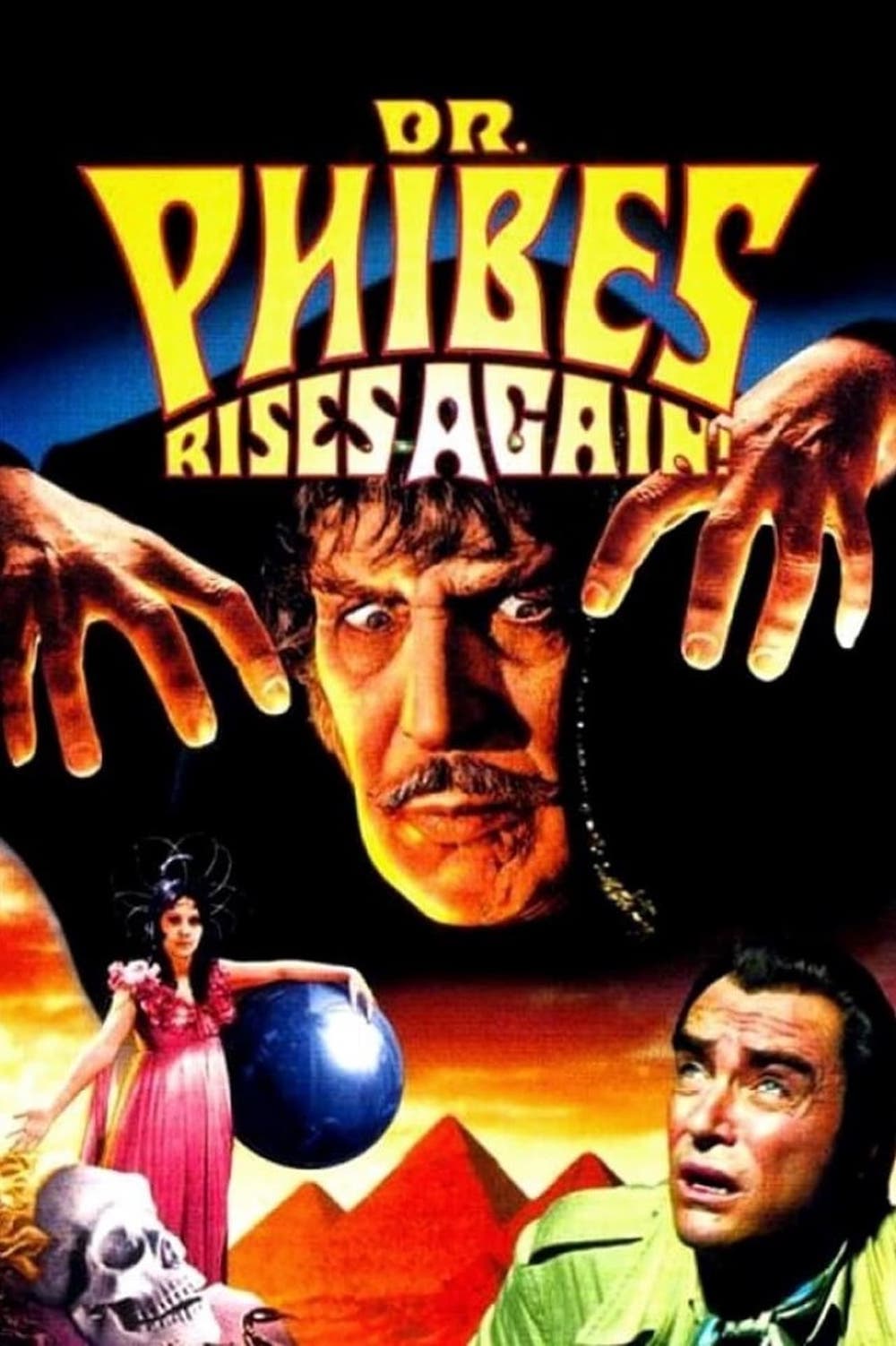

DR. PHIBES RISES AGAIN (1972)

The vengeful doctor rises again, seeking the Scrolls of Life in an attempt to resurrect his deceased wife.

The vengeful doctor rises again, seeking the Scrolls of Life in an attempt to resurrect his deceased wife.

