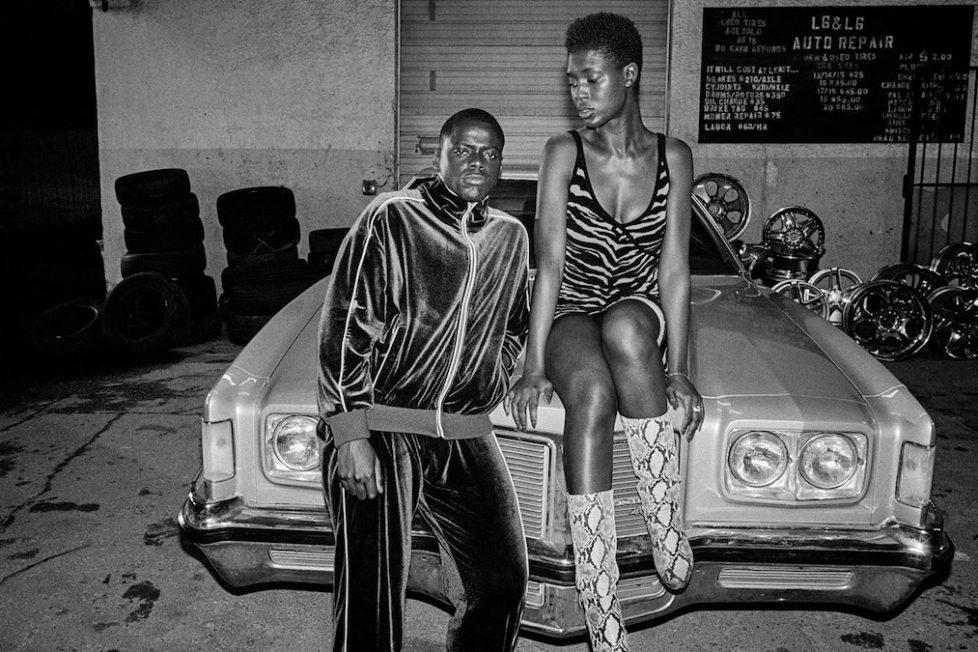

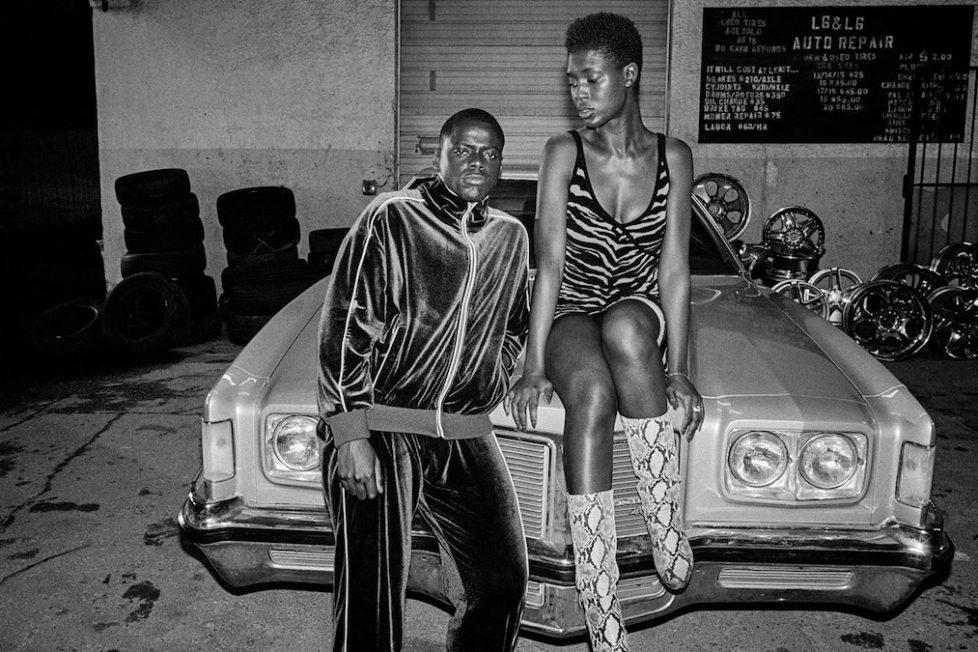

QUEEN & SLIM (2019)

A couple's first date takes an unexpected turn when a police officer pulls them over.

A couple's first date takes an unexpected turn when a police officer pulls them over.

At first glance, Queen & Slim looks like a straightforward black reworking of Thelma & Louise (1991). Two people are pursued cross-country after a shooting for which they can’t be entirely blamed, becoming lovers along the way. The shape of the film is dictated by their journey, other characters are people they meet on the way, and the overriding question is whether or not they’ll reach safety. Indeed, the climactic scene nods overtly to that Ridley Scott’s feminist classic.

But where Geena Davis’s Thelma and Susan Sarandon’s Louise were pretty much the only concerns of that 1991 hit, here much of the interest comes not from Queen (Jodie Turner-Smith) and Slim (Get Out’s Daniel Kaluuya), but from how others respond to them. The eponymous pair are likeable, even admirable—the movie’s human core. Their relationship is what it celebrates and we root for them… yet they never surprise us.

But through the minor characters, a tantalising picture is slowly drawn of the frenzy surrounding their case (in the media and on the streets) and the conflicting feelings it arouses. Slim’s shooting of a white cop who was probably going to shoot them (or was he?) excites condemnation and support, riots, and in the film’s most startling scene more shooting.

We’re hardly shown any of this directly, however—as we travel from Ohio to Florida with Queen and Slim we share their bubble of self-imposed seclusion and get only glimpses of the larger context.

