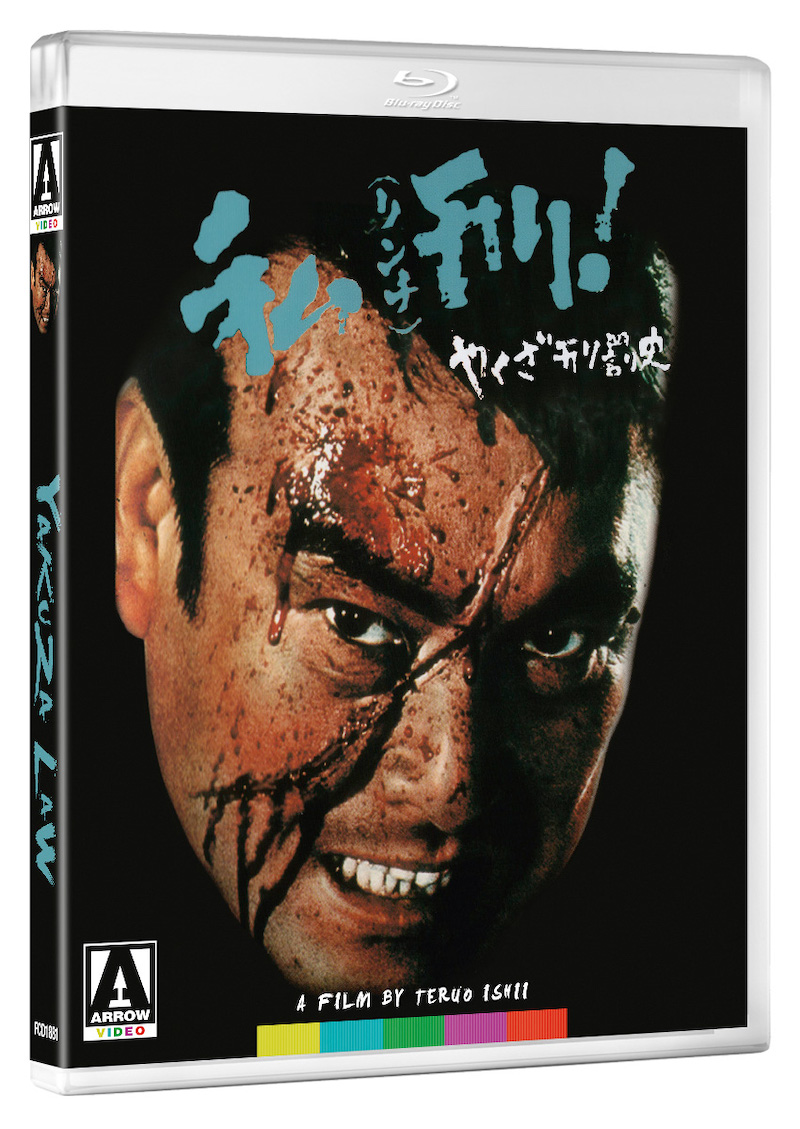

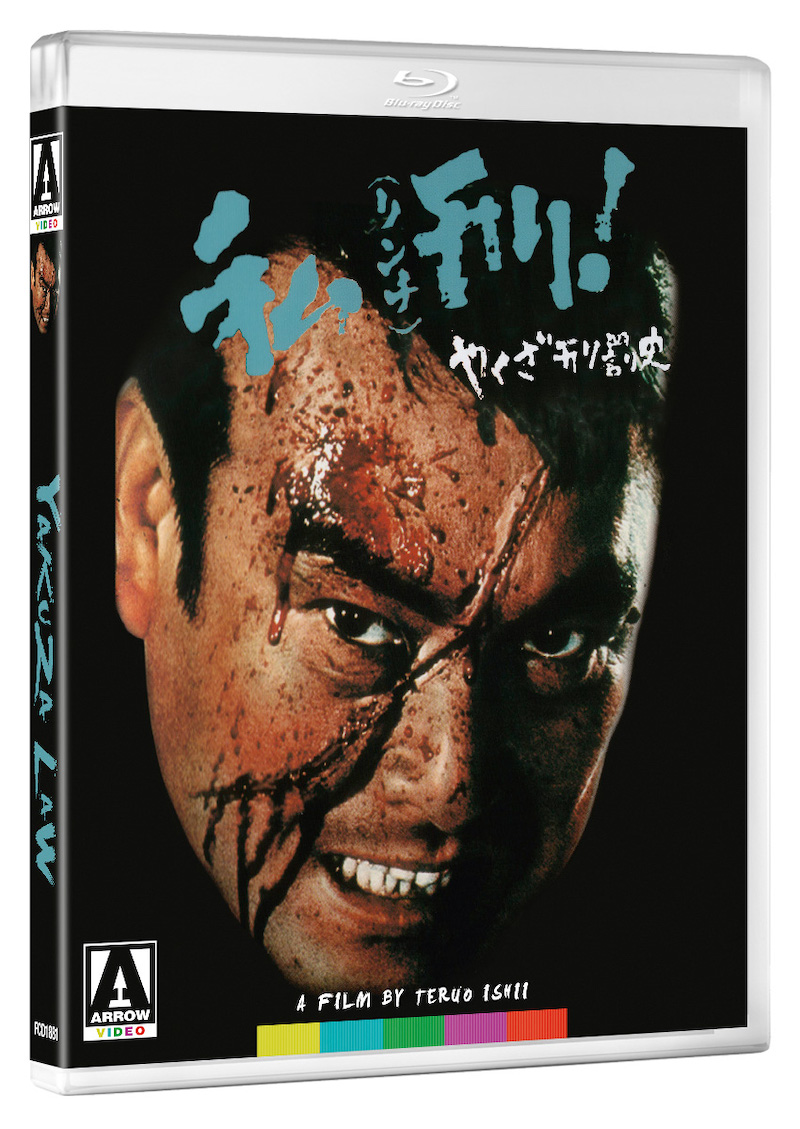

YAKUZA LAW (1969)

A story of yakuza lynching during the Edo, Taisho, and Showa periods.

A story of yakuza lynching during the Edo, Taisho, and Showa periods.

His name means little to most western audiences, but if you were living in Japan during the late-1960s and early-’70s, you likely saw quite a bit of Teruo Ishii at your local cinema. In 1969 alone, Ishii released seven films for Toei Company, the studio that rose to fame with TV shows like Super Sentai (repurposed in the US as Mighty Morphin’ Powers Rangers). The two wings of Toei were animation and exploitation, and Ishii fell firmly into the latter category. His films defy genres and upset stomachs like few others from that period, pioneering a transgressive style halfway between exploitation horror and arty erotic drama.

Scattered throughout his filmography, however, are decidedly less subtle films—films that don’t toy with repulsion but instead rub it in your face. Yakuza Law is one of those. Originally translated as Yakuza’s Law: Lynching in spite of an almost complete absence of any lynching, the film is on the surface a study of the strict code of the Yakuza throughout history and what happens when that code is broken.

Divided into three segments, we see the inner-workings of the Japanese organized crime syndicate in the Edo, Taisho, and Showa period. That’s roughly the 1700s, early-1900s, and the 1960s. Each time, we’re told a law of the Yakuza in narration and then are shown a story in which that law is violated, and how that transgression is punished. For all its careful period detail and casting of some then-big names in Japanese exploitation cinema, the real purpose of the film is to revel in the most extreme gore allowed in Japanese cinemas at the time.

I know what you’re thinking: how violent could a film from 1969 really be? The answer is more violent than you’d imagine. Surely nobody is trapped in an industrial car crusher? Or dragged by a rope from a helicopter? Well, that’s where you’re wrong. All of this happens and more, with everything shown so you don’t miss a second of the mutilations Ishii has in store for these men. The degree of brutality in the film is genuinely shocking, not the least of which because Yakuza Law turns 50 this year. The gore is OTT but, more importantly, it’s completely devoid of camp value. It looks real, so chuckling over its excessiveness doesn’t last long because it’s played so straight.

When you compare the drama to the gore, it’s clear where Ishii’s passion lies. All of the film’s most engaging scenes are the gruesome ones. That’s more or less a no-brainer considering this is a film about violence, but it’s both a blessing and a curse. The blessing is how engaging the aforementioned scenes are, but the downside is everything else feels terribly tame by comparison. The more dramatic scenes, which make up a majority of the film, have a certain luridness in how they all deal with extramarital affairs, murder, and gangsters, but they’re ultimately only a means to an end. It’s no secret why someone goes to see a brutal movie like this.

Fortunately, each successive segment focuses a bit more on the violence and a little less time on the plot. The third and final segment is undoubtedly where the film peaks, as it features almost constant action and some of the most gruesome sequences. The previously mentioned car crusher scene is one for the ages—but keep an eye out for some spectacularly dated and psychedelic VFX of the unfortunate victim being squished to oblivion.

Having the segments move from least to most interesting creates a sense of payoff by the time the movie’s over, but it also makes Yakuza Law a bit of a slog. One has to sit through some of the tedium of the first two stories. The film does get off to a great star, with opening credits shown over a montage of nauseating deaths (involving power drills and eyeball burnings), but when the Edo-era plotline kicks in we’re brought back to passable period drama territory.

The most striking thing about a film like this, and Teruo Ishii’s early filmography in general, is knowing it was produced by a studio as big as Toei and, therefore, had significant resources at its disposable. Aside from the obvious VFX budget, there are high-quality sets, excellent costumes, and impressive cinematography that are all well beyond the standard for a film like this. Inconsistent as it may be, there’s something worth celebrating and witnessing in the sheer strangeness of Ishii’s film: an unrepentant blood bath with blockbuster production values. If nothing else, it’s a fascinating monument to the glorious, messy, stomach-churning dawn of the modern exploitation flick. A genre that would only get more bonkers and horrific in the decades to come.

writer & director: Teruo Ishii.

starring: Minoru Oki, Teruo Yoshida, Bunta Sugawara, Masumi Tachibana, Yukie Kagawa & Yumiko Katayama