THE NIGHT OF THE GENERALS (1967)

In 1942, a Polish prostitute and German agent are murdered in Warsaw. Suspicion falls on three generals, and Major Grau of German Intelligence seeks justice which ends up taking decades.

In 1942, a Polish prostitute and German agent are murdered in Warsaw. Suspicion falls on three generals, and Major Grau of German Intelligence seeks justice which ends up taking decades.

As a World War II story, Night of the Generals isn’t only unusual in being told from a perspective entirely within the Nazi ranks, but its main plot strand is a classic whodunit murder-mystery. There are also noir undertones and a few key elements that prefigure many pulp euro-thrillers of the 1970s. It’s a neglected classic and oft-overlooked for a movie I believe has been a huge cultural influence, and high time it was reappraised. So, I am very pleased that Eureka Entertainment has given it the Blu-ray treatment and presented us with a lovely restored edition.

Although I’m not an avid fan of historical war films, I have a handful of favourite: James Clavell’s The Last Valley (1971), Lewis Milestone’s All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), Andrei Tarkovsky’s Ivan’s Childhood (1962), Sam Peckinpah’s Cross of Iron (1977), Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979), and, most recently, The Book Thief (2013). All unusual examples that use the milieu as a stage for another story they need to tell.

I would certainly rank Anatole Litvak’s Night of the Generals up there with those. I note one factor these films share is that all, bar one, aren’t told from the more popular perspective of the British-American Allies. In other words, not focussing on characters that our histories tell us are the ‘good guys’. This makes things less ‘clear-cut’ and forces the writers to more carefully consider and justify their content.

I could write a monograph on the title sequence alone, which was designed by Robert Brownjohn and shot as a separate entity, which seemed to be a trend in those days for quality movies. Brownjohn is best-known for designing the iconic titles for the second Bond film, From Russia with Love (1963), in which he built on the silhouette motif introduced by Maurice Binder with Dr No (1962). Both were graphic designers who were coming out of the swinging jazz and pop art scene of the late 1950s. Brownjohn’s innovation of projecting and re-filming, famously onto the scantily clad bodies of sexy ladies, was one he learned from studying under an ex-Bauhaus teacher, László Moholy-Nagy, at the Chicago Institute of Design. Moholy-Nagy, a filmmaker and graphic designer himself, was a refugee from Nazi Germany after the German government under Adolf Hitler shut down the Bauhaus Design School there. The displacement of Bauhaus teachers and their students, mainly to Switzerland, Britain and the USA is probably the single most important event that influenced most aspects of post-war design.

For his title sequence here, Brownjohn deconstructs the iconography of a Nazi general’s uniform. He lingers fetishistically on the insignia, the medals, the textures of the grey fabric and the predominance of black leather. The gloves—yes, here we have an early example of ‘the black-gloved killer’ trope. The scabbard and the long knife that slides from it. Finally, the gleam of jackboots in the dark. He uses very little colour except for bold red—a visual cue picked-up throughout the rest of the film and later by many a giallo director to foreshadow bloody murder.

His use of a red light bulb swinging on its cord until it pops, symbolising a building bloodlust until it can no longer be restrained by sanity and gives in to the consuming darkness, is also visually quoted in subsequent thrillers. The sequence is very reminiscent of Dziga Vertov’s use of montage in Man With a Movie Camera (1929), in which the Ukrainian filmmaker, a contemporary of Moholy-Nagy, pioneered the language of cinematic editing to construct a sequence where a woman dresses and prepares for the day.

Apart from the slick quality of the titles, the other thing to grab the attention is the stellar cast that reads like a catalogue of the era’s top talent. At the time, much was made of the film being produced by Sam Spiegel, who’d enjoyed a string of box-office successes since The African Queen (1951) that included On the Waterfront (1954) and The Bridge Over the River Kwai (1957). Spiegel himself had started out making films in Germany during the early 1930s until forced to flee by the Nazi regime.

After his experience as a producer of Lawrence of Arabia (1962), which turned Peter O’Toole and Omar Sharif into international sensations, he wanted them both to star in Night of the Generals and, because they were still under their original studio contracts, both agreed to fees much lower than they were getting used to. It was Donald Pleasence who commanded the highest fee among the cast, some say it was twice the combined fees of O’Toole and Sharif.

