THE FINAL PROGRAMME (1973)

A trio of scientists plan to create a self-replicating, immortal, hermaphrodite using the Final Programme developed by a dead, Nobel Prize-winning scientist.

A trio of scientists plan to create a self-replicating, immortal, hermaphrodite using the Final Programme developed by a dead, Nobel Prize-winning scientist.

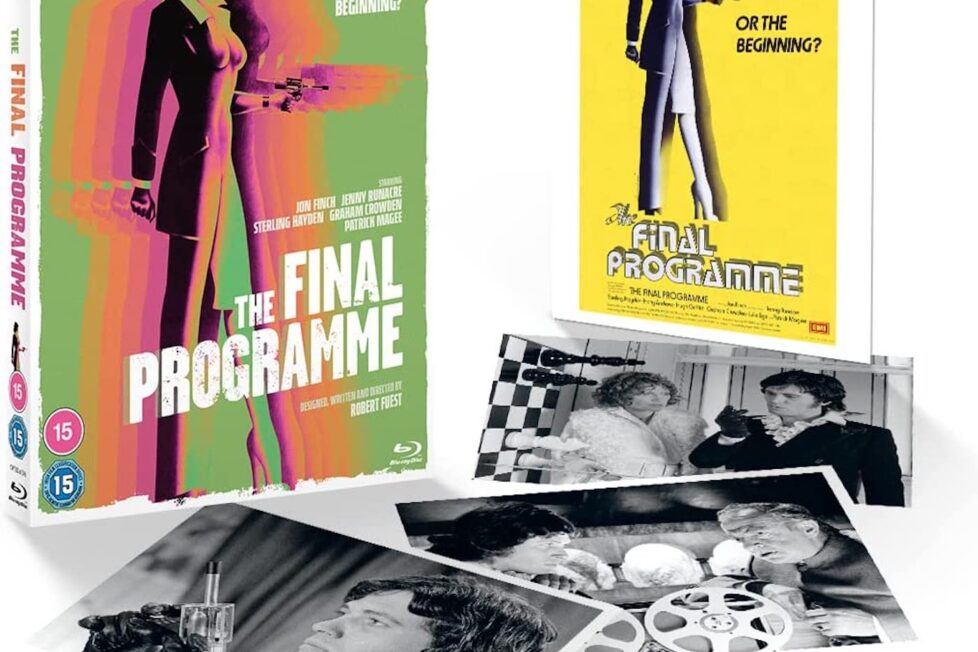

With The Final Programme, Robert Fuest proved himself the only director brave enough to adapt a novel by Michael Moorcock for the screen. The results are as entertaining and audaciously bonkers as one might imagine. If you’re looking for something that blends the frenetic finale of The Prisoner (1967-68) with the socio-satire of A Clockwork Orange (1971), and could just about be taken as a prequel to the camp dystopia of Zardoz (1974), then this restored print on Blu-ray from Studio Canal will make you happy.

Despite the title, The Final Programme was the first in what became a quartet of freewheeling science-fiction novels featuring hero-cum-antihero Jerry Cornelius. It was first published in 1968 with two sequels, A Cure for Cancer and The English Assassin, following in quick succession by the time the film was in production. Then there was a five-year hiatus before the fourth and final instalment, The Condition of Muzak, in 1977. Across the four stories, Jerry Cornelius is reincarnated into different scenarios that aren’t directly linked but all resonate with each other and share a cast of core characters. Cornelius is sometimes described as a secret agent or superhero, though doesn’t quite match either trope. ‘He’ is gender-fluid, maybe hermaphrodite, possibly transspecies, and able to survive death by jumping realities.

Michael Moorcock is credited as originating the concept of a multiverse providing a backdrop for an array of entangled narratives, particularly stories involving Jerry Cornelius and Elric of Melniboné. Apparently, The Final Programme is a loose re-telling of several earlier stories featuring the sickly, sword-empowered sorcerer, Elric and Cornelius can easily be interpreted as an alternative expression of Moorcock’s ‘eternal champion’ concept.

Initially, Robert Fuest hoped to adapt the Jerry Cornelius books into a four-film franchise but those hopes were dashed due to poor ticket sales and dire distribution—the international release was delayed and, for the US, it was trimmed and re-titled The Last Days of Man on Earth. Also, Moorcock was unhappy with the final product. So, although the character has been reborn many times through graphic novels and song lyrics, The Final Programme remains their only big-screen incarnation.

