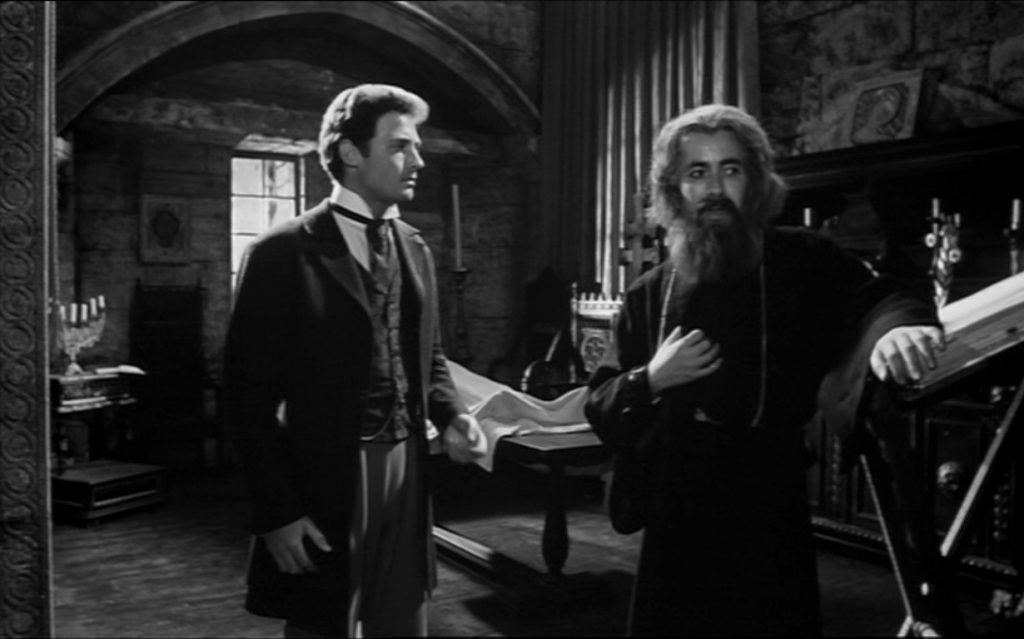

THE MASK OF SATAN / BLACK SUNDAY (1960)

A vengeful witch and her fiendish servant return from the grave and begin a bloody campaign to possess the body of the witch's beautiful look-alike descendant, with only the girl's brother and a handsome doctor standing in her way.