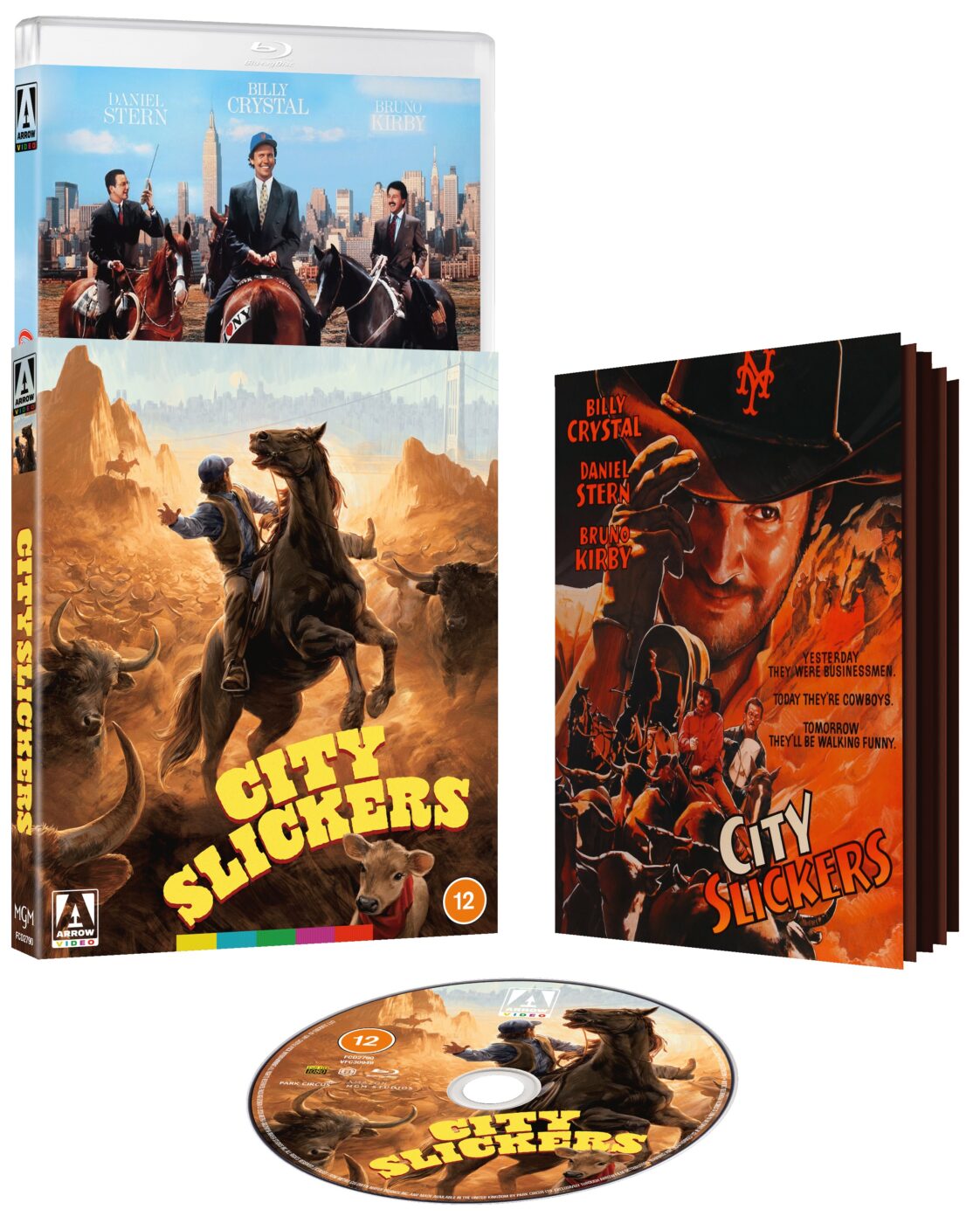

CITY SLICKERS (1991)

On the verge of turning 40, an unhappy Manhattan yuppie is roped into joining his two friends on a cattle drive in the southwest.

On the verge of turning 40, an unhappy Manhattan yuppie is roped into joining his two friends on a cattle drive in the southwest.

Stories first encountered during our formative years often take on new identities when revisited as adults. What once registered as harmless entertainment frequently conceals preoccupations and anxieties inaccessible to younger viewers. As audiences mature and their sympathies inevitably shift away from spectacle and towards character, they begin to gravitate towards the motivations and vulnerabilities that drive the narrative. Themes that seem nebulous and unimportant to children begin to acquire an uncomfortable clarity for those who’ve accumulated responsibilities and regrets.

Mainstream cinema has frequently smuggled such concerns into our consciousness under the guise of comedy. Steven Spielberg’s Hook (1991) is often considered a swashbuckling adventure; yet, beneath its fantastical exuberance lies a cautionary tale about emotional absence when consumed by professional responsibilities. Similarly, Mrs Doubtfire (1993) disguises a distressing portrait of familial fracture and childhood instability with a comic exterior. Ron Underwood’s City Slickers belongs to this lineage of ostensibly lightweight comedies. Though framed as a lighthearted Western escapade, it gradually emerges as a surprisingly reflective exploration of middle-aged masculinity, the fragility of male friendship, and the dawning awareness of mortality.

