PSYCHO (1960)

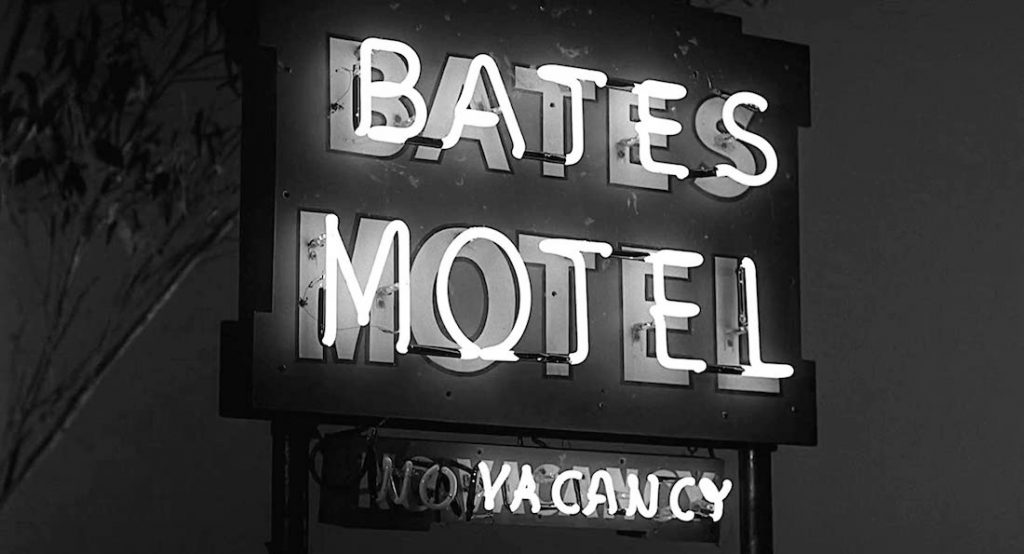

A secretary embezzles forty thousand dollars from her employer's client, goes on the run, and checks into a remote motel run by a young man under the domination of his mother.

A secretary embezzles forty thousand dollars from her employer's client, goes on the run, and checks into a remote motel run by a young man under the domination of his mother.

Alfred Hitchcock’s 47th film, Psycho, is one of those rare movies to have entered the mass consciousness, being familiar even to those who’ve never seen it. Most of this is down to one scene: the notorious murder of Janet Leigh in the motel shower, which was utterly shocking to audiences in 1960 and still delivers a wallop today.

It’s the turning point of the film. The point when Psycho changes from being a drama about a mundane crime into something patently horrifying, as a crazed woman bursts through Leigh’s shower curtain wielding a knife. And the way its violence shatters a potentially upbeat moment is also decisively important in explaining the enduring power of the film.

Until then we’ve followed the character of Marion (Leigh) closely, from an unhappy lunchtime assignation with her boyfriend Sam (John Gavin), through her decision to steal money from her employer, to her flight through the Arizona desert and the California night, and eventually her arrival at the Bates Motel, where she shares a snack with the charming young manager Norman (Anthony Perkins). He leaves her alone in her room, and Marion now decides to give the money back, before stepping into the shower to symbolically wash away her crime. The more famous crime of Psycho follows soon afterwards, of course, with Marion becoming one of many ‘Hitchcock blonde’ victims or near-victims.

The brief and legendary shower scene gains its power not only from sheer surprise, or the extreme whiteness of the surroundings contrasted with the implicitly red blood (Psycho is shot in black-and-white), or the quick-fire editing so unusual for the time, or Bernard Herrmann’s screeching strings on the soundtrack, or the unexpected death of a big star like Leigh less than halfway through the movie, or the equally ground-breaking shot of a flushing toilet shortly before the attack on Marion. All of these are important, sure, but it works so well because it comes at precisely the point Marion’s resolved to start fixing her problems in a way that’s more sensible than stealing the cash ever was. And yet this is for nought: her hopes of redemption are torn apart by a knife in the shower.

The remainder of Psycho is spent, in literal plot terms, on the investigation of Marion’s disappearance by Sam, his sister Lila (Vera Miles), and the detective Arbogast (Martin Balsam). But the atmosphere has completely changed. The motel and its surroundings, once a refuge for the fleeing Marion, is now tainted by the crime and its aftermath (Norman cleaning up the bathroom and concealing Marion’s car). The house where Norman lives with his mother has gone from a picturesque curiosity into an almost caricatured haunted mansion.

As the critic William Pechter put it, Psycho becomes suffused with the sense that “something awful is always about to happen”, and by the time its 109-minutes are over audiences are in no doubt the film they’ve watched is a bleak and almost nihilistic one. It’s a movie of decrepitude and desperation. Another writer, Charles Taylor, observed wisely that although it’s explicitly set just before Christmas, there’s no reference to the festivities.

