IVAN’S CHILDHOOD (1962)

In WWII, 12-year-old orphan Ivan Bondarev works for the Soviet army as a scout behind German lines and strikes a friendship with three sympathetic Russian officers.

In WWII, 12-year-old orphan Ivan Bondarev works for the Soviet army as a scout behind German lines and strikes a friendship with three sympathetic Russian officers.

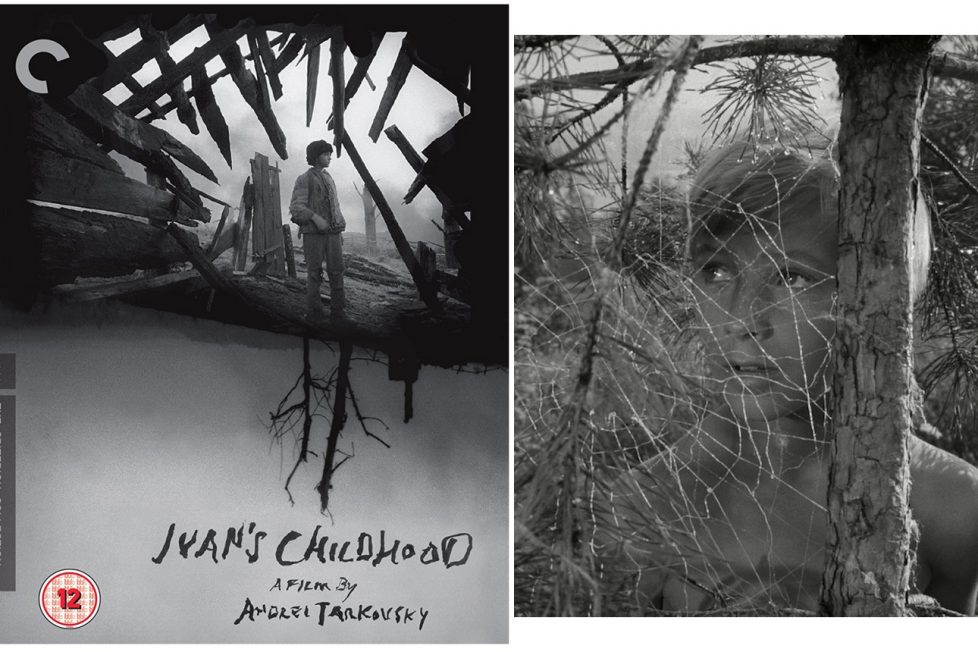

The first image we see is Ivan as a young boy, framed by a spider’s web. One may think the web looks a bit fake, like a child’s drawing, and it’s not long until we realise we’re looking through a window into Ivan’s idyllic dreamworld. Ivan runs through sun-bleached meadows and chases butterflies, becoming as weightless as one, and we fly with him into the tree canopy, then down to a beach where a woman carries a bucket of water from a well. He cools his face in the pail of water and, looking up at his mother, says, “mama, there’s a cuckoo.”

Of course, the call of a cuckoo is a sign of spring and impending summer, but at the same time we know that it spells doom for many nestlings. His mother smiles and raises an arm to brush stray strands of hair from her eyes and the dream ends. Ivan awakes in a burnt-out windmill and makes his way across a desolate landscape under drifting clouds of black smoke. The expressive, low and wide angle shots make it clear his reality is now more like a nightmare. What is this young boy doing all alone, ducking under barbed wire and trudging through swamps at night, eerily lit by the light of distant flares that fizzle out in the dark water? It’s like a war zone!

The opening sequences are fine examples of the cinematic, visual poetry that Tarkovsky became known for. It seems Tarkovsky had already established much of his visual language and set out many of his recurring themes in the first few minutes of his debut feature film… and it’s not a case of wowing us with an opener that fully exploits the capabilities of celluloid, the whole film is one of the richest cinematic experiences one could hope for, perhaps only out-done by every other Tarkovsky film!

