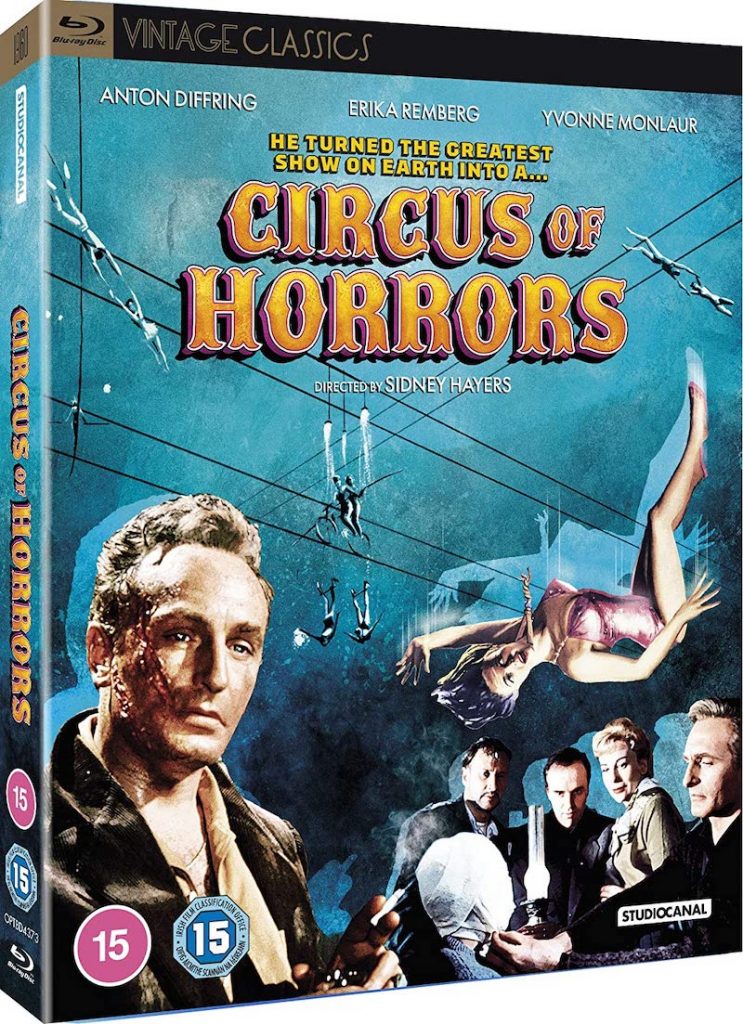

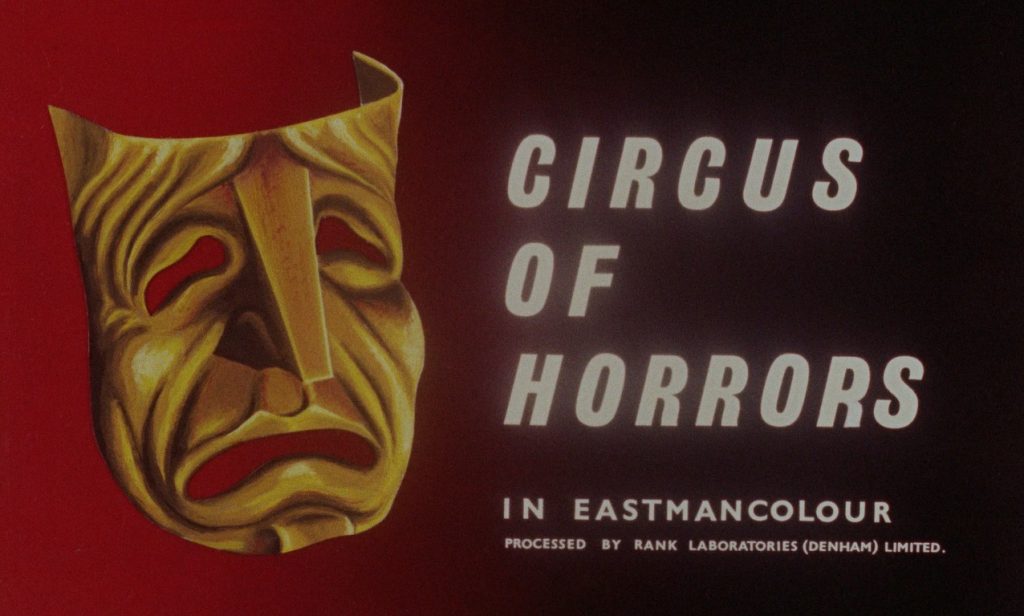

CIRCUS OF HORRORS (1960)

In 1947 England, a plastic surgeon flees to France when one of his patients has ghastly problems with her surgery.