As Mitch Robbins (Billy Crystal) approaches his 40th birthday, he struggles to find purpose in the life he’s meticulously built for himself and his wife, Barbara (Patricia Wettig). His two lifelong friends are also experiencing varying degrees of existential dread. Phil (Daniel Stern) hides behind the success of managing a supermarket while suffocating in an emotionless marriage, whereas Ed’s (Bruno Kirby) adolescent impulsiveness masks a fear of genuine responsibility. In a desperate bid to change their routines, Phil and Ed organise a cattle drive through New Mexico for Mitch’s birthday. When Barbara quietly recognises her husband’s growing despair, the three companions decide to abandon the controlled chaos of New York City for the vast landscape of the American West. However, what begins as an escapist fantasy quickly becomes something far more sobering when tragedy strikes the chief cattle wrangler. As Mitch, Phil, and Ed confront the existential anxieties of mortality, they must also face environmental challenges while guiding the herd to safety.

At the absolute height of his popularity, Billy Crystal showcases his idiosyncratic brand of manic verbosity and neurotic charm as Mitch Robbins. While channelling a similar cynicism to that which made him such a recognisable presence in Rob Reiner’s When Harry Met Sally… (1989), the actor also imbues the disenchanted New Yorker with a vulnerability caught in an existential crisis. His humour functions as a coping mechanism that masks a genuine fear of mortality and irrelevance. Whether it’s the sarcastic quips fired towards his friends or the brittle repartee shared with his wife, Mitch uses levity to avoid confronting uncomfortable truths. It’s a delicate balancing act not many comics could achieve, but Crystal’s ability to balance humour with flashes of vulnerability allows the character to feel oddly relatable.

Opposite him, Daniel Stern delivers a finely calibrated performance as Phil. Having previously demonstrated a flair for broad physical comedy in Home Alone (1990), the actor deliberately suppresses those impulses here. While leaning into his vulnerability, he portrays a man perpetually on the brink of emotional collapse with moments of genuine pathos. Similarly, the late Bruno Kirby (Good Morning, Vietnam) proves himself extremely adept at comedy while maintaining a serious underside. As Ed, he embraces the character’s bravado and impulsiveness with infectious confidence. Yet, beneath his masculine exterior lies an undercurrent of insecurity that subtly exposes his resistance to maturity. Finally, the legendary Jack Palance (Shane) delivers an Academy Award-winning performance as the indomitable trail boss, Curly. His embodiment of a mythical figure of the Old West is played with finesse, serving as a perfect foil for these “city slickers”. He’s both intimidating and oddly philosophical, simultaneously capable of lighting a match off his own cheek while imparting wisdom.

What becomes striking when revisiting City Slickers with the quiet burden of obsolescence looming in the shadows is how it feels like a coming-of-age tale for a generation edging towards middle age. Much like they accomplished with Parenthood (1989), Lowell Ganz and Babaloo Mandel’s screenplay initially presents itself as a genial Western adventure. However, as the narrative progresses, it functions less as escapist fantasy and more as a vehicle for introspection. Beneath the situational comedy and broad character types lies a pertinent meditation on mortality and rediscovering life’s simple pleasures. This thematic core is most clearly expressed during Mitch’s nocturnal detour with Curly to retrieve stray cattle. In a brief exchange, the mythical wrangler cryptically reveals the secret of life is “just one thing”. When Mitch questions what that is, Curly replies: “That’s what you’ve got to figure out.” Delivered with deceptive simplicity, the moment functions as the film’s philosophical backbone. The single and essential purpose that gives life meaning will look different for each person, but the idea remains universal. Fulfilment and happiness don’t arise from escapist reinvention or performative adventure, but from identifying what gives one’s life coherence and holding onto it.

Curly’s presence functions as a nostalgic invocation of the Western archetype but also allows the screenplay to interrogate the mythology of traditional masculinity itself. Much like the cowboys Hollywood has idolised since John Ford’s Stagecoach (1939), Curly embodies every stereotype of Western manliness. He speaks in monosyllabic aphorisms, tolerates no emotional excess, and measures worth through endurance. When an awestruck Mitch first encounters the cattle wrangler, he proclaims: “Did you see that guy? That’s the toughest man I’ve ever seen in my life.” Yet, City Slickers refuses to romanticise his outward machismo without interrogation. Curly’s ideal of masculinity reveals itself as a liability rather than a virtue.

The cattle drive exposes the fragility beneath his hardened veneer, and it quickly becomes clear that his rejection of interdependence, vulnerability, and self-examination ultimately becomes his undoing. Instead, the film reconfigures masculine identity through a contemporary lens. As Mitch and his companions commandeer the herd, their eventual transformation isn’t marked by mastery over nature or dominance over others; rather, it’s defined by mutual support and an acceptance of uncertainty. Their growth suggests that masculinity should be recalibrated to accommodate responsibility, emotional articulation, and connection to others. It’s precisely this nuanced negotiation between past and present masculine ideals that elevates City Slickers above the disposable comedies of its era.

