STAGECOACH (1939)

A group of people traveling on a stagecoach find their journey complicated by the threat of Geronimo and learn something about each other in the process.

A group of people traveling on a stagecoach find their journey complicated by the threat of Geronimo and learn something about each other in the process.

It’s June, 1880. A group of eight people pile into a stagecoach travelling from Tonto, Arizona Territory, to Lordsburg, New Mexico. However, they are heading across perilous terrain—Geronimo and his legions of Apaches wait ominously on the horizon. If these eight strangers are to make it across the desert in one piece, they’ll need to rely on each other.

John Ford’s Stagecoach has been credited with revitalising the Western genre. Perhaps even more impressively, it’s also been acclaimed as one of the best films ever made. While I wouldn’t herald the work as highly as that, it’s easy to see why this film represents a significant milestone in cinema history. With vast, sweeping shots of Monument Valley, Ford forges a new era in American filmmaking by creating a story steeped in themes of prejudice, race, justice, and myth.

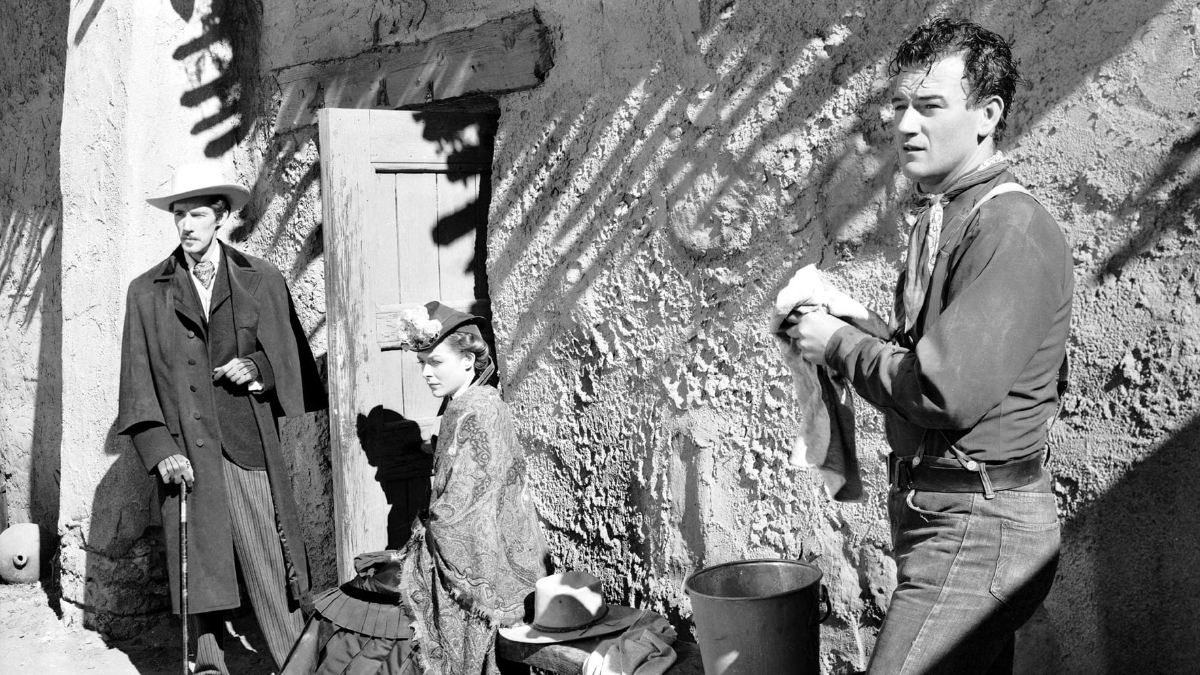

Of course, Ford could never have achieved it without his star: John Wayne. Determined to turn his friend, then an unsuccessful actor, into a household name, Ford created one of the best character introductions in all of cinema.

As the stagecoach hurtles around a corner at breakneck speed, a man stands in the clearing, holding a rifle. Ford zooms in on the now iconic visage of ‘Duke’ as he smiles broadly, squinting in the bright Arizona sun. If there was ever a way to turn someone into a star, it is with an introduction like this.

Wayne’s performance—for which he was only paid a meagre $3,000, a fifth of what his co-star Claire Trevor made—set the standard for his showings for years to come. He is the embodiment of tough, laconic, American Frontier justice, the physical manifestation of traditional masculinity. As a sunburnt, dust-covered cowhand, he’s on his own mission for vengeance that exists outside of the main plot—killing the men who slaughtered his father and brother.

“There are some things a man simply cannot run away from,” he intones, somewhat mournfully. Although he desires to elope with his new love, he understands that his quest will never be over until vengeance is achieved. Interestingly, his portrayal never descends into the grim, hate-filled, and bloodthirsty portrayal of Ethan Edwards in The Searchers (1956). Instead, Wayne, as the Ringo Kid, is unusually empathetic, at least when compared against some of Wayne’s other offerings, which are decidedly stern.

