A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET (1984)

The monstrous spirit of a slain child murderer seeks revenge by invading the dreams of teenagers whose parents were responsible for his untimely death.

The monstrous spirit of a slain child murderer seeks revenge by invading the dreams of teenagers whose parents were responsible for his untimely death.

Mysteries, incredible body hocus pocus, the truth is we still don’t know what [dreams] are or where they come from.—A Nightmare on Elm Street.

What a dream concept for horror: a killer who can only kill you while you’re asleep. It’s just surprising how such a fantastic idea would be so difficult to turn into a film. Trying to recollect a dream brings about all sorts of details that alter the feeling you had when you first awoke. I discovered new details with this latest rewatch of ’80s classic A Nightmare on Elm Street, refreshing my appreciation for how writer-director Wes Craven (The Last House on the Left) shaped such big ideas into a taut and confident slasher film.

A Nightmare on Elm Street follows teenager Nancy (Heather Langenkamp) and her friends as they try to evade Freddy Krueger (Robert Englund), a dead child-killer immolated by their parents long ago, who’s back from beyond the grave and looking for revenge in their dreams.

In 1981, Wes Caven’s script for A Nightmare on Elm Street was rejected by several film studios. Disney wanted to tone it down for children, understandably, while Paramount passed because they were developing a similar idea that became Dreamscape (1984). The pitch was becoming Craven’s waking nightmare between a divorce, financial ruin, and trying to keep working after Swamp Thing (1982) flopped.

Craven ‘found’ Freddy in a news article from the 1970s about Southeast Asian refugees suffering intense night terrors that caused them to die in their sleep. As a child himself, Craven vividly recalled an elderly derelict in a ragged hat and jumper who spotted him through his window, then began to walk backwards with eyes fixed on him.

No wonder Craven would return to the by-then-heavily-commercialised Freddy Krueger with New Nightmare (1994), revitalising him with the concept of a true ancient evil possessing a horror icon to gain enough strength to kill again. How else did the original Freddy come to existence but as an abstract terror taking form through a lifetime of unconscious trauma? Both Craven and his teen characters never learnt of the man before dreaming about him, but he emerged nevertheless.

Finally, things took shape as Craven not only found a studio willing to produce his movie. New Line Cinema is today more synonymous with The Lord of the Rings trilogy, but at one point they couldn’t even pay the cast and crew making Elm Street. A $700,000 budget that swelled to over $1M would have devastated them if it wasn’t a hit, but thankfully it grossed over $25M during its US release alone. New Line may have been the house Gandalf renovated but it was first built by Freddy.

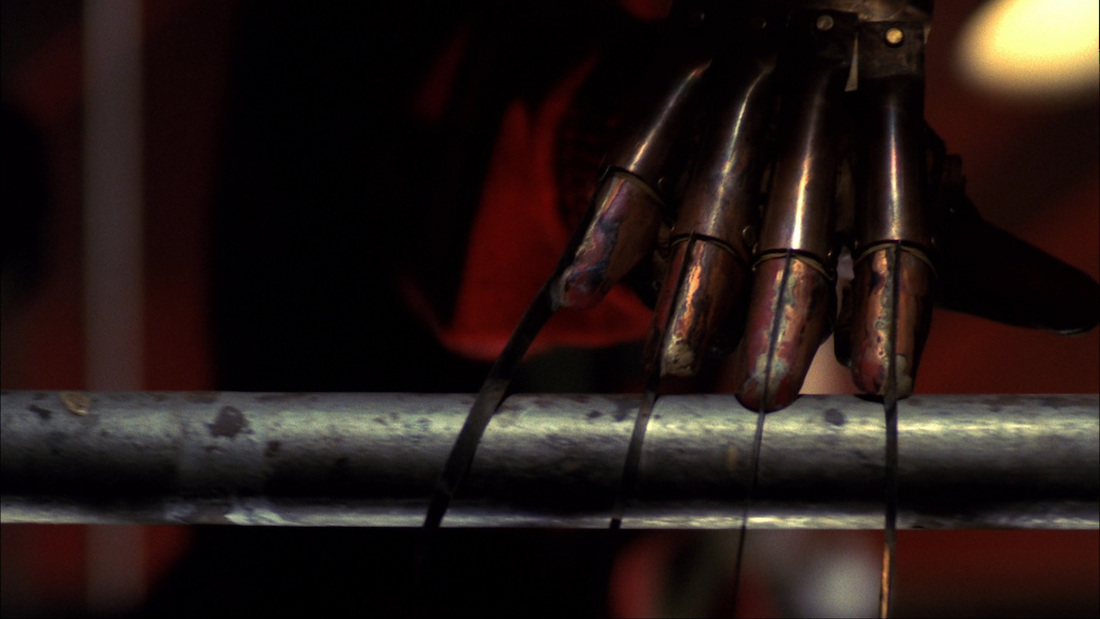

I’ve seen this movie many times; alone as a child, with friends, and while listening to the rap album Freddy’s Greatest Hits trying to absorb the experience afresh. When a sadistic killer now comes with his own board game it can be hard to separate the source material from the cultural zeitgeist (a phenomenon Craven would respond to with 1989’s Shocker). But when the original Elm Street starts with those grubby hands constructing his iconic bladed glove—the weapon of a modern “predatory animal” as Craven described it—you immediately feel alone with Tina (Amanda Wyss) down in that hellish basement.