Those who loved Abominable Dr. Phibes (1971) will undoubtedly love this follow-up… just not quite as much. It’s great it was made, though sad it wasn’t the film writer-director Robert Fuest hoped it would be, never matching the audacity or artistry of its predecessor. It’s far more satisfying if approached as an epilogue rather than a sequel, as it offers some solutions to the puzzling aspects of the first—whilst introducing a few more of its own. It builds to a suitably camp, yet poetically satisfying finale too. But, along the way, it’s really more of the same but with less sophistication. However, Dr. Phibes Rises Again is well worth the time as there are some surprises and moments of beauty.

Producer Samual Z. Arkov, at American International Pictures (AIP), kept his trans-Atlantic distance during the production of The Abominable Dr Phibes but now had ambitions of building upon its unexpected box-office success. So, rather than trusting the creatives responsible for that initial triumph, he decided to intervene and ensure the sequel ‘benefitted’ from his own expertise as a seasoned producer.

After all, he’d been behind some genre classics and many of Vincent Price’s most memorable movies—including Roger Corman’s adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe stories, The Pit and the Pendulum (1961), Tales of Terror (1962), The Raven (1963), and The Tomb of Ligeia (1964). However, Price’s contract with AIP had expired and Arkov had to tempt him back to reprise Phibes with a handsome fee of around $75,000, making it one of his final starring roles. The following year he headed the cast of Theatre of Blood (1973), a similar horror-comedy in its sentiment, before his career was swamped by a run of television movies and cartoon voiceovers.

To ‘improve’ the formula, Arkov stipulated there would be at least one guest star and a murder in each reel, so ordered a rewrite to ensure that happened. This results in some of the death scenes losing their narrative function in favour of side-show sensationalism. He then intervened at the editing stage, ordering some scenes to be swapped around, curtailed, or excised entirely so as not to slow the pace. Around 10-minutes were trimmed, resulting in an uneven narrative and diminished dramatic punch.

Any good comedian will tell you timing is crucial, and horror follows similar rules to comedy. Both genres rely on a degree of violation and succeed by confounding expectations with a punchline, eliciting mirth and laughter… or shock, dread, or a scream. This is doubly so in the case of Phibes, which are basically comedy horrors.

Anton Phibes (Vincent Price) does very bad things with justification. At least that’s how he sees it. He’s pursuing the secret of eternal life not for himself, but for the love of his life. And what an all-consuming love! It survived the deaths of both the lovers and the end of the first film left us in little doubt that Phibes has indeed risen from the dead, physically and not just figuratively speaking—a living body doesn’t recover from embalming!

A compiled montage recaps the events of Abominable with a narration from prolific voice actor Gary Owens, known mainly for children’s cartoon characters. Tacked on by distributors AIP, it sets a suitably silly and overblown tone, reminding us that Dr Phibes was a world-famous organist who played “flamboyant songs of triumph and revenge” and had entombed himself along with his deceased wife, Victoria (Caroline Munro) until a rare alignment of the moon that occurs every 2,000 years triggers their resurrection. We’re also told of a “mountain overlooking the Valley of the Pharaohs where years ago he prepared a shrine.” Great stuff, but we’ll be told all this again, and again, later in the first act.

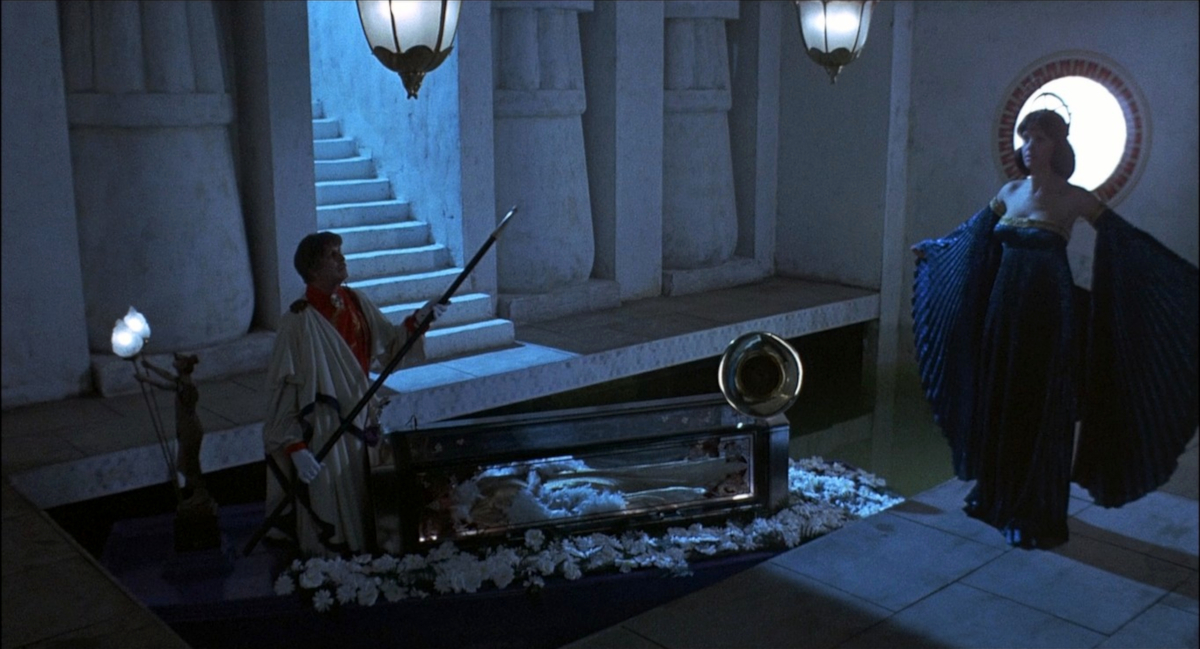

Immediately we have an answer to one of the questions raised by the first film: who or what is Vulnavia? The mysterious and beautiful companion of Phibes was dissolved by acid and definitely died but now answers her master’s summons, gliding from some nether void along a geometric corridor of mirrors in the form of Valli Kemp, replacing Virginia North. So, she’s clearly a supernatural being, a sprite of some sort not unlike Prospero’s Ariel but with an exquisite Art Deco fashion sense.

As they rise from the basement crypt via an organ-powered elevator, Phibes seems surprised to find his mansion reduced to rubble, even though his final command to the previous Vulnavia had been to destroy all he’d built. What upsets him most is the safe lying broken open, its vital contents pilfered, which we learn was an ancient Egyptian papyrus bearing the plans of a lost temple. Why he didn’t keep such an essential document close at hand in his impenetrable basement, and how he instantly knows who has stolen it is never fully explained, hinting perhaps at a broader, unexpounded backstory.

Phibes surmises the vital map is now in the hands of Darrus Biederbeck (Robert Quarry, fresh from starring in two Count Yorga films for AIP) and sets about stealing it back. This leads us nicely into the movie’s first murderous and most distinctively Phibesian set pieces. Let’s be honest, the main attraction is the series of inventive, elaborately staged murder scenes played out with deliciously camp malevolence. In this way, Dr. Phibes Rises Again follows the same format, which finally proves detrimental to both plot and pacing.

We wonder what could be in the raffia basket that Vulnavia sneaks into the Biederbeck residence where his burly butler (Milton Reid) passes the evening playing snooker with himself. The hapless crony is first distracted by a strange rattling and whirring that he traces to a couple of giant pythons. He dispatches these with ease by whacking them with his cue only to discover on closer inspection their ingenious clockwork mechanisms. So, when he sees another on the snooker table he’s not too worried and decides to examine it more closely. Big mistake.

The audience is in on the gag as we’re afforded a close-up that clearly shows the cogs and key assembly is attached with sticky tape. This time to a live snake. Which is clearly a calm and non-venomous python. I suppose, in those days, snakes were snakes and the bigger they were the scarier but those familiar with the earlier film know we’re not to take things so seriously. The whole affair is another celebration of theatrical artifice, so when the python bites the butler and he panics, cutting the wound to suck out the ‘poison’ we go with it, not realising we’ve just been wrong-footed and set up for the real deathblow.

He rushes to the phone, presumably to call for a doctor and, when he raises the phone to his ear, a spring-loaded spike in the form of a golden serpent pierces his skull. In one ear and out t’other, as they say. It’s a smoothly done stop-motion effect and a great opening gambit that would’ve sat proudly alongside the theatrical deaths of the first film. It’s also a homage as this same method of remote murder was used 33 years earlier by another deranged doctor seeking retribution—the great Boris Karloff in the role of The Man They Could Not Hang (1939).

