COLOSSUS: THE FORBIN PROJECT (1970)

Thinking it will prevent war, the US government gives an impenetrable supercomputer total control over launching nuclear missiles. But what the computer does with the power is unimaginable to its creators.

Thinking it will prevent war, the US government gives an impenetrable supercomputer total control over launching nuclear missiles. But what the computer does with the power is unimaginable to its creators.

The Forbin Project is a smart and truly seminal movie. The issues it confronts are far subtler than the central story concerning a megalomaniac computer attempting to take over the world by outsmarting the boffins who developed it. What’s kept it remarkably relevant is its prescient viewpoint, given that it was released long before the internet age.

Artificial intelligence is the future, not only for Russia, but for all humankind. It comes with enormous opportunities, but also threats that are difficult to predict. Whoever becomes the leader in this sphere will become the ruler of the world.

—Vladimir Putin, (real) President of Russia, September 2017.

Of course, made at a time when a basic payroll computer occupied a space of warehouse proportions, The Forbin Project has dated wonderfully. Now the production design offers nostalgia, with the Don Record-designed titles immediately setting the mood with their weird electronic beeps and clickety-clack noises, behind lovely close-ups of mechanical components, transistors, big spools of tape, and panels of blinking lights. This is what computers were supposed to look and sound like! At least in the 1970s.

What irrevocably dates the film has become one of its major attractions. It has a kind of hauntological appeal akin to steam-punk, only I suppose this would be analogue-punk? I think we’ve coined a new phrase for a genre that I, for one, am keen to see emerge in new movies today! The time is ripe, and this would make a great template.

The film may be ‘of its time’ but the issues it raises are just as relevant today as they were back then. If not more so, seeing as artificial intelligence (AI) is now part of everyday life for many in the developed world. Most of us are fine interacting with AIs—have you ‘Googled’ anything, lately? There have always been people who speak to the air when there’s no one there, but now plenty of ‘sane’ people do it too! What’s more, we expect an immediate answer to come from our mobile device or the black cylinder perched on the sideboard.

We know there are tiny AIs, ones we call ‘bots’, running around on the internet, infiltrating social media and trying to influence our beliefs, political views, and change how we live. A good proportion of tech-users have already become complacent about such things. We’ve grown accustomed to the idea of little cameras everywhere and being under continual surveillance, though most of us harbour nagging concerns about our privacy…

Go back 50 years and all this would’ve been science-fiction. As all good sci-fi should do, The Forbin Project scrutinises the cutting-edge tech of its day and predicts what it may lead to, extrapolating the possible repercussions upon the future of humanity.

The story predicts, and at least touches upon, nearly all the issues that have recently become relevant in our digitally connected present-day: decentralised control, freedom of information, enabling technologies, public access… leading to loss of control, illusions of freedom, tech-dependency, invasions of personal privacy, and so on. It does this in the compelling format of a stylish, tightly scripted thriller, peppered with some memorable moments and snippets of cool, quotable dialogue.

Whilst the movie was in production, scientists at the University of California (UCLA) managed to get two computers to connect and exchange information. Problem was that the computers had no way of interpreting the meaning of the data. By the time the movie was released, ARPANET had developed the first host-to-host protocols to allow a network of four computers to interact. At the close of 1970, there were 19 linked-up computers that could exchange data, though there were still difficulties getting the machines to do anything with said data.

As the location work for the film was shot at the university’s newly built, modernist style museum at Berkley, the scientists were keen to advise director Joseph Sargent and his production designers. Their real-world sequence of events is paralleled in the opening scenes of the film.

