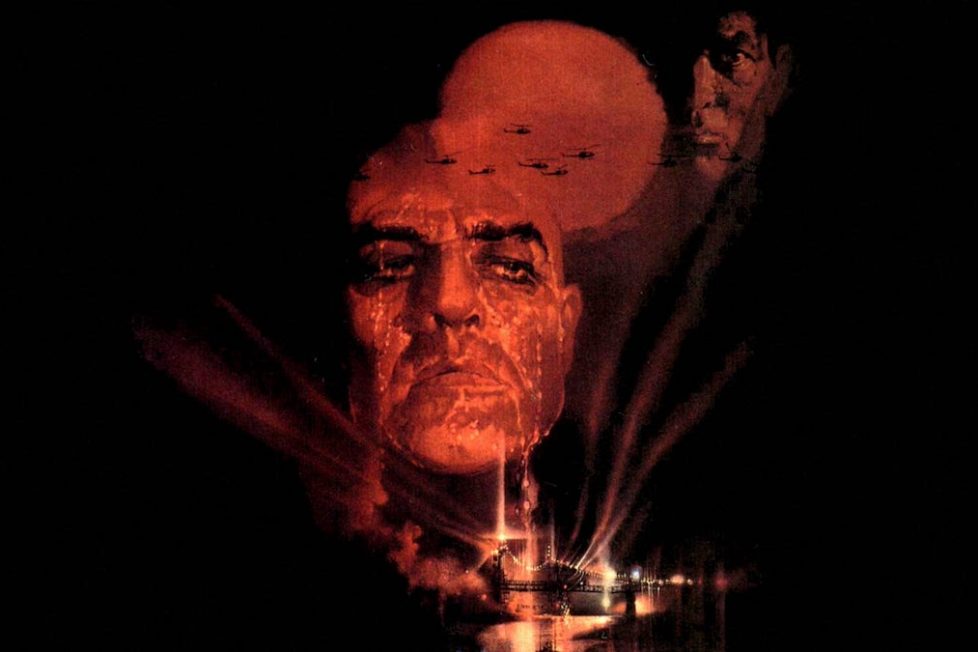

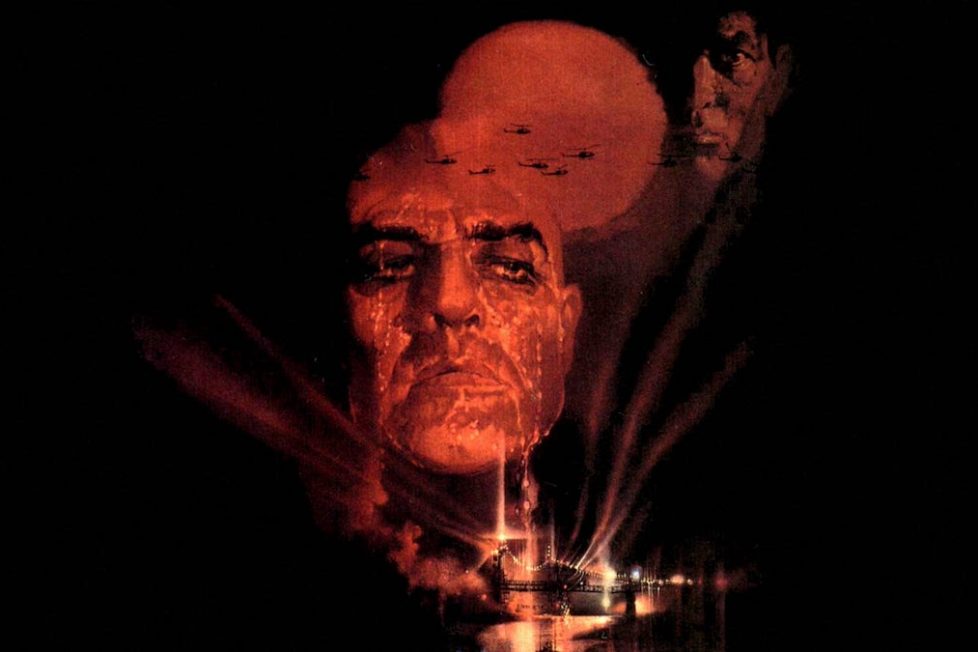

APOCALYPSE NOW (1979)

A US Army officer serving in Vietnam is tasked with assassinating a renegade Special Forces Colonel who sees himself as a God.

