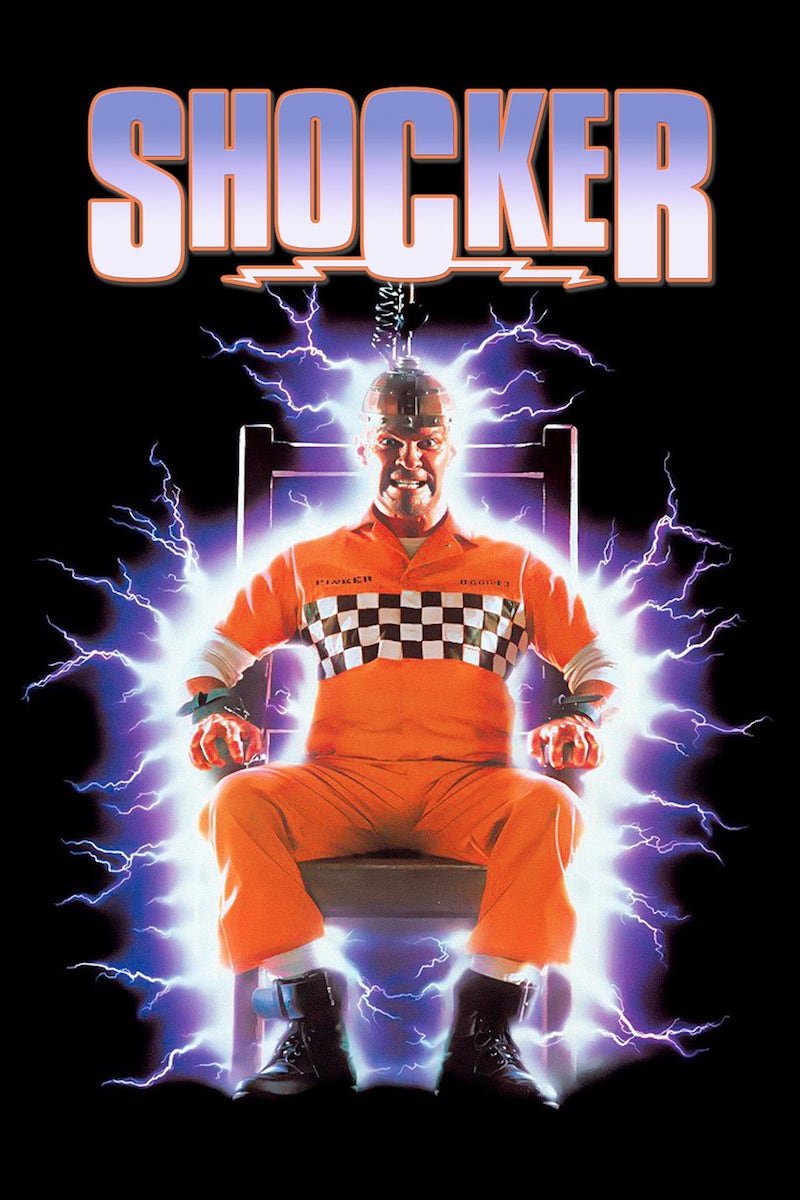

SHOCKER (1989)

After being sent to the electric chair, a serial killer uses electricity to come back from the dead and carry out his vengeance on the football player who turned him in to the police.

After being sent to the electric chair, a serial killer uses electricity to come back from the dead and carry out his vengeance on the football player who turned him in to the police.

Wes Craven’s Shocker is the most divisive of his many horror offerings. It didn’t cause much of a stir at the box office and reviews at the time were mixed, to say the least. I confess right away, I love this film more than you hate it and would place it up there with late-1980s classics that share its cyberpunk sentiments like RoboCop (1987), The Hidden (1987), and especially John Carpenter’s They Live (1989), which shares its theme of manipulation through mass media. These films also have a punk flippancy in common that helps make them fun whilst attacking some serious subjects.

They Live and Shocker were both made with Alive Films, a short-lived production company founded on a novel idea that should be commonplace. It was the brainchild of film producer and music industry maverick Shep Gordon, who believed that filmmakers should be given creative freedom with no intervention from studio or distributor during either development or production. With guaranteed pre-sales via the home video market, he could ensure the comparatively low budgets he offered would be recouped. Anyone of the right age who remembers renting or buying movies released on the Embassy Home Video label can feel smug now, knowing they helped to finance these films!

