VIOLENT STREETS (1974)

A retired yakuza is caught in the middle of a growing conflict between two rival clans.

A retired yakuza is caught in the middle of a growing conflict between two rival clans.

If you’re looking for a definitive Japanese 1970s yakuza movie, then Hideo Gosha’s Violent Streets / Bôryoku gai is a good place to start because it brings together several typical tropes of the genre. It was made during a transitional period as cinema audiences were dwindling due to the proliferation of television, which offered plenty of accessible content in the well-worn genres of chanbara (samurai swordplay), jidaigeki (period drama), and kaiju (big monsters), plus the popular terebi dorama (drama series format).

So, Japanese cinema was searching for the next big thing that could coax audiences back. The arthouse niche remained stable but wasn’t lucrative enough to keep the industry going. Offering spectacle with more lavish productions was one way, but those kinds of budgets were rare and generally too risky for a floundering studio system but it didn’t cost that much to offer content too extreme for TV. It seemed sex and violence could be the saviours of the big screen and Violent Streets has both, sometimes at the same time. It’s not for everyone and certainly confounds many of our modern sensibilities.

This trend was reflected globally in the broader crime genre, which was getting grittier, with the likes of Dirty Harry (1971) in the US and Get Carter (1971) in the UK. In Italy’s genre-driven cinema, the clever giallo was making way for the brutal poliziotteschi. In Japan, the popularity of samurai films was waning in favour of their contemporary equivalent: the yakuza.

Battles Without Honour and Humanity (1973), directed by Kinji Fukasaku, changed the trajectory of Japanese cinema, templating an ultraviolent style of gangster film that dropped any romanticised pretence of honour among thieves. Instead of samurai-like heroes struggling with their conscience, torn between obligation or doing the right thing, we have an array of callous hoodlums caught up with the vicious in-fighting of their own gangs, as well as turf wars with rival outfits. Basically, a big excuse for plenty of brutalities. The blockbuster spawned eight sequels through the 1970s, plus two more in the early-2000s.