Phibes and Vulnavia will successfully retrieve the papyrus and make preparations for their journey to Egypt, as Phibes is fond of mansplaining, “where mystic lines converge, we’ll find the door that separates the living from the dead!” He intends to harness the powers of the eternal river of life to revitalise himself and his dormant wife.

Robert Quarry plays Biederbeck as a suitably cold and calculating nemesis for Phibes. Both men share similar obsessions, and both are as steadfastly focused on their singular goal. Biederbeck is much more concerned about the whereabouts of his stolen papyrus than the death of his servant or apprehending the murderer. This inhuman coldness drives a substantial wedge between him and his much younger fiancée Diana (Fiona Lewis). She doesn’t quite understand why everything seems to depend on finding an obscure temple.

The ensuing Egyptian theme retrospectively explains why the deaths in the first Phibes film were inspired by the Biblical plagues. This time around, though, the methods of murder are not as artistically sound and don’t follow any obvious thematic pattern. In terms of their set-up and reveal, they also lack that element of mischievous tease. For the most part, we’re denied that insight into their meticulous preparation and so miss out on the fun of predicting how each will unfold. Here they seem relatively unplanned and over too quickly with the first, snake-based one being the most interesting and inventive in its, forgive the pun, execution.

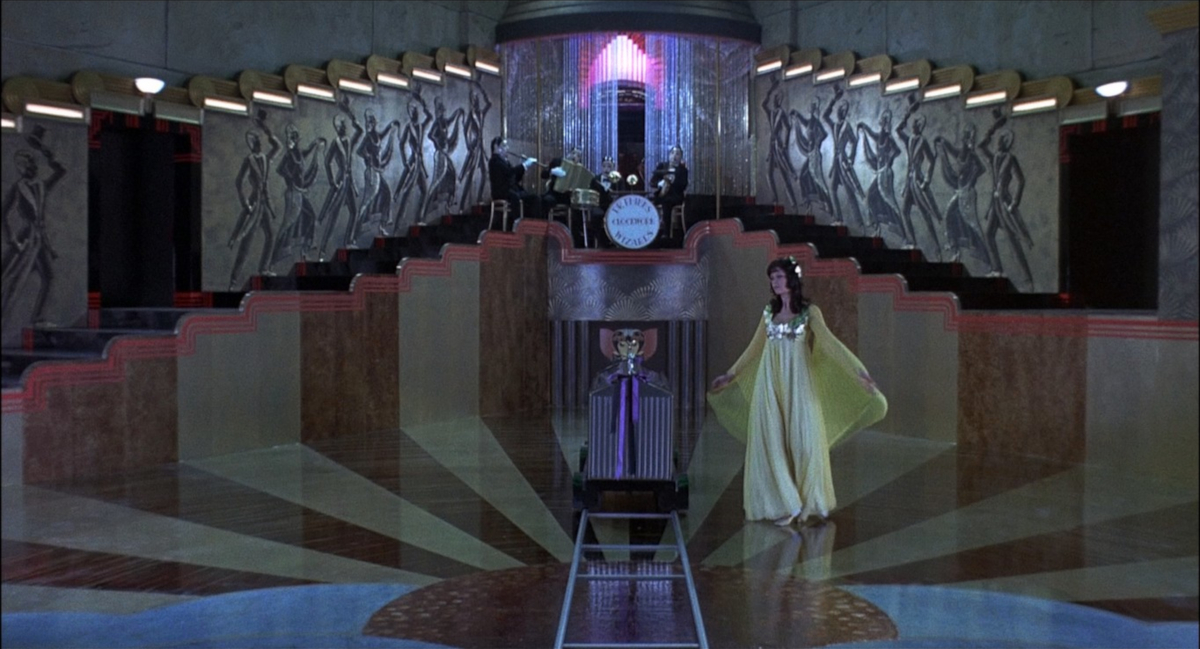

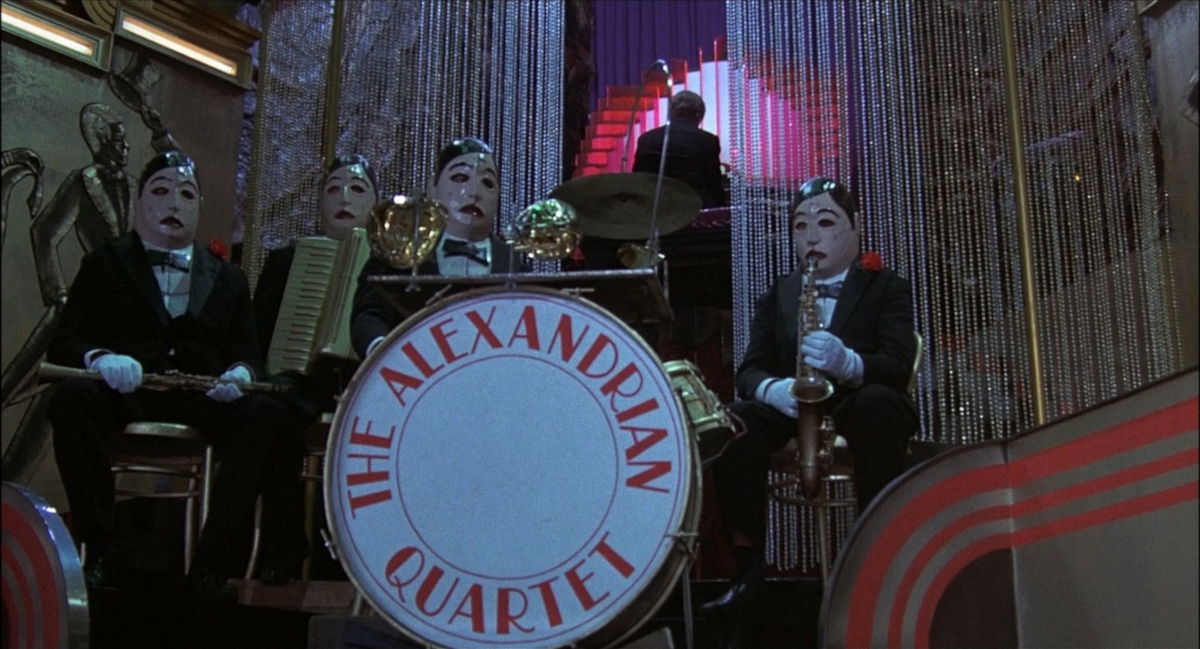

The next death is more implied than explicit and sees the return of Hugh Griffith (who played the knowledgeable Rabbi in Abominable) as Harry Ambrose, an archaeologist associate of Biederbeck who stumbles upon the Phibes cargo stashed in the ship’s hold en voyage to Egypt. Among the strange props, including the creepy clockwork quartet, is Victoria Phibes. She’s preserved and presented as some sort of automaton of a seductive nightclub singer in a ‘penny arcade’ glass cabinet. Inexplicably, there’s also a huge promotional gin bottle…

We don’t get to see exactly what transpires, one can only assume it was rather ungainly, but Ambrose somehow ends up inside the big bottle and Phibes nonchalantly hoists it overboard. Again, Biederbeck doesn’t seem concerned about the loss of his erstwhile confidant and badgers the ship’s captain (Peter Cushing) to curtail the search and keep the cruise on schedule.

When bottle and body wash ashore, Detective Trout (Peter Jeffrey), fresh from investigating the mysterious murder of a man found with a golden snake through his skull, is called to the scene. Two baffling deaths in such swift succession remind him very much of the Phibes case from three years prior. When he and his irascible superior, Superintendent Waverley (John Cater) question the owner of the shipping line, Mr Lombardo (Terry-Thomas) and hear that a passenger had a set of clockwork musicians and an organ loaded as cargo, they have no doubt Phibes is once again at large. It’s always great to see Terry-Thomas but a surprise as his character died in the first film but here, he’s playing an entirely different one. Well, Terry-Thomas generally plays variations of Terry-Thomas and doesn’t disappoint in this all too brief cameo which reads as a classic dryly comic sketch.