Considering its preoccupation with existential dread and masculine anxiety, it might be reasonable to expect City Slickers to collapse under the weight of its own melancholy. However, director Ron Underwood (Tremors) demonstrates a confident command of tone, ensuring the emotional seriousness never completely eclipses the broad comedy. Much of the humour derives from the juxtaposition of placing three physically unprepared and culturally disconnected friends into the Western environment they romanticise. Their attempts to appear rugged are consistently undermined by their incompetence. Whether it’s Ed’s forlorn attempt to channel John Wayne with a “Yahoo” or Mitch inadvertently causing a stampede with his portable coffee grinder, many moments generate genuine chuckles. Admittedly, it’s undeniably a product of its era, and some of the gags have inevitably aged poorly. A particular routine about the difficulty of programming a VCR will likely mystify contemporary viewers raised on streaming algorithms. Thankfully, these minor misfires are ultimately forgivable due to the unexpected measure of benevolence coursing through the 110-minute runtime.

Despite its considerable charms, City Slickers isn’t without its imperfections. The screenplay often leans heavily on familiar stereotypes, particularly in its treatment of gender. The female characters remain somewhat underdeveloped and exist largely to support the male protagonists’ emotional arcs. While these shortcomings are difficult to ignore when viewed through a contemporary lens, such missteps are emblematic of the cultural blind spots that defined the decade. Nevertheless, it emerged as an unexpected commercial triumph. Released during the summer when James Cameron’s Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) and Kevin Reynolds’ Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991) were preordained to rule the box office, City Slickers defied all expectations. It proved a quiet success, grossing an impressive $179Mm against a comparatively modest $26M budget. That success inevitably spawned City Slickers II: The Legend of Curly’s Gold (1994), a sequel that arrived to widespread indifference and failed to recapture the original’s charm.

Regardless, City Slickers continues to endure three decades after its release because it articulates a universal anxiety. The inescapable awareness of mortality and the increasingly desperate search for meaning in life transcends generational boundaries. By combining comedy with genuine moments of introspection, it reminds audiences that while life may feel overwhelming and repetitive, clarity can sometimes be found by remembering what truly matters. In an era saturated with interchangeable comedies, City Slickers manages to leave its audience with something to contemplate once the laughter subsides.

USA | 1991 | 113 MINUTES | 1:85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

Making its UK debut, City Slickers has received an exceptional restoration courtesy of Arrow Video. Sourced from the original 2K digital intermediate data, the 1080p transfer is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1.

The most notable improvement in this brand-new transfer is the enhanced richness of the colour palette. Although this release doesn’t benefit from a Dolby Vision High Dynamic Range (HDR) upgrade, primary colours are confidently amplified without appearing overblown. Academy Award-winning cinematographer Dean Semler (Waterworld) authentically captures the weathered ochres of the New Mexican terrain and the piercing clarity of the Colorado skies. Elsewhere, environmental greens burst with vitality, and the sunset’s graduated oranges glow with striking luminosity.

The presentation retains an organic, beautiful filmic texture that might initially strike the casual viewer as soft. However, upon closer inspection, the image boasts commendable sharpness that allows fine delineation to emerge, revealing rich details that haven’t been artificially sharpened or digitally processed. Viewers will appreciate the transfer’s ability to showcase intricate clothing patterns, the rugged texture of rocks, and Curly’s leathery visage with clarity. Black levels remain satisfyingly deep and stable, preserving an unobtrusive veneer of grain from start to finish, while flesh tones look naturalistic throughout.

This new release of City Slickers features a single English DTS-HD 5.1 Master Audio track, accompanied by optional English subtitles.

The audio boasts excellent fidelity and dynamism, clearly prioritising dialogue at the front to allow the surrounding channels to handle atmospherics. The mix excels during the opening stampede sequence, where the bass deploys a robust rumble as the cattle thunder past the listener. Meanwhile, the panicked cries of fleeing townspeople provide some genuinely impressive surround activity that sweeps across the soundstage.

Elsewhere, ambient sounds such as raindrops and hoofbeats are subtly threaded through the side channels. Perhaps the biggest beneficiary of this presentation is Marc Shaiman’s (Mary Poppins Returns) stirring score. It sounds precise and reverberates across the soundstage with newfound clarity. The surprising mid-range dynamics envelop the listener in warm orchestral textures, while the lower frequencies remain grounded. Admittedly, the track rarely erupts into a massive sonic spectacle, but this is likely the best City Slickers has ever sounded in a home environment.

director: Ron Underwood.

writers: Lowell Ganz & Babaloo Mandel.

starring: Billy Crystal, Daniel Stern, Bruno Kirby, Jack Palance, Patricia Wettig, Helen Slater, Josh Mostel & David Paymer.