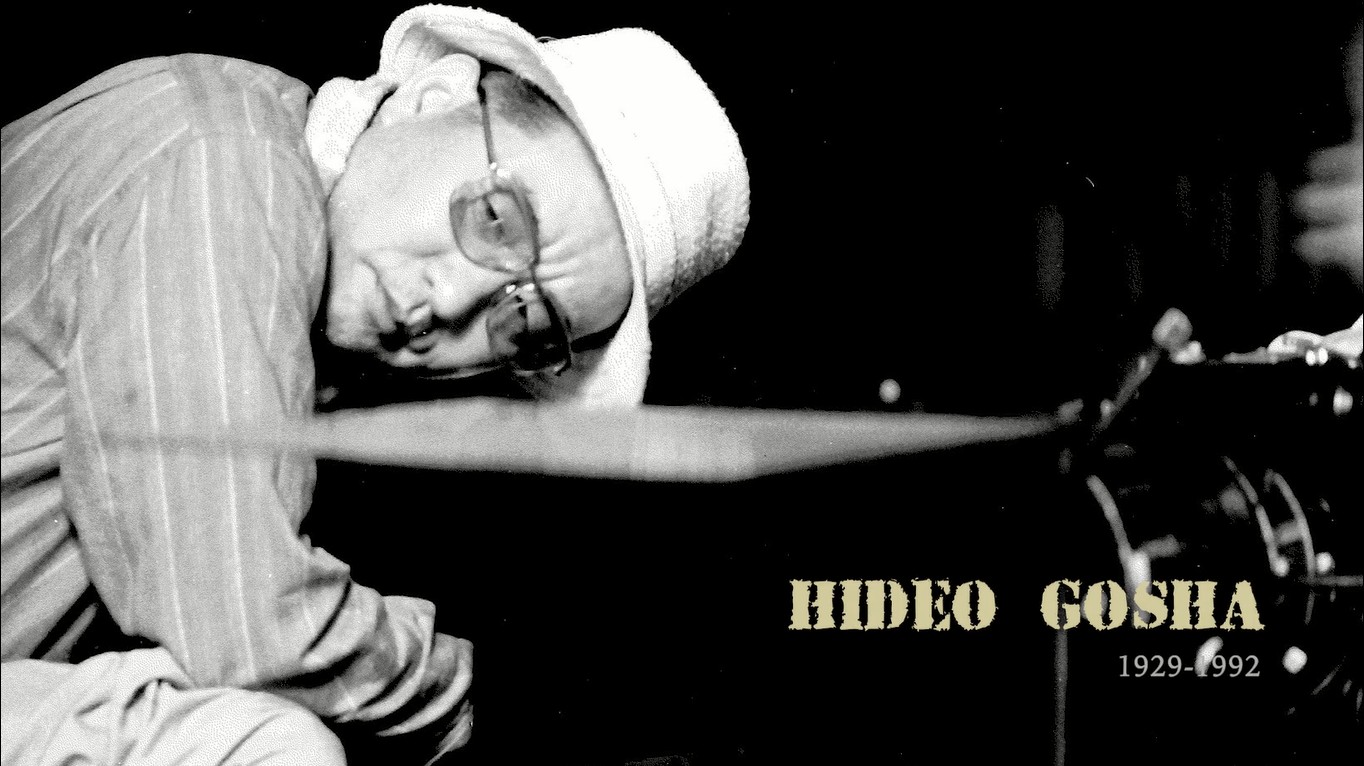

Hideo Gosha was known for superior chanbara since his notable debut feature Three Outlaw Samurai (1964), which had been a cinematic extension of his hit TV series of the same name. He followed this with another eight notable samurai films and a couple of miniseries before Toei studios tasked him with producing a yakuza movie to reflect the shift in audience expectations. Now, the source material for Battles Without Honour and Humanity had been the serialised memoirs of Kōzō Minō, a real-life yakuza who wrote his volatile exposé while in prison. So, to garner comparative cachet, Violent Streets was developed with Noboru Andô in mind for the lead.

