WATCHER (2022)

A young woman in a strange city believes a man across the street is spying on her

A young woman in a strange city believes a man across the street is spying on her

Julia (Maika Monroe) and her partner Francis (Karl Glusman) are examining CCTV footage at the Bucharest supermarket where, Julia believes, she’s finally secured evidence that a man from their neighbourhood (Burn Gorman) is stalking her.

“He’s staring right at me,” she says. “Maybe,” says Francis. “Or… he’s staring at the woman who’s staring at him?”

Writer-director Chloe Okuno, making her feature debut, is unafraid to state this interpretative dilemma overtly, and it’s important she does so. While it’s possible to see Watcher superficially as a #MeToo film about an unbelieved and gaslit victim, it’s also about uncertainty. We sympathise with Julia’s disquiet about the man across the street but, at the same time, we have to recognise it is her who follows him through the city, and that his presence in the supermarket is unremarkable. She’s not in the wrong, but that doesn’t mean she’s exactly right.

And once the movie’s over, though Okuno cleverly leaves some things open-ended while giving the appearance of a definitive conclusion, other points may occur to us. Was he, perhaps, watching someone else all along? Was his wave to her really as sinister as it seemed at the time, given she waved to him first? Perhaps most importantly, who hasn’t idly spied on others for a few minutes, trying to figure out their lives from silent movements? After all, Julia describes it as merely “people watching.”

This isn’t to say Watcher is an anti-#MeToo movie. Far from it. Julia’s experience is real and scary, she’s not at fault for that, and there really is a monster prowling Bucharest. But Okuno’s film, released theatrically last year (when it also made my list of the best movies of 2022), encourages us to remember that not everything is as it seems and that views are shaped by our own expectations. Gorman’s character is so “obviously” peculiar, with his intense yet passive face and his fussily precise way of moving, that it’s all too easy to read him as threatening.

Julia’s partner Francis also runs the risk of becoming what we expect him to be: is he caring and calming, or uncaring and dismissive? Do his quick friendships with colleagues at his new company suggest a man losing interest in Julia, who maybe even is unfaithful, or are they just normal behaviour from which she—in an unfamiliar country where she doesn’t know the language—is temporarily excluded?

The storyline of Watcher (possibly not called The Watcher to avoid confusion with Netflix’s bizarre though intermittently fascinating TV series) is simple, and the premise even simpler. Julia and Francis have moved from the US to Romania for his job; he speaks Romanian and has roots in the country, but she doesn’t. Soon after their arrival, they walk past a crime scene, discovering afterwards that it involved a serial killer nicknamed ‘The Spider’.

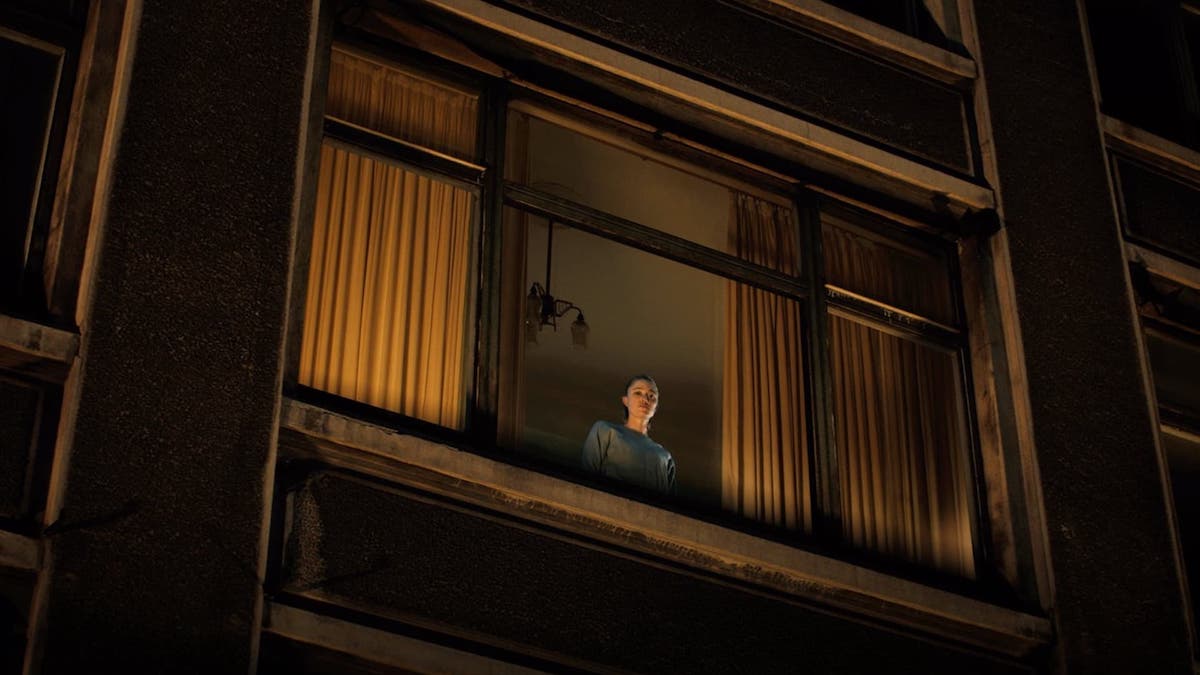

Julia notices a man in the apartment block opposite, slightly higher up than their home, who often seems to be gazing through his window at her. She becomes increasingly preoccupied with him, while he (seemingly) never stops staring.

