THE MASQUE OF THE RED DEATH (1964)

A European prince terrorises the local peasantry while using his castle as a refuge against the "Red Death" plague that stalks the land.

A European prince terrorises the local peasantry while using his castle as a refuge against the "Red Death" plague that stalks the land.

Studio Canal’s release of Roger Corman’s sublime adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Masque of the Red Death, presented on Blu-ray with a 4K restoration undertaken by Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation and The Academy, with funding from the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation, confirms Corman’s legendary status in independent cinema.

After an aborted early career in engineering, Corman started at the bottom and rose to the top in the film industry. His first job was as a runner for Fox, and after later gaining access to their screenwriting department, he became a ‘reader’ wading through scripts producers had little time to look at. After a brief sojourn to Europe, completing post-graduate work in modern English literature at Oxford’s Balliol College, he worked briefly as a literary agent and a television stagehand before selling his first screenplay, Highway Dragnet, to Allied Artists in 1953.

As an associate producer on Highway Dragnet, Corman developed an instinct for making decent films with little money. After a period in which he made a variety of films (westerns, rock n’ roll films, car race thrillers, and sci-fi ‘creature-features’), in 1959 he formed Filmgroup with his brother to produce and release low-budget, black-and-white, drive-in double features on behalf of American International Pictures (AIP), Allied Artists, and other distributors.

Often attributed with creating the horror-comedy genre thanks to A Bucket of Blood (1959) and The Little Shop of Horrors (1960), he was equally enthusiastic about using cinema as social commentary, to voice counter-culture and civil rights concerns. He explored these in the first Hell’s Angels biker film, The Wild Angels (1966), he featured segregation, including an early lead role for William Shatner, in The Intruder (1960), depicted psychedelic drug culture in The Trip (1967), and charted the death of Hollywood celebrity in Targets (1968). New World Pictures, his independent production and distribution company formed in the 1970s, released several cult films, including Boxcar Bertha (1972), Caged Heat (1974), Death Race 2000 (1975), Piranha (1978), Battle Beyond the Stars (1980), and Galaxy of Terror (1981). The ‘Roger Corman Film School’, as it became known, also gave early career breaks to directors such as Coppola, Scorsese, Bogdanovich, Demme, Hellman, and Dante.

Corman developed a fascination for the stories of Edgar Allan Poe in his English classes at school, finding “it was the mystique that got me; things happening on the surface but with something going on underneath.” He returned to Poe for his renowned cycle of adaptations he made in the 1960s, instigated by Corman’s frustrations with making AIP’s double bills:

I was a little bit tired of that. Also, I felt that the sales gimmick of putting two low-budget pictures together was wearing thin at the box office.

Seeing an opportunity to adapt Poe, he persuaded executives James H. Nicholson and Samuel Z. Arkoff to produce one $200,000 colour adaptation of Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher (1960), despite their reservations about the author’s suitability for its established teen market. Corman rationalised that Poe had two audiences—one that respected him as a major American writer, and one that simply loved to be entertained by his tales of the macabre. He believed that, by “working with the unconscious mind” featured in Poe’s stories, with leading man Vincent Price (also something of a Poe aficionado), production designer Daniel Haller, and cinematographer Floyd Crosby, they could achieve a heightened sense of unreality in the films.

Corman had only ever intended to make Usher but, after it grossed over a million dollars over six months, AIP demanded more. He then offered them a choice between The Pit and the Pendulum (1961) or The Masque of the Red Death. However, the latter prospect was complicated. Initially, Corman felt that adapting Masque in 1960, only three years after the release of Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957), would open him up to accusations of copying the great Swedish director because “of course, both The Masque and The Seventh Seal deal with the Middle Ages and in each the leading character confronts Death as an individual.” However, as the decade wore on, his Poe films gradually became more formulaic. By 1963, having exhausted most of Poe’s material and feeling “we were starting to really repeat ourselves”, he turned his attention to Masque as “that and Usher are really his two greatest stories.” Masque was also another opportunity to indulge his love of European art cinema, with the works of Bergman, Hitchcock and German Expressionism having had a huge influence on the Poe pictures. However, getting a good enough script was a struggle.

