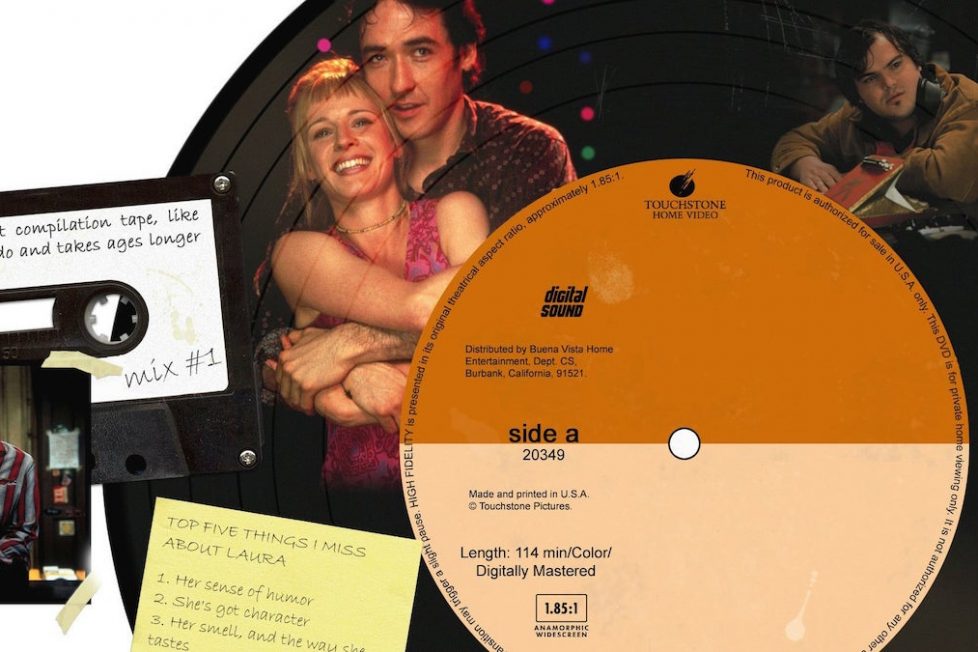

HIGH FIDELITY (2000)

A record store owner and compulsive list maker recounts his top five breakups, including the one in progress.

A record store owner and compulsive list maker recounts his top five breakups, including the one in progress.

“It’s what you like, not what you are like”. This statement might sound like a pithy summary of teenage life but, actually, it’s a quite sad and cutting commentary on adult life. One that fits uncomfortably well. It’s a line that reaches out of a film and slaps you round the face, leaving you with a stinging red mark and the thought “they’re not talking about me, are they?”

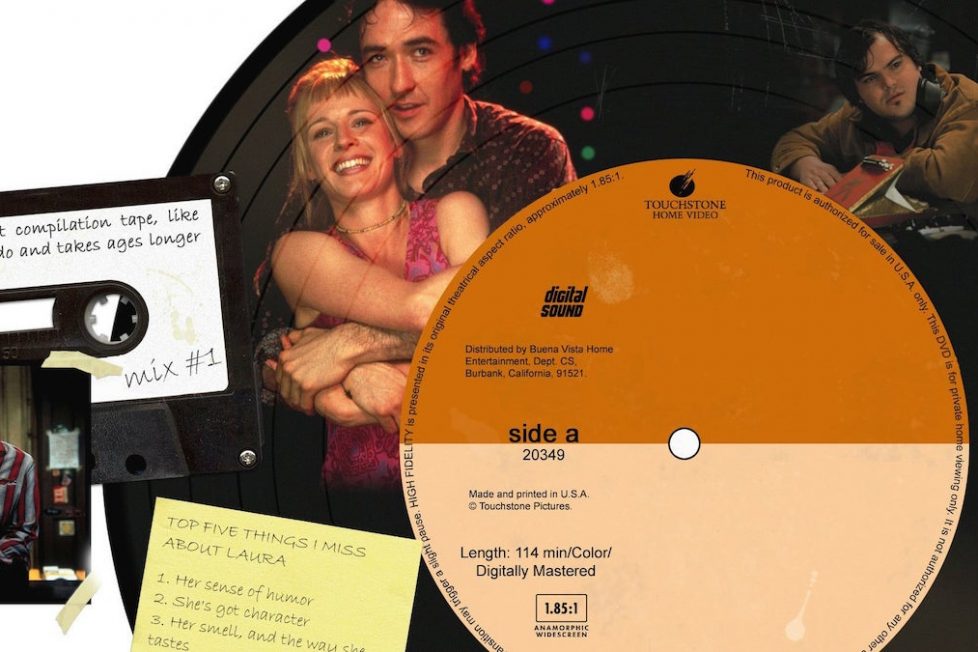

That choice cut of cynical wisdom comes courtesy of Rob Gordon (John Cusack), the surly and affected record store owner and anti-hero of High Fidelity. The film, a pillar of Gen X cinema, charted that generation’s malaise as it moped towards middle-age. Rob’s going through a breakup, but when isn’t he? Through narration and flashbacks, we find Rob in endless states of breakup and pre-breakup, aching in self-pity as he clutches aged vinyl and chain-smokes his nights away.