The story begins in Warsaw, 1942, but will take us to the open city of Paris in 1944 and ends up spanning a 23-year period with a sometimes-disconcerting narrative structure of flashbacks and flashforwards. The start of the film proper, though successfully suspenseful, perhaps seems a little clichéd today. I think that’s because, although employing conventions already tried-and-tested by Alfred Hitchcock, it was to inform many similar sequences since.

We hear, rather than see, the murder and the only witness to the killer leaving the scene watches through a crack in a door. Although he has seen important details, he didn’t see enough to identify the individual. The extreme close-up of the eye framed by splintering wood, the glimpse of the killer from its point of view are shots familiar to any aficionado of the giallo and the rather contrived technique of tantalising us with one piece of evidence, but concealing identity is now a well-used plot device.

It transpires that the victim, who had been stabbed at least 100 times by a maniac, was a prostitute. So, it’s rather surprising when Major Grau (Omar Sharif) of the military police turns up to investigate but it seems that she had been an informer for German intelligence. It’s then suggested that she might have been killed by a Polish patriot who found this out, because “patriotism has been known to have its vicious side,” to which Grau replies “a hundred knife wounds goes beyond normal patriotic zeal!” A thinly-veiled metaphor for the many atrocities of war that go beyond what is ‘necessary’ into the realms of the cruel and criminal.