Corman already anticipated adapting Masque with one his regular screenwriters, Charles Beaumont, during the making of The Intruder in 1960. Despite this, in an initial deal with British documentary company Alfred Wagg Productions, he asked writer John Carter to develop a treatment of Masque, sending him a copy of Richard Matheson’s script for Pendulum for inspiration. Beaumont’s opinion of Carter’s script was that it was “scholarly but dull.” Wagg Productions also rejected the script, Carter was paid off and Corman eventually asked writer-producer Robert Towne and Barboura Morris (a former Corman classmate, with appearances in several of his early AIP films, who worked as his secretary) to submit drafts.

While Towne would go on to write the final film in the Poe cycle, The Tomb of Ligeia (1965), and a successful writing and producing career, his and Morris’ Masque scripts failed to materialise. When Corman returned to Beaumont, who was, by this time, very ill, his first draft left Corman somewhat dissatisfied. Robert Wright Campbell, who had written Corman’s war film The Secret Invasion (1964), came to London and re-wrote it three weeks before Corman was due to start on Masque. With Beaumont having established the central idea of the main character Prospero’s Satanic convictions being tested, Campbell introduced elements from another Poe story, Hop Frog, that Corman felt “gave an additional dimension to the picture.”

Further to this, AIP faced a legal conundrum prior to the start of production in November 1963. Independent producer Alex Gordon, who had made several drive-in features with them, took out an injunction to prevent its release because, he believed, the Masque script he had been shopping around since his departure from AIP in 1959, had been stolen. Gordon alleged he had announced his version first, had tried to tempt Bergman to direct and that Vincent Price had agreed to star. Despite Gordon’s protestations that there were at least “sixty eight points of similarity” between his script and the Beaumont/Campbell draft, the presiding judge rejected the petition. The matter was eventually settled out of court.

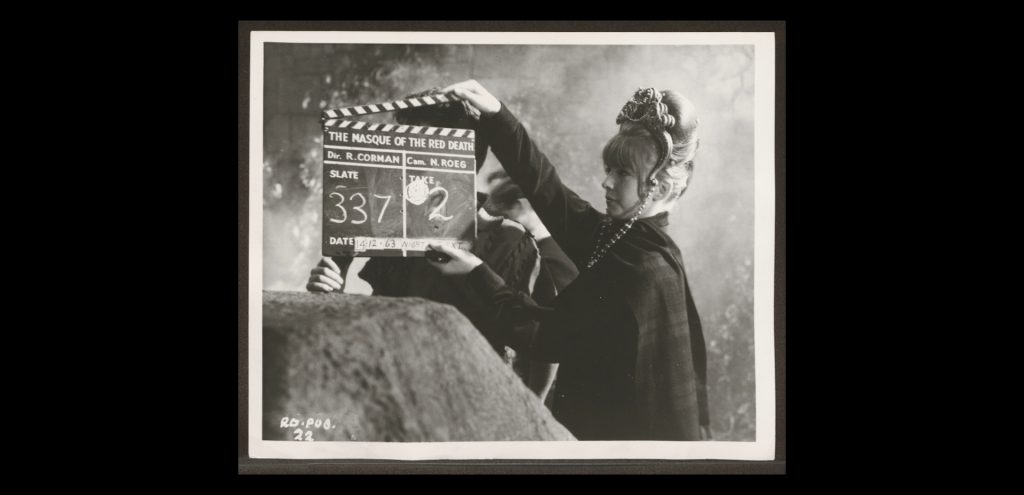

In light of its existing distribution and co-production deal with British company Anglo-Amalgamated, AIP shifted its production of Masque to England’s Associated British Elstree studios in Borehamwood. There it could take advantage of the EADY Levy, a subsidy on cinema admissions that was applied to and supported films made in England. It could use an American director and star but the rest of the cast and crew had to be British to qualify for the Levy. For star Vincent Price, Masque opened a period of creative work in British horror made in England that included such significant films as Witchfinder General (1968), the Phibes films (1971–72) and Theatre of Blood (1973). The film’s production designer Daniel Haller worked closely, in a producer role, with British art director Robert Jones. Floyd Crosby, Corman’s trusty cinematographer, was replaced with the up-and-coming Nicolas Roeg, who had been second unit cinematographer on Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and cinematographer on Clive Donner’s The Caretaker (1963).