The shower scene remains its key, something Hitchcock must have known, given he spent seven days of the short schedule (originally planned as just 36 days) on crafting it, and set up 70 different camera positions for less than a minute of footage. For Psycho fans, however, many other scenes are just as memorable…

There’s the opening, where the camera seems to spy on Marion and Sam in their hotel room. As Hitchcock, who was always interested in voyeurism, said in his interview with François Truffaut, “it allows the viewer to become a Peeping Tom”, and prefigures more spying that’ll come immediately before the shower murder. Norman even refers to “cruel eyes studying you”, suggesting that none of the characters is immune from this distressing intrusiveness, and making the viewer wonder about their own morality in feasting on such private moments as the lovers’ post-coital chat or Marion’s ablutions.

Then there’s Marion’s long drive, retrospectively as much a journey into the heart of darkness as Martin Sheen’s voyage along the river would be in Apocalypse Now (1979) nearly two decades later, and her nail-bitingly suspenseful interrogation by a cop hidden behind sunglasses. The misdirection here is a wonderfully Hitchcockian touch: we’re led to believe that the discovery of Marion’s theft is a big threat, but it turns out to be the least of her problems and, in some ways, the stolen money is itself nothing more than one of the director’s famed MacGuffins.

Then there’s the conversation between Marion and Norman, where—more misdirection—one might be forgiven for detecting an early spark of romance between these two unhappy individuals.