This is followed by another witty detour involving Trout and Waverley questioning Miss Ambrose (Beryl Reid), a relation of the man in a bottle who knew the reasons for his trip to Egypt and the location of the archaeological site he was heading for. Beryl Reid was another stalwart of British comedy but had also displayed her serious acting chops in the Robert Aldrich drama The Killing of Sister George (1968), controversial for its groundbreaking lesbian scenes. She’d recently earned some horror kudos for The Beast in the Cellar (1971) but this time she’s on safer ground playing the kind of dotty English spinster she was best known for.

It’s also great to see the two policemen reprising their roles and later they’ll treat us to some gentle double entendre whilst sharing a camp bed—all very British, y’know. Again, that English eccentricity is carried over from the first film. It really captures an aspect of the era as the carefree swinging sixties transition into the more troubled seventies, echoing the film’s period setting of the latter years of the Roaring Twenties as the economic depression of the 1930s loomed in the ever-deepening shadow of impending war. Now, 50 years on, it’s doubly nostalgic.

No other actor could don the robes of Phibes like Vincent Price and he does another brilliant job of physical acting, adding irony and a pervasive sense of fun to temper the horror. It shouldn’t work. In the hands of any other actor, it probably wouldn’t have. Apparently, for each scene, his lines were read aloud on set so he could emote at the right pace, overdubbing his own dialogue later. This time around his character doesn’t come across quite as intense and single-minded and there are gentler moments when Price’s improvisations lighten the mood. Having said that, his motivations are not as clear and some of the murders come across as simply sadistic, seemingly no longer fuelled by that intense passion.

His chosen methods of killing now seem vindictive rather than vengeful and this changes the tone somewhat. It would be interesting to see a director’s cut as I suspect some of the murder scenes were reordered after the print was taken out of Fuest’s control. The death of Biederbeck’s archaeological assistant, Stewart (Keith Buckley) appears to have been brought forward in the narrative. It’s by far the most inventive and baroque of the set pieces involving a giant golden scorpion sculpture and a key sealed inside a ceramic model of the iconic dog mascot for His Master’s Voice (HMV) records.