After seeing Roeg’s previous work, Corman “felt he could bring a style I was looking for, which was very much of a chiaroscuro, light and dark shadowed picture, with a certain ominous quality to it, and yet, at the same time, a classical lighting style.” Roeg’s striking work on Masque would stand him in good stead, and after performing similar duties on Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 (1965) and Schlesinger’s Far From the Madding Crowd (1967), he directed Performance (1970), Walkabout (1971), Don’t Look Now (1973) and The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)—films that confirmed him as one of the finest directors working in that decade.

As filming in England was less expensive, Corman was “quite happy to go over because it meant we would be able to increase our budget.” Although the pace at which his British crew worked was being determined by union rules, he was able to expand the shooting schedule from an average of three weeks to the equivalent of about four on Masque. Resources were spread further when Corman and Daniel Haller toured the backlot at Elstree and repurposed the discarded sets and some of the costumes from big-budget historical picture Beckett (1964), Paramount’s adaptation of Jean Anouilh’s play starring Richard Burton and Peter O’Toole, and “Dan was able to adapt and build our sets around existing flats that really gave us the best look we had ever had.”

Filming began 18 November 1963 with a company of established and young British actors. Joining Price, “who took the work very, very seriously”, were Patrick Magee, Nigel Green, Hazel Court, Jane Asher, and David Weston. Court, having earned her ‘Scream Queen’ label since working with Hammer, had moved to the US and appeared in two of Corman’s Poe films, The Premature Burial (1962) and The Raven (1963). The highly intelligent Magee “was a brilliant character I had seen in several English films before I met him” and Corman admired “the sense of the macabre” he brought to his performances and his ability “to find strange quirks within the character that he could bring out.” Asher, as a child actor, had appeared in Hammer’s The Quatermass Experiment (1955) and had made appearances in several more films and TV shows before she was cast, aged 18, in Masque.

Corman also recalled that, shocked by Kennedy’s assassination that November, cast and crew observed a minute’s silence during the shoot on the day of Kennedy’s funeral. On a more uplifting note, when Asher asked if she could bring her boyfriend to lunch, as he was traveling from Liverpool through to London, Corman was introduced to Paul McCartney on the set. McCartney casually mentioned “a singing group called the Beatles… and that Friday night was going to be his debut concert. So, I wished him well.” Corman had no idea who they were until the press, witnessing the hysteria that greeted them on one of the London dates on the band’s autumn 1963 tour, labelled it ‘Beatlemania’.

As noted by Kim Newman and Sean Hogan on this disc’s commentary, if you’re familiar with the story or the film, it’s uncanny how it now throws up all sorts of associations with our current COVID-19 predicament. First published in 1842 as The Mask of the Red Death: A Fantasy (revised to The Masque of the Red Death in 1845), it earned Poe the grand sum of $12. Prince Prospero summons “a thousand hale and light-hearted” noble friends to a lockdown in his well-provisioned castle, to protect themselves from the terrible Red Death plague devastating the countryside. With no care for their fellow humans outside the walls of the castle, they intend to remain in isolation until the pestilence has passed.