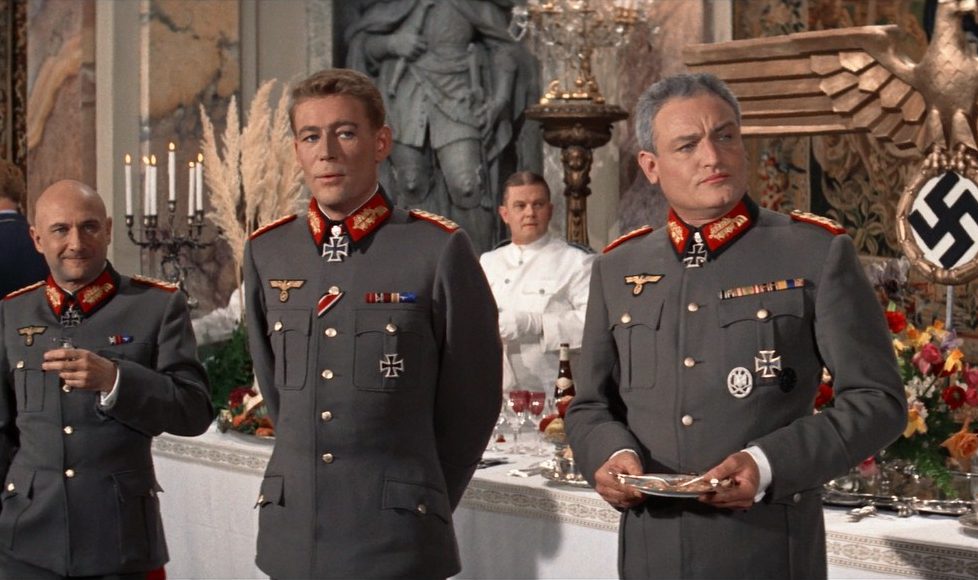

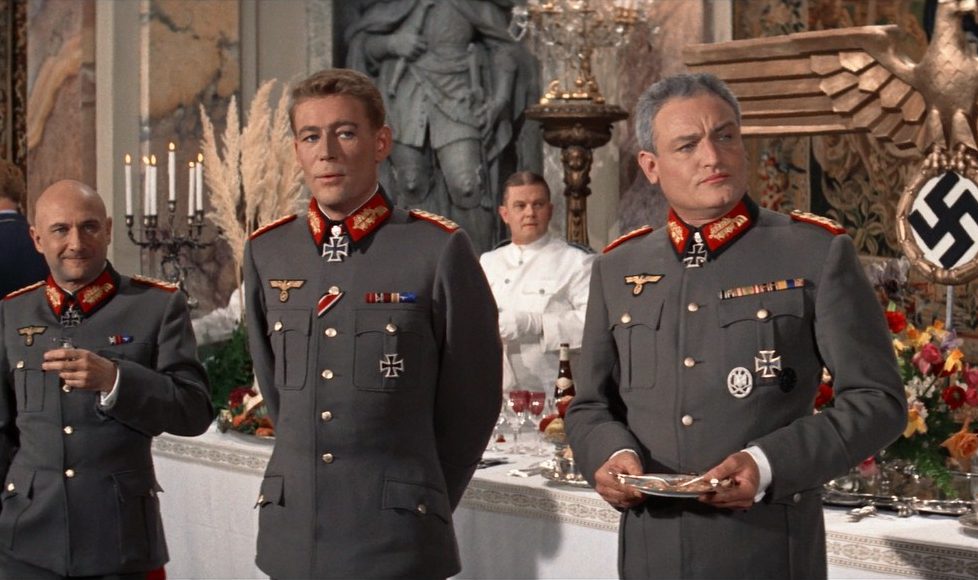

The plot swiftly thickens when the eyewitness, clearly scared witless, describes the pertinent detail he’d seen through the crack. The killer was in uniform, what’s more, the uniform was that of a German General. The look of glee in Grau’s eyes is an essential detail. Sharif was famous for having a twinkle in his eyes, but here he seems overjoyed with the potential of bringing an officer of superior rank to justice. Or is he simply exhilarated by the dangerous challenge, in classic Sherlock Holmes fashion? He then learns that on the night of the murder, there were just three German Generals in town without verifiable alibis. The three titular Generals are played by Donald Pleasence, Charles Gray and Peter O’Toole, and they’re all perfect for the parts.

Despite the passing resemblance to Heinrich Himmler that landed him the role of General Kahlenberge, Pleasence was a respected British actor. He had served in the RAF and was captured in 1944 after the Germans shot down the Lancaster Bomber he was aboard. On his release, at the end of the war, he picked up his acting career. He appeared in British teleplays and was a regular for both the BBC’s Sunday-Night Theatre (1952-59) and ITV Television’s Playhouse (1956-59). In the 1960s he transitioned to the big screen, one of his early roles opposite Peter Cushing in The Flesh and the Fiends (1960) as Hare, of the infamous ‘body snatchers’ Burke and Hare. Among some 15 other appearances that same year, he starred with Stanley Baker in Val Guest’s superb Brit-noir thriller Hell is a City (1960) and Circus of Horrors (1960) for Anglo-Amalgamated Productions.

He quickly established himself as a well-loved character actor who, for a while, was almost ubiquitous in British film and TV, with a reputation for playing oddball villains, as well as proving himself in comedy, cult horror, and adverts to sell “the odd lager” Holsten Pills. Genre fans, of course, know him best for Fantastic Voyage (1966), as Loomis in John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978), Professor McGregor in Dario Argento’s Phenomena (1985), and Father Loomis in John Carpenter’s Prince of Darkness (1987), among many others…

One of his best-known roles was Bond uber-villain Blofeld in You Only Live Twice (1967), in which his Night of the Generals co-star, Charles Gray, also appeared as Dikko Henderson. Just to confuse matters, Gray then went on to play Blofeld in Diamonds are Forever (1971). Coincidentally, one of Gray’s first screen appearances was as Sir Blaise in the TV series The Adventures of Robin Hood (1957), which also starred Donald Pleasence as Prince John!

I remember Gray as Mocata in the classic Hammer version of The Devil Rides Out (1968) but will always associate him with Sherlock Holmes since he first played Mycroft in The Seven-Per-Cent Solution (1976) opposite Nicole Williamson’s Sherlock, and then reprised the role opposite Jeremy Brett several times for the ITV adaptations from 1985 until 1994. He too had a long career as a fine British character-actor whose rather Germanic looks are perfectly suited to his role as General von Seidlitz-Gabler in Night of the Generals, which is considered his ‘breakthrough’ role and, just like Pleasence, was prolific over the following decade in a wide variety of roles.

Which brings us to our third general of the night, played by Peter O’Toole, who after plenty of bit-parts and supporting roles, had rocketed to international stardom in the title role of Lawrence of Arabia, for which he received the first Academy Award nomination of his career. He would go on to be nominated for eight Oscars but won none of them. In 2002 he grudgingly accepted an Honorary Award in recognition of such a long and consistently high calibre career.

Just like Pleasence and Gray, he had paid his dues on the British stage before appearing in teleplays for Armchair Theatre (1957), Sunday-Night Theatre, and Theatre Night (1959). For me, his stand-out film roles include Goodbye Mr Chips (1969), My Favorite Year (1982), and the stage and television play Jeffrey Bernard Is Unwell (1999). He voiced Sherlock Holmes in a series of animated films and played Conan Doyle, the iconic character’s creator, in FairyTale: A True Story (1997). Late in his career, he raised his television profile again as Pope Paul III in The Tudors (2008).