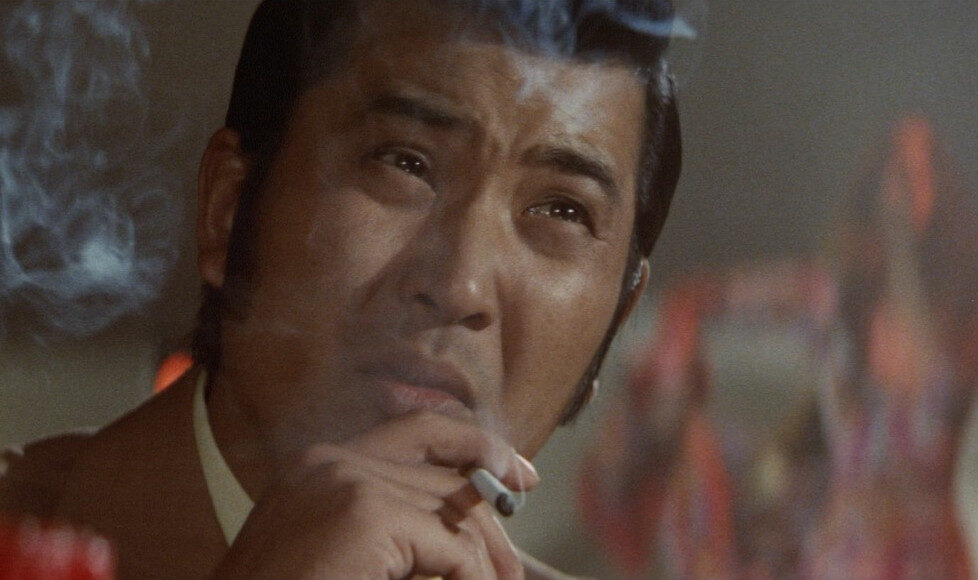

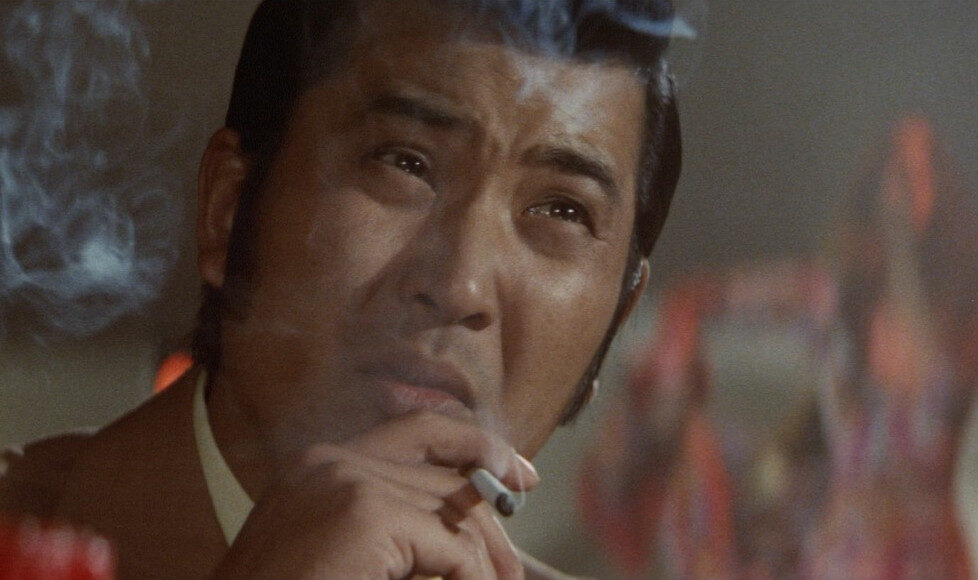

Noboru Andô was already famous for tough guy yakuza roles in nearly 40 films since his debut Blood and the Law (1965), which was based on his memoirs of being a yakuza boss, made a year after his release from prison. At the peak of his power, his gang counted 300 in its ranks and controlled the Shibuya district of Tokyo, operating nightclubs and fronted by legitimate entertainment companies. It seems that reflection during his six-year sentence led him to regret and renounce his life of violence and, after first starring as himself, he pursued a successful career as an actor and singer.

The story of Violent Streets is credited to its director, Hideo Gosha, with a screenplay by Masahiro Kakefuda and Nobuaki Nakajima. Although Noboru Andô isn’t given any writing credit, there are several parallels between his real-life exploits and those of his character, Egawa—an ex-yakuza boss who’s trying to go straight after serving years in prison for his part in gang wars that won the Tokigu ‘family’ a good chunk of Tokyo territory. As recompense, for his sacrifice and for not fingering any accomplices, the gang gifted him the Madrid club—a flamenco-themed bar in the heart of Tokyo. However, it seems they didn’t expect Egawa to run it as a legit business and the gang wants it back because the club has strategic value.

Right from the start it’s fairly clear how things are going to play out—the ex-gangster (or crook, or gunslinger, or black ops agent) is trying to avoid slipping back into their old ways but at some point, approaching the finale, something will push them too far and they just won’t take it anymore. I’m thinking ‘Killer Kane’ in The Ninth Configuration (1980), or John Wick (2014) for a more contemporary example. And, of course, Bruce Banner trumps the lot. Early on, we get a glimpse of how effective Egawa can be when a bunch of hoodlums cause trouble in the Madrid and one of them ends up lobotomised with a bill spike.

The very first, and also the final, images we see in Violent Streets are of dogs, snarling and barking but caged. This is a kind of visual translation of an old adage (attributed to Miyamoto Musashi, author of The Book of Five Rings / Go Rin No Sho, a philosophical text on sword technique) describing the seasoned samurai as having “the hide of an old dog and the heart of a tiger.” Straight off the bat, Gosha is drawing a parallel between the samurai of his earlier films and the modern yakuza. The dogs could also represent Egawa who has been caged, first by his obligation to the gangster code, then behind prison bars, and now by his own past. It’s also a great metaphor for contained rage waiting to break free.

The plot isn’t as complicated as one may think on first viewing. For me, things didn’t start falling into place until the halfway mark. I was having real difficulty working out who was who and which gang they were from. Who hired the duo of deadly assassins, one of whom (Madame Joy) seems to be a kabuki-trained actor specialising in female roles who stick to their transgender, kimono-clad identity off-stage and must kill to remain calm? This level of confusion is probably authentic for the shifting allegiances in the world of the yakuza and is integral to the plot here, with thugs masquerading as members of other gangs to shift blame and precipitate a turf war. Also, the lower ranks are staging attacks on their own gangs and allies to prompt their leaders into more drastic, decisive action. Without giving too much away, it turns out that rival Osaka gangs want to move into Tokyo and the best way to make the local gangs vulnerable is to build mistrust and stoke some in-fighting.