After six months, to entertain his guests, Prospero throws a masquerade ball “of much glare and glitter” in the seven different coloured rooms situated in the castle’s twisting corridors. The last of these rooms, decorated in black and illuminated in red “was ghastly in the extreme” and no guest would dare enter it. The ball inspires madness, wanton fantasies of disgust, and fever dreams measured out by the hourly chime of a strange clock situated in that black and red chamber. Into this morass of immorality appears a figure, its death-masked appearance mimicking the victims of the Red Death, which causes much consternation among the guests. Prospero, outraged by this mockery, confronts this figure as it proceeds through each of the colourful chambers. When Prospero collapses before the figure and dies, the guests discover that the shrouded figure has no substance and they too succumb to the Red Death which, having visited them “like a thief in the night”, now “held illimitable dominion over all.”

In that Death was Poe’s major obsession, supposedly there are autobiographical elements to his story. The Red Death, where blood oozes from the victim’s pores, may reference the tuberculosis that claimed the lives of Poe’s own wife Virginia, his mother Eliza, brother William, and foster mother Frances. Poe also witnessed Baltimore’s cholera epidemic of 1831. The coloured rooms of the castle suggest a symbolic journey from life to death where the ominous clock in the last room, that literally strikes fear into the guests, represents the passage of time, of slow decay and inevitable death. The film’s script and Haller’s designs certainly align very closely to the visual elements of Poe’s short story.

However, it’s a very short story and Beaumont and Campbell expanded upon it as there were no distinct characters apart from Prospero (Vincent Price) who, in their script, is a worshipper of the black arts. They also added a range of other characters, the villagers Gino (David Weston) and Ludovico (Nigel Green) and Ludovico’s daughter, the Christian and virtuous Francesca (Jane Asher), who are all taken to the castle after their village is torched. After asking his consort Juliana (Hazel Court) to mentor her, Prospero sets out to corrupt Francesca’s devout beliefs, to seduce and initiate her into Satanism. The jealous Juliana is also intent on being bestowed this honour and, hoping to impress Prospero, initiates herself into this marriage with disastrous consequences.

Several related subtexts emerge and support Poe’s story —physical and spiritual purity and corruption, revolution against tyranny, the class distinctions and differing moralities of the ‘working class’ villagers and the decadent, elite Prospero and his corrupt cronies —and Campbell adds elements from Hop Frog, Poe’s revenge tale published in 1849, to the mix. Hop-Frog and Trippetta, two youngsters of restricted growth, are enslaved by a cruel king in the original tale. At a masquerade (Poe seemed to be fond of such parties) the defenceless dancer Trippetta is violently abused by the king after she begs him not to humiliate the disabled Hop-Frog, who has been forced to entertain his guests. Hop-Frog’s revenge on the king and his ministers is to burn them to death after a jest in which he covers them in tar and flax to resemble orangutans. Much of this is transferred to the sub-plot featuring the characters of Hop-Toad (Skip Martin) and Esmeralda (Verna Greenlaw), where the perverted nobleman Alfredo (Patrick Magee), inflicting cruelty upon Esmeralda, is persuaded by Hop-Toad to don an ape costume for the masked ball and meets a similar fiery fate.

While Corman was guided by sketches on his script, better ideas often occurred on the day of the shoot:

I try to be as innovative as I can with the camera without being obtrusive. The camera should function to help tell the story. But within that, you can set a mood. I like to use a lot of moving camera positions, move the actors, move the camera, combined with coverage and as interesting a composition as I can get. A composition in depth.

For the dream sequences during Juliana’s black mass, Corman “did a great deal of planning and those shots were sketched out in great detail. I was using special filters, gels, sometimes distortion lenses and a lot of optical printing afterwards… to get different layers of colour distortion.” While Asher recalls that Corman “just romped through making the film, he was so quick and knew what he wanted”, it was not uneventful. Price, about to address the revelers at the masquerade as Prospero, was “stood up on this dais and I came down the stairs wearing these long flowing capes, and tripped! I fell down and knocked myself out cold!”