Ivan’s Childhood is based on Vladimir Bogomolov’s acclaimed 1957 short story, simply titled Ivan, a bleak meditation on the devastation wrought by war at a personal level. Mikhail Papava, the first writer to attempt a screen adaptation, changed the ending to make it more heroic and up-beat, retitling it Second Life. In his version, Ivan survives the war. Bogomolov, exercising his moral rights as the author, didn’t approve the changes and the original tragic conclusion was restored.

After a rewrite, the script was finally approved by the state committee for film and Mosfilm assigned the project to Eduard Abalov. Late in 1960, when the initial footage was reviewed, it was rejected on grounds of poor quality and Eduard Abalov was fired as director. (He did go on to direct a two or three small films and had marginally better luck as an actor.) Although approved and ready to go, the Ivan project was shelved…

Andrei Tarkovsky, in his early-20s and a recent graduate from the State Institute of Cinematography (VGIK), heard about the dormant project from Vadim Yusov, the cinematographer he’d worked with on his short diploma film The Steamroller and the Violin (1961). He applied to replace Abalov and was accepted on the strength of his student show-reel.

In June 1961, with Tarkovsky at the directorial helm, production resumed with location filming along the Dnieper River in the Ukraine, near Kaniv—smack in the middle of a fiercely contested territory. The area was remembered in the Russian psyche for the 1918 Battle of Kaniv, which ended in siege, and as the site of a tragic defeat during the Second World War, when a paratrooper division was dropped behind enemy lines but failed to slow the Nazi advance… Tarkovsky must have thought it resonated well with the script’s subject matter.

Tarkovsky has built-up a professional relationship with Vadim Yusov and brought him back as cinematographer, who does an amazing job. Yuskov shared Tarkovsky’s desire to imbue film with meaning, not solely through dialogue and story, but through landscape and pure imagery. The starkly charred ruins, through which Ivan wanders for the first part, create an atmosphere almost as expressionistic as the dream sequences.

Yusov wasn’t the only contact from his diploma production that Tarkovsky called-in. Andrei Konchalovsky, a fellow VGIK graduate of 1961, who co-wrote The Steamroller and the Violin, lent a hand in further adapting the script into what would become Ivan’s Childhood, and also appears in a bit-part. Konchalovsky had used Nikolai Burlyayev as the lead in his own diploma short,The Boy and the Pigeon (1961) and introduced the young actor to Tarkovsky who subsequently cast him as Ivan. The music for The Steamroller and the Violin, integral to its plot, was composed by Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov who also returns to contribute the haunting score to Ivan’s Childhood.

Tarkovsky would again work with all four on his second film, Andrei Rublev (1966). Konchalovsky went on to forge a long, successful career of his own, as a writer and director. Burlyayev went on to act in more than 50 films. Yusov would work with Tarkovsky again on Solaris (1972) and photograph around 20 films over the next four decades. Ovchinnikov also scored more than two dozen films over a career that continued into the mid-1980s.

Burlyayev turns in an utterly convincing and emotive performance as the 12-year-old Ivan who, after surviving behind enemy lines, manages to make his way back to a Russian camp. There, two officers, Kholin (Valentin Zubkov) and Galtsev (Evgeny Zharikov) along with a young army nurse, Masha (Valentina Malyavina) become a substitute, if dysfunctional, family unit. Initially, they want to send Ivan off to the relative safety of military school, but he refuses, choosing to stay on at the Eastern Front as their scout.

Through dreams and flashbacks, it becomes clear that Ivan is now driven by a quest for revenge. This totally understandable reaction, to try to deal with or derail his internal anguish (at the loss of his family, his home, his community, his entire village) is but a fractal of what drives many a war. One generation seeking retribution for abuses suffered by their forebears. Children of victims holding a grudge against the children of perpetrators and so perpetuating the cycle of conflict. Tarkovsky introduced Ivan’s dreams of childhood, because he thought that purity of innocence was the antithesis to the corruption of war. Memories of childhood were to become a recurring theme in the films of Tarkovsky.

The flashbacks were not in the original treatment and draw upon Tarkovsky’s own idyllic childhood as their source material. This introduction of potent visual poetics, that could not have been expressed in the approved scripts, was an important lesson for Tarkovsky. He incorporated this innovation into a working method that enabled artistic freedom, within the constraints of the Russian Film Industry.

