Moon.

And they will. Despite its long runtime, the film needs its length and never drags. Arguably, it could have even benefited from more minutes. The main flaws, though not fatal, are structural. Eventually, the film largely loses sight of Mollie’s story in favour of Ernest and Hale’s, and it switches from a contemplative pace to a more rushed, fact-cramming mode about an hour before the end.

This awkwardness, along with Scorsese’s decision to take a back seat to the actors and storyline, means that Killers of the Flower Moon is unlikely to go down as one of his greatest films. However, it’s so well-written and well-acted, with direction that supports and enhances the narrative rather than drawing attention to itself, that it’s certainly one of the most absorbing of recent westerns. It’s also an interesting complement to The Irishman and further proof of Scorsese’s sometimes underappreciated versatility.

USA | 2023 | 206 MINUTES | 2.39:1 • 1.33:1 | COLOUR • BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH • OSAGE

director: Martin Scorsese.

writers: Eric Roth & Martin Scorsese (based on the book ‘Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI’ by David Grann).

starring: Leonardo DiCaprio, Robert De Niro, Lily Gladstone, Jesse Plemons, Tantoo Cardinal & John Lithgow.