Expanding upon Poe’s obsession with death and time, Corman’s film offers an intellectual exercise about faith and the nature of good and evil. Prospero recognises Francesca’s devout Christianity as a challenge to his own sadistic, satanic temperament, making her question her own adherence to the Christian faith. Allied to this is the film’s exploration of the terrible consequences of black magic practice, perhaps only properly attempted previously, as Denis Meikle notes, in British films like Night of the Demon (1957) and Night of the Eagle (1962). Hammer certainly didn’t take on the subject matter until their adaptation of Dennis Wheatley’s The Devil Rides Out in 1968. As a result, the British censor removed all of Juliana’s psychedelic visions of satanic possession from Masque. Yet, another of its bugbears, in the combination of blood and breasts during the frenzied attack of the falcon upon Juliana, was subject to minor cuts.

Prospero and Francesca’s duel of faith is central to the film. When she begs for mercy in the name of God at Prospero’s feet, to spare her father Ludovico and lover Gino, Prospero observes “how innocent you are” as he forces her to choose which of the two men will die as punishment for their insolence. Asher matches Price’s decadence with a performance of great subtlety. Francesca’s virtue is also something that catches the eye of Alfredo who merely sees her as someone to corrupt during the entertainments at the castle. Corruption of the innocent is an underlying theme too, a very Sadeian flavour to Beaumont and Campbell’s script. It’s redolent of The 120 Days of Sodom, De Sade’s “tale of four libertines— a duke, a bishop, a judge and a banker—who lock themselves away in a castle with an entourage that includes two harems of teenage boys and girls specially abducted for the occasion.” While the tastes of the time would have prevented anything quite so outrageous to be represented in Masque, it’s reflected in Alfredo’s drooling over the virtuous Francesca and the doll-like Esmeralda and, later, in the perversions suggested in Prospero’s demand that his party-goers “use your imagination and show me the lives and loves of the animals” as Francesca, all in virginal white, watches in bafflement.

Beyond the handsome production design, the restless, prowling camera and the striking colour photography, Corman busily reinforces his and Poe’s themes. Prospero escorts Francesca, much to the chagrin of his mistress Juliana, through the castle’s many coloured rooms in an attempt to unpick what drives her devotion to Christ. He explains his own devotion to the left hand path as an ancestral desire “to open the door that separates us from our creator” and rejects her “gullible” faith, entreating her to question a benevolent God who oversees a world of war, famine, death and pestilence. While she counters this with ideals of love and hope, Prospero again rejects her assertions with an appropriately existential view: “if a God of love and life ever did exist then he is long since dead. Someone, something rules in his place.” This ‘something’ waits within the last of these rooms, one she is barred from.

Prospero’s testing of Francesca’s “perfect faith” is matched by his overtly pulchritudinous mistress Juliana’s own desire to become a satanic bride, having been “an eager student” who has “held back from the final ceremony.” Enhanced by her sumptuous costumes, Hazel Court’s performance and décolletage brim with licentiousness and jealousy. Prospero sees her willingness to go ahead with the invocation as simply a play for power, Juliana being threatened by the intellectual challenge he finds in Francesca. Juliana’s fate is eventually foreshadowed by the cruelty of nature itself, symbolised in Prospero’s demonstration of falconry that provides Francesca with yet another lesson about her subservience to God and his worship of the Fallen Angel.

But can Prospero offer Francesca more than marriage to Satan and is his elite culture out of her reach? The film suggests he senses something good in her that is above the merely sinful, sensual, sadistic pleasures of the black mass, and a quality in her, one he has since lost, that seeks a purer emotional and intellectual life beyond the blasted landscapes visited by the Red Death. Conversely, Francesca recognises that, despite his uneasy treaty with Satan, here is a man who could offer her this opportunity because as, Jonathan Lampley notes, he is a tragic hero and “still has the potential to be a great man.” There is, as Rampley suggests, a further male-female dynamic playing out in the narrative borrowed from Hop Frog, where Esmeralda’s innocent love for Hop-Toad is secured, by Corman’s ubiquitous use of a purging fire, from the corrupted Alfredo’s desire for what is, in effect, an eroticised child.