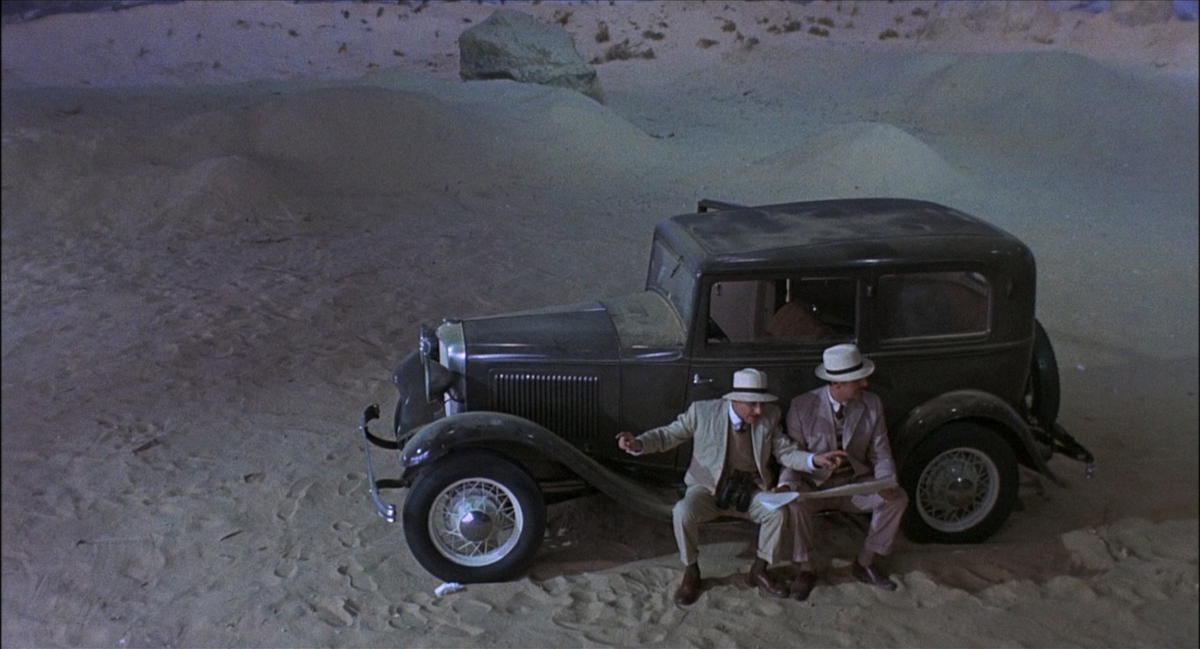

Stewart’s murder is the second to occur after the parties have arrived in the deserts of Egypt, converging to unlock the secrets of the ancient temple buried beneath a mountain. Necessity triggered an earlier killing when another of Biederbeck’s team, the gruff and manly Shavers (John Thaw), discovers the tunnel leading to the Art Deco lair of Phibes and Vulnavia, and so a trained guard-eagle is dispatched to, well, dispatch him. Then we get the scene where Vulnavia silently, seductively lures Stewart away from the base camp to his drawn-out and dramatic demise.

Only after this memorable murder, does Bieberbeck manage to find the secret chamber where Victoria Phibes is concealed within a magical sarcophagus and has it removed for study. Anton Phibes then vows to kill ‘every last one of them’ in order to retrieve his beloved and consign his secrets to the dust of the desert. So why he’d already killed Stewart remains unclear, unless that death was recut and brought forward by order of Sam Arkov to keep to his ‘one death per reel’ rule. (Further cuts were made to the US release, removing any gruesome details to secure its PG rating.)

After a few more marvellous murders, Phibes repeats the pattern of poetic justice from the first film. He kidnaps Biederbeck’s paramour, Diana, sedates her and straps her to what appears to be a golden bunk beneath a ceiling of slowly descending bejewelled serpents, each with a sharp fork for a tongue. Throughout, Biederbeck’s maintained that his own callous behaviour was driven by love for her and the desire to live out their lives together. Knowing that his life is nearing an end, he desperately desires the secret of eternal life so they can marry but claims her life is more important than his own. They’re motivations that echo those of Phibes who doubts his sincerity so rigs up a deadly trial so that Biederbeck can save only himself or Diana. The final scenes between Quarry and Price are strong and one wishes they’d had more screen time to play off each other.

The original Dr Phibes was out of nowhere, unpredictable and totally fresh. Rather than attempt to replicate this originality and take things in a new, equally unpredictable direction, the sequel is trying a bit too hard to recapture what made the first film great. But one gets the feeling those involved weren’t quite sure what that was. Of course, one of the main problems is that the producers at AIP wanted to get hands-on and, after a certain point, they told director Robert Fuest to get his hands off.

At times the film manages to match the visual sumptuousness of the first with some gorgeous sets, again designed by Brian Eatwell. They’re a delightfully anachronistic fusion of Art Deco and Pop Art that perhaps prefigure the visual stylings of Dario Argento’s Suspiria (1977), another film built around a series of elaborate death scenes. But Phibes appears to have risen into more restrained surroundings with interiors small enough to warrant generous use of wide-angle lenses by cinematographer Alex Thomson. Under the direction of Fuest, he achieves a welcome, expressionistic dreaminess. However, although they were working with a slightly higher budget, the sequel somehow looks cheaper and, apparently, much of the script was trimmed due to budgetary constraints.

Dr Phibes Rises Again may not manage to recapture the magic of its predecessor but leaves us with perhaps the finest and most memorable image of both films as Anton and Victoria punt off down a tributary of the Nile to a reprise of Harold Arlen’s song, Over the Rainbow. Depending on which version you find, the scene may be accompanied by the priceless Vincent Price vocal rendition! Possibly because of rights issues, it was replaced in many releases but restored in the Blu-ray versions I’ve seen.

Although it leaves things as open as the first film, it provides closure for Anton and Victoria and allows the viewer’s sensibilities to draw their own conclusion—are the star-crossed couple to be eternally doomed in darkness, reunited in the hereafter, or resurrected to live happily ever after… It leaves a nice, poignant ambiguity, rendering any of the planned sequels redundant.

UK | 1972 | 89 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Robert Fuest.

writers: Robert Fuest & Robert Blees.

starring: Vincent Price, Robert Quarry, Valli Kemp, Peter Jeffrey, Hugh Griffith, Fiona Lewis, John Thaw.