The only contractual clause that Gordon insisted on was that a cult director’s name appeared above the title on all marketing. All creative decisions were then left in the hands of that director. Alive Films didn’t even ask for script or casting approval. The model was so successful that it soon attracted the attention of big distributors including Universal, Carolco, and Miramax. Unfortunately, after only making a handful of stand-out movies, those big companies started clawing back control and insisted on making final decisions on casting and cutting. The life was quickly sucked out of Alive Films!

As one may expect from the title, Shocker is a livewire of a move and full of energy from the start. It kicks off in familiar teen movie territory. Jonathan (Peter Berg), is a stereotypical college ‘Jock’ on the football team, distracted by his blue-eyed-blonde, all-American girlfriend, Alison (Camille Cooper). There’s snappy dialogue and a bit of good-natured knockabout comedy in the first few minutes, but that serves to make the following scenes even more intense. The tone soon takes on a Nightmare on Elm Street vibe as aspects of reality begin to break up.

As he walks Alison home, Jonathan notices a sinister-looking TV repair van parked outside his house. On hearing screams, he rushes in to witness the brutal murders of his mother, younger brother, and little sister. Then he wakes up from the nightmare, but it turns out to be a premonition. His foster father, Lt. Don Parker (Michael Murphy), is the detective in charge of tracking down a particularly vicious serial killer who specialises in murdering families in their homes. The sadistic madman specifically targeted his family to up the ante in their battle of wits.

Acting on information gleaned from Jonathan’s dreams, the police are able to track down the killer TV repairman: Horace Pinker (Mitch Pileggi). Initially, he escapes via secret passages in his rundown shack but Jonathan now knows that when Pinker kills, he’s able to dream himself into the scene—a plot device similar to the John Carpenter-penned Eyes of Laura Mars (1978). However, Jonathan is at football practice and not asleep, when Pinker targets Alison.

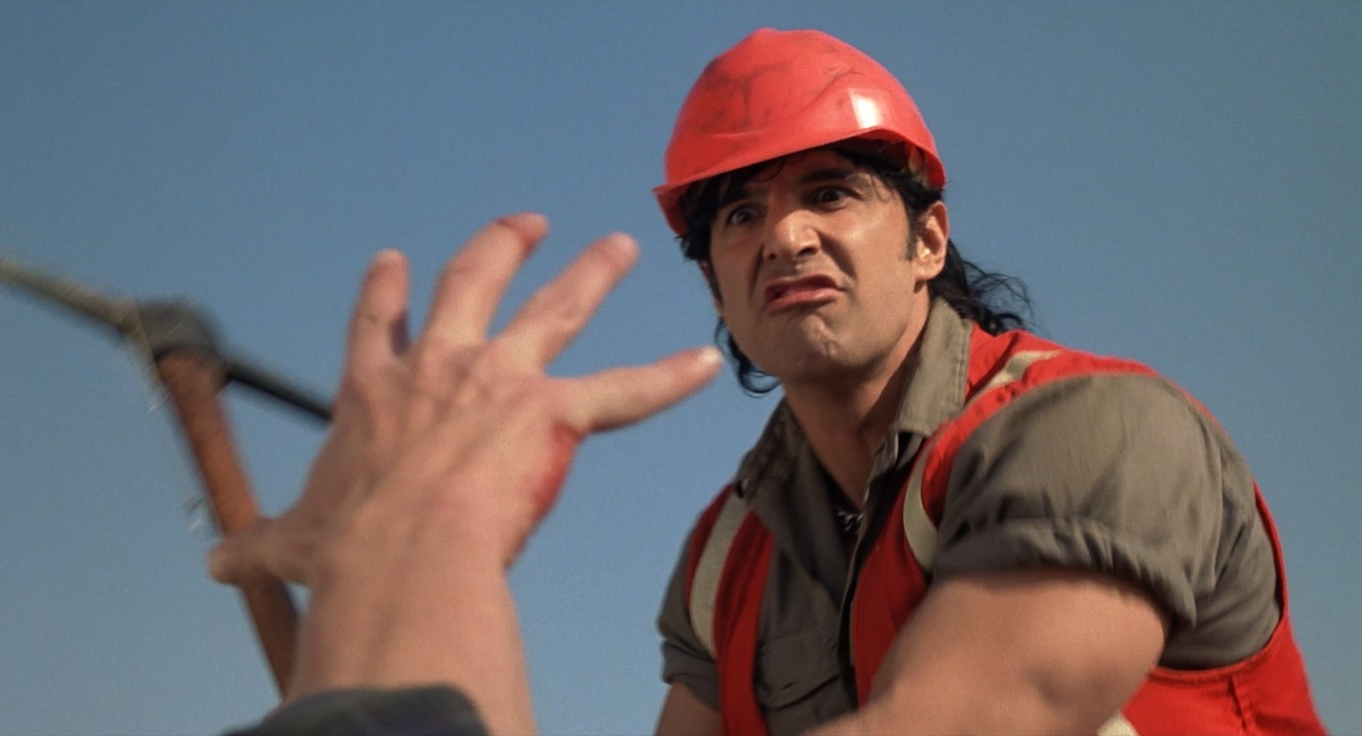

Pinker is eventually tracked down, interrupted mid-crime, and after a chase across the rooftops is finally apprehended. He’s sentenced to death and executed in the electric chair. So far, it’s been a successfully suspenseful slasher movie that expertly executes all the expected clichés. But, we’re only 40-minutes into its 110-minute runtime and, although it may feel like the conclusion to a satisfying thriller, that’s really just the set-up. Things get weirder from hereon in…

Inevitably, Shocker drew comparisons with Craven’s earlier, more successful film, A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), that mapped-out a similar territory of overlapping realities with action taking place on the dream plane. It does have a very similar feel, which is hardly surprising with the same writer-director and with cinematography by Jacques Haitkin again. By the time Craven was making Shocker, the Elm Street franchise had been wrested from his control and already ran to five films, made to an increasingly tired formula.

Shocker can be divided into three distinct segments that could’ve been strung out to make a three-film series. It seems that this time around, Craven created another inventive horror villain but, rather than letting go of Pinker, as he had Freddy, Craven made a film and two sequels in one go and compressed them together, making Shocker a richer and much more satisfying movie.

With Shocker, Craven pushes the dream metaphor further and begins to analyse mass media as if it can be read as the dream of society. Or a nightmare. The obvious subtext, that violent media can desensitise us and normalise abhorrent behaviours, has been criticised by some as being far too blatant. But isn’t that like criticising a story for being too clearly conveyed? Besides, there’s a lot more going on than a simple retread of its central ‘violence-begets-violence’ moral.

The overarching premise evolved from the theories of Marshall McLuhan, which were also the source material for David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983). In the 1960s, McLuhan proposed that the presence and format of media, in itself, could change society. The ways in which media are created, controlled, and distributed can have a far greater effect than the information they contain. He summed that up in his catchphrase, “The Medium is the Message”.

For example, when television caught on, it changed many aspects of society from how people arranged the furniture in their living rooms to how families interacted. It led to the coordinated use of electricity, so people boiling kettles in the advert breaks could drain power and cause outages. It also allowed those who controlled its content to simultaneously beam their mediated versions of a tailored reality directly to a passive audience of millions.

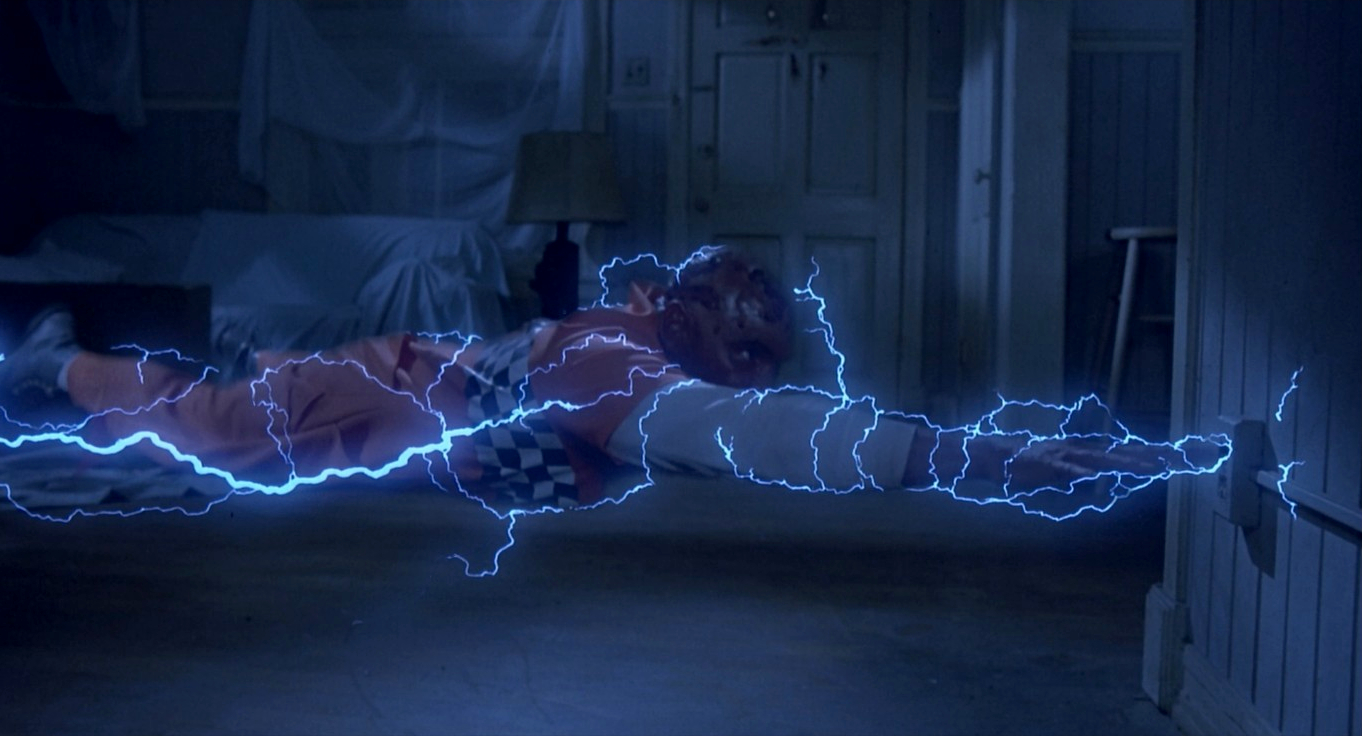

Apparently, as a result of some sort of voodoo ritual, Horace Pinker has been imbued with the power of electricity itself. His final request had been to have a television installed in his Death Row cell and in a striking scene, highly reminiscent of Dr Emilio Lizardo (John Lithgow) feeding on sparking electrodes in The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension (1984), he connects himself to the television’s supply and summons some sort of entity from the airwaves.

From the electric chair, Pinker delivers a tirade at Jonathan, who had requested to witness the execution. He claims to be Jonathan’s real father, explaining that his distinctive leg-dragging limp is a result of being shot in the knee by Jonathan as the toddler tried to stop his father murdering his mother. When the switch is thrown the condemned man somehow survives the volts and then mysteriously burns away to nothing. He has become the medium itself. He’s now able to transfer his energy into another body, taking over the electrical impulses that control our brains and bodies.

Craven admits to being inspired by John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982) and Jack Sholder’s The Hidden (1987), both films that involve an entity being able to jump from one body to another, thus hiding in plain sight. Something that can also be a broad metaphor of how ideology can spread like a virus, radically changing people whilst their outward appearance remains unaltered. He deliberately draws parallels between different networks: the power grid, the interconnectivity of electronic media, and our own neurones.

This also refers back to McLuhan, who stated that all media are the extensions of organic human faculties. The screen, page, and stage are all extensions of sight. Our hearing extends through media as soundtrack, loudspeaker, or headphones. The microphone, telephone, and recordings attenuate our voices. We use touch to interact with keyboard, swipe-screen and other equipment. When driving, our awareness expands to fill the shape of the vehicle. Our thought, however, is mirrored and progressed in microprocessors and interaction with narratives. If the screen is an extension of our visual cortex, then the boundaries become blurred as the nerves within our brains interface with mass media—both complex electromagnetic networks.

Mass communication networks transfer electromagnetic data in a way that echoes the internal electrochemical data that holds our memories and impulses. This feeling of the modern world being interconnected by electricity is counterpointed by the natural world being connected by water. We’re also made mostly of water and thus part of the water cycle—falling as rain, flowing into lakes and into rivers, finally released back into the oceans. It also connects all life on earth and has been used as a metaphor of the subconscious by psychologist C.G Jung.

In the mythology of many ancient cultures, water flowed between the worlds of the living and the dead. Lakes could be gateways to the underworld. So with Shocker, Craven and Haitkin (his cinematographer) use subtle changes in hue to imply a gradual submersion as Jonathan gets closer to connecting with his subconscious.

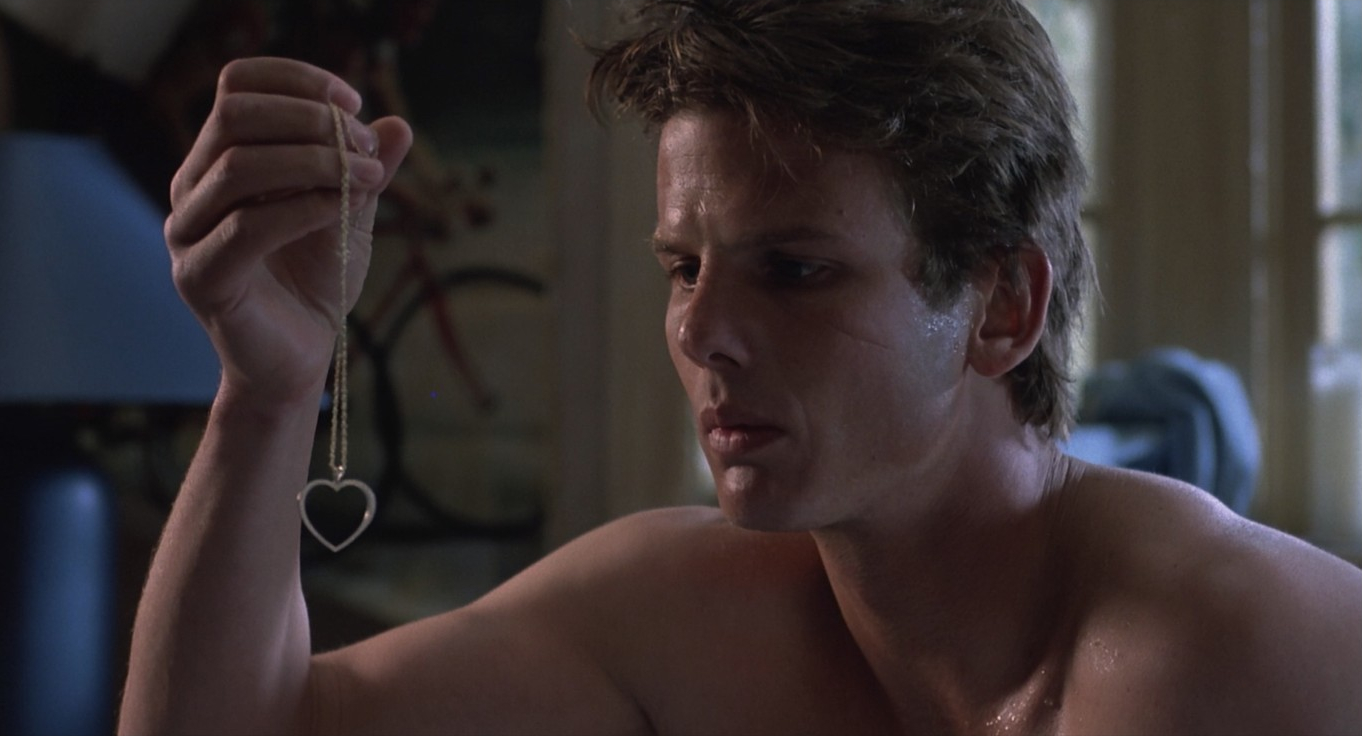

They repeatedly repainted the sets using a progressively subdued colour palette, change the mood and support this subtle narrative thread. Also, it’s no accident that whenever the ghost of Alison appears she’s dripping wet. First with blood, later in a body of water. Jonathan dives into a freezing cold lake to retrieve the necklace that was miraculously brought back from the other side. It is a symbol of their love and becomes an amulet with the power to save him.

If that wasn’t enough subtext to chew on, Craven also continues to examine his fascination with the cycle of violence and the idea of inherited traits: ‘the sins of the father’. He was raised in a strict fundamentalist community that exploited the fear of sin as a method of ‘brainwashing’. Watching films was forbidden. He was told they were sinful. Of course, when he achieved some degree of freedom whilst at college, he sought out this elicit pleasure and sneaked in to watch To Kill A Mockingbird (1962). He fell in love with the medium’s power to persuade and questioned the values of his parents.

Craven highlights this theme by having both his children cameo. His daughter, Jessica, is one of the first characters we see, working in a refreshments kiosk where she comments to Jonathan how appalling the news is and he replies “if you don’t like the news… change the channel.” His son, whose real name is also Jonathan, shows up later as a passer-by in a park who gets taken over by the electric Pinker.

Like many of Craven’s films, Shocker embraces violence and exploits its dramatic potential without glorifying it. Yes, it’s entertaining and even some of the extremely brutal and bloody scenes are lightened with his hallmark dark humour and cheesy asides. After all, it’s a horror film!

Horror films always attempt to fulfil a desire to be shocked and threatened within a context of safety. They’re basically doing what Grimm’s fairy tales do for children. They help build resilience by showing us archetypal representations of evil and all the threats we may come across when we venture out there into the world.

Craven finds it saddening that when we encounter violence in the real world, our response is all too often one of violence. In his first film, the infamous ‘video nasty’ Last House on the Left (1972) he showed how readily average people can rationalise their own violent actions when confronted by the irrational violence of others.