Compare this to the security Juliana thinks she will find in her satanic invocation. Court consolidates her performance during these sequences. The sexually charged ritual, where she brands her own breast with a burning inverted cross, gives way to a psychedelic nightmare where she is visited, and ritually slaughtered, by several demonic figures. Clearly, at the time, this combination of black magic, sexuality and horror gave the British censor the jitters but now it’s notable, as Newman and Hogan argue, for its awkward cultural appropriations. It’s a woozy, hallucinogenic vision, operatically scored by British composer David Lee, where her daring to taste “the beauties of terror” reaches a terrible conclusion. Thus Juliana, in a shot framed by the swinging, ticking pendulum, hears a disembodied voice speaking of assassins and destiny, emphasising Poe’s own theme of the inevitability of death, that heralds the falcon’s bloody attack on her. Confirming how good he is in this film, Price views the clawed body of his consort and purrs a diamond of a line: “I beg you do not mourn for Juliana. We should celebrate. She has just married a friend of mine.”

Prospero also belatedly realises that his downfall lies in his own ‘marriage’ to the Lord of the Flies. In the film’s climax, he chases Poe’s uninvited red robed figure, who he mistakenly believes is his satanic master, through the bacchanalian revelries in the castle. In a confrontation meted out by the swaying clock pendulum (itself a visual nod to the swinging blade of Corman’s The Pit and the Pendulum), he finally understands that Satan and his powers have no sway against the Red Death. Again, there’s a tragic quality to the character, underlined in his final request that the Red Death spare Francesca, to save the light of this one remaining life. She tenderly kisses Prospero’s cheek in response, acknowledging his brief show of mercy. A great final touch is Prospero tearing off the Red Death’s mask to reveal his own face looking back at him as, according to the Red Death, “there is no face of death until the moment of your own death.” It anticipates the climax to Patrick McGoohan’s surreal TV series The Prisoner (1967-68).

The film’s suitably baroque climax features a writhing sea of Prospero’s revelers being struck down by the tubercular blood splashes of the Red Death’s passage through their ranks. Corman and Roeg’s camerawork and cutting for this sequence befit the psychedelic visual overtones seen throughout the film. It’s perhaps let down by some underwhelming choreography for the crowd scenes, a factor Corman felt was a result of deciding “not to pay extra mandated union fees for going over a day at Christmastime. I still feel that would have made the large-scale ball sequence —with dozens of extras, plenty of fire and lots of action —a true tour de force instead of a merely good sequence.” It ends on a stylistically poetic note, with Prospero succumbing to the pestilence after Francesca, Gino and a few others have been spared from the apocalypse while Death’s global messengers, each robed in the colours of the castle’s chambers, arrive to assess the survivors of what is, presumably, mankind’s oblivion.

Critically, the film’s poetic stance stood it in good stead and its reputation as one of Corman’s best films is maintained to this day. The Monthly Film Bulletin of August 1964 generously praised “an uncommonly intelligent script which probes the concept of diabolism with considerable subtlety” in which “Price conveys a genuine philosophical curiosity as to the unknown territories into which his quest for evil may lead him.” Even from a contemporary viewing its hard to disagree with its assessment that the film sets out to create a world where the concepts of good and evil “are ideas to be tested and found wanting.” It’s noticeable that, in acknowledging the film’s sumptuous look, the Bulletin cited the influence of Italian horror cinema on Corman’s film rather than the then current Hammer films. Certainly, the visual influence of director Riccardo Freda’s Dr Hitchcock films and, to an even greater extent, Mario Bava, links back to AIP’s own distribution of Bava’s films in the US and Corman’s appreciation of European cinema.

UK • USA | 1964 | 89 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • LATIN

The restored and extended The Masque of the Red Death is out on DVD, Blu-ray, and digital from 25 January 2021 in the UK.