O’Toole plays General Tanz as the epitome of the Arian superman, the archetype that Carl Jung referred to as “the Blond Beast”. He’s tall and fair, with cool blue eyes, portrayed almost like a rock-star, a showman—always giving a tightly controlled performance that belies the real man beneath. The character part-inspired David Bowie’s ‘Thin White Duke’ persona and his dalliance with Nazi imagery. The scene where Tanz supervises the flamethrower troops attacking a resistance stronghold whilst standing proud in his open-topped limo, not flinching in the slightest as a soldier beside him is shot dead, reverberates through Lieutenant Colonel Kilgore in Apocalypse Now, a decade later.

Tanz is admired and feared by those around him, a decorated war hero sent to Warsaw, by Hitler himself, to rout-out Polish freedom-fighters and end their resistance. O’Toole provides all the most memorable moments, the strongest being a scene he plays without dialogue: he asks to see the Entarte Kunst or ‘decadent art’ being stored behind locked doors at the Jeu de Paume gallery in Paris. The stash contained many masterpieces of Impressionism and early modern art after it had been looted from French dealers and Jewish family collections. He’s arrested by the piercing stare of a Vincent Van Gogh self-portrait which seems to trigger something deep within his psyche.

It’s an astonishing performance and one of the greatest character studies in cinema. I’d put alongside Robert De Niro’s Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver (1976), or if we want to stay with the Nazi theme, Maximilian Schell’s phenomenal performance in The Man in the Glass Booth (1975). Actually, that’s one thing I can think of that could’ve improved Night of the Generals—if Max Schell had been in it too!

To begin with, all three Generals are suspicious enough. They’re evasive and cannot provide convincing alibis. Plus they’re all Nazis, which kinda makes them look shifty! Their attitudes are in turn, dubious, nervous, and arrogant.

The first half of the film is a kind of whodunit as we work out why they behave as they do. Then, really through a process of elimination, we learn who the culprit is. There is no shocking reveal or Agatha Christie-style accusation, it all just falls into place, piece by piece, until it’s clear who the murderer is. Thing is, those around him don’t know what we know. So, the viewer’s knowledge is cleverly exploited to create slow suspense and a building sense of unease. The characters we are rooting for are now in mortal danger, and not just from the threats that war offers. What complicates things further is some of those behaving in a guilty manner do have something to hide. They are indeed conspiring to commit a crime—but one we may well support: the historic plot to assassinate Hitler.

A fourth General, Rommel (Christopher Plummer), is presented as the figurehead of the conspiracy. The title takes on a dual meaning as this thread develops. The small-scale night of the generals, when three of them were in Warsaw without alibis on the night a prostitute was killed, Ripper-style. Also, the larger scale plot involving numerous generals to eliminate their Fuhrer, whom they had followed faithfully but now believe to be insane. This artificial divide between the personal and political is the major device holding the story together and filling-in the deeper, philosophical subtext that runs throughout the film.

What happens when a stratum of society is either demonised or deified? When the concept of superiors and inferiors becomes institutionalised and some people are deemed to have more value than others depending on some arbitrary factor such as race, class, income, origin, location, type of intelligence, gender, rank, privilege, and so on…

One of the oldest political tricks in the book is singling out a minority element and blaming those for the ills of a society, which then implies that dealing with them will cure a sick culture. The beginnings of that argument can seem rational on the surface—remember that between the wars, the National Socialist Party was democratically elected in Germany. We know them better as the Nazis, and some of their policies initially sounded attractive.

Of course, we now know that those ideas veiled an insidious ideology and were a set of lies designed to manipulate the masses to a point at which they gave up all their democratic power. They had been duped into believing they were superior to others and so became a slave nation to the elite they accepted as superior. Sadly, the lesson seems to need repeating every generation or so, as people forget what happened in the not-so-distant past.

In Night of the Generals, we see the results of this ideology, but we also see a vignette of the same evil in a condensed version. The most detestable, yet sickly seductive villainy on both the political and personal level. The military elite can’t really understand why a detective would be putting effort into finding a prostitute’s killer when all around civilians are being burned out of their abodes, shot in the streets, and carted off to ghettos.

The Warsaw ghettos were little more than waiting areas for concentration camps that were already full to overflowing by this time. So, the ghettos were cordoned off and supplies were severely restricted. The German army in Poland was having enough trouble feeding their own ranks and if the Poles starved, then there would be fewer to transport to the camps. So it’s significant (some might say sadly ironic) when Tanz commands his orderly to give his own lunch to a group of starving street kids and dictates that all guards should carry food for the ghetto children.

Here lies one of the film’s touches of genius: the characters, even those who’re clearly tainted with evil, are still played as human beings. They’re not off-the-shelf, easily dismissed, monsters. It’s even hinted at that the maniac-murderer, once revealed, is a product of the horrors he’s been forced to endure in war. If his psychopathy was not directly caused by the war, the environment created by war and the ideology espoused by Nazis gave him license to give in to it.

If you are told that others are sub-human and you are super-human, then the shadow self begins to justify even those darkest of desires—they can be unleashed on those who are thought to be comparatively worthless. This is a philosophical debate that General Tanz has with his driver, Corporal Hartmann (Tom Courtenay): as two men sitting together having coffee, what difference is there? Yet in rank, one is of more value than the other. If called upon, the subordinate would be expected to sacrifice himself to save his superior…

Tom Courtenay is yet another fine British character-actor. He’d just worked with Omar Sharif in Doctor Zhivago (1965) and was no stranger to playing slightly atypical soldiers after a string of roles in war films such as Private Potter (1962), King & Country (1964), Operation Crossbow (1965) and James Clavell’s King Rat (1965). Hartmann is the character that ties together the narrative strands in Night of the Generals that would otherwise tend to unravel.

At different points in the film, he finds himself under the command of each of the three suspected generals and is a kind of ‘everyman’ antithesis to Tanz. He also provides the love interest as he embarks on an illicit romance with Ulrike (Joanna Pettet), the daughter of General von Seidlitz-Gabler and Eleanore von Seidlitz-Gabler (Coral Browne). One potential criticism that leaps out is that Pettet and Browne are the only two strong female characters in a very manly cast—but then, certainly in the Nazi ranks, wartime was the province of men. They’re both up to the job and stand their ground admirably opposite the male leads.

The film was made on a respectable budget of $5.2M but struggled to claw back just over half that over the next five years. Perhaps audiences expected more action-driven battle scenes, rather than a somewhat cerebral, character-driven narrative. With a run-time of 145-minutes, Night of the Generals has been criticised for being too long. I would disagree as I found it completely absorbing and never felt it drag. I concede that the abrupt jumping back and forth in time did break that spell, but only now and then. The well-structured plot and all-around compelling performances immediately sucked me back in. If anything, I would suggest it could have worked even better as a mini-series. I would have appreciated more time to see the characters develop and change over the years.

There are backstories that remain merely implied, leaving it up to the audience to fill in many gaps in the interim between 1944 and ‘the present’, which is 1965 in the film. And one other thing niggles me: the modus operandi of the psycho-killer. With the kind of frenzied murder described, how did he avoid getting blood all over his general’s uniform? With some imagination, you can figure out how it could be done, but not given the timeframe between the killings and the culprit leaving the scenes, which starts to hint at something supernatural. Hmm, now that would have been a very different story! The real reason for the lack of an explicit explanation probably lies in the sexual nature of the motive and the tight censorship of the time. The film would have run into problems with the Production Code Administration. Established in the 1930s, it was on its ‘last-legs’ by then and was abolished soon after production to be replaced with the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) rating system was introduced in 1968.

For me, it works best as a suspense thriller but it’s a good war film that rings true and sits well against its historical backdrop. That’s probably because the war was in the living memory of a good proportion of the cast and crew and the original novel was penned by a German veteran. Hans Hellmut Kirst was a member of the Nazi Party and joined the German army at the age of 19, later admitting to being convinced by the propaganda of the time that he was being a patriot. He rose through the ranks to become a first lieutenant during WWII but was a career soldier who found himself increasingly at odds with the ideologies of his superiors.

After the war, he became a successful author of more than 60 novels, most of them set among the Nazi ranks, and highly critical of them. Apart from Night of the Generals, he’s best known for the popular five-book series Null-Acht, Fünfzehn/Zero-Eight, Fifteen, featuring Gunner Asch, a young rogue who continually antagonises the military system, yet survives in the army over a story arc that begins with the rise of the Nazi Party and concludes in post-war Germany—it’s thought to be partly autobiographical.

He’s considered to be one of the best popular chroniclers of the rise and fall of the Third Reich, his works containing historical fact, lively characters, and laced with satire. Recurring themes are the disillusioned youth manipulated by amoral superiors, the willingness of those superiors to play along with Nazi ideology while it suits them and to flip to anti-Nazi as their fortunes changed. Many of his books also featured civil crimes being perpetrated under the cover of conflict. He was awarded an ‘Edgar’ by the Mystery Writers of America for Night of the Generals, and this encouraged him to write more detective fiction during his later career.

The novel did fall foul of some controversy over plagiarism of The Wary Transgressor, a 1952 novel by hard-boiled crime writer James Hadley Chase. Apart from the general in Chase’s book was in the US Army, an entire sequence in Night of the Generals is a carbon copy of a chapter from Chase’s book and key plot features such as art treasures, murdered prostitutes, and an innocent man being framed to take the fall for a psychopathic general, were lifted ‘wholesale’. That’s why there’s a writing credit for Chase in the titles: “from the novel by Hans Hellmut Kirst based on an incident written by James Hadley Chase”. The screenplay was adapted by Joseph Kessel, whose 1928 novel, Belle de Jour, was also being adapted in 1967 into a film by Luis Buñuel. Helping with the script was Paul Dehn who had co-scripted Goldfinger (1964) and would also write all four Planet of the Apes sequels (1970-74).

If Hirst was uniquely well-qualified to have written the story, then Anatole Litvak’s experiences meant he was equally entitled to direct it. He became a serial refugee, first fleeing his homeland of Russia, for political reasons, to Berlin where he transitioned from theatre to film. In France, he had his first big break in cinema as an assistant director on Abel Gance’s epic biopic Napoleon (1927) famous for an extravagant run-time of 4-6 hours, depending on which version you see.

As the Nazi’s rose to power in Germany, Litvak settled in France, where he made several films including Flight into Darkness (1935), which incidentally, he adapted from a novel by Joseph Kessel. He then worked with Kessel again on his big international breakthrough picture, Mayerling (1936), about the tragic deaths of Austria’s Crown Prince Rudolf and Baroness Mary Vetsera. The film received critical acclaim and is now cited as a template for the historical romance and credited with developing a style of cinematography that relied on a lot of camera motion, quoted as a major influence on the work of Max Ophüls, who later made Le Plaisir (1952) showcasing this style.

The success of Mayerling brought offers from Hollywood and British Studios, just in time for Litvak to get out of Europe as the war loomed. Notably, he made Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939) starring Edward G. Robinson, which was deemed so accurate that it was banned in Germany, Italy, Spain, as well as some neutral countries including Switzerland and Ireland. He joined the US Army and was assigned to the film corps where he worked with Frank Capra (It’s a Wonderful Life) on a series of training films and documentaries.

After the war, he had his first big hit with the noir thriller Sorry, Wrong Number (1948) starring Barbara Stanwyck and Burt Lancaster. The same year, he received his first Oscar nomination as ‘Best Director’ for The Snake Pit (1948), starring Olivia de Havilland. His second nomination was for the acclaimed war film Decision Before Dawn (1951). He directed more than 40 films during his 40-year career. His breakthrough movie, Mayerling, was remade twice; once by Litvak himself for a TV producer’s Showcase Special starring Audrey Hepburn, in 1957, and again with Terrance Young directing Catherine Deneuve, James Mason, and Ava Gardner in 1968. This version starred Omar Sharif, the year following his lead in Night of the Generals.

The fact that so many of those involved in making Night of the Generals, from the writers, through cast and crew to the producer and director all had first-hand experience of the topics they were dealing with gives the film an extra dimension of authenticity. Pleasence’s experience as a prisoner of war gave him insight into the German military that enabled him to imbue his nervy, alcoholic General with believable humanity. Sam Spiegel was a displaced Jew with roots in Poland giving him a personal investment in the story. Litvak had seen the rise of the Nazis and then fought against them in the US army. Kirst had been a Nazi and fought in the German army, later rescinding that insidious ideology and becoming eloquently critical of it and the military he had been part of.

Few productions dealing with the war could bring so many disparate views and pertinent personal experiences together and due to the intervening years, it is unlikely to ever be possible again. Night of the Generals is an intelligent and unusually sensitive film about war and murder that is very much of its time, whilst contemplating what had happened in another time… and it’s a pretty good thriller.

director: Anatole Litvak.

writers: Joseph Kessel & Paul Dehn (based on the novel by Hans Hellmut Kirst and an incident written by James Hadley Chase).

starring: Peter O’Toole, Omar Sharif, Tom Courtenay, Donald Pleasence, Joanna Pettet & Philippe Noiret.