A US Army officer serving in Vietnam is tasked with assassinating a renegade Special Forces Colonel who sees himself as a God.

The blades sound like nothing else. The pulse of sound, cutting through the silence, sounds more like the alien hum of a spaceship than the blades of a helicopter. If air is chopped up and redistributed by these blades… then so is time, sent swirling through Captain Benjamin Willard’s (Martin Sheen) mind. A piece of haunted music joins the churn: the gentle, sinister opening chords of The Doors’ “The End“.

The fire that envelops the palm trees is silent. Scenes from Willard’s past are not past, they’re living, current and engulfing. In his room, with only bottles of alcohol and his own beaten reflection to keep him company, Willard relives it all. With this new final cut of Apocalypse Now, so do we. Almost everyone will be familiar with some element of the film, be it “The Ride of the Valkyries” helicopter sequence, “… the smell of napalm in the morning”, or the image of Willard rising slowly from the river and its fog. If the familiarity is not from their relation to the story then surely it is from their placement as cultural icons, existing seemingly separately to the film itself.

To experience, or re-experience these icons today is almost a contextualising exercise, like taking objects and finding a place and function for each of them within a room. Director Francis Ford Coppola has asked us to do this before. In addition to the original 1979 cut of the film, Apocalypse Now: Redux appeared in 2001 containing 49-minutes of extra footage, creating what appeared to be Coppola’s final version. But now, 18 years later, we have Apocalypse Now: The Final Cut, which trims several Redux scenes and upscales the film to crisp 4K.

Arguments over which version of the film is definitive are endless and answerless, forever stoked by Coppola’s revisits. A perfectionist, the director routinely repositions the iconography of the film as if it were a living work of art. His doing so gives the film a mercurial allure, as if each time you see it, it will have mutated into something else: a war film, a psychological odyssey, or a poisoned fairytale.

It’s worth considering how far removed Coppola is from Willard. Both men are called by a destructive obsession with a past that they know nearly killed them. So hellish was the film’s year-long shoot that Coppola contemplated suicide on several occasions. And here is Willard, similarly self-destructive, shattering a mirror with his fist in a drunken stupor, obsessed with the patterns of blood on his hand. The moment was real; Martin Sheen was plied with alcohol as the cameras rolled. His inebriation was genuine, as were his tears and blood.

Here are men—fictional and real—paralysed by war and the recreation of war. Coppola positions filmmaking as if it is its own war; self-inflicted, hubristic and, in this case, annihilating. They’re drawn to it not because it’s all they know, but because it’s such an altering force that it obfuscates everything else. So here we find Coppola, heading back down the rivers of time into the heart of darkness for perhaps one last journey.

Regardless of the conjecture over which cut of the film is most essential, or valid jokes about Coppola’s self-importance, Apocalypse Now: The Final Cut is worth another trip. On a filmmaking level, it’s simply unimpeachable. Despite its undeniable haze of 1970s intensity, the film feels contemporary in its craft. Some scenes appear as tableaus, so still and measured are they, while others have a carefully controlled dynamism that blows the stillness to smithereens. Cinematographer Vittorio Storaro patiently explores Willard’s face with the depth of a painter.

Weathered but youthful, Willard is studied by Coppola’s camera like a washed-up movie star. We’re scared of his violence but desperate to get at that dimly-fading inner light. The humid sun that smothers him in the early scenes will later be lost to shadows, a striking visual charting Willard’s descent into hell. The images are crisp and stunning, but often something keeps us separated from them. At times it’s a shallow focus, while others its darkness. The visual language draws us inwards to Willard, constantly trying to understand and see him. He’s in a cinematic prison.

Sheen gives such a bruised performance that it can be upsetting to behold. This isn’t a man who’s on the way down—this is a man who’s already at the bottom. His voice in narration is gruff yet high-toned, aged way beyond its years—as if the fire and smoke of war live in his throat. It’s an astonishing performance, pulling off the difficult feat of being the centre of a film that has no centre; a core that has dropped out and is now a gaping hole. No goodness or badness is retained. Just action motivated by impulse.