The restoration presented here includes Corman’s full cut and the UK theatrical cut. Previous cuts/versions, including only some of the material excised by both UK and US censors, have been released on DVD, Blu-ray, and seen via BBC broadcasts. This film was, it seems, shot in Technicolor’s Techniscope format. It was a cheaper way to shoot a picture in scope using a 35mm process that squeezed the 2.35:1 image, using anamorphic lenses, into a standard 1.37:1 frame. These spherical lenses could produce a fish eye, concave effect on the picture and, in most instances, the image was cropped to reduce it. It’s a noticeable effect on this restoration of Masque, especially at the edges of the frame where figures become tall and thin, but is not overtly distracting.

Techniscope images also tended to look a bit grainy but it’s handled well here. Grain is present, as it should be, but is not detrimental to the impressive picture quality. In some scenes the focus briefly pops in and out and picture quality drops. This seems to be inherent to the prints used to restore the film, presumably occurring during shooting or processing. Despite very minor niggles, this superb restoration glows with colour and texture, particularly in the presentation of the film’s gorgeous lighting, costumes and sets. A feast for the eyes.

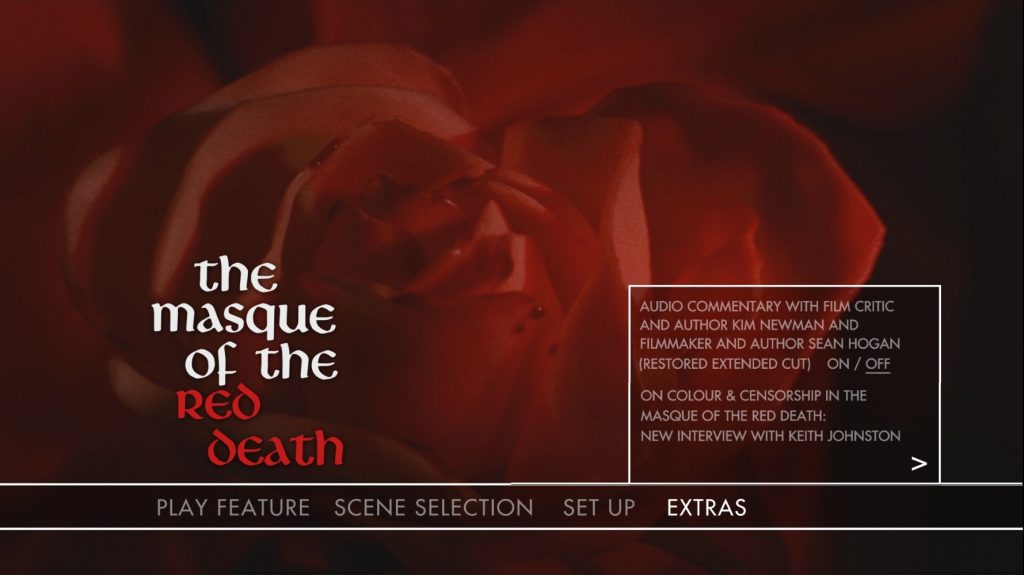

It’s a shame that the ‘Behind the Masque’ Corman interview on MGM’s 2002 ‘Midnite Movies’ DVD didn’t get ported over to this release. Shout Factory’s 2020 Blu-ray also boasts two audio commentaries that were exclusive to that release. However, there are some treats to be found here:

director: Roger Corman.

writers: Charles Beaumont & R. Wright Campbell (based on the novels ‘The Masque of the Red Death’ and ‘Hop-Frog’ by Edgar Allan Poe).

starring: Vincent Price, Hazel Court, Jane Asher, David Weston, Nigel Green, John Westbrook, Patrick Magee & Paul Whitsun-Jones.

I am indebted to the following sources: Pawel Aleksandrowicz, The Cinematography of Roger Corman (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016) • Chris Alexander, ‘Corman in the House of Poe’ interview and ‘Sweet Jane’ interview, Fangoria #311 (March 2012) • Roger Corman ‘Beyond the Masque’ interview, Midnite Movies DVD (MGM, 2002) • Roger Corman, How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime (De