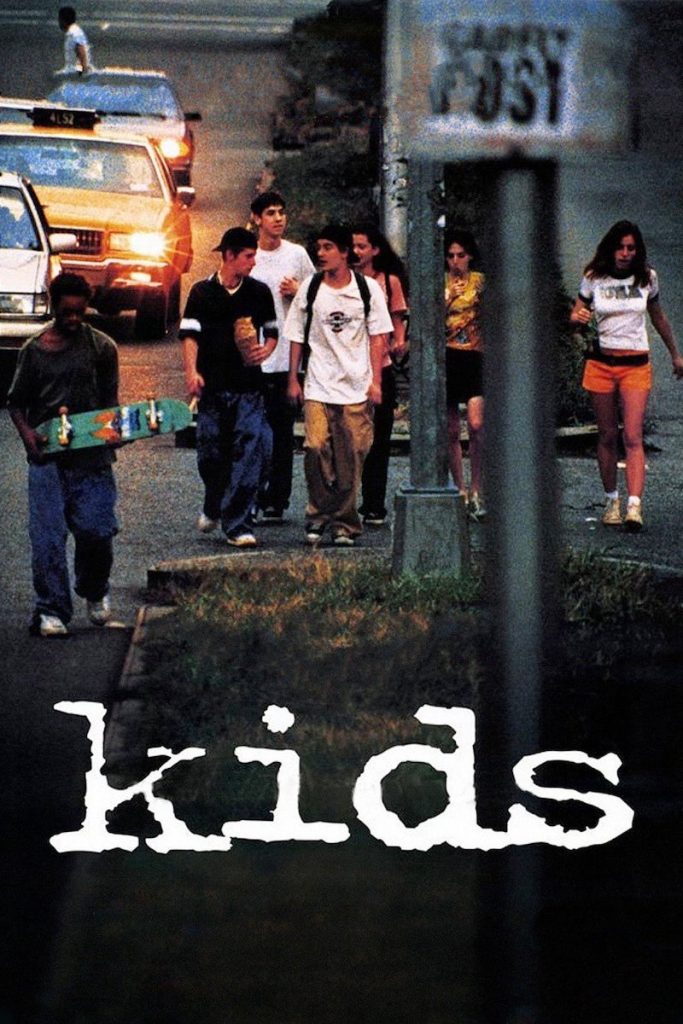

KIDS (1995)

A day in the life of a group of teens as they travel around New York City skating, drinking, smoking and deflowering virgins.

A day in the life of a group of teens as they travel around New York City skating, drinking, smoking and deflowering virgins.

Larry Clark’s Kids isn’t an enjoyable or entertaining film, in the normal sense. Its characters are almost uniformly unattractive; the boys are dedicated to exploiting the girls, and the girls themselves aren’t much better. And they’re sketches rather than full portraits; although they seem very real, we learn little about them.

There isn’t even much of a plot, just two nominal quests for Telly (Leo Fitzpatrick), who longs to seduce two virgins in a single day, and Jennie (Chloë Sevigny), who needs to give Telly bad news. Those provide a basic storytelling structure, but they’re not truly what the film’s about. Kids is mostly impressionistic digressions. Even the dialogue has a thrust and mood that matters more than its words. Yet Kids is, as Rolling Stone put it, “the most notorious teen movie ever made.”

Its notoriety comes from the extreme frankness in how it depicts the New York kids it follows over a single day: young creatures dedicated to sex, drugs, petty crime, and violence. Although Kids isn’t particularly explicit (nude scenes are discreetly shot), one doesn’t imagine first-time director Clark is being reticent. We see everything these teens do; a lot of it pointless, some of it appalling, little of it innocent. Most events are based on actual incidents, Clark’s since claimed.

The film is almost entirely presented in a quasi-documentary tone with constant camera movement, lots of medium close-up from cinematographer Eric Edwards (a Gus van Sant regular), and naturalistic overlapping dialogue that feels improvised even though hardly any of it was. Indeed, so many people thought the movie was a documentary that Fitzpatrick left the US after Kids was released, to avoid the opprobrium of viewers outraged at the character Telly’s amorality.

It is, then, both the often grim subject matter and the apparently casual realism which give Kids its impact.

I say “apparently” because on closer inspection it’s a precisely constructed film, with two narrative threads progressively twisted together, and not just a passive recording of events. For example, the vicious sequence where a gang of boys beats a man to unconsciousness, spitting on him as he lies bloodied on the ground, is followed by a cut to a nicely-lit, impeccably turned-out Sevigny in a cab whose driver (Joseph Knopfelmacher) will shortly offer some positive philosophising.