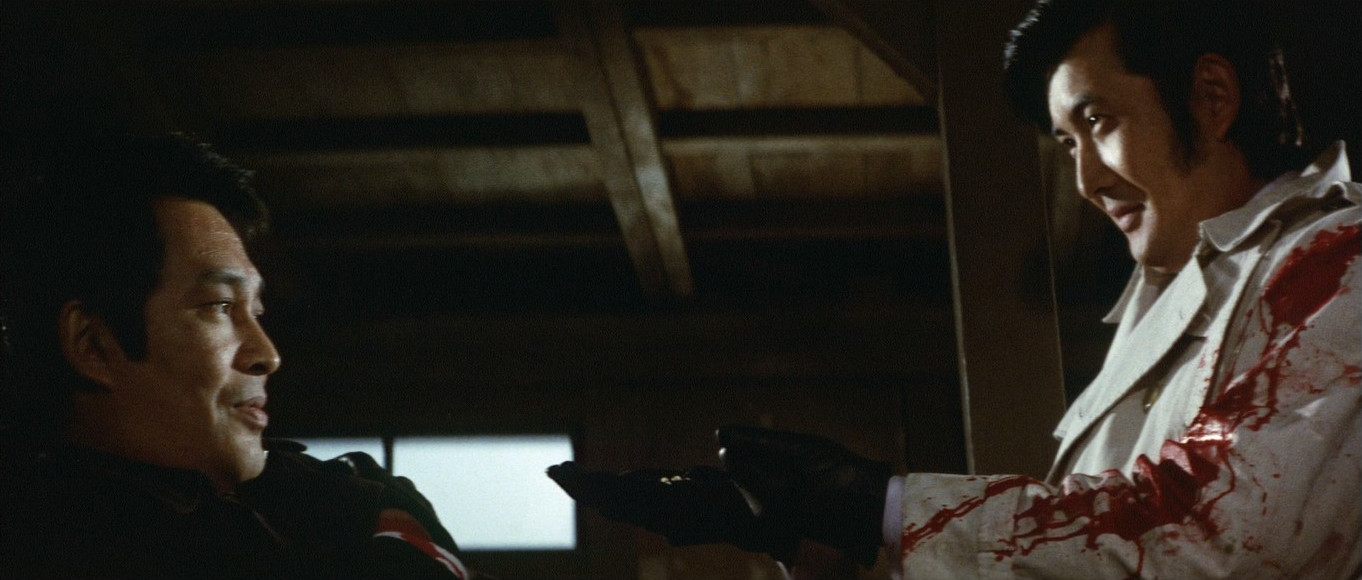

The intended catalyst for a gang war, and also to fund the purchase of weapons, is the kidnapping of Minami (Minami Nakatsugawa), a pop star contracted to a major media company controlled by the Tokigu clan. It all goes tragically wrong and from then on things go from bad to worse as fragile alliances start to crumble. The kidnapping and ransom collection sequences provide some of the most memorable, and in parts truly disturbing, imagery as the gang uses gorilla and horror masks to hide their identities. We do see enough to learn that ‘young punk’ Haruo (Asao Koike) is irredeemable. Unfortunately, he’s the brother of the Madrid’s hostess…

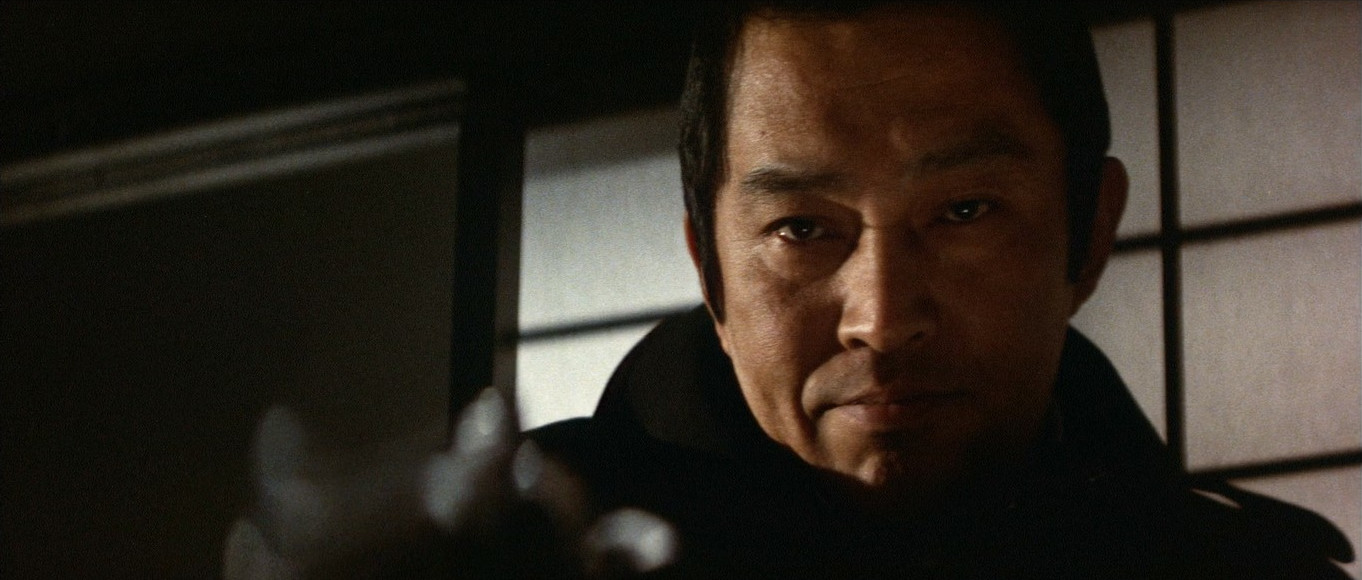

Egawa is under pressure from old accomplices to resurrect his dispersed gang and from others to join with the Tokigu. His old colleague, Yazaki (Akira Kobayashi) would rather work with him than be contracted to ‘remove’ him and the relationship between these two men is the thread that, barely, brings cohesion to the narrative. Their understated, almost deadpan performances are some of the best things about Violent Streets, along with explosions of thrilling brutality delivered with the veteran director’s visually inventive flair. His cinematographer, Yoshikazu Yamazawa, steps up and achieves plenty of creative shots from over, under, or through obstacles – using the rain on windows to distort faces, adding depth by pulling focus between small objects in the foreground to people some distance away, employing art and ornament as narrative touchstones.

Along with much of Japan’s post-war cinema, Violent Streets does have subtext. It serves as a critique of rampant capitalism, economic expansion, and rushed redevelopment of inner cities. In one poignant scene, characters discuss memories of meaningful moments they’ve shared and all of them occurred in places that have since disappeared. Much of late-20th-century Japanese cinema deals with the aftermath of WWII as the nation acknowledges its heritage and reinvents its cultural identities.

The yakuza power structures and machinations are reflected in corruption on a national scale as ex-yakuza use their ill-gotten gains to transition into corporate business, take control of media companies, and enter politics. Power struggle for territories is a kind of fractal pattern that begins with the control of streets by petty thugs, sections of cities by clans, whole regions by yakuza alliances, cities by politicians, and whole nations by governments when those power struggles may manifest as war on a global scale. International politics are even more convoluted and difficult to follow than the plot of a yakuza movie…

Outside Japan, Hideo Gosha’s Violent Streets has been overlooked until now and this Blu-ray from Eureka! Entertainment, the latest addition to their ‘Masters of Cinema’ imprint, lives up to half of its title. The violence is swift, brutal, and bloody, but mostly occurs in the nightclubs, strip clubs, scrapyards, office blocks, and chicken farms of Tokyo… and very little spills out onto the streets. It also offers some edgy, challenging content, complex characters, a well-crafted though fragmented narrative, and exhilarating action delivered with aplomb by an assured director.

JAPAN | 1974 | 99 MINUTES | 2.40:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

director: Hideo Gosha.

writer: Hideo Gosha, Masahiro Kakefuda, Nobuaki Nakajima.

starring: Noboru Andô, Akira Kobayashi, Isao Natsuyagi, Bunta Sugawara, Tetsurô Tanba, Asao Koike, Miyoko Akaza.