Setting up such a sharp contrast between private lives and the wider world in this way is a brilliant tactic in a highly impressive film, all the more impressive because both its director, Melina Matsoukas, and its writer, Lena Waithe, are both making their feature debuts here. Although Waithe was memorable as an actor in Ready Player One (2018), and Matsoukas is noted for a music video.

Their balancing act works superbly. While constantly alluding to what’s going on elsewhere, and using that to add variety and unpredictability to the narrative, they also keep the humanity of Queen and Slim permanently in the foreground. Although the duo becomes a cause célèbre in the bitter debate about America’s policing of its black population, they’re never reduced to mere stand-ins for every African-American who’s been harassed by a cop.

And this refusal to let them be defined by their victimhood gives Queen & Slim an emotional richness that, say, Kathryn Bigelow’s Detroit (2017) or even Jordan Peele’s over-rated Get Out (2017) lacked.

It’s true that the leads themselves—despite being both sympathetic and plausible—can sometimes feel incompletely realised as characters, particularly Slim. His licence plate, for instance, reads “TrustGod” and yet the movie never examines a sense of religion or irony within him that might explain this choice.

Still, even if it’s frustrating that we don’t feel we get to know them better, both Turner-Smith and Kaluuya are convincing. They deftly convey almost imperceptible changes in their relationship, with Slim (who starts out as the less resolute of the two) gaining strength while the initially brittle Queen allows herself to become more vulnerable.

Queen & Slim is also often fresh and unexpected in the way it portrays other characters’ reactions to the fleeing pair. If it’s a little unimaginative to make the dead cop a proven racist and killer (the moral questions raised by Slim killing him would be more interesting if he’d been a good guy), for the most part, the people they encounter are as unpredictable and unstereotyped as in real life.

Another white cop (Sturgill Simpson, the country singer frequently referenced in Jim Jarmusch’s The Dead Don’t Die) turns out to be sympathetic and well-meaning. An auto mechanic knows what they’ve done, yet won’t hand them over to the police—but he doesn’t really approve either, and he’s happy to demand every last cent they have in payment for repairs to their car. His young son Junior (a striking Jahi Di’Allo Winston) naively idolises them as heroic freedom fighters and tries to emulate them with terrible results.

Queen’s Uncle Earl (Bokeem Woodbine) typifies the depth that Matsoukas and Waithe give to even fairly small parts. Again, he’s willing to help Slim and Queen, up to a point, but self-interested too. He’s jovial and bouncy on the surface, but ruthless underneath, and then genuinely concerned beneath that. Nobody here is a cypher.

A white couple who Queen and Slim visit for help, the Shepherds, are equally ambivalent—played by Flea (as convincingly dangerous as he was in Boy Erased) and a very fine Chloë Sevigny. The latter perhaps encapsulates both a common attitude and a common delusion in wishing that all this race stuff would just go away.

Waithe’s screenplay is smartly constructed, with dialogue that manages to communicate important background (such as the existence of the death penalty in Ohio) without seeming artificial, and some apparently aimless naturalistic chatter that gives us a good flavour of the characters. An irritable date in a diner that opens the film is a little masterpiece.

Just occasionally there’s some heavy-handed insertion of profundity, however—for example, when Queen says grace at the Shepherds’ dinner table and thanks God “for this journey—no matter where it ends”, or when both Junior and Slim at separate points contemplate the importance of leaving a personal legacy. But they’re few and far between, and certainly not enough to mar a script that steers clear of melodrama and lectures.

There are long sequences that never drag (the 12-minute pre-title sequence consists of just three scenes) and even occasional humour in a movie that is largely bittersweet. For instance, when Slim attempts to rob a gas station and the awestruck clerk simply wants to hold his gun. Slim eventually relents, which says everything about the way Kaluuya’s character still doesn’t grasp the gravity of his own situation. “I’m not a criminal”, Slim insisted earlier, when Queen reminded him “you’re a black man that killed a cop and took his gun.”

Perhaps most importantly, Queen & Slim gives time to the seemingly trivial. Even during their six-day flight from the police the pair still argue over petty things (like the noise Slim makes when he eats), underlining what may be the movie’s central point: they’re still people, not just criminals, not just pawns in racial conflict. They’re living actual lives and they have hopes, even when hope seems to be dwindling… and if it was their inadvertent crime that forced them together at first, before long they want and need to be together.

In this, Queen & Slim more than anything resembles Barry Jenkins’s If Beale Street Could Talk (2018), which similarly used a young black man’s prejudicial treatment by the police as a pretext to celebrate something much more positive—the flourishing of love in the most adverse circumstances. That contrast between the harsh broader picture and the tender personal one is, indeed, brought home here by one forceful sequence which culminates in a jaw-dropping edit.

Backing all this up is luscious, often gorgeously-coloured photography by Tad Radcliffe, and a strong original score by Devonté Hynes with interesting atmospheric uses of percussion. True, there’s just a hint of a Big Theme at the very end (where the epilogue as strays briefly into sentimentality) but it’s soon under assault by less melodic elements. With Hynes’s music complemented by some two dozen songs ranging from Duke Ellington to Lil Baby, through Fela Kuti, the soundtrack of Queen & Slim is as energetic and unhackneyed as the film itself.

The movie will, inevitably, be seen as making a social-political statement. And it is certainly not trying to gloss over the existence of systemic injustice, or for that matter individual selfishness, both of which are on ugly display here. But I suspect the statement that Queen & Slim really wants to make is that the bad news, in the headlines and on the TV and on the streets, is not all that matters: good things can still exist between individuals.

Just like Thelma & Louise, it’s sad… but far from bleak.

director: Melina Matsoukas.

writer: Lena Waithe (story by James Frey & Lena Waithe).

starring: Daniel Kaluuya, Jodie Turner-Smith, Bokeem Woodbine, Chloë Sevigny, Flea, Sturgill Simpson & Indya Moore.