Tarkovsky manages to cleverly circumnavigate censorship, and therefore avoid compromise, through this uniquely clever approach. He would submit his scripts for approval, then continually re-write and adapt during almost every stage of production: changing and adding dialogue, using different locations, writing whole new sequences as he went along. Then after the footage had been reviewed and approved, albeit by film officials who could no longer follow exactly what changes had been made, he would then begin the long editing process. Again, he took this opportunity to change things around and build a film that may well have been very different from the initial script he had submitted.

Known to cut and re-cut, he is said to have completed several fully finished and different versions of his autobiographical opus Mirror (1975). When his final films were then viewed by the state censors, their poetic ambiguity was deliberated, sometimes for years, and more than once his films had their release schedules pushed back indefinitely but were never officially banned. To put this in some sort of context, Sergei Parajanov, his only contemporary of similar stature in the Soviet film scene of the 1960s, suffered far more for his art, being persecuted and imprisoned several times because he refused to compromise on content. Parajanov would later cite Tarkovsky as a huge influence and inspiration.

Although freedom of expression was by no means celebrated, cinema was enjoying a relaxation of control and censorship in what is now referred to as the Khrushchev Thaw; a period when Nikita Khrushchev deliberately set about dismantling the repressive state structures imposed under Stalin. This meant that young film graduates, who’d not been given a chance under the restrictions of the totalitarian regime, were suddenly finding increased opportunity as the film industry recovered and more and more films went into production. It also made it possible to approach difficult subjects, such as the war, from different perspectives.

Before this, a film like Ivan’s Childhood would not have been possible, because any film dealing with the war had to portray the Russians as classically heroic and victorious, showing the glorious State only in the best light. A small personal story, ending in realistic tragedy, would never have been approved, and this makes Ivan’s Childhood historically important as well as artistically impressive, placing Tarkovsky at the crest of a New Wave of Russian filmmakers.

Perhaps because the film was so different from most of its precursors, it captured the nation’s imagination and did incredibly well in their domestic cinemas. It swiftly gained international acclaim, too, winning the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, and the Golden Gate Award at the San Francisco International Film Festival.

At the time, philosopher, novelist and playwright, Jean-Paul Sartre, recognised the film’s freshness and the profound impact it would have, writing “it is not the Golden Lion that will go on to be the true reward for Tarkovsky but the polemical interest raised by his film with those who are struggling together for liberation of man against war.”

Tarkovsky’s greatest achievement with Ivan’s Childhood is managing to create something with so many memorable and potently poetic images out of material that could have, so easily, become too dark and depressing. All of Tarkovsky’s oeuvre are beautiful to behold, every frame he ever shot could be isolated and presented alongside the very best photography, and each of his films contain moments of profound poetic genius. Although Ivan’s Childhood is his debut feature film, it remains no exception.

It’s probably the most traditional of Tarkovsky’s work in terms of the camerawork and especially the pacing—which is relatively swift compared to his later, more ponderous productions. This might make it a good starting point for anyone new to Tarkovsky, though it is also a harrowing experience, one of the most affecting films about childhood and its destruction by war. Although ultimately tragic, it is made bearable by unexpected moments of breath-taking beauty. The final shots of Ivan, reunited with his little sister and mother on a glittering shoreline are poignant and heart-rending.

The beautiful monochrome photography looks great on this new digitally restored high-definition print from the Criterion Collection and an uncompressed monaural soundtrack makes the most of the sound design and music by Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov. There is no commentary—to be fair, the film would probably be difficult to watch with such an intrusion, but we do get an informative appreciation of the film by Vida T. Johnson, co-author of The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky: A Visual Fugue. The short interviews with cinematographer Vadim Yusov and actor Nikolai Burlyaev are also most welcome and their reminiscences give us a lot of background.

director: Andrei Tarkovsky.

writers: Vladimir Bogomolov & Mikhail Papava.

starring: Nikolai Burlyaev, Valentin Zubkov, Evgeny Zharikov, Stepan Krylov & Nikolai Grinko.