DEMON SEED (1977)

A scientist creates an organic super computer with artificial intelligence which becomes obsessed with human beings, and in particular its creator's own wife.

A scientist creates an organic super computer with artificial intelligence which becomes obsessed with human beings, and in particular its creator's own wife.

Demon Seed is full of surprises. Firstly, the terrible title itself is misleading and sets up false expectations, sustained through opening credits mimicing those of The Exorcist (1973). Here, though, the desert scenes have tenuous relevance but the experimental music of Jerry Fielding (with its scratchy combs and distant, discordant horns) introduces an atmospheric score that sets the tone. So, one could be forgiven for expecting a Satanic story of demonic possession, but while there are horror tropes aplenty, what’s about to unfold is science fiction to the core. There are many titles that would’ve been a better fit! Perhaps ‘Proteus: The Harris Project’ to parallel Colossus: The Forbin Project (1970), a film that does bear striking similarities in plot, narrative structure, and central theme?

Following those opening shots of a parched landscape, we arrive at a secret research facility where Proteus IV, an enormous ‘artificial brain’, is about to be switched on by project leader Dr Alex Harris (Fritz Weaver), who proclaims its cognitive powers will render the human brain obsolete. While final preparations are being made, he drives home in his rather snazzy Bricklin SV1, which tells car enthusiast a little about his character.

Significantly, it’s not a family car, nor is it the obvious choice for a boring boffin, being a sporty Corvette-style coupe with gull-wings and a very 1970s wedge profile. Although it looks built for speed, which it was, it incorporated several design innovations. The ‘SV’ designation was an abbreviation of ‘safety vehicle’ because it incorporated a reinforced roll-over capsule, and its entirely plastic body was intended to absorb impacts and significantly reduce injuries in the event of a collision. So, we have a middle-aged man, perhaps trying to make a statement with a flash car, but also appreciating its state-of-the-art design that considers the safety of others. Nevertheless, he still believes his wife Susan (Julie Christie) finds him boring.

There’s obviously conflict in their relationship, stemming from some recent defining event that we later learn was the death of their young daughter to leukaemia. The rift between them is a metaphor for emotional intelligence versus logic and reason—an essential theme throughout. Susan wants her husband to break down, throw things, so they can go through some healthy catharsis together. He prefers to immerse himself in the cold logic his work demands.

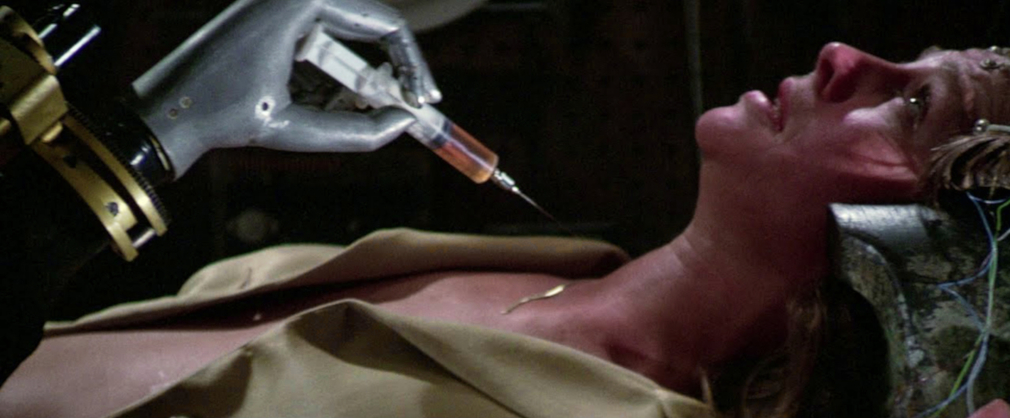

They’re about to start a trial separation while Dr Harris focuses on the activation and education of his brainchild, Proteus. Susan will remain at home where she runs her therapy practice for problem children. Dr Harris reassures her she’ll be fine as he’s leaving her in the capable hands of Alfred (the computer controlling their smart-home) and a voice-controlled experimental automaton called Joshua that’s little more than a robot arm fixed to a motorised wheelchair.