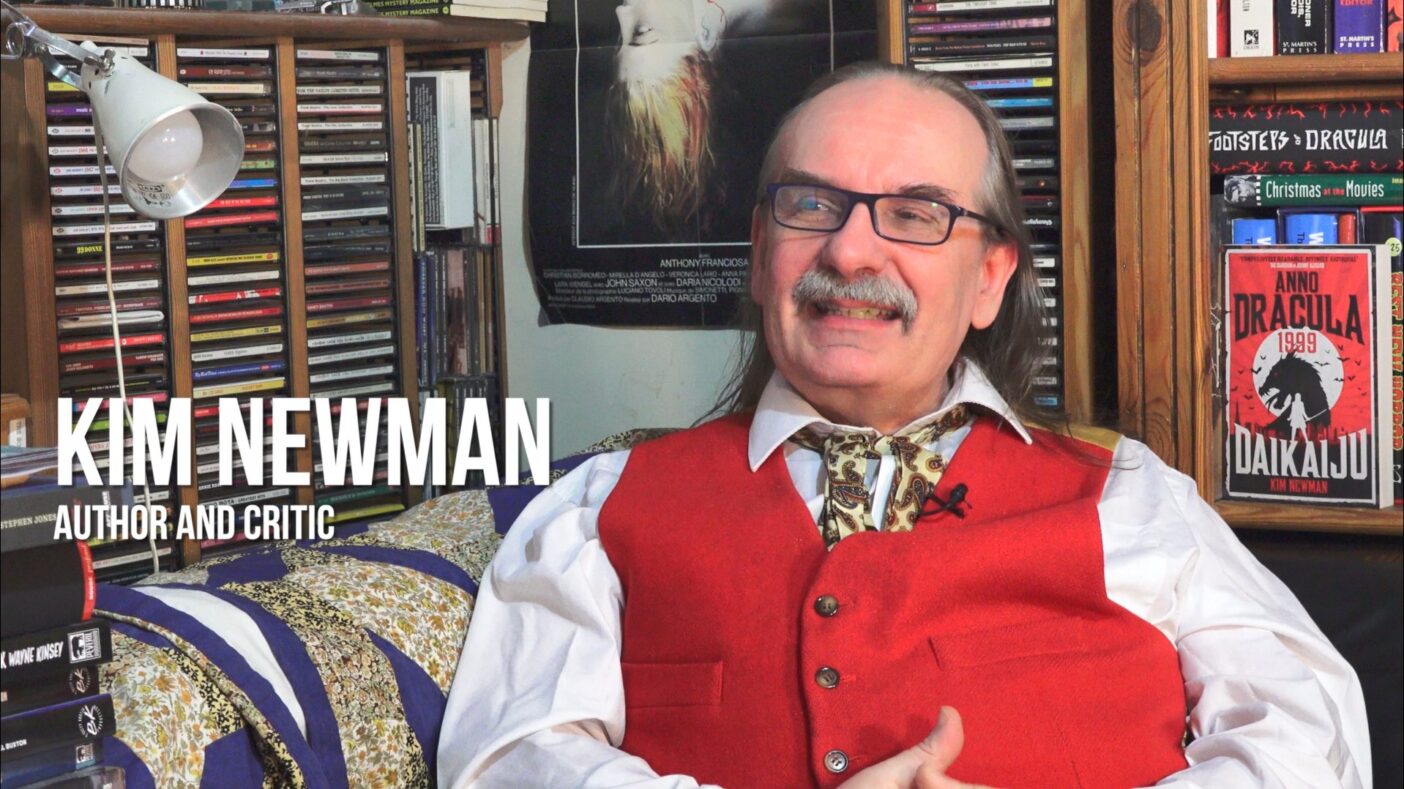

In hindsight, the film seems so deeply embedded in the zeitgeist of its times that it’s hard to see how it failed, but perhaps it was simply too stylistically shocking or conceptually challenging for mainstream audiences back then. However, publicity highlighting its X-rating earned enough notoriety to keep it on the screens of certain cinemas as it attracted a cult following while sci-fi slowly gained momentum throughout the 1970s. Times have changed and its UK Blu-ray debut now carries a 15-certificate.

2023 marks the film’s 50th anniversary, so there’s that added retro appeal but surprisingly, and rather sadly, the themes remain just as relevant as we consider the possibilities of our ‘post-human’ existence under the threat of a self-inflicted extinction. Its narrative style seems vital and ‘modern’, and there’s never a moment that’s not interesting but the excess of ideas can’t all be satisfyingly explored. That said, the central narrative is pretty uncluttered, if a touch outlandish.

The opening scenes of rugged men in fur jerkins carrying wooden beams and a coffin across desolate high plains may appear more like a spaghetti western than experimental science-fiction as they build a funerary pyre. The setting is Lapland—hence the pyre because often the ground is too frozen to dig a grave—but the sequence was filmed in Almeria, Spain, a location used in so many Euro-westerns including Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy.

Jerry Cornelius (Jon Finch) joins the rag-tag procession and watches from a distance as a hooded priest says a few words and it becomes apparent the departed is Jerry’s father, a Nobel Prize-winning ‘bio-physicist’ who was working on a programme that could be encoded into the human bio-computer at a molecular level that would create a self-healing, self-replicating, all-knowing, potentially immortal humanoid superbeing. He believed this would be the only way our species could survive the post-apocalyptic global collapse. He referred to this code as the ‘final programme’ and quite predictably, there are various interested parties that would love to get their hands on it.

Michael Moorcock’s central premise is a response to what were new concepts in psychology laid out by John Lilly in his seminal 1968 work Programming and Metaprogramming in the Human Biocomputer: Theory and Experiments, which proposes a systematic approach to understanding and talking about the correlation between physiology and consciousness—a hot topic at the time. In his fiction, Moorcock takes serious theories into the realms of sci-fi by suggesting that both our physical and mental make-up could be altered by the insertion of an actual dataset. But what would that look like and how would one insert such a programme into a living person?

Jerry Cornelius knows that if his father had succeeded in producing that ‘final programme’ it would be stashed at the family seat, a huge futuristic fortress of a manor house. So, to ensure it never falls into the wrong hands, he decides to blow the whole place up and sets about scoring some napalm for the job from a shady arms dealer over a game of pinball.

He enlists the help of John (Harry Andrews) the faithful family butler who informs him that he must first rescue his fragile sister, Catherine (Sarah Douglas), from the house where his bad brother, Frank (Derrick O’Connor), is keeping her captive and heavily sedated with a cocktail of drugs. Before Jerry can return to this dysfunctional, Edgar Allan Poe-inspired dynamic with incestuous overtones, his curiosity is captured by Miss Brunner (Jenny Runacre). This is the earliest substantial role for the actress after a run of significant bit parts that followed her debut in Goodbye Mr Chips (1969). Brunner is a ‘programmer’ representing a group of scientists who built the apparatus necessary to complete the work Jerry’s father began and require a living Cornelius to bypass the smart building’s defences, which Frank has activated.

Production for The Final Programme ran consecutive to Robert Fuest’s Dr Phibes films and indeed Anton Phibes would be at home in the spacious Deco sets designed by Fuest with support from Philip Harrison, who’d assisted him on Wuthering Heights (1970), and a young Roger Christian, who would later work on Star Wars (1977) and make his own directorial debut with The Sender (1982). The three had first worked together on Fuest’s sophomore feature And Soon the Darkness (1970).

The booby-traps within chez Cornelius could also pass as the work of Phibes—mazes fitted with trance-inducing light effects, colourful paralyzing gasses, and a door to the inner sanctum fitted with an over-sized chess set which must be moved into checkmate to unlock. Move the wrong piece and a spike springs out, which just might be loaded with narcotics. It’d be an understatement to say not everything goes to plan! After a suitably psychedelic sequence, the psychotic Frank escapes with the programme…

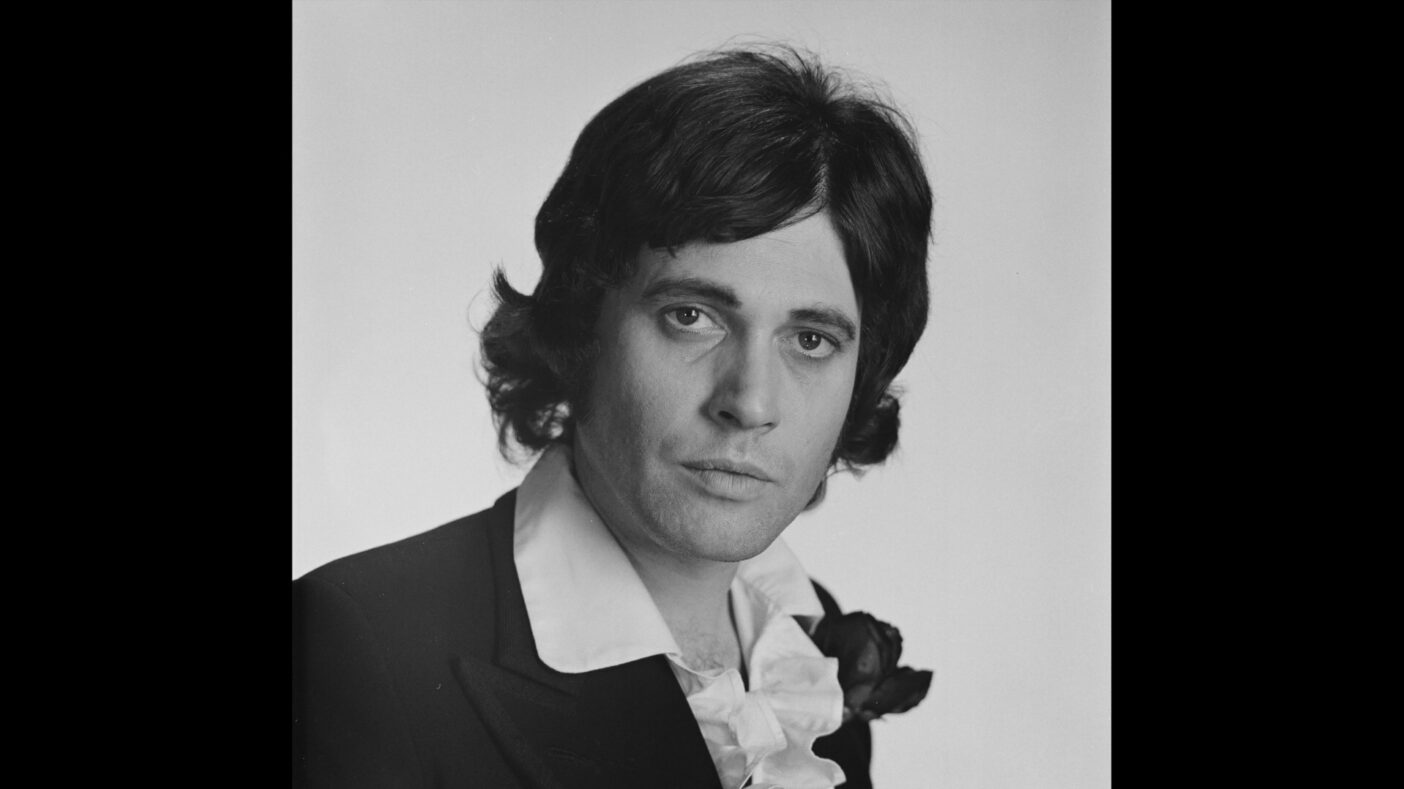

Jon Finch was a Hammer Films regular who’d just become an actor of note since playing the lead in Roman Polanski’s Macbeth (1971). At first, his Cornelius seems suave and knowing but is gradually revealed as ineffectual and beleaguered by ennui, self-medicating with whiskey and choccy biccies. We also gather that far from being in control, he’s being swept along solely by curiosity and for much of the time remains unaware that he’s being manipulated, groomed for a destiny he may prefer to avoid. We get the first big clue that he’s been set up as he recuperates in a nursing home that’s suspiciously understaffed and looks rather like a stage set. In a way, his misguided bravado throughout is similar to Edward Woodward’s willing victim in The Wicker Man (1973), released the same year.

Here, Jerry Cornelius comes across as an angry, off-the-rails, Jason King type and maybe Department S (1969-70) was an influence as it too starred a dangerously suave dandy and female computer scientist. As with his Phibes duology, Fuest is channelling that era of British television eccentricity, drawing on his experience designing and directing several of the more bizarre episodes of The Avengers (1961-69).

One can’t avoid comparing the fashion sense of Jerry Cornelius with contemporaneous Doctor Who—John Perwtee as the Third Doctor in similar frock-coats, velvet jackets, and ruffled shirts. Though, with his penchant for black nail varnish and a black rose buttonhole, there are also hints of the deranged, proto-gothic Master. In turn, this borrows from, and feeds back into, the fashion of the day as sixties psychedelia morphed into Glam Rock with the first darker inklings of nascent ‘heavy metal’. Jerry was styled by Tommy Nutter, the go-to trendy tailor who was dressing the likes of Mick Jagger and Elton John, and famously provided suits for three of the ‘Fab Four’ as seen on the zebra-crossing cover photo for their 1969 album, Abbey Road.

While we’re talking about music, Michael Moorcock was collaborating with a psychedelic rock band called Hawkwind at the time. His fiction had already inspired some of their songs, and he was developing album concepts and contributing original lyrics. Being a musician himself and an occasional member of their live line-up, he suggested that they provide the score. However, Robert Fuest didn’t take to that idea, instead hiring Beaver and Krause, the pioneering electro-music duo who popularised the new Moog synthesizer. Indeed, they became official sales reps for Robert Moog and sold the new instruments to many experimental bands of the day including The Byrds, The Doors, and The Beatles. Fuest wanted their ground-breaking, ‘futuristic’ sound to counterpoint a jazz-oriented soundtrack and balance the organic baritone sax tones of Gerry Mulligan who famously played on the 1957 Birth of the Cool sessions with Miles Davis. However, Fuest did use the members of Hawkwind as extras and apparently–if one fancies playing ‘Where’s Lemmy?’—they can be spotted in the arcade scene.

So, the chase is on as Jerry and Miss Brunner pursue Frank across a decadent dystopia that still has vestiges of ‘normality’ despite major cities becoming nothing more than vast swathes of ‘white ash’. Some cars are still on the road, including Jerry’s 1937 McLaughlin-Buick, though Trafalgar Square is a scrapyard piled high with so many that aren’t. The trains still run and international flights are possible, provided one’s rich enough to buy an aircraft from rogue military operations like the one led by a bewildered Major Wrongway Lindbergh (Sterling Hayden).

Here, the veteran actor sports a Castro beard and is channelling his earlier incarnation as the insane Brigadier General Ripper in Dr Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), adding to the Kubrickian mood. Although it was the tail-end of a long career, he was fresh from filming Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye (1973) and still had more than a dozen screen appearances left including reprising Captain McCluskey from The Godfather (1972) for The Godfather Saga (1977) miniseries. Though he remains best known as the star of several classic westerns from the 1940s and ’50s including Nicholas Ray’s highly influential Johnny Guitar (1954).

Undeniably, there’s a palpable influence from A Clockwork Orange in the irreverent glee with which Fuest sends up the British establishment. The presence of Patrick Magee is perhaps a knowing nod, though the actor was already a cult favourite before he worked with Kubrick, having appeared in Francis Ford Coppola’s Dementia 13 (1963), Roger Corman’s The Masque of the Red Death (1964) as well as a clutch of Amicus anthologies including Tales from the Crypt (1972) and Asylum (1972). Here, he’s joined by George Coulouris, another hard-working character actor who also took a supporting role in A Clockwork Orange.

At the time, much was made of the presence of Julie Ege as Jerry’s glamorous paramour. Her name’s even given second billing to Jon Finch on some promotional material although she only appears in the amusement arcade scene, where nuns test their faith with one-armed bandits. This was largely due to her recent fame as a ‘Bond girl’ after appearing in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969) and her lead role in The Creatures the World Forgot (1971) in which she shows some skin in an attempt to rival Raquel Welch as a fur bikini model.

There’s a certain frisson between Jerry and Brunner but she slowly reveals herself to be a vampiric pansexual capable of assimilating the flesh of her lovers, presumably something she’d been doing for a while in order to gather a ‘critical mass’ of DNA samples. Maybe, that thread would make more sense to those who read the novel as it’s never clear in the movie but makes for some interesting moments and neatly disposes of a few superfluous characters. Whilst on the subject, it was the sex and drugs content that earned the ‘X’ certificate and, yes, there’s some nudity here and there. But that’s either matter of fact, in alignment with 1970s free-love sensibilities, or played clumsily for laughs rather than any erotic charge. There is one uncomfortably prolonged sequence involving the butt of an overly hairy hermaphrodite ‘neanderthal’ that will certainly have the viewer chuckling. If only to cover their embarrassment…

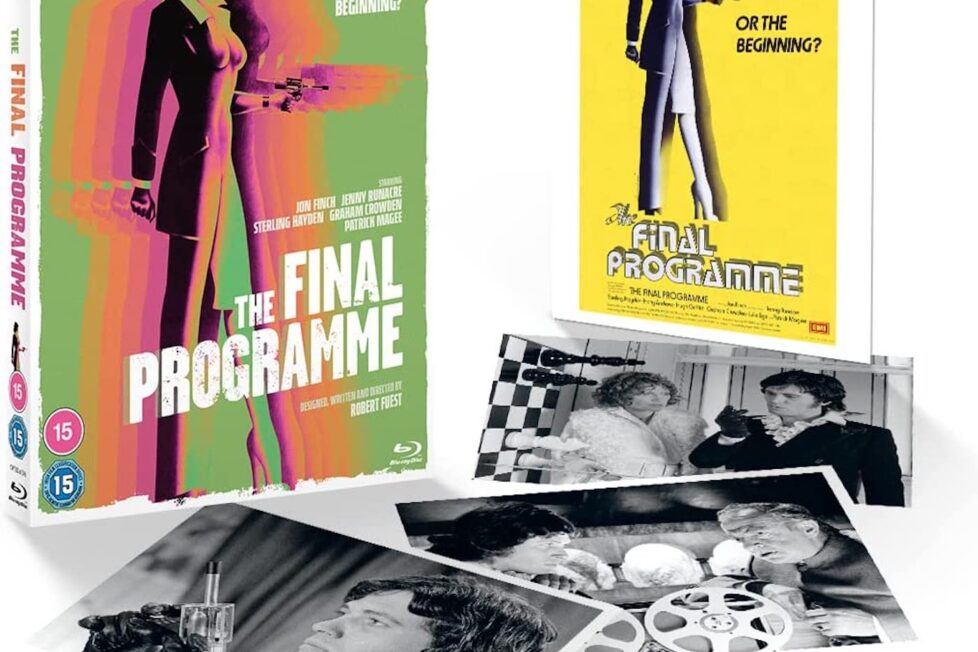

Stylistically, The Final Programme is a retro delight and, if one welcomes its mad, mind-bending satirical slant, there’s much to enjoy but it remains too dark to be funny yet too comedic to be taken seriously. Admittedly, that’s a tricky balance to strike but Fuest manages that perfectly with The Abominable Dr Phibes (1971) and, to a lesser degree, its sequel Dr Phibes Rises Again (1972). It’s essential viewing for Fuest fans and invaluable for dedicated sci-fi buffs who will track its influence throughout the genre’s more radical offerings of the era. Demon Seed (1977) tackles several common themes more successfully and some scenes in Altered States (1980), also inspired by the research experiments of John Lilly, are remarkably similar.

Though it marks a downturn in the career trajectory of Robert Fuest, Michael Moorcock has since established himself as the figurehead for what became known as British New Wave science fiction. He remains relevant with transmedia contributions such as games scenarios—one of which ended up via a circuitous route as the novel Silverheart written with Storm Constantine and published in 2000; and numerous music projects—such as writing, singing, and playing a range of instruments on the Spirits Burning 2008 album ‘Alien Injection’. The latest album from his own band The Deep Fix, titled ‘Live at the Terminal Café’, was released in 2019.

Various reincarnations and reimaginings of Jerry Cornelius have appeared in the collaborative works of several other high-profile authors including Moorcosk’s ex-wife, Hilary Bailey, and some of his contemporaries such as Brian Aldiss, M. John Harrison, Norman Spinrad, and James Sallis. More recently, he appeared in the Alan Moore graphic novel sequence, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen III: Century (2009-2012), illustrated by Kevin O’Neill. Captain Cornelius embraced his villainous vibe in Michael Moorcock’s Doctor Who novel of 2010, The Coming of the Terraphiles, and his latest Jerry Cornelius novella Pegging the President was published in 2018. That’s a whole lot of Jerry Cornelius going on and, although Michael wouldn’t agree, the best introduction for the uninitiated to the mercurial character and his multiverse of madness remains Fuest’s version of The Final Programme.

UK | 1973 | 94 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

Although it’s a challenge to provide a meaningful audio commentary, it would’ve been nice to have one from an informed authority—maybe a Michael Moorcock ‘scholar’—to point out the differences between the novel and film and discuss the subtexts, especially the ones that are glossed-over in the screen version, such as the dysfunctional incestuous triangle between the Cornelius siblings and how that relates to other incarnations of those characters in the other three books of the quartet… and perhaps shed some light on the somewhat rushed finale which I’m sure will baffle those who haven’t read the book. Apparently, Robert Fuest and Jenny Runacre recorded a commentary for a 2001 DVD release. It’s a shame this couldn’t be sourced.

director: Robert Fuest.

writer: Robert Fuest (based on the novel by Michael Moorcock).

starring: Jon Finch, Jenny Runacre, Hugh Griffith, Harry Andrews, Patrick Magee, Ronald Lacey, Graham Crowden, George Coulouris, Basil Henson, Sterling Hayden.