The romantic episodes of Rob’s past are presented in a list format, which is oddly prescient considering our current listicle-obsessed culture. His ‘Top Five Breakups’ may have sounded absurd 20 years ago, but today it’s a worryingly normal concept. Thank goodness Rob didn’t blog. The story positions us as an invisible audience to his diary. The pain he romanticises isn’t blasted at everyone, just a select unlucky few: us, his colleagues, and most significantly, his ex-girlfriends.

Talking directly to the camera, Rob takes us through years of romantic misadventures, supposedly endeavouring to shatter the mythologising that he’s pumped them up with. His aim is to figure out what makes him such a loser in love. But does he truly want to figure things out, or is coming to a conclusion an accidental byproduct of wallowing in the pain of the past? His quest isn’t a noble one. Rob isn’t setting out to fix himself or to figure out what mistakes he’s making; he’s setting out to poeticise his pain and vilify the women who had the gall to leave him to it. He even dares to take us back to a girlfriend he had at 13 as if schoolyard flirtation is cause for a man in his thirties to mope around his apartment to Bob Dylan breakup songs. You might wish at times that you could break up with him.

It’s a wonder, then, that High Fidelity still thoroughly works. The screenplay, adapted from Nick Hornby’s namesake novel, credited to four different writers (including John Cusack), fizzes with charm and warmth that underlies its sharp insightfulness. It finds its key substance in deconstructing Rob, whilst never losing sight of the fact that its main function is to be an entertaining and funny romantic comedy.

The script’s filled with perfectly-structured exchanges, excellent music cues, and flights of playful whimsy, such as Tim Robbins as a beautifully punchable New Age boyfriend, and Bruce Springsteen appearing to Rob in a vision to offer—what else?—advice on his love life. There has grown a cosiness and familiarity to the movie. Rob’s towers of stacked albums feel homely rather than lonely. And you can easily have a good time playing spot-your-favourite-album, as the artwork to dozens of albums make cameo appearances on Rob’s shelves and in his shop. There is a comfort and recognisability to the art direction that makes it feel lived in, and might make you wonder where you can find a Pavement tour poster. It’s true what they say about the 20-year cycles that trends move in.

But the film has a not-so-secret weapon, and only seconds into its appearance, its scatting, air-guitaring, and strutting – announcing a new comedy superstar: Jack Black. The actor had made minor appearances in several high profile features and had comedy credentials from his part in cult rock-comedy band Tenacious D and an appearance in an iconic Mr Show sketch. This was Black’s first introduction to a mainstream audience, and he rockets out of the gate as if this was the moment he’d been waiting for this his whole life. He’s the explosive arrival that makes an audience sit up and listen. Put another way, if he were a song on an album, he’d track one on Led Zeppelin’s III: Immigrant Song.

Barry and Dick (Todd Lousio), both clerks in Rob’s store, give the film its oddball soul. Barry refuses to sell records he doesn’t rate, while Dick awkwardly converses about Green Day’s influences with an equally-dorky customer. They might be snobs with the social skills of, well, record-store clerks, but in the manner of Clerks (1994) heroes Randall and Dante, we find ourselves wanting to hang out with these guys. We might not want to in real life, but I suppose that’s part of the magic of the movies.

Blessedly, Barry and Dick aren’t relegated to the platitudinous best-pals that exist in romantic-comedies to simply give life advice. In fact, they don’t really care at all about Rob’s love life. Each of the three men is as emotionally inert as the other. That might explain why Rob feels so at home at work, and why his apartment so resembles a record shop with a bed in it. All he does is go back and forth between this work that looks like home and a home that looks like work.

They’re pretty lonely places. The shop rarely pulls in more than a few devoted customers looking for rare Captain Beefheart pressings, while the apartment has even less life than that. We’re Rob’s captive audience. But Cusack’s performance is so boldly unlikable that he’s almost… likeable. By this stage in his career, Cusack had long since aged out of the cutesy teen roles in films like The Sure Thing (1985) and Say Anything (1989). But here, he weaponises that aged-up cuteness. Instead of being charming and youthful, he’s self-assured and emboldened by misplaced confidence. You can see Cusack playing it out when he moodily sips a beer or rolls cigarette smoke out of this mouth as if he were Bernard Black’s American cousin. Rob thinks he’s still pretty cute, but he wouldn’t call it that. He’d call it brooding.

Cusack nails the needy self-interest that defined the decade, when the Gen X’ers decided that, though grunge was dead, there were other ways to mope. Sure, Rob might be young, financially stable, and own his own vinyl store, but, in the grand tradition of stories about comfortable Americans, he wonders: why is it not enough? His problems are at once laughable and relatable, and that’s why the film needed a nuanced and character-oriented director like Stephen Frears. We laugh at Rob, but we also get it. No matter who you are, there are doubtlessly moments of High Fidelity that’ll hit home.

Take, for instance, Rob’s obsession with telling his life through other people’s work. He has Top Five songs for every occasion and mix-tapes filled with tracks that say things that he cannot. What makes the film sharp and perpetually relevant is that this accurately presents what we all do, whether we realise we’re doing it or not. What person with access to the internet, or even a notebook, hasn’t listed their favourite songs, collated their all-time favourite recording artists, or talked about art in terms of star ratings? It’s mechanical but emotional. Rob and his colleagues treat musicians as if they were sports teams with the goal of scoring points. To borrow a metaphor from Moneyball (2011), you can convert something—be it sports, or music—into numbers, and you can analyse those numbers, but you can’t convert the intangible magic that lies between the numbers. Some things are unquantifiable.

High Fidelity is, more or less, about someone learning that lesson. It’s an endlessly satisfying film because it feels earned. Rob’s developments don’t come through deus ex machinas or plot contrivances, they come through conversations. The first of Rob’s conversations with ex-girlfriends are self-serving but, by the end, he’s talking to these women in a way that approaches honesty and self-reckoning. As wonderful as pop-culture can be in life, it can be something that distances us from others too. We might use it to define ourselves, or as a balm for our wounds…. but is that not just filling a gap? By doing this, are we putting off doing the work ourselves? Is music a drug that allows us to wallow? Shouldn’t it be something that puts us in touch with how we feel, rather than making us feel worse?

Rob uses songs like he uses the women in his life—to fix himself, to give credence to his misery, and to define himself vicariously. But High Fidelity isn’t a stuck record and doesn’t end where it begins. In fact, it shakes off that Gen X cynicism enough to suggest we can change the things about us that hurt ourselves and others. Always careful not to stray into Hollywood rom-com territory, the film’s improvements are modest. When Rob proposes to his on-off girlfriend, Laura (Iben Hjejle), it’s not a grand gesture. All eyes remain dry. She laughs at the lack of romanticism in his statement. “I never seem to get tired of you”, he tells her. It’s un-flowery but honest, and mimics a half-romantic, half-defeated line of her’s from earlier in the film: “I’m too tired not to be with you.”

The romantic conclusion is funny, amiable, and tinged with sadness. But then, this isn’t a typical rom-com and its focus was never will-they/won’t-they? High Fidelity is about the relationship we have with ourselves. We’ve all had a conversation with someone who can’t stop talking about their problems with others, almost impressive in their lack of awareness that they’re the common problem. Instead of listening to their stories about people you don’t know, you end up listening to them, and the way they talk, wondering when the other shoe will drop. High Fidelity is that other shoe dropping, a moment of miraculous self-awareness that comes after some tricky and painful reflection.

There’s an Elliott Smith lyric from the song “Colour Bars” that goes:

Everyone wants me to ride into the sun / But I ain’t gonna go down / Laying low again, high on the sound

It’s a beautiful song about expectations and manufactured personalities. It’s not in the film, but it’s probably something Rob would listen to. It explains his mindset quite well but, by the film’s end, the song doesn’t apply so easily. He may not quite ride into the sun, but he’s moving in the right direction.

Music becomes a shared, communal expression rather than an insular and bitter gesture. He’s now making a mixtape for Laura filled with songs that she’ll like. It’s part of growing up; you’re no longer shouting at anyone who’ll listen about what you like, but you’re listening to other people about what they like. The mono recording becomes stereo. As Joni Mitchell might put it, Rob’s looking at love from both sides, now.

Early in the film, Rob deconstructs the art of the pop song, highlighting how depressing many of them are. “Did I listen to pop music because I was miserable? Or was I miserable because I listened to pop music?” he ponders. High Fidelity wonders something similar: “Do we watch romantic comedies because we’re miserable, or are we miserable because we watch romantic comedies?”. Stephen Frears’ film is particularly good because it enjoyably takes aim at romantic comedy characters and makes us wonder why we care about these people in the first place. It asks us if the idealised lives of rom-com characters are really making us feel any better. Are these kinds of films presenting something so unattainable that we’re left jealous and miserable, or worse yet, are they demonstrating just how dissatisfied we’re always bound to be with our lot in life?

But, we don’t have to live our lives through films and songs, or the fantasies they suggest. We can, perhaps, use them as a starting point for our self-discovery, rather than the entire journey itself. Maybe pop culture can be the fuel, rather than the fire. I suppose it’s ironic that a film about not defining yourself through pop-culture has come to mean so much to people. The impulse will always be there to express ourselves through other people’s work, and really, there’s nothing wrong with that in moderation. You don’t have to throw out your record collection or stop loving what you love. You just need to make sure you don’t get stuck between the grooves of an ever-skipping record.

director: Stephen Frears.

writers: D.V DeVincentis, Steve Pink, John Cusack & Scott Rosenberg (based on the novel by Nick Hornby).

starring: John Cusack, Jack Black, Lisa Bonet, Joelle Carter, Joan Cusack, Sara Gilbert, Iben Hjejle, Todd Louiso, Lili Taylor & Natasha Gregson Wagner.