The complexity of an amoral protagonist is amplified by Coppola’s scenes of war, which are conflictingly exciting, yet distressing. Mostly, they’re non-partisan. Apocalypse Now doesn’t feature dying soldiers having the comforts of home described to them, and its ‘heroes’ (if there are any) feel no remorse in the killing. Instead of some jingoistic speech meant to rally the troops, Colonel Bill Kilgore (Robert Duvall) is concerned with the tides and surfing. He fires indiscriminately from his helicopter at civilians, soldiers, whoever. It’s a game; a task to be completed, a landscape to be conquered, a tide to be surfed. Their actions are appalling, but Coppola’s film is about the part of these people that’s died, and the film is bleak and unsentimental to match that absence.

As the boat moves further up the river, the film’s pace reaches a bottleneck. Moving past army outposts and abandoned Medvac centres, time slows to a transfixing crawl. Even at three hours, the film never feels overlong. Indulgent perhaps, but a necessary indulgence that gives space to breathe and suck us in, pushing us slowly along the murky water. On this odyssey, everything becomes dreamlike, or perhaps nightmarish. Enemies amongst the trees are unseen now, and fire spears instead of guns. One sequence sees the soldiers staying overnight with a family of French plantation owners (a segment added for Redux) and, though initially jarring, it heightens the sense of surreality. As if they were dining with forgotten ghosts who refuse to acknowledge their transience.

And as Willard and his slowly diminishing crew move towards Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando), who Willard’s been ordered to kill, they’re not unlike ghosts themselves. Willard reads files on Kurtz as if they were clippings from magazines, with him playing the part of besotted fan come to kill his idol. The last chapter of the film, set in Kurtz’s outpost, contains some primally powerful filmmaking. Coppola allows us to feel the weight of each character by way of their introductions; incomparable to any other is Kurtz, his looming face barely identifiable in the darkness of his bunk.

Kurtz and Brando couldn’t exist without each other. Willard has travelled on a hypnogogic journey to a core of horror, and at the nucleus found the man behind the curtain; not a Wizard, but a man. A snake-oil salesman selling his customers well-worded nonsense. A despot. Brando famously improvised most of his lines and shaved off his hair for the part. “I don’t see any method at all, sir,” Willard tells Kurtz in the film’s most ironic line. There is some Brando in Kurtz, and Kurtz is likewise given the legend-making grandeur that Brando received as an actor. And here is this younger actor, coming to overthrow—or replace?—this old Hollywood relic. There’s a casual iconoclasm here that’s thrilling.

The film’s finale is heady and fittingly apocalyptic. Kurtz and Willard are driven by similar impulses, damaged by the same horrors. To kill Kurtz would be a metaphorical suicide for Willard. To not kill him and to listen to his teachings would theoretically be the same. He’s either a killer for the army or a killer for Kurtz. It’s a Catch-22. His ego-death has occurred and here is the apocalypse along with it; he is already damned.

The final scenes are edited with electrifying tension. The cross-cutting between Willard acting upon his decision and the sacrifice of the buffalo gives a gut-wrenching sense of inevitability and succumbing. The mass of humanity is lit by brilliant spotlights from the boats, the rain falling like clear blood. The most iconic image of the film—Willard emerging from the river like an animal—is breathtaking. It’s the kind of shot that tells an entire story and is one of the best examples of Coppola relaying so much information in just one frame. He tells his story visually, primally, and instinctively. It could almost be told without words.

But there are words. Some of the most important of those are spoken by Kilgore earlier in the film: “One day this war will end”. It’s said with sadness. Of course, it won’t. For the people of Vietnam, it never truly would. For soldiers, shell-shocked and mired in horror, it wouldn’t end. And as a country, America’s war would never end, atrocities paving the way for more atrocities. Apocalypse Now is a film that will never end—even if this is the final cut. It will always be an essential work of art to revisit… alive and ever-changing… as elusive and mysterious as the words that Kurtz speaks. The film’s thoughts might be some of the bleakest and terrifying ever expressed in mainstream cinema, but if our fascination is endless, then perhaps there are some truths in its dark heart. We can never resist the allure of getting out of the boat.

director: Francis Coppola.

writers: John Milius & Francis Coppola.

starring: Marlon Brando, Robert Duvall, Martin Sheen, Frederic Forrest, Albert Hall, Sam Bottoms, Larry Fishburne & Dennis Hopper.