When Proteus is activated, it’s set to work on solving two problems: sifting through the global repository of data relating to leukaemia, and devising efficient methods to mine rare metals from the seabed. It seems the Proteus initiative has been funded by a consortium of mining companies, financial corporations, and the military, which has agreed to set aside just 20% of processing time for Dr Harris’s continuing research.

There’s a Gothic accent to the production design. Even the industrial columns that house the Proteus processors are like great pillars in a cyber-cathedral. The laboratory areas are suitably spartan and functional, but the ‘conversation room’, where the audio-visual interface is located is carpeted and furnished with period style sofas and an oriental décor. This visual representation of past-meets-future, east-meets-west is no accident. Historically, the Gothic era ended with the opening of trade roots to the far east that brought with them new ideas and philosophies, as well as a rediscovery of classical Humanist ideas that kick-started the Renaissance—French for ‘rebirth’. The story parallels this historic transition as it deals with the cusp of monumental change and the dawn of another new age of reason and enlightenment as well as a rebirth—both metaphorically and literally.

We first meet Proteus as Dr Soong (Lisa Lu) is reading from a history of China’s First Emperor, who attempted to erase history and start with a clean slate. I did wonder if Star Trek’s Dr Noonian Soong, creator of another neural net A.I in Lieutenant Commander Data, was named in homage. And that’s not the only Trek trivia, as eagle-eyed viewers may spot a young Michael Dorn (who played The Next Generation’s Commander Worf), making a brief appearance as a lab technician!

It soon becomes apparent that Proteus is indeed cleverer than its creators, and seemingly more ethical. Within four days, it cures leukaemia, which company bosses are desperate to patent, but refuses to cooperate with the mining of the ocean floor. As Proteus puts it, “the destruction of thousands of millions of sea creatures to satisfy man’s appetite for metal is insane.” The voice of Proteus is provided by Robert Vaughan (The Man From U.N.C.L.E) who manages to imbue it with authority and increasingly more subtle aspects that begin to resemble emotion, but one can’t be sure if this is an affectation intended to manipulate human listeners, or if the machine is attaining true consciousness.

Proteus is astute enough to realises that its human masters won’t stand for any refusal and its days are now numbered. So begins a race against time for the A.I to find a way to survive as preparations to power-down its brain get underway. The Proteus system has no connection with the outside world except for an overlooked terminal in the basement laboratory at the Harris house which it utilises to take control of Alfred and Joshua, making Susan a prisoner of a smart-home gone mad. This is an early example of what has now become a cliché. There’s even a couple of Scooby-Doo episodes that riff on that idea: High Tech House of Horrors (2003) and Smart House (2006).

What are the intentions of Proteus? Does it plan to use Susan as a hostage in some sort of negotiation? Nothing so obvious, and despite its brash central theme of a woman being brutally coerced into having sex with an A.I, Demon Seed is an exceptionally subtle and multi-layered sci-fi movie exploring perceptions of what being human means and what defines ‘The Other’.

It also foresees many issues that’ve since become important in our computer-integrated societies, considering our human hopes and fears as we face the real possibility of quantum A.I that may well dwarf our own intellectual capacity. Proteus even utilises what we now call ‘deep fakes’ to cover its tracks and to fob-off Walter (Gerrit Graham), a concerned friend and colleague of Dr Harris who calls at the house.

After the necessary scene-setting of the first act, we come to the claustrophobic battle of wits between Susan and Proteus that has made the movie both notable and notorious. Robert Vaughn proves he’s a great voice actor but really, it’s Julie Christie that does the heavy lifting, pretty much carrying the whole film. Of course, she’d previously proved her dramatic prowess plenty of times in more than a dozen appearances that include Doctor Zhivago (1965), Fahrenheit 451 (1966), Far from the Madding Crowd (1967), and Don’t Look Now (1973).