In 1947 England, a plastic surgeon flees to France when one of his patients has ghastly problems with her surgery.

Not a great film, but I have a soft spot for Circus of Horrors because it prefigures so many great horrors and thrillers that followed. It’s definitely a British horror of note and deserving of digital preservation, scanned in 4K from the original camera negative, as the latest Blu-ray release on Studio Canal’s ‘Vintage Classics’ label. Although some elements that shocked on its release are now laughable, it may induce unease in today’s climate of political correctness, albeit for different reasons than 60 years ago. If you can get past that, though, it remains brashly entertaining.

A plastic surgeon, on the run after a botched operation, assumes a new identity and acquires a failing circus, which he uses as cover to continue his crazy medical work in secret. Harvesting patients from the desperate classes of criminals and prostitutes, he turns women who’ve been disfigured by bomb blasts or malicious mutilations into paradigms of beauty. They become the star attractions in his circus. He then bends them to his will by means of blackmail or, failing that, silencing them permanently in engineered ‘accidents’. That brief synopsis runs the risk of making it sound even more bonkers than it is…

There are some striking visuals right off the bat, including a lingerie-clad woman screaming and smashing mirrors in her boudoir and an incendiary car crash, but the first 15-minutes or so are marred by torrents of clumsy exposition desperate to get the backstory out of the way. The principal cast all step up to the challenge of delivering this dire dialogue and manage to elevate a poor script to almost Shakespearean levels with their full-on, gutsy performances.

However, Anton Diffring mostly underplays his lead as a rogue plastic surgeon, Schüler. He’s all cool blue gaze on the surface and deranged maniac underneath. A chilling balance that Diffring had perfected by playing numerous Nazi villains in several notable war films like Break to Freedom (1953), The Colditz Story (1955), and The Beasts of Marseilles (1957). Being a gay Jewish refugee who’d escaped Germany ahead of the outbreak of war, Diffring knew first-hand how chilling and threatening the Nazis were and memorably resurrected his stereotypical role for The Heroes of Telemark (1965) and Where Eagles Dare (1968).

Diffring’s association with such roles, along with his genuinely Germanic accent, hints at Schüler’s past as a Nazi doctor, perhaps experimenting in some concentration camp. The character claims to have trained in Zurich but is quickly established as an unreliable narrator. Diffring had only just ventured into horror starring as Baron Frankenstein in the pilot for a never-produced 1958 TV series, Tales of Frankenstein. On the strength of this, he was cast in the lead role for the Hammer film The Man Who Could Cheat Death (1959) after Peter Cushing pulled out at the last minute.

The always reliable Donald Pleasence makes an all too brief, though pivotal, appearance in the opening act. He loads his alcoholic, failing circus showman with pathos and manages to elicit heartfelt pity even as he dies in the embrace of a man in an ill-fitting bear suit. Later, there’s a man in a gorilla suit that’s a little more convincing, though not believable enough to raise a chill instead of a chuckle.

Such scenes play out as comedy for a modern audience and only add to the fun! Indeed, Circus of Horrors is very much a film of its day and no longer seems as controversial and envelope-pushing as it did in the 1960s. What it does remain, though, is hugely enjoyable—if you’re in the right mood for it. The mad story never lets things drag and more than makes up for any shortcomings in the SFX department.

Spurred on by the success of their first foray into the horror genre, Horrors of the Black Museum (1959), Anglo-Amalgamated Productions were looking for something with a similar sadistic vibe and saw the potential to set themselves up as the main competition to Hammer’s grab for the British Horror movie market. They were looking to produce movies with the same transatlantic appeal as their series based on Edgar Wallace mysteries which sold to ABC Cinemas, and through Rank distributors as B Movies. These were also bringing in steady revenue from television sales in the US as The Edgar Wallace Mystery Theatre.

Edgar Wallace tended to write macabre thrillers with no supernatural aspects, in which the horror stemmed from purely human evils. This approach placed Anglo-Amalgamated in a different niche to their Hammer rivals. Nevertheless, they never really cemented a reputation for horror, probably because their most successful films around the same period, by far, were the first dozen comedy films in the Carry On franchise. Oddly, their forays into horror and comedy both took advantage of changing times and attitudes, sharing risqué elements that challenged attitudes to sex and violence.

