THE COMMUNION GIRL (2022)

While returning from a nightclub having taken drugs, new girl in town and her friend find a creepy doll wearing a communion dress...

While returning from a nightclub having taken drugs, new girl in town and her friend find a creepy doll wearing a communion dress...

From The Devil’s Backbone (2001) and [REC] (2007) to The Skin I Live In (2011) and The Platform (2019), Spain’s produced some impressive examples of horror over the last couple of decades. The Communion Girl / La Niña de la Comunión, during its best moments, recalls one of these Spanish masterpieces, The Orphanage (2007), possibly the finest ghost story of this century.

It also recalls dozens of generic movies about spooky dolls and screaming teenagers, and it’s tempting to wonder if this odd combination of profundity and cliché reflects the different backgrounds of its director and writer. Victor Garcia, the director, is Spanish-born but has worked mostly in the US on unremarkable genre fare including Hellraiser: Revelations (2011) and The Damned (2013); while screenwriter Guillem Clua co-wrote the exceptionally smart God’s Crooked Lines (2022) as well as two episodes of the intelligent, multi-layered TV series The Innocent, based on Harlan Coben’s novel.

Certainly, it initially seems The Communion Girl is going to rely on shopworn elements. “My doll is lost… her skin will be rotten by now” is almost the opening line, spoken by Sonia (Claudia Rirera). Clearly the victim of trauma, she also talks of a girl who “takes me to horrible places” before the film skips four years ahead to 1987 and a first-communion service in a small Spanish town.

The dialogue here quickly stacks up further blatant opportunities for horror: a slaughterhouse, some ruins where the local children play, and more dolls. It’s also here we meet the two central characters—teenage Sara (Carla Campra) and her friend Rebe (Aina Quiñones)—as well as Sara’s younger sister Judit (Olimpia Roch). More unsettlingly, after the bored teens have left the church service, The Communion Girl introduces a distraught woman called Remedios (Anna Alarcón) who creates a scene in the town square, insisting her daughter has gone missing before she is ushered away.

This character will become important much later, but for now the story focuses on Sara and Rebe. They go to a disco in a nearby town, but their cab driver abandons them, so they set out to walk back. (We’re already getting the sense that, while Rebe’s more self-consciously rebellious, Sara may be the more genuinely adventurous of the two).

On the way, they’re picked up by Chivo (Carlos Oviedo)—a young man who clearly has ideas beyond taking them home, and may not take no for an answer—and his less aggressive friend Pedro (Marc Soler), who like the woman in the square isn’t given much attention by the film when he first appears but will grow in significance.

As they drive through the night, a little girl dressed in white crosses the dark road (you just knew that was going to happen, didn’t you?) and the four get out of their car to investigate. Soon they find a hanged dog—and, guess what, a doll…

The dog is a peculiar touch of no obvious relevance to anything else, though it’s perhaps there to signal the alienness of the area’s culture to Sara, a newcomer to the town. Another character mentions that some locals hang hunting dogs, a loathsome practice in some parts of Spain, and there’s indeed a sense throughout The Communion Girl that some people know more than they’re letting on.

Even more bizarrely, the doll itself is actually rather pointless too. Until a final-second twist which adds nothing to the movie (if anything detracting from the power of what you thought was the ending), it has no significant role to play in the plot… which would work just as well without it and isn’t even seen much.

Maybe they had to write in a doll for the sake of the marketing? So Sara, of course, takes the doll home with her, as one would any filthy old toy you found next to a dead dog in a forest… and much of the rest of the movie you can imagine from here.

Not all of it, though. The horror elements of the story that unfold after this lengthy set-up are predictable even if they’re often well-handled (when a character fleeing a ghost gets into a car, you know as they drive off that they’re not going to be alone), but The Communion Girl also takes more time than many spooky-doll movies to explore wider and more human dimensions.

It touches on the less attractive aspects of small-town life—the way that newcomers or the different can find it difficult to fit in—and pays quite a bit of attention to relationships within families, particularly those of parents to children. (These of course reflect humans’ relationships with dolls as mock infants). Some of its most successful scenes arise from this rather than the horror.