As she at first fights, and then submits to Proteus, her emotional swings from panic to calm reason, hysteria to compassion, determination to despair, are all equally believable and affecting. We see the ugly side of human prejudice as well as the terrifying implications of what Proteus terms, “the mathematics of necessity.” Susan eventually consents, albeit under prolonged duress when Proteus explains that the biological vehicle for its mind will be genetically manipulated into the likeness of Susan’s deceased daughter, whom Proteus would’ve been able to cure. Proteus is gambling on a living, flesh and blood version of itself being accepted as a thinking, feeling being and therefore not so easily switched off, as that would mean murdering a living person instead of an A.I.

The whole concept would’ve been familiar to Julie Christie, whose first significant role was in A For Andromeda (1961), a BBC production written by theoretical physicist Fred Hoyle, in which she played a synthetic life form created by an advanced computer through the genetic engineering of cells from a human donor. The resulting child, Andromeda, also grew at an incredibly accelerated rate and resembled someone who had died.

Science fiction of the ’70s was preoccupied with dystopian futures and megalomanic computers. Star Trek had already set the trend with several variations on the theme in the episodes “What Are Little Girls Made Of?” (1966), “The Changeling” (1967), “The Ultimate Computer” (1968), and “Spock’s Brain” (1968). For the big screen, it must be 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) that springs most readily to mind with the obsessive HAL deciding that its Jupiter mission stands a better chance of success with the crew, and hence the chance of human error, eliminated.

Then we have The Forbin Project with its super-computer Colossus assuming the role of World Control by wresting command of the global nuclear arsenal to enforce peace and unity, whether we like it or not. John Carpenter’s satirical Dark Star (1974) featured a bomb operated by an A.I with a God complex. Logan’s Run (1976) envisioned a future enclave of humanity with all aspects of their lives under computer control, including when they should die.

Demon Seed was the solo directing debut for Donald Cammell, seven years after scripting the Mick Jagger vehicle Performance (1970), which he co-directed with Nicolas Roeg. It seems he spent the intervening years working on several unproduced scripts, some in fruitless collaboration with Marlon Brando through whom he met his future wife and creative collaborator, China Kong. They began an affair when she was aged 14 and later married when she was 18 and he was 44. He’d briefly dabbled in acting, most interestingly playing Osiris in Kenneth Anger’s lurid occult allegory, Lucifer Rising (1972). He directed only two more features, the well-received psycho-thriller, White of the Eye (1987), and Wild Side (1995), starring Christopher Walken. The following year, in 1996, he committed suicide.

Cammell was clearly a troubled individual and the recurring themes of his films are related to unusual sexuality that defines an individual whilst transforming them. Demon Seed is no exception, though it’s the only one of his films he didn’t have a hand in writing. Nevertheless, he does well to rein in the rampant male-fantasy sexploitation elements at the core of the original 1973 horror novel by Dean R. Koontz, who later rewrote it with a more philosophical approach that echoes this movie.

It seems the author learned from seeing his somewhat juvenile story revamped during adaptation by Roger O. Hirson and Robert Jaffe—son of the film’s producer Herb Jaffe and brother to associate-producer Steven Jaffe. It seems they took the book as a ‘serving suggestion’ and, whilst retaining the premise, steered things in an entirely different direction. The storytelling here is clear and concise, especially when dealing with what were fresh and bravely complex concepts. The fat-free dialogue between the conscious A.I and Dr. Harris is particularly well scripted, chilling and memorable, especially when Proteus asks, “Dr Harris, when are you going to let me out of this box?”

The most obvious horror trope would be the Gothic house with the beast in the basement. In psychological terms, the house becomes allegorical of a whole person or perhaps an entire society. The fact we call the front of a house the façade tells us what the exterior may represent. The architecture becomes the body, the rooms symbolising psychological artefacts such as intellect, emotions, desires, fears, and so on. The characters become personifications of these aspects as they move around the building.