The first formal detail you’ll notice when rewatching this classic film is the aspect ratio; the framing feels peculiarly small. At 1.37:1, it seems rather square for a Western epic. Perhaps, having seen so many Westerns depict the Wild West on sprawling 70mm film stock, it feels strange to see the American Frontier in such a blocky format. For reference, Ford’s The Searchers—his most celebrated Western, if not his best film overall—has an aspect ratio of 1.85:1. Meanwhile, the quintessential Western, Sergio Leone’s masterpiece The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1968), boasts the superbly immersive 2.35:1 format, which has since become synonymous with the Western epic.

Showing a film in widescreen wasn’t as easy in the 1930s, which may well explain John Ford’s standard framing choices. Although 70mm film had already been established—even being used in John Wayne’s first leading role in The Big Trail (1930)—it was financially unsustainable as most cinemas weren’t equipped for widescreen. This was the primary reason why Wayne’s performance in The Big Trail went relatively unnoticed—few audiences had the opportunity to see it.

However, other formal aspects of the film still impress. The lighting and cinematography in some scenes are particularly beautiful. As Wayne courts Trevor under the moonlight, solemnly asking for her hand in marriage, one can’t help but feel a little spellbound. Cinematographer Bert Glennon masterfully depicts the lovers, both outcasts and societal rejects, as a pair of lonely misfits with hearts of gold. As the evocative light falls upon their faces, we are left to wonder if such a world can foster love for people like them.

This sequence is among the best scenes in the film, although there are many more. Howard Hawks was once quoted as saying: “A great film has three good scenes and no bad ones.” This rather neatly summarises Stagecoach, although the film itself is not without fault. Featuring such standout interactions as this one, Wayne’s introduction, as well as the final showdown and grand finale, it’s no wonder that Stagecoach was ground-breaking for the time.

Perhaps the most mesmerising aspect of the film, especially for audiences 85 years ago, was the action sequences and innovative camera angles. In a climactic scene, the eight passengers of the Stagecoach are being chased by the Apaches, led by the infamous Geronimo. There’s a stunt that’s so impressive, given that it was all truly performed, that it will still make you gasp today. When stuntman Yakima Canutt asked John Ford if they had caught his stunt on film, Ford replied: “Even if we hadn’t, I’m never doing that again.” Fortunately, the stunt was captured and makes for some heart-pounding cinema, no matter what screen you’re watching it on.

Unfortunately, not everything in the film is successful. I generally dislike pointing out how certain classic films haven’t aged gracefully in terms of representation—it seems such an obvious observation that it almost doesn’t bear mentioning. In addition to this, many people seem to think that, if they can moralise on how a film made over half a century ago doesn’t share current standards of thinking, it detracts from the film’s aesthetic value.

While I would normally disagree with this, the portrayal of Apaches in Stagecoach is so tastelessly one-dimensional and utterly devoid of any nuance that it significantly detracts from the work, in my opinion. Although Ford’s film doesn’t reach the racist extremes of D.W Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (1915), the Apaches are only shown as a violent, disorganised force of aggression; not a single moment is given to contemplate why the indigenous population might be so angry.

For the longest time, we don’t see the Apaches at all, only the devastation and destruction they cause. This tone-deaf portrayal of Native Americans as the harbingers of unspeakable violence was a leitmotif that Ford would return to throughout his career, most notably in The Searchers. Both Wayne and Ford gave interviews where they spoke about such depictions later in life; however, rather than redressing these problematic portrayals, these conversations only served to exacerbate the issue.

Having said that, it’s foolish to dismiss the work outright. Ford’s film revitalised the Western as a genre, perhaps even because he indulges in such representations. The image of a stagecoach gallantly galloping across the desert, undeterred by the legions of Native Americans trying to stop them, is emblematic of the philosophy that defined the American Frontier: nothing can stop progress or expansion, no matter the cost.

Perhaps the greatest testament to Stagecoach’s influence is that I cannot think of a better Western film that predates it. It’s truly the greatest Western of its era and arguably remained so for another 17 years, until Ford himseld then made The Searchers.

Looking at how it’s influenced contemporary cinema, one need only look at two 2015 releases: Mad Max: Fury Road and The Hateful Eight, both of which bear striking similarities to Ford’s picture.

Whilst the film may not particularly reach any great heights, it remains consistently strong throughout its entire 97-minutes, hitting story beats in an exceptionally reliable way. In this respect, one can see how it arguably provides the template for how to make a stellar Western in the sound era, if not any film in any period. Indeed, Orson Welles is said to have watched Stagecoach more than 40 times in preparation for directing Citizen Kane (1941).

This becomes incredibly ironic when you recognise that Ford controversially beat Welles in award season when he won the Academy Award for ‘Best Picture’ and ‘Best Director’ for How Green Was My Valley (1941). Although Welles’s film is undoubtedly superior, the cinema of John Ford is so magnetic that it’s easy to forgive the mistake. The man truly knew how to make a film—if nothing else, his first great movie is evidence enough of that.

USA | 1939 | 97 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH • SPANISH • FRENCH

director: John Ford.

writer: Dudley Nichols (based on ‘The Stage to Lordsburg’ by Ernest Haycox).

starring: Claire Trevor, John Wayne, Andy Devine, John Carradine, Thomas Mitchell, Louise Platt, Donald Meek, George Bancroft, Tim Holt & Berton Churchill.