Hammer horrors tended to be period pieces, whereas Anglo-Amalgamated favoured contemporary settings. Circus of Horrors is set during a Britain in transition. Traditional values were eroding, increasingly questioned by a generation that had come of age during wartime. That war had been fought for freedom from fascism, yet that fascism had too many parallels to the nation’s own imperial past.

The double standards of the 1940s and uptight morality of the reactionary 1950s were being called-out. The times they were a’ changin’, but the ’60s certainly weren’t swinging yet. Just like the women in the film, and numerous soldiers who returned from the front, the national identity had been scarred.

Surely, after the upheaval of the world wars, things couldn’t simply go back to how they were. Post-war rationing had only ended in 1954 and by 1956 Britain was flirting with war again in a bid to take control of the Suez Canal. Then, there was the escalating war in Vietnam, continually in the headlines.

Circus of Horrors does seem to reference these themes, including the socio-economic repercussions of war and European cooperation to address crimes committed in the recent past, though never formulates any cogent response. The script went through several rushed rewrites, some of them so last-minute that it was never deemed ‘finished’, even as production began. And it shows.

For teleplay writer George Baxt, Circus of Horrors was his first foray into the feature film format, apart from contributing some dialogue to Hammer Film’s Revenge of Frankenstein (1958). He clearly looked to the German Horror film Phantom des Großen Zeltes (1954), a reworking of the classic Phantom of the Opera story. In the early marketing material for Circus of Horrors, it was even promoted with a near translation of the same title, Phantom of the Circus.

Though Baxt’s dialogue leaves much to be desired, he uses the circus setting to good effect. It drives many key elements of the plot whilst drawing some clever parallels with the horror genre. As one of the generation who spent many a depressing Bank Holiday watching Billy Smart’s Circus on the telly, I doubt I’m alone in finding such imagery innately creepy and disquieting. Particularly the performing animals. The biggest selling point of Bernhardt Schüler’s circus, after his famous ‘Temple of Beauty’ sideshow, is that it’s plagued by bad luck and there have been a series of fatal tragedies in the big top. All involving young, beautiful women.

After two B Movies, this was the first full-length feature for director Sidney Hayers and he goes at it with gusto. He makes no excuses for this overtly misogynistic thread and positively relishes the visual poetry of bright red blood tricking over feminine curves. This is an excellent early example of the subgenre we now know as ‘exploitation cinema’.

The studio already knew that sex and death were a bankable combination. So, just like the audiences we see in the film (which for the most part were real punters from Billy Smart’s Circus), we too are salaciously watching the buxom beauties with the added frisson of anticipated violence and bloody death. It’s a formula that would be recycled by the likes of Dario Argento and, just like a classic giallo, Circus of Horrors offers up its murders as contained ‘set-pieces’—-not dissimilar to the separate acts in a real circus.

Apart from simply allowing the gorgeous Eastmancolour cinematography of Douglas Slocombe to wash over you, the most fun can be had spotting the stars and starlets in supporting roles and cameos.

Schüler’s, henchman, Martin, who reluctantly does his deadly dirty work, is played by Kenneth Griffith—-a face that’ll be familiar to British audiences. Though probably hard to place, having been a fixture of the small screen from the 1930s, up to his final appearance in a 2003 episode of Holby City.

I knew him as Number Two from “The Girl Who Was Death”, an episode of The Prisoner (1967-68), and also his graduation to The President for the series finale, “Fall Out”. Fans of The Prisoner will also recognise Peter Swanwick, playing Inspector Knopf, from his recurring role as the Supervisor of The Village.

Inspector Knopf is the German policeman who suspects Billy Smart’s—um, I mean, Bernhardt Schüler’s Circus as being a front for dastardly deeds. (Clever how the circuses have the same initials so ‘stock footage’ of Billy Smart’s could be used without its hoardings spoiling the continuity!) Before Knopf manages to gather enough evidence, though, the circus moves on to England.

The German police tip-off British Intelligence and as soon as Schüler erects his Big Top, Inspector Arthur Ames (Conrad Phillips) is on the case. Phillips is another one of those recognisable faces, which isn’t surprising given that he made well over a hundred appearances in UK film and TV over a career spanning five decades. At the time he was well-known as the titular character in all 39 episodes of ITC’s William Tell (1958-59). The following year he would appear in John Gilling’s The Shadow of the Cat (1961), also written by George Baxt.