This isn’t an accident. Sevigny is the movie’s personification of what could have been good in these kids’ lives but won’t be, and the way she gets steadily more wasted as the story progresses is an allusion both to their self-destructive behaviour and to AIDS, which is rarely mentioned but always looming in the background of Kids.

Then there are the tiny details Clark and Korine work in; throwaways that lend some humour to the generally depressing tawdriness of Kids. Telly and Casper (Justin Pierce) steal fruit from a street vendor and the camera lingers briefly to watch him rearrange his stall. The boys give the fruit to a cheeky neighbourhood child and she throws it away. The film’s whole ambience of aimlessness encapsulated in a quick vignette, perhaps, but amusingly so.

And then there are the bizarre buskers, the legless black panhandler with the ‘KISS ME I’M POLISH’ T-Shirt, the posters for bands like From Good Homes and Violent Femmes that have to be there as commentary. Perhaps even the fact that Telly and Casper travel on the same subway featured in The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974) is a hidden nod to a more romantic imagining of New York gritty realism?

It is, then, a deceptively careful film. But what’s harder to be sure about is whether Kids is taking a moral stance. It’s certainly possible to interpret it as advocating safe sex and “just saying no”, and the final scene is desperately sad—when Casper asks “Jesus Christ, what happened?” he may superficially be talking about the post-party wreckage of his friend’s apartment, but it’s clear that his words have wider import.

It might be dangerous, though, to leap to the conclusion that Kids itself shares his shock. Everything in the movie has been presented flatly, dispassionately, without comment. Here at the conclusion, it’s surely only Casper (who seemed to have more self-awareness than some of the other kids), who is disturbed. Clark is merely his chronicler.

Whether it’s a cautionary tale or a slice of life, however, there remains another issue with Kids that has contributed heavily to its notoriety and may seem even larger to us today, in an era so aware of paedophilia.

The film is the work of a director in his fifties (although Korine, the writer, was only 22 when it came out) that covers teenage sexuality extensively and unflinchingly. The first scene, indeed, depicts Telly (who’s about 16, although it’s never stated) with an even younger girl, both of them nearly naked on her bed, teddy bears in the background. Some explicitness was cut from this following the preview at the Sundance Film Festival, but even so, merely showing such a thing at such length was taboo-breaking.

Undeniably, too, the camera throughout Kids takes a great interest in adolescent bodies, especially (though not exclusively) the male ones, even when they’re not germane to the narrative—such as it is.

This is inescapably troubling. Yet it’s difficult to imagine how a film that sets out to be honest about the lives of hedonistic teens could do anything other than show the almost unshowable. And Clark’s background as a photographer is evident. His acclaimed 1971 collection Tulsa has many similar images, and there are times when he’s clearly using bodies in Kids for purely photographic effect. The row of shirtless youngsters crammed together on a sofa, for example, or the almost sculptural sleeping figures strewn around the apartment at the end.

In any case, while there were the inevitable accusations of pornography, the sex and the nudity (which is actually modest, but there’s so much) were important factors in Kids achieving such infamy in 1995, and for a low-budget indie it was a big hit. Reviewers were often unsure what to make of it, but many offered applause. Variety called it “disturbing precisely because it is so believable”, while The New York Times observed that “its semblance of realism immediately raises questions… is this a lurid and cynical exaggeration?” before concluding that “its extremism is both artful and devastatingly effective”.

It’s not just Clark and Korine who deserve praise for this, however. While their direction and script operate ceaselessly in the background to ensure that the seemingly unforced, spontaneous Kids nevertheless hits the right beats at the right points, it’s the cadre of inexperienced actors who carry it from moment to moment. We may not like these kids, but they’re so persuasively real there are times when we can’t help caring about them.

Foremost is gangly Fitzpatrick, a brilliantly non-obvious choice for a teenage Lothario. He has character and presence and you never doubt his lines and actions are things this kid would say and do. Pierce is his perfect foil, more obviously cool, but perhaps more insecure too. Sevigny, one of two who became a big name alongside Rosario Dawson, is slightly more actorly than them, but just as credible.

Among the host of lesser teens, Harold Hunter stands out, but the few adults that appear are peripheral. Which is as it should be, because in large part the point of Kids is that it doesn’t filter young people through adult perceptions or a grown-up plot. We get them on their own terms, and if those terms aren’t always nice ones, we have no choice but to accept them. This is what (some) teenagers are like, Kids seems to be saying. You’re welcome to object, but even if you turn away, it’s still a reality with its own kind of terrible beauty.

USA | 1995 | 91 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Larry Clark.

writer: Harmony Korine.

starring: Leo Fitzpatrick, Justin Pierce, Chloë Sevigny, Rosario Dawson, Yakira Peguero, Atabey Rodriguez, Jon Abrahams, Harold Hunter & Sajan Bhagat.