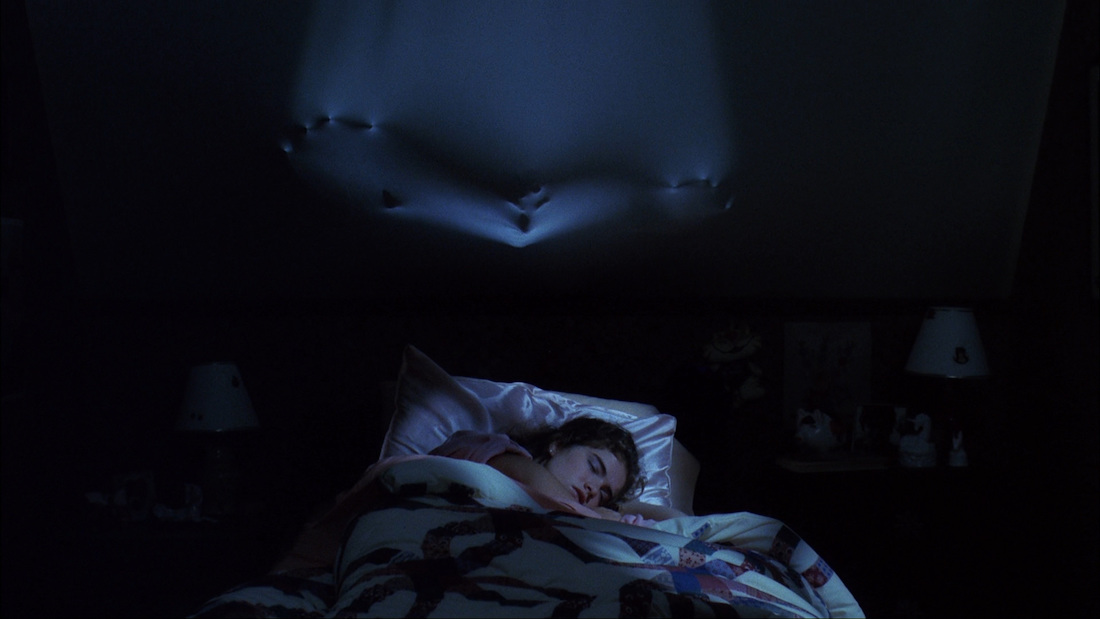

There’s a slickness to the story and pacing of A Nightmare on Elm Street. Avoiding the stop-and-start nature of earlier slashers like Halloween (1978), where we followed teenagers oblivious to a killer stalking them, here the would-be victims are constantly haunted by Freddy. Craven’s friend and colleague Sean Cunningham directed Friday The 13th (1980), which contained long sequences of drab teenage dialogue as Jason Voorhees lurked in the background, whereas here daylight sequences are a rarity. It moves from one night to the next, underscoring the fact that these teens cannot escape Freddy’s threat. Tina survives one night only for another to arrive, where even the company of her best friends, Nancy and Glenn (Johnny Depp), together with her boyfriend Rod (Jsu Garcia), prove helpless against her nightmares.

Teenagers die at the start of Friday The 13th to keep butts in seats. And in many slasher films, the first victim never gets found because they’re not actually that important. Tina’s gruesome death being dragged around her own bedroom by an ‘invisible attacker’, is as entrancing as it is terrifying. It’s an inexplicable spectacle that drives the story and characters forward with the clear message something otherworldly is coming for them. Pushing past the conventions of sex equals death where killers deliver swift ‘justice’, Freddy draws out his kills with sick pleasure. Tina’s bloodied contortions and agonised screams leave a lasting impression, in an uncomfortable sequence that’s a technical marvel for the time.

The evocation of rape is no mistake, either. Englund and Craven co-created a disturbing boogieman who relished in his own ‘pure evil’. Craven has said Freddy “stands for the worst of parenthood and adulthood—the dirty old man, the nasty father and the adult who wants children to die rather than prosper.” His truest repugnancy of being a child molester was only scrapped to avoid being considered exploitative of several publicised Californian sexual assaults at the time.

One can avoid The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’s (1974) Leatherface by not going to Texas, but Elm Street provides a commentary on ‘normal’ Americans who try to drink or boss away their problems. People who never acknowledge that the barring of windows won’t matter if the threat comes from within the home, or one’s own mind.

Nancy learns the only way to defeat a phantasm like Freddy is to turn her back and take away the power she gave him through fear. Craven never got the chance to do the same. New Line forced his hand with a sequel-baiting twist-ending that helped spawn a lucrative nine-film franchise, including a ridiculous grudge match against Jason Voorhees in 2003 and an unimaginative remake in 2010. Each entry one-upped the last one in terms of theatrics, forgetting where the horror worked in fantastical deaths like Tina’s and Glenn’s.

While the big-budget surrealism was entertaining it was never as scary as the original. What scared me most this time was how subtle the blurring of dreams and reality is; while the image of Freddy tonguing Nancy through the phone stuck with many, what’s so effective is how the scene transitions right to her talking to her mother. Where does the nightmare begin and end? By the time Nancy decides to fight back the entire night is indecipherable in what really happens.

Planning for the future can be as hazy as recollecting the past. Nancy’s hair greys and, as she looks at her reflection, she opines “I look 20 years old”—as if reaching that age is as magical as Freddy himself.

Teenagers don’t have a true grasp of time. They don’t imagine the long-term debts or number of times they’ll move house, so they dream ahead to a fixed point where they expect life to make sense. People overlook that Wes Craven was an academic and infused a lot of his teachings into his movies. He didn’t just know that nightmares coming true would be scary, but that by invading the minds of kids cuts off their futures. To Craven, being awake or asleep was never a binary in A Nightmare on Elm Street; he equated it to Russian philosophy stating there are different levels of consciousness and “to know what’s true is painful.”

Nancy never had to discover a way to beat Freddy Krueger… she had to come to terms with the terrible crime her parents committed out of love and learn to forgive them.

writer & director: Wes Craven.

starring: John Saxon, Ronee Blakley, Heather Langenkamp, Amanda Wyss, Nick Corri, Johnny Depp & Robert Englund.