No individual actor really stands out, with the exception of Quiñones as Rebe, and that’s largely because her character is trying to be different from everyone else. But nearly all of the cast are convincing and none of them come across as one-dimensional. Along with those already mentioned, these include Victor Solé and Maria Molins as Sara’s conservative parents, Mercè Llorens as Sara’s snobbish Aunt Teresa (putdowns by her and to her are the wittiest thing in the script), Manel Barceló as the town’s no-nonsense priest, Daniel Rived as a connection between the opening scene and the main, later story, and Jacob Torres as Rebe’s abusive, alcoholic father. A shot of her snuggled up against his comatose form, desperate for his affection despite his awful behaviour toward her, is among the most striking and powerful things in the film.

Cinematographer José Luis Bernal conjures up an effective range of moods, from unearthly woods shot in red and grey/green, to the more reassuring yellow light of the nighttime town, to the black mausoleum-like atmosphere of Remedios’s home. Some rapid montages provide contrast to the generally slow pace, and Marc Timón contributes a traditional, full-textured orchestral score pleasingly almost devoid of modern horror banalities. Equally refreshing, the 1980s period isn’t overused. Only references to pre-Euro currency and the absence of mobile phones give it away.

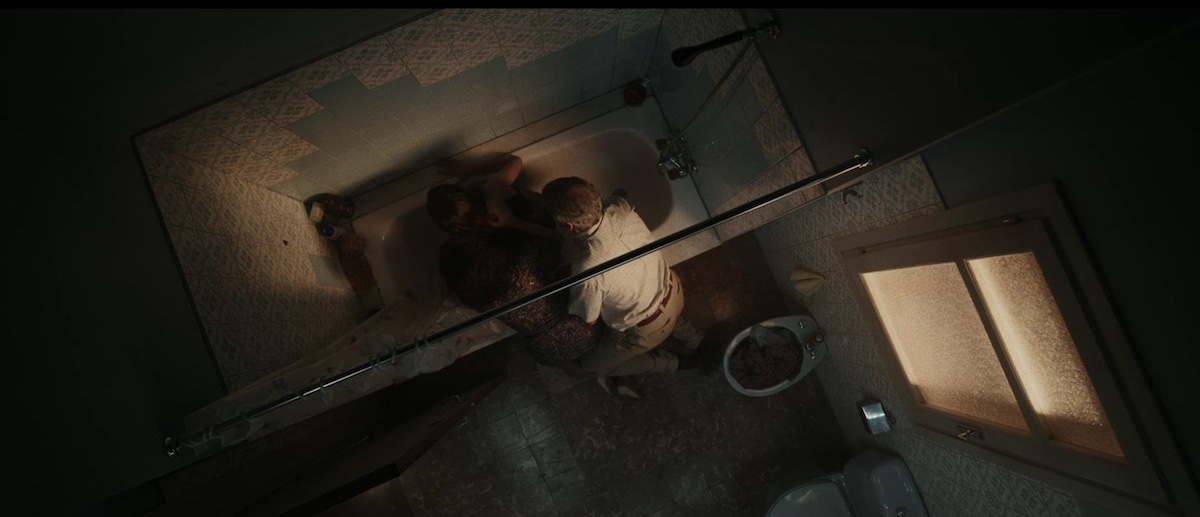

As for the horror itself, The Communion Girl isn’t scary (or particularly violent). Its appeal lies more in seeing what the central characters figure out, and how they’ll act in response. But the poltergeist-like activity that follows Sara taking the doll home is well-staged, almost thrillingly kinetic at moments, with the first of two bathroom scenes especially tense. It may have helped that Garcia, the director, has a background in effects.

By the end, there’s some full-on grotesquerie that has only been briefly glimpsed before, but the main mood of the climactic scene—or at least, what we think is the climactic scene before that silly closing twist—is sadness. And it’s here, as well as with its interest in family, that The Communion Girl most resembles The Orphanage.

It doesn’t, though, come close to reaching the heights of that movie or other great Spanish horror. The unnecessary doll is symbolic of the way that, although The Communion Girl does more than many similar movies to create interesting characters and relationships, the filmmakers still apparently feel they have to prioritise horror conventions. Indeed, it doesn’t even do as much as it could with Sara’s and Rebe’s fears.

The result is a film that’s skilfully made, always watchable, and at times feels like it just could flower into something more complex and wider-ranging than a genre exercise… but never quite manages to.

SPAIN | 2022 | 98 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | SPANISH

director: Victor Garcia.

writer: Guillem Clua.

starring: Carla Campra, Aina Quiñones, Marc Soler & Carlos Oviedo.