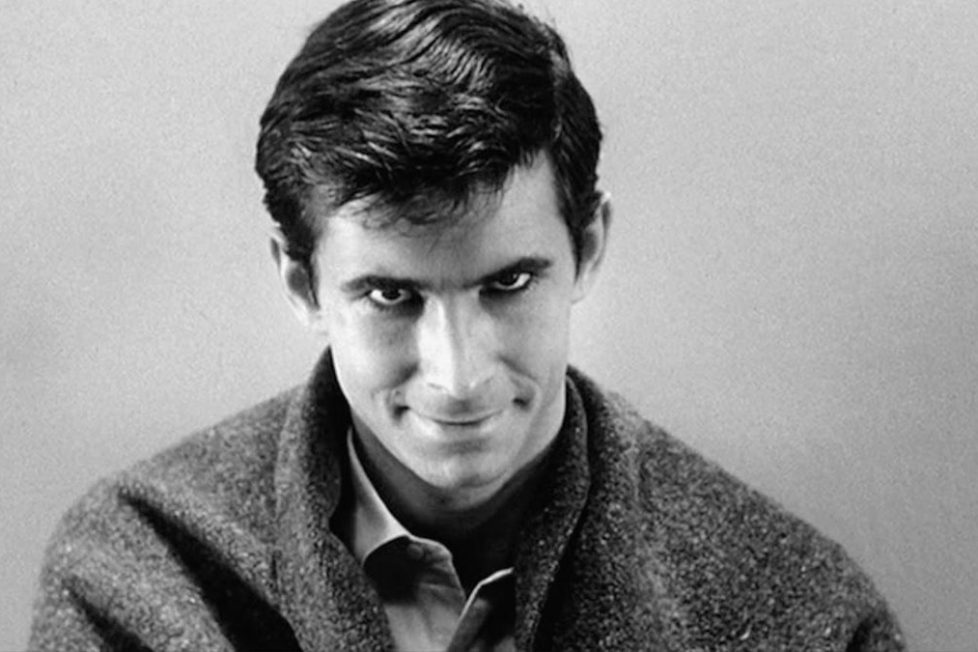

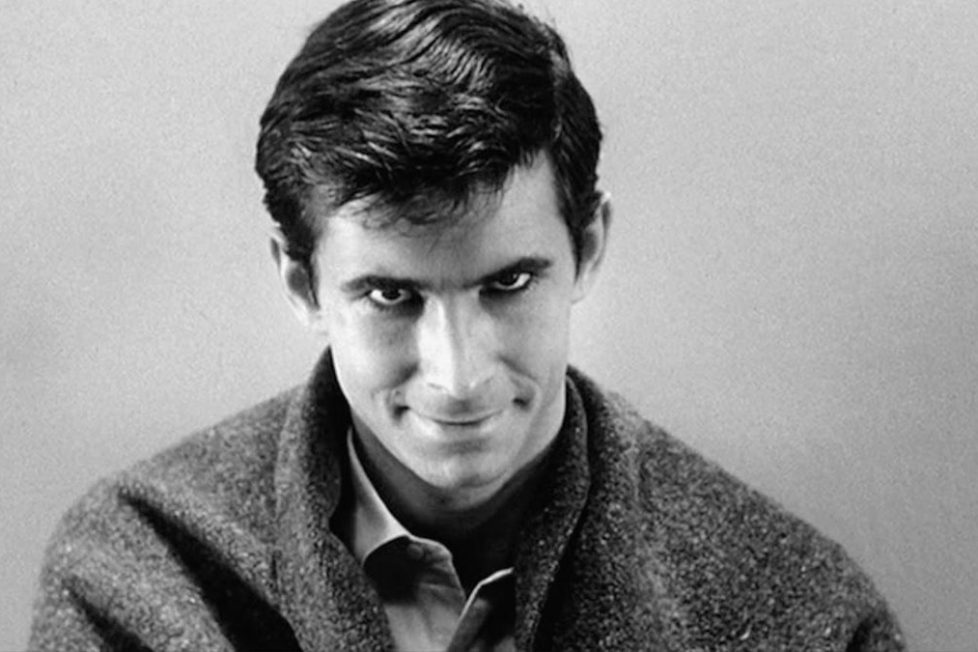

Here one of Hitchcock’s most brilliant decisions in Psycho comes to the fore: the casting of Perkins, creating a character so different from the Norman Bates in Robert Bloch’s 1959 novel. For much of Psycho, Hitchcock closely follows Bloch’s story, and though the director is sometimes credited with the masterstroke of killing Marion so early, that was all the novelist’s doing.

However, Bloch’s Norman was middle-aged and unprepossessing (like Wisconsin serial killer Ed Gein, unmasked a few years earlier, on whom he loosely based his story). The Norman of Hitchcock and screenwriter Joseph Stefano, contrastingly, is young and handsome in a boyish way; his pleasantness underlined by Perkins’s pre-Psycho image as a Hollywood heartthrob. This, and the way that both Marion and the audience sympathise with Norman’s complaints about his difficult mother up in the house, makes the movie’s ending all the more shocking.

That famous ending, where Lila comes face-to-face with Norman’s mother, is another indelible scene. Before then, we have continued (almost against our will) to empathise with Norman as he disposes of Marion’s car in the swamp and endures the taunts of his pitiless mother. And we have witnessed, as well, the standout sequence that almost matches the shower murder: the stabbing of Arbogast on the staircase in the Bates house, a scene that was in many ways as complex to film, partly because obscuring the face of Norman’s mother required such a high camera angle.

It’s testimony to Hitchcock’s skill in giving the second half of Psycho, at least, such an air of bloody dread that we barely register there are only these two killings in the entire movie.

All this is presented with an extraordinary economy in both word and image. As Hitchcock said, there’s “nothing about [Psycho] to distract from the telling of the tale, just like in the old days”, and the rather tagged-on psychological “explanation” at the very close is clearly only there to satisfy the literal members of the audience as well as the censors. (Unsurprisingly, they baulked at aspects of Psycho, and one of the most famous consequences is the skilful editing of the shower scene: far more nudity and violence is implied than is actually shown.)

In the main body of Psycho, then, there are no sophisticated subtexts or hidden meanings to be teased out, just the horror of what happens. To quote the director from his interview with Truffaut again:

My main satisfaction is that the film had an effect on the audiences, and I consider that very important. I don’t care about the subject matter. I don’t care about the acting. But I do care about the pieces of film and the photography and the soundtrack and all of the technical ingredients that made the audience scream.

That Psycho succeeds in this so powerfully is, at least to some extent, the happy result of unhappy attitudes toward the idea of a Psycho adaptation. When the film was first conceived in 1959, Hitchcock was at the height of his celebrity, and Psycho didn’t seem an obvious project for him—quite unlike, for example, that same year’s well-received and modestly successful North by Northwest, with its glitzy locations, a generous injection of humour, and glamorous Cary Grant as the lead.

Psycho appeared a grim and tawdry project, in comparison, built around dark madness and strong hints of what would then have been called sexual perversion. Paramount Pictures refused to back it and Hitchcock had to put up the money himself, reducing the budget to around $800,000 (only 20% of what had been spent on North by Northwest).

The decision to film in black-and-white came from this belt-tightening, as did the short shooting schedule and the use of a TV crew which the director recruited from the Alfred Hitchcock Presents series he’d been fronting. Hitchcock pared back the complexity of characters (especially Sam and Lila), made scenes simpler, and dropped some plans for intricate visual symbolism. And so Psycho became almost indie by the normally extravagant standards of Hitchcock, something much more akin to his quasi-documentary The Wrong Man (1956) than it was to big productions like Vertigo (1958) or To Catch a Thief (1955).