Okuno’s film is far from uneventful and the pace never drags thanks to a screenplay that moves swiftly around different aspects of Julia’s life, while also dropping sly hints about later plot developments. For example a character’s comment about police incompetence, or her own plans for learning Romanian. There are even tiny drops of humour; when Julia goes to the cinema it’s to watch Charade (1963), about an American female ex-pat. But Watcher never digresses far from the anxiety at its heart.

There are some gripping sequences, notably one in the supermarket where we first see Gorman’s character clearly, and another where Irina finds herself stuck on a subway train with him. There are some impressively effective individual moments, too—for example, a scene where Julia opens the curtains and immediately sees her nemesis, apparently watching. The key to the film’s power, however, is its growing sense of paranoia.

Some of this comes, subtly, from the repetition of images related to windows, watching, and seeing. Julia is shown early on in a taxi driver’s mirror; we see her against the window as soon as she and Francis arrive in their apartment, and shortly afterwards see them both through it; there is glass in their bedroom door, a spyhole in the front door, a large window-like serving hatch from the kitchen. There are window-like decorative rectangles on the walls, Julia wears sunglasses, she watches a victim of The Spider on her laptop, and she’s even caught in the stairwell surreptitiously watching her neighbour Irina (Mădălina Anea).

Again, all of these things are normal when considered literally. But in the context of Watcher, they take on darker meanings.

The scope of Julia’s worries is extended from the visual to the aural, as well; partly when she hears worrying things through the walls, but also by Okuno in her decision not to subtitle the Romanian dialogue (extensive in a few scenes, though not the movie as a whole). Leaving a foreign language incomprehensible to most viewers is not a new idea—Carol Reed does it in The Third Man (1949) and Nicolas Roeg rather patchily in Don’t Look Now (1973), to cite just two examples—but it works perfectly here in the service of the story, accentuating Julia’s isolation. I don’t know if it was intentional, but Romanian is also ideal for this; few English-speakers will fully understand it, but it’s close enough to more familiar languages like French and Spanish that they may grasp the vaguest, tantalising—or discomfiting—outline of meaning.

Other than that, the Bucharest setting is largely incidental (a brief appearance by a Dracula statuette being the only self-aware nod to cliché). But the movie could be set almost anywhere and, as in most of the best paranoia films, Okuno plays things pretty straight with a clear, unflashy narrative and visual style that lets events and performances speak for themselves.

Much of Watcher is shot in half-light but this isn’t done for melodramatic effect; a lot is bright, too, and Julia and Francis’s apartment often looks like something out of an interior design magazine. Spaces can feel both claustrophobic and frighteningly exposed, but this is surely a result of our identification with Julia as much as any directorial emphasis. Nathan Halpern, meanwhile, contributes a fine eerie score that emerges at just the right moments with big rumbles or nervy buzzing.

Monroe—previously the target of a more fanciful stalker in It Follows (2014)—has by far the dominant role, and she balances Julia between nervousness and normality very successfully, growing progressively more uneasy as the film progresses but not moving straight to victimhood or entirely losing confidence. Even the secondary characters—Francis and the apparent voyeur—are minor by comparison. The latter is equally essential to the story, but only as a symbol. Good supporting performances are added by Anea as the neighbour Irina, Florina Ghimpu as a slightly sceptical police officer, and Cristina Deleanu as a cat lady whose lost pet Elvis, at first, seems like comic relief, but turns out to be pivotal in a later scene.

Comparisons to Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954) are inevitable, given the resemblance of the two movies’ starting points, but Watcher fits more naturally into the vast category of movies about lone women threatened by intruders. (That Julia is not actually alone, and the man does not enter her apartment, is a technicality; from her perspective, she might as well be, and he might as well do so.)

Where it differs from most, however, is that it leaves open the question of exactly how real the threat is, while not denying the reality of Julia’s experience. In this respect, it has some affinities with Gia Elliot’s interesting Take Back the Night (2021) and, in playing with our assumptions about women and men, victimhood and threats, it also recalls the first section of Zach Cregger’s Barbarian (2022).

Watcher suffers a little from an abrupt ending—it’s rare a movie would benefit from another 5-10 minutes, but this one probably would. That apart, though, Okuno’s film is a highly accomplished thriller, thoughtful but concise and compelling, blending the paranoia of urban isolation with more specific fears about women’s vulnerability, and asking questions that in their way are almost as disturbing as the face at the window.

UAE • USA • ROMANIA | 2022 | 91 MINUTES | 2.00:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • ROMANIAN

writer & director: Chloe Okuno.

starring: Maika Monroe, Karl Glusman & Burn Gorman.