Ames had investigated a case of botched facial reconstruction surgery years before and suspects there is a connection with Doctor Rossiter, who disappeared shortly after, and the mysterious Schüler. He follows this hunch by getting intimate with a few of the women appearing in the ‘Temple of Beauty’ so he can examine them for the tiniest of tell-tale scars. Any excuse, eh! However, he develops genuine affection for Schüler’s beautiful ‘niece’ Nicole, who’s actually the daughter of the circus’s original owner.

Nicole is perhaps the only honest and likeable character in the film and, really, it’s her story as we see her grow up from a young girl with a scarred face (Carla Challoner) into a beautiful ‘adolescent’ (Yvonne Monlaur). With Circus of Horrors, Monlaur graduated from ‘Euro-starlet’ and was briefly in demand as a Hammer horror leading lady, appearing opposite Peter Cushing’s Van Helsing in Brides of Dracula (1960) and starring with Christopher Lee in Terror of the Tongs (1961).

Melina (Yvonne Romain) is the statuesque beauty whom Schüler recreates as his perfect partner in a nod to Pygmalion. She adds an extra romantic dimension and manages to melt his icy heart, presenting him with a shot at redemption. But what is it about her that he finds so captivating? Could it be that all he really admires is the result of his own work? She’d made around 20 films using her real name, Yvonne Warren, including a small part in Pickup Alley (1957) and she’d already appeared with Anton Diffring in The Beasts of Marseilles.

Capitalising on her exotic beauty, she changed her name to Romain for her role in Circus of Horrors and it was the part that really got her noticed, so the moniker stuck. Her next big-screen role was the female lead in Hammer’s The Curse of the Werewolf (1961) with another Hammer film, Captain Clegg (1962), following the next year.

She worked consistently in film and TV through the 1960s, including a starring role in the Elvis vehicle Double Trouble (1967), with her final film being The Last of Shiela (1973), in which she played the title role. She then decided to retire from acting to concentrate on family life, famously turning down Federico Fellini’s offer of a seven-year contract.

The pre-release marketing made much of the cast of sexy starlets to be showcased in Schüler’s ‘Temple of Beauty’, along with the promise of lurid violence shot in gloriously gory colour. The violence isn’t at all extreme by today’s standards and there’s actually very little blood on the screen, but it still has a taint of sadistic sickness here and there.

Audience expectations, along with an unlikely hit single taken from the soundtrack ensured Circus of Horrors was a surprise box office hit in the US. “Look for a Star”, the theme song written by Tony Hatch (under the pseudonym of Mark Anthony) was released by four different artists and all those versions managed to chart at the same time! In addition to the film version by Gary Mills, there was a knock-off sung by a ‘Gary Miles’ which managed to outperform the original, another cover by Deane Hawley, and an instrumental version by the Billy Vaughn Orchestra.

Spurred on by the success of their formula, Anglo-Amalgamated Productions immediately followed-up with the superior Peeping Tom (1960), Michael Powell’s ground-breaking neo-giallo about a psychopathic photographer who gets his kicks by filming women’s reactions to witnessing their own deaths. Then they took a step back from horror for a few years.

Perhaps it was the backlash as British censorship tightened-up in response to a rash of such films released that year, including Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) and Mario Bava’s The Mask of Satan (1960). But probably it’s simply down to the huge popularity of their naughty Carry On romps. Later, they would go into co-production with American International Pictures for my two favourites of Roger Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe adaptations, The Masque of the Red Death (1964) and The Tomb of Ligeia (1964).

UK | 1960 | 92 MINUTES | 1.66:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

For this 2020 restoration of Circus of Horrors, Studio Canal went back to the original camera negative which was scanned at 4K to produce a brand new HD master. The sound and vision are nicely cleaned up and it certainly looks and sounds better than ever before. I particularly enjoyed the luscious colour saturation.

However, there are glitches that must’ve resulted from mechanical damage whilst shooting or processing, the most obvious being a recurring vertical line in the left side of the picture. This artefact is evident even in publicity prints, so it’s obviously been there a long time. It really doesn’t distract and I actually enjoy seeing surviving grain and minor scratches on prints of classic films, reminding the viewer this was shot more than half a century ago, on proper analogue film. It only adds to the nostalgic appeal.

director: Sidney Hayers.

writer: George Baxt.

starring: Anton Diffring, Erika Remberg, Yvonne Monlaur, Donald Pleasence, Jane Hylton & Jack Gwillim.