There were precedents for “name” directors slumming it in this way. Orson Welles had done much the same with Touch of Evil (1958), coincidentally also featuring Janet Leigh attacked in a motel; and Howard Hawks may have directed The Thing from Another World (1951) despite not having the credit. For Psycho, it was the best thing that could’ve possibly happened: something Hitchcock seems to have realised, for his next feature, The Birds (1963), had a similarly stripped-down feel in spite of having a larger budget.

The emphasis necessitated by the low-budget on just telling the story of Psycho efficiently was suited to Hitch’s primarily visual style, developed in the days of silent cinema, and made the one-dimensionality of many characters (again typical of Hitchcock, who was more interested in them as cogs in a plot than as people) less blatant than it in a production like North by Northwest, where few roles really ring true.

Audiences loved it, maybe ready now for a darker kind of American movie to match European films like Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Les Diabolique (1955), which Hitchcock had been aware threatened to topple him from his throne as the ‘Master of Suspense’. Although many found it funny as well as shocking, a response that’s difficult to understand given that there’s little obvious humour in Psycho, most responded exactly as Hitchcock had hoped to the suspense and the jumps.

This was enhanced, too, by the showmanship with which he surrounded both the production itself and the eventual release. While Psycho was being filmed, Hitchcock had repeatedly dropped teasers about the part of Norman’s mother—claiming, for example, that he was considering casting Helen Hayes in the role. (‘Mother’ was in fact played and voiced by several performers, both male and female.)

Then, when it reached cinemas, Hitch insisted that no latecomers would be admitted despite the then-common practice of running movies continuously so that people could enter and leave at any point. With an eye to publicity, he even suggested that cinemas post guards at the entrances. Starting to watch a movie at the beginning became, of course, the norm—even if the guards didn’t.

Psycho became the second biggest hit of the year in the US (bracketed by the decidedly different Swiss Family Robinson and Spartacus) and was blamed for a rise in crime. Hitchcock and Leigh were both nominated for Academy Awards, along with cinematographer John L. Russell and the art-direction team, although none of them won.

The failure of the Academy to even nominate Herrmann’s score seems unfathomable in retrospect. It’s now considered as much a masterpiece as, say, John Williams’ Jaws theme (a film that resembles Psycho in several ways, not least its focus on the story above all, and its shock early killing of a woman). Also unrecognised at the time, though now clearly essential to the film, was the graphic designer Saul Bass. Credited only for the titles and as a “pictorial consultant”, he also storyboarded the shower scene and other parts of the movie for Hitchcock, who liked every shot and nuance worked out in detail before shooting began.

Psycho’s legacy was considerable. There would be three direct sequels, none of them connected with the separate sequels that Bloch wrote to his novel, as well as related products like the biopic Hitchcock (2012), telling the story of Psycho’s creation with Anthony Hopkins playing Hitch. Then there’s the documentary 78/52: Hitchcock’s Shower Scene (2017) and the A&E TV series Bates Motel, which was a prequel to the Psycho narrative set in modern times. The 1960 movie is also often regarded as a forerunner of the slasher genre, though that view may be excessively focused on the shower scene itself. Unlike in most slasher movies, the killer in Psycho is at least partly sympathetic, and from their own perspective acting entirely defensively.

Then, of course, there’s the Bates house itself (arguably the third big star of the film along with Norman and his mother), which is still seen by thousands of visitors on the Universal Studios tour in Los Angeles.

The most remarkable descendant of Psycho, however, is Gus van Sant’s 1998 version (with Vince Vaughn as Norman, Anne Heche as Marion, and William H. Macy—who else?—as Arbogast). It’s not so much a remake as a replica, being almost line-for-line and shot-for-shot identical to Hitchcock’s version, and even reusing Herrmann’s score. Dismissed by some as a pointless exercise, the Psycho ’98 nevertheless succeeds precisely because we know at every moment exactly what’s coming. The sense of foreboding, of some homicidal ritual being enacted, is overwhelming. As Martin Scorsese said of Hitchcock’s shower scene, “it’s like a dream, and yet you’re still awake.”

And that is, surely, the fundamental power of Psycho. Certainly, some of its resonance comes from its demolition of comfortable 1950s values: trust, maternity, cleanliness, privacy, even stardom. But above all, it is a nightmare, where nothing goes right even at the moment when it seems to Marion and the audience that it just might be possible to put everything right. As Norman Bates says to her, “I think we’re all in our private traps, clamped in them, and none of us can ever get out.”

USA | 1960 | 109 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

director: Alfred Hitchcock.

writer: Joseph Stefano (based on the novel by Robert Bloch).

starring: Anthony Perkins, Vera Miles, John Gavin, Martin Balsam, John McIntire & Janet Leigh.