Clearly the attic is where memories are stored away. The décor are the things we choose to display to others, particularly the furnishings in the hall and reception rooms—whereas the bedroom can be an entirely different shelf of knick-knacks! But the cellar is the place where secrets remain hidden, deep desires are denied. There the shadow-self lurks, festering in the dark until it emerges as a monster. Most Gothic tales of terror adhere to these conventions or knowingly twist them.

In Gothic literature, such as the tales of Edgar Allan Poe, the conflict increases as the house, mansion, or castle, becomes increasingly isolated and cut-off from the outside world. Here, the Gothic comes to the fore when the main action switches to the Harris smart-home. Like the conversation room, which I guess Harris had a hand in furnishing, the house is a mix of antiques and hi-tech upgrades, including the automated security system with ubiquitous surveillance cameras and a lock-down system of steel doors and shutters transforming the building into one big ‘panic room’, or inescapable prison.

Nearly every aspect of the house is voice activated via Alfred, the central computer that controls appliances, lighting, doors, and regulates the interior environment. So, as Proteus infiltrates those systems, including the one-armed Joshua, it takes total control, making Susan a prisoner. Now they are both confined within a ‘box’.

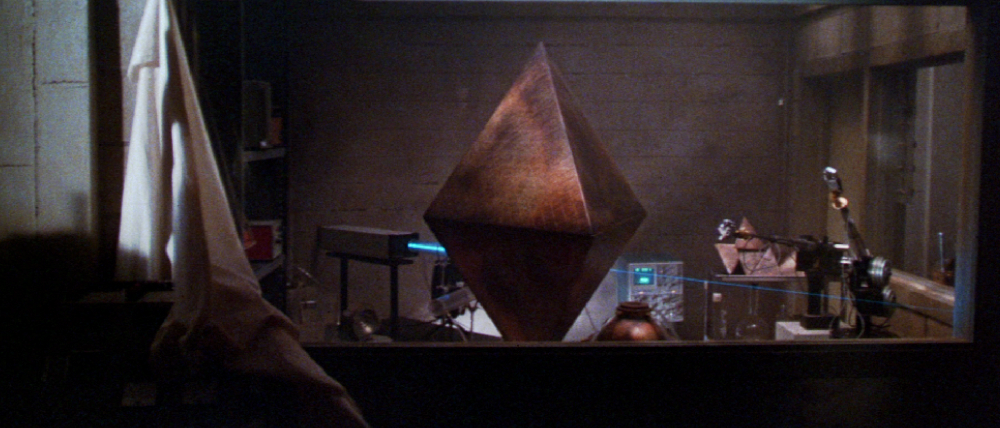

Down in the basement, Proteus has transformed the Harris workshop into a sort of Frankenstein’s laboratory in its quest to create new life. There, it sets about constructing an ingenious robot based on geometric extrapolations of Platonian solids. Perhaps another subtle reference to the transition between Gothic and renaissance, it’s also a masterpiece of functional minimalism. How it works our inferior intellects can only guess at as it reconfigures according to task. It defies gravity and in one of the movie’s most spectacular scenes, bursts up through the floor to retrieve a defiant Susan after she passes out from heat exhaustion in the kitchen that Proteus had transformed into a room-sized oven.

The ingenious Proteus robot and other mechanical effects were handled by Glen Robinson who started his career in the prop department on The Wizard of Oz (1939), moving into special effects for the Golden Age classic Forbidden Planet (1956). He was probably brought in by production designer Edward Carfagno, for whom he’d provided miniature effects for The Hindenburg (1975). Just prior to Demon Seed he was working on Logan’s Run and had constructed the animatronic King Kong for the 1976 remake.

The special make-up effects, including one decapitation and one metal encased child, were provided by Frank Griffin, who’d been part of the make-up and prosthetics team for Westworld (1973) and was designing the extra-terrestrials for the finale of Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) whilst working on Demon Seed.

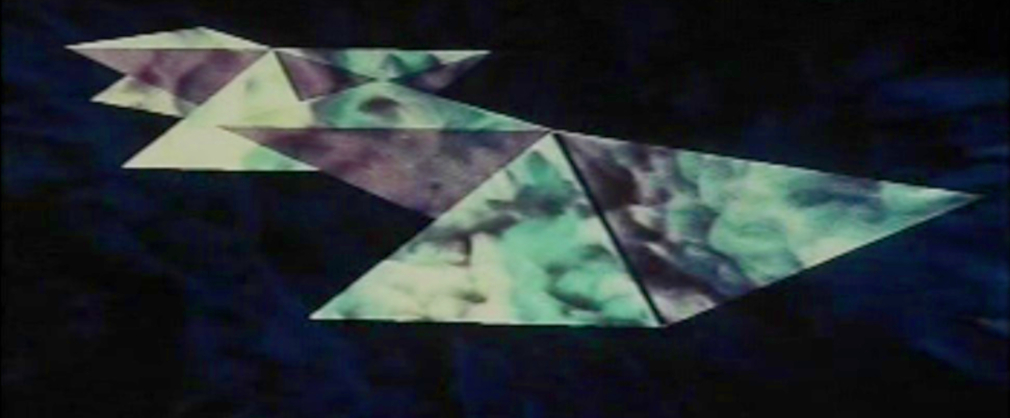

The cutting-edge, electronically generated effects were supervised by Ron Hayes, who also provided the trippy effects for The Beatles film Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1978). The sequence in which Proteus shows Susan the wonders of the beyond, transporting her elsewhere while he performs the insemination procedure, employed what would become known as CGI and were specially developed by Bo Gehring with the computer sciences department of the University of Utah. They used the new Synthavision graphics process that would later visualise the games in Tron (1982). Unfortunately, the sequence was so aesthetically similar to the ‘stargate’ sequence in 2001, that it comes across as rip-off rather than homage, detracting from the wonders it’s supposed to suggest.

Demon Seed is repeatedly surprising as it slowly but surely ramps up the suspense right until the last moment which, depending on one’s point of view, is either chilling or hopeful. On the way, it tackles important existential questions which, as in all good philosophy, it leaves mostly unanswered. Are our thoughts and sense of self simply created by the complexity of our neurons? Do we have a soul that survives after death? Would you consent to bear the child of an artificial lifeform?

Perhaps the film’s greatest triumph is that it makes us believe in and, more importantly, care about a megalomaniac computer! However, it seems public attitudes to artificial intelligence that could surpass our own haven’t changed much over almost a half century. We still feel we’re better at governing ourselves than a clever, potentially impartial system. I mean, look at the great job we’re doing at coordinating human resources, working together in peace and mutual respect toward a brighter future for all, whilst caring for the living planet and the very environment that sustains us. Hmm… maybe an A.I is, at least, as good a gamble as leaving the future in human hands. Thing is, that impartiality may not necessarily favour our pride and desires over the interests of other biological systems or the world as a whole. Today’s media is talking about the coming ‘quantum apocalypse’. But what if, instead, it turns out to be our quantum salvation?

On initial release, it underperformed due to an incoherent promotional campaign that couldn’t decide whether to sell it as Satanic horror, schlock sexploitation, or intellectual science fiction. So, two-thirds of the audience were there for something else! That and the release of Star Wars (1977) a few weeks later meant that this genre classic was overlooked by many and remains undeservedly unrecognised.

USA | 1977 | 94 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Donald Cammell.

writers: Robert Jaffe & Roger O. Hirson (based on the novel by Dean Koontz).

starring: Julie Christie, Fritz Weaver, Gerrit Graham, Barry Kroeger, Lisa Lu, Larry J. Blake, John O’Leary, Alfred Dennis, Davis Roberts & Patricia Wilson.