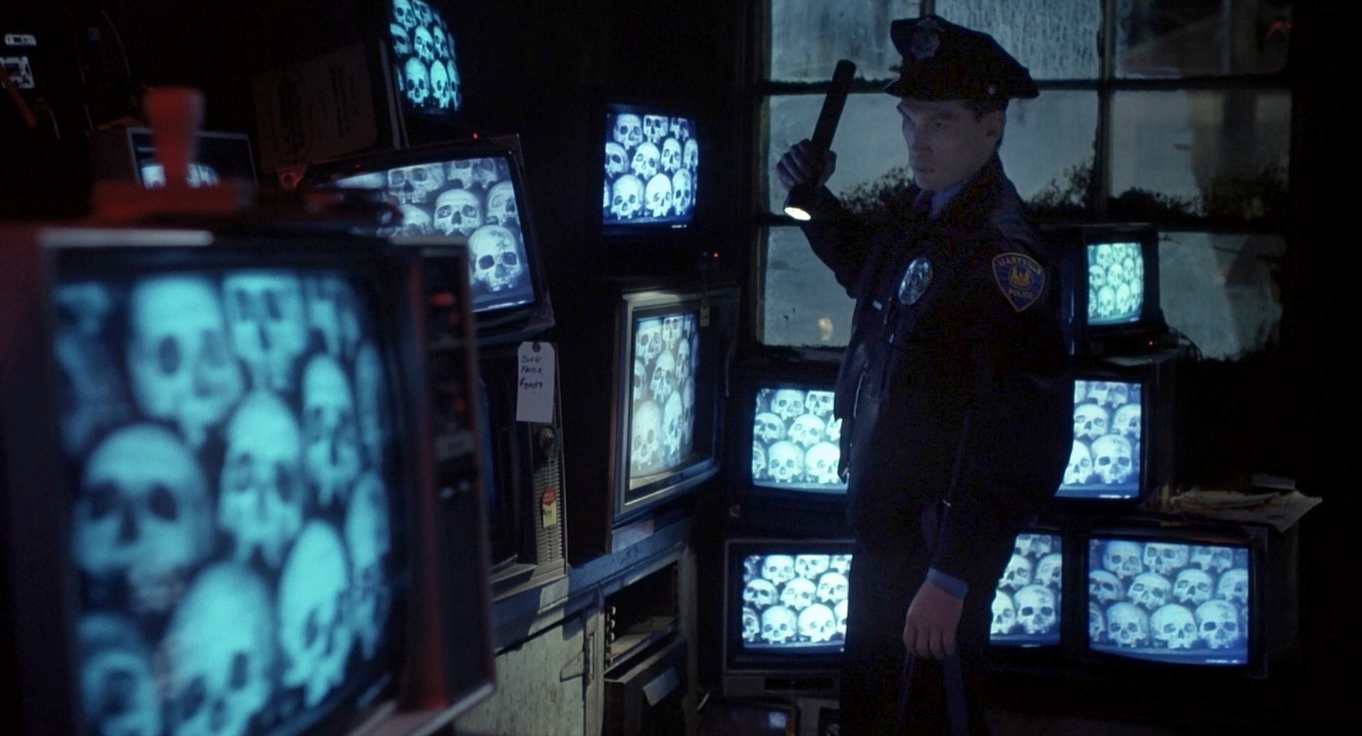

In Shocker, the psychopathic murderer is executed by the state. Again, criminal violence is met by justified violence. The cycle completes. That’s why the televisions appearing throughout Shocker nearly all carry violent imagery, predominantly authentic news footage from war zones. Wars being acts of mass violence perpetrated as an aggressor is met by opposing violence.

There’s also a common theme that runs through this and many of Craven’s films of youth defying and defeating their elders. Breaking a cycle of lies or abuse. Highly relevant these days as we see huge climate demonstrations led by school children and teenagers, bravely speaking truth to power and refusing to accept the heritage of destruction handed to them by their forebears.

But even with these heavy themes in the background, Shocker is great fun! There’s never a dull moment. There’s something innately similar in the structure of humour and horror. Both rely on a benign violation. If we don’t feel challenged, then it’s boring. If we feel too challenged, then it’s offensive. But get the balance right and constructing a scare or a joke is a very similar process. First build expectations, then confound them. The unexpected conclusion causes confusion, and this causes a brief breakdown in rationality, which can lead to either to a laugh or a scream. In this respect, Shocker works as both horror and comedy and certainly confounds our expectations with its crazy third act.

When the electric ‘ghost’ of Pinker discovers he can become electromagnetic energy, he enters the power grid and eventually learns how to broadcast himself like a television signal. Jonathan pursues him into the virtual reality of TV and there’s a great channel hopping chase through news, war footage, chat shows… look out for Timothy Leary (the Harvard Professor, Doctor of Psychology and pioneer of virtual reality) in a rare cameo as a television evangelist!

It’s these dodgy video effects that many have derided. Even Craven admits he wasn’t happy with the result. Apparently, a nameless special effects supervisor couldn’t deliver what he’d promised. Not only that, he lost the negative he was working on.

Craven found himself with about two weeks left of his schedule and with no budget left, having to rethink and totally redesign the SFX for the film. They were rushed through ‘on the cheap’ and I have to say the results are amazing! I’m really glad they’ve been achieved with the optical video-based technology of the time, it makes them all the more convincing. I wouldn’t want them any different. They fit the mood and the medium perfectly, especially when most of its audience were watching on VHS home rentals…

It may have its many detractors but, just like any good cult movie, it’s also left a transmedia legacy among its admirers. Probably its most credible nod comes from comic creator Frank Miller in his first Sin City story “The Hard Goodbye” when Marv’s executed in the electric chair, surviving the first jolt in a sequence that resembles a storyboard for Pinker’s failed execution.

US punk band Blink 182 homaged its wacky finale in their video for their 1999 single “What’s My Age Again”, where the band run naked through various television ads and shows. Later, a core idea and some of its imagery was recycled for J Horror classic Ringu/The Ring (1998)—remember the dripping-wet ghost girl, whose spirit had somehow been encoded into a video signal, climbing out of a television screen to kill?

Another J Horror, Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse (2001), features a computer virus that opens a portal to the realm of the dead and allows vengeful spirits to travel along phone lines and internet connections. They’re able to ‘download’ the life force from their victims or program them via online videos, inspiring them to kill. Just like The Ring, Pulse was remade in the US in 2006 and, fittingly, that was scripted by none other than… Wes Craven.

Perhaps it’s just me, but I find it hard to fault Shocker. It’s exciting, entertaining, well-paced, and completely bonkers. It’s not afraid to be silly. At the same time, it’s intellectually stimulating. Especially if you want to think about it beyond the final credits. It worked for me and left me smiling, which is a lot more than can be said for many other horrors that take themselves way too seriously.

writer & director: Wes Craven.

starring: Michael Murphy, Peter Berg, Cami Cooper & Mitch Pileggi.