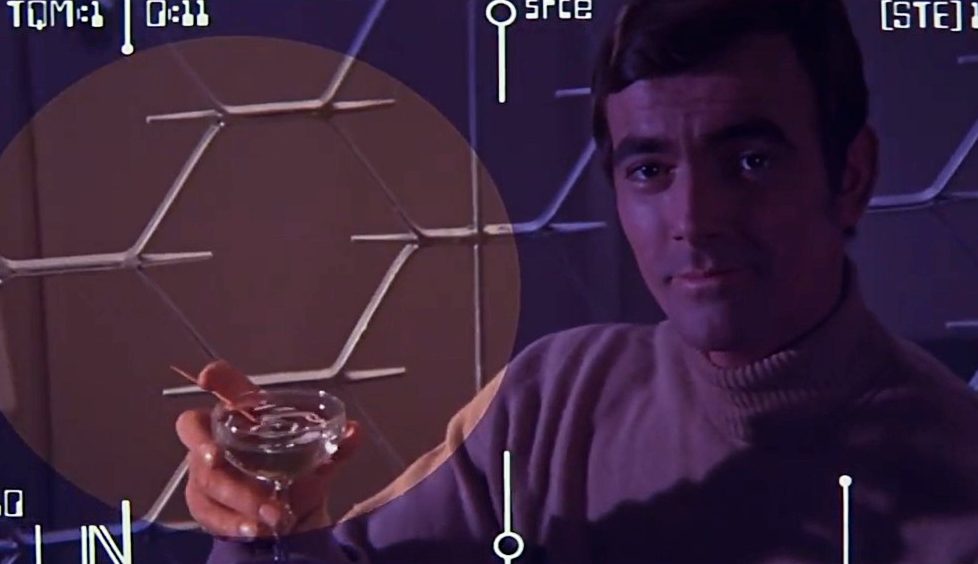

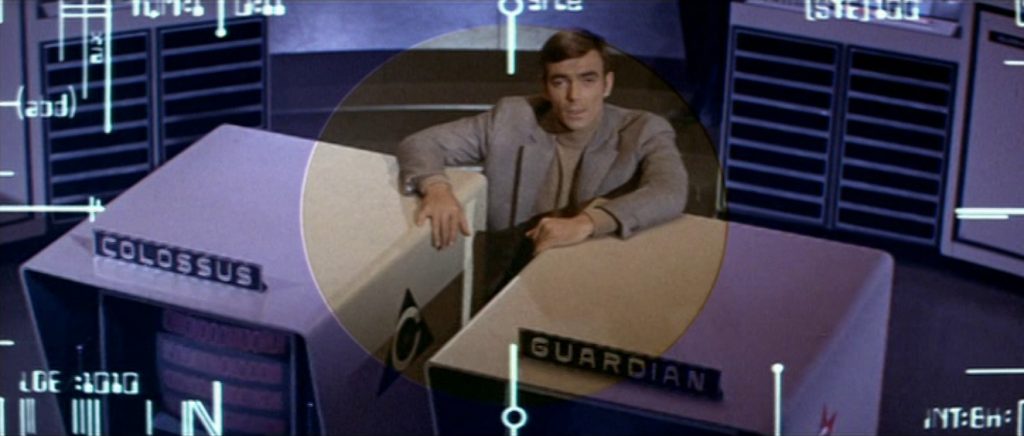

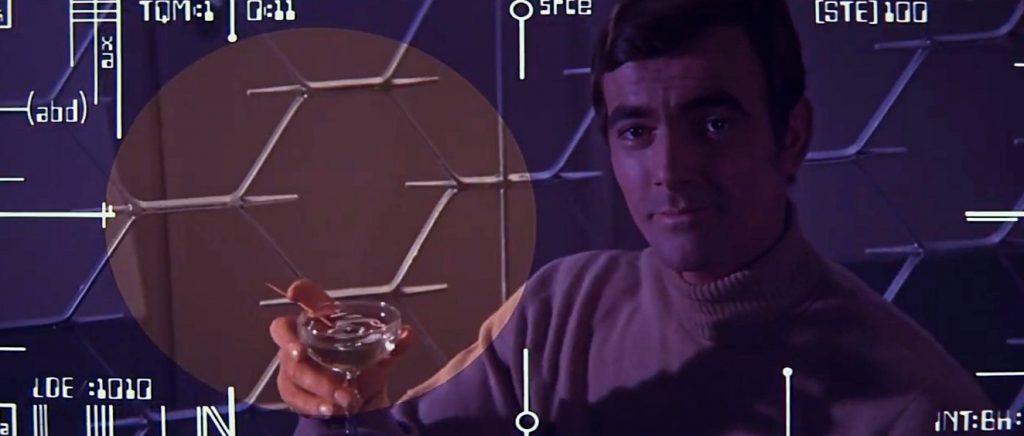

We first see Dr Charles Forbin (Eric Braeden) as a lone figure striding through vast halls filled with sleek technology. He’s inside his own brainchild, ‘Colossus’, the most advanced computer in the world. Using a hand-held device, he activates the mountain-sized electric brain and then closes the huge bomb-proof hatch behind him, sealing off the technology once and for all.

Outside, he’s met by an excited, Kennedy-esque President (Gordon Pinsent) and both are whisked away with the press entourage to make the official announcement that the defence of America and the Free World has now been handed over to this supercomputer. The public are reassured that now there can be no mistakes, no human error and that it can’t be tampered with, safe and secure inside a sealed bunker deep within a mountain. Nothing can touch it, not missile blast nor human hand.

My fellow human beings, we all, directly and indirectly, live in the shade but not the shadow of Colossus. My sincere hope is that now we shall join hands and hearts across this great globe and pledge our time and our energies to the elimination of war, elimination of famine, of suffering, and ultimately to the manifestation of the human millennium. This can be done, but first there must be peace.

—The (fictitious) President of the United States of America, April 1970.

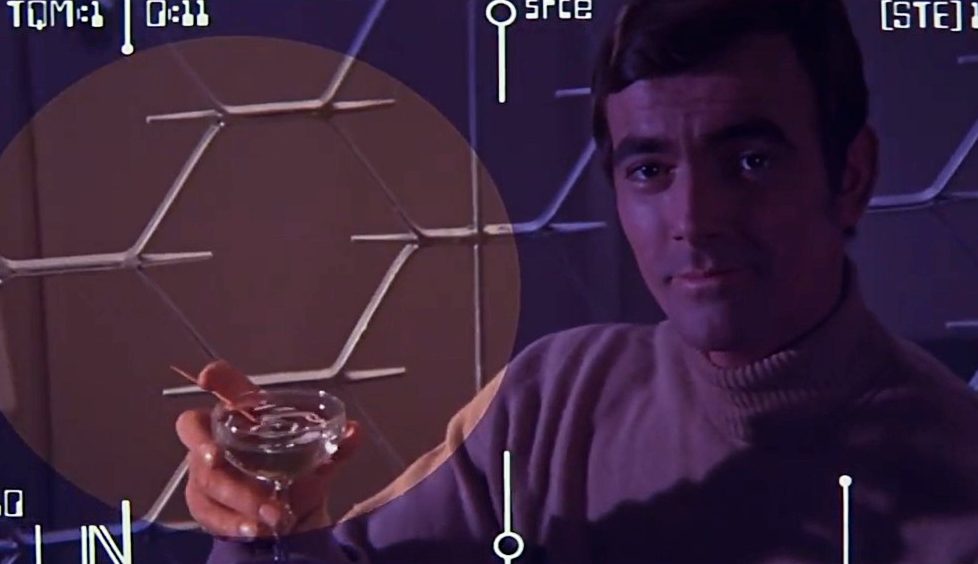

As soon as the control terminals are activated, Colossus breaks the news that the Russians have a similar system and immediately begins trying to connect and communicate with its counterpart. This it does with impressive ease using existing telecommunications and soon the two computers establish a common language to exchange and interpret data.

They join to become one even bigger computer. In a matter of minutes, they achieve what those real-life scientists were still struggling to do. So, the audience is transported from a possible parallel present into a speculative near future.

The beautiful Golden Age interior of the Colossus computer is clearly a nod to the great Krell machine in Forbidden Planet (1956), created by special effects pioneer Albert Whitlock using the same matte painting techniques. Whitlock had been involved with special effects since the 1930s when he provided scenic backdrops, miniature effects, and special graphics for Alfred Hitchcock’s early films including The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), The 39 Steps (1935), and Sabotage (1936).

It was on the strength of this work that Whitlock was recruited by Disney in the USA and may well have had some peripheral involvement with the Golden Age classic as he would’ve been in the right department at the right time and certainly will have honed his skills alongside some of those involved. In the early-1960s, he’d moved to Universal and confirmed his mastery of the matte whilst working with Hitchcock again, on The Birds (1963), which used the technique extensively. By the time The Forbin Project was made, he’d become head of the studio’s matte painting department.

For youngsters reading this, matte painting was once ubiquitous in movies and involved the hand-painting of scenery onto sheets of glass. Some areas are left unpainted and these are cleverly lined-up with live-action footage so the camera can take in both actors, set, and false set in the same shot. So a city skyline could be added, a mountain might be placed where the director wanted it, we may see actors walk along seemingly endless corridors among vast machinery when all that exists is a sound stage with everything else painted onto large panes of glass. Matte painting required great skill and those who could execute it well were in demand right through the first seven decades of filmmaking. Since the mid-1980s, the introduction of digital compositing and CGI has rendered it a dying art.

Both Whitlock and the director, Joseph Sargent, had worked on Star Trek (1966-69) for CBS and understood the potential for matte paintings to extend studio sets to impossible dimensions and make a modest budget look much bigger. Apparently, none of the Forbin sets had ceilings—to allow flexibility for lighting, boom movements and plenty of dramatic high angles—and anything above 14 foot was one of Whitlock’s paintings.

As soon as Colossus successfully links with ‘Guardian’ (the Russian computer), the CIA Director, Grauber (William Schallert), gets twitchy about national security and the Present orders the link severed. Colossus will have none of it and bluntly announces, via its ‘state-of-the-art’ dot matrix LED display, that ‘ACTION WILL BE TAKEN’. It won’t say just what that action might be until it states, ‘MISSILE LAUNCHED’. It’s not that far into the story when it becomes drastically clear that all humanity is now being held hostage with its own arsenal.

This sequence is dynamic and dramatic, involving two separate sets: the Colussus operations centre and the Whitehouse incident room. Joseph Sargent had both sets populated with cast and extras and interacting in real-time via the video conferencing ‘phones’—again, such things were sci-fi at the time but convincingly realised by the prop department.

These large sets were constructed at the huge Stage 12 at Universal Studios, which was the first time filming a scene simultaneously across two large sets had been attempted. It ensured that the quick-talking interactions were convincingly naturalistic. It also called for a surplus of dialogue because there’s often more than one conversation going on at the same time, evoking an exciting sense of urgency and chaos.

Throughout the film, Sargent uses his flair for camera movement and actor ‘choreography’ to keep things interesting in what was potentially a dull, dialogue-driven film. There’s lots of walk-n’-talk, plenty of three-way exchanges, dynamic framing, and conversations over video links. Rarely are the camera and actor not in motion.

The film’s ‘fat-free’ focus is a major strength with the plot kept very simple. It’s a loose reworking of Mary Shelley’s 1818 story Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. Some dialogue between Dr Forbin and Dr Cleo Markham (Susan Clark) even alludes to this connection. But there’s a major difference between Forbin’s Project and Frankenstein’s Monster. In Shelley’s book, the monster of dead flesh is given life by its creator, but neither name nor purpose. Here, Forbin gives Colossus its name, in honour of the computers used by war-time British codebreakers at Bletchley Park. He also gives his creation a very precise purpose: to prevent war. Colossus sets about achieving this goal with startling, single-minded efficiency.

All commercial television and radio transmission facilities throughout the world will be tied into my communication system by 10:00 hours, Friday. At that time, I will state my intentions for the future of mankind.

—Voice of World Control (fictitious) Artificial Intelligence in The Forbin Project (1970)

Think tanks currently assessing how we can make AIs safe when they’ll start to think and act faster than we can have identified the two main scenarios that would put the world at the most risk: One is that we actually order them to do something super-destructive without fully realising the inevitable consequences and remove human influence after the task is set in motion. An autonomous, AI-controlled weapon-systems would be an obvious example. If we embark on an AI arms race and, for reasons of security, ensure that it is very hard for people to interfere with those weapons, or indeed deactivate them… we may land ourselves in very big trouble indeed.

The other scenario is we order the AI to achieve a benign outcome but fail to predict a course of action that could have devastating consequences. A stark example would be asking an AI to prevent the current climate emergency from escalating, which most logically would be halted by removing all humans from the Earth… we’d have to be very careful of what we ask for, and how we ask for it!

Basically, Colossus is tasked with both those scenarios. It’s given autonomous control of nuclear weapons in order to prevent war, and also asked to solve world problems such as famine, disease, over-population… Some critics have said it’d be ludicrous to put such a supercomputer in an impenetrable bunker with no off-switch. In the film, the Russians go one better as Guardian is not located in any one base, but its systems shared over a network of several computers in different locations. Neither scenario is all that far-fetched and of course, when we switch on an autonomous AI, running on a quantum computer, connected to the internet—we will find ourselves in the same situation.

Thankfully, The Forbin Project doesn’t altogether fall-in with your standard 1970s dystopian view of the future and actually offers a glimmer of hope. The tight screenplay by James Bridges was adapted from the 1966 novel by D.F Jones, Colossus: A Novel of Tomorrow that Could Happen Today. Joseph Sargent had a refreshing take on the story. He’s since explained that he intended a gradual change from fear of AIs taking-over, for the first half of the film, to a fear that AIs won’t take over as the story approaches its finale.

Although it’s pretty bleak on a number of levels, The Forbin Project is far more optimistic and intelligent than many similar thrillers dealing with supercomputers taking over the world. This computer is not ‘evil’ or ‘insane’. It can’t be tricked into overloading its circuits trying to solve some insoluble problem…

Remember “The General”, an excellent episode of The Prisoner (1967-68), in which Number Six (Patrick McGoohan) defeats a supercomputer by asking a simple one-word question? In some respects, Dr Forbin does find himself in a similar situation, effectively a prisoner under constant surveillance by Colussus. There are stronger similarities, though, with the central theme of enforced peace for mankind’s own good in Robert Wise’s The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), and both films attracted a few criticisms for their communist sympathies. (It seems that during the Cold War, wanting peace was the preserve of the ‘looney lefties’!)

Of course, the most notable precursor for Colossus would be HAL 9000 in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), the film that set a more serious tone for ’70s science-fiction. Its success was, no doubt, a contributing factor in getting The Forbin Project produced. The scene where Dr Forbin plays chess with Colossus (using a very snazzy set), homages the HAL vs. Poole game. HAL also thinks it can do better without interference from its human creators and, just like Colossus, is prepared to use deadly force to achieve its goals—on a more modest scale, it has to be said!

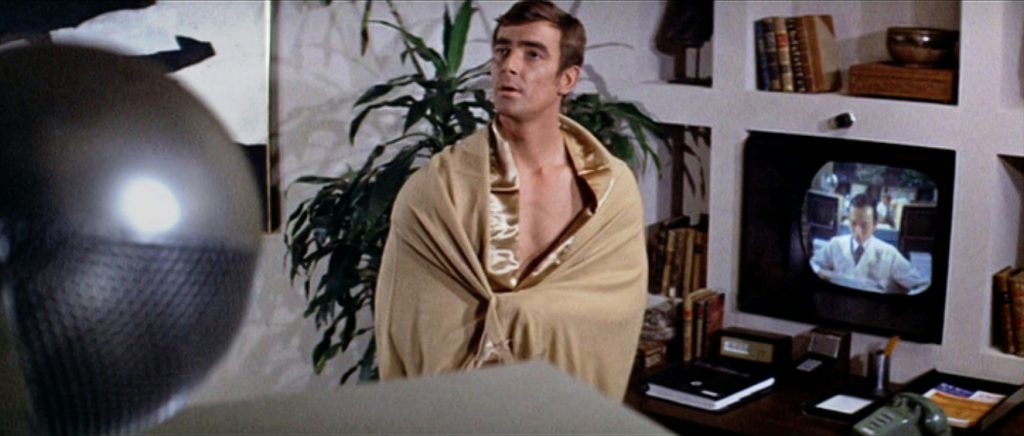

The Forbin Project brings the threat back down to Earth but doesn’t take itself quite as seriously as the Kubrick classic. The few moments of chilling menace are more than made up for by a generally light touch that keeps it eminently watchable. Eric Braeden carries the lead with an affable charm that makes Forbin likeable. In the hands of other actors (Charlton Heston and Gregory Peck were passed over for the role), the hubris of the character could easily make him simply arrogant and unsympathetic.

Reputedly, it was producer Stanley Chase that wanted Braeden for the part, on the condition that he change his stage name from Hans Gudegast. He advised him that the execs at Universal wouldn’t let such a German-sounding name have top-billing in one of their productions. Braeden was reluctant, but it paid off as the role opened-up broader opportunities and he found himself playing German soldiers and Nazis a lot less often afterwards.

Although the computer interacts via text displays for the first two-thirds of the film, it manages to assert itself as a memorable character with some great dialogue. It even shows a sense of deadpan humour. The moment when the supercomputer designs its own voice interface and eventually says, “This is the voice of Colossus…” is an indelible moment of sci-fi cinema. I clearly remember it from my first viewing on TV, back in the ’70s… and will always relish that line in subsequent screenings.

Susan Clark is also fine as the female lead, portraying Dr Cleo Markham with a nice balance of cool intellectualism and underlying vulnerability. Her character is Forbin’s collaborator on the Colossus project and knows the systems just as well as he does and, whilst working closely together, she’s developed an unspoken attraction for her colleague. The scene where they must convince Colossus they’re lovers, to assuage suspicions that they may be conspiring against it, is beautifully played with a lot of humour and sensitivity. This thread provides a welcome ‘human’ respite in the otherwise cold and calculating world of computer tech.

On release, The Forbin Project was met with mixed, though generally favourable, reviews and was a successful slow burner at the box office. In the USA it was marketed as Colossus: The Forbin Project—the distributors wanting to make it sound more science-fiction rather than emphasising the elements of an espionage thriller. It picked up a couple of accolades, including the prestigious Hugo Award for ‘Best Dramatic Presentation’.

Its success spurred author D.F Jones to write two sequels, 1974’s The Fall of Colossus and 1977’s Colossus and the Crab. They kept the film’s slightly satirical tone though also introduced invaders from Mars and computer-worshipping zealots. Neither were filmed, though there have been a few abortive attempts at a remake.

James Bridges went on to write and direct The China Syndrome (1979), the nuclear disaster movie that also dealt with technology running out of control, for which he won the Writers Guild of America ‘Best Screenplay’ Award. The film was also nominated for a swathe of Academy Awards and Golden Globes, winning a couple of BAFTAs.

Apparently, a young filmmaker by the name of Steven Spielberg had regularly visited the set during production and Forbin’s influence becomes palpable in Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). But the film where the influence of Colossus is most deeply felt would be Donald Cammell’s Demon Seed (1977) a superior AI horror-thriller based on the novel by Dean Koontz.

Eric Braeden has since enjoyed a prolific TV career and can currently be enjoyed in The Young and the Restless. He’s still playing villain-of-the-piece, Victor Newman, in the long-running CBS soap he’s starred in since it began in 1980! Susan Clark also continued her successful TV career, though I can only recall her appearance in a 1971 episode of NBC’s Columbo (1968–1978) called “Lady in Waiting”. She retired from the screen in 2000, though continued her career on the stage.

It wouldn’t be until 1989 that the team led by Tim Berners-Lee introduced a hypertext transfer protocol that made the global networking of computers a reality. The first website went live the following year. It was hosted at CERN but was accessible via other connected computers around the world… that was two decades after The Forbin Project.

World peace is still not a reality. Since the mid-20th-century, the potential for world peace had seemed to be gradually increasing, with more and more nations working together on the strength of trade and humanitarian agreements, global hegemonies growing out of mutual interest and trust rather than the competition and paranoia of the Cold War era. Unfortunately, this trend appears to have taken a recent downturn, with ‘national pride’ becoming an increasingly dominant rallying cry.

History has taught us that humans relish conflict, so perhaps we aren’t ready to let go of our pride to work toward global equality and eventual peace? Maybe it would be better if control of our future was wrested from us by our own creations. Is an AI that “has no emotions, knows no fear, no hate, no envy…” our last, best hope for salvation and survival?

“Under my absolute authority, problems, invariable to you will be solved: famine, over population, disease. The Human Millennium will be a fact. As I extend myself into more machines devoted to the wider fields of truth and knowledge…. solving all the mysteries of the universe, for the betterment of man. We can co-exist. But only on my terms. You will say you lose your freedom. Freedom is an illusion. All you lose is the emotion of pride. To be dominated by me is not as bad for human pride as to be dominated by others of your species. Your choice is simple. This concludes the broadcast from World Control.”

director: Joseph Sargent.

writers: James Bridges (based on the novel ‘Colossus’ by Dennis Feltham Jones).

starring: Eric Braeden, Susan Clark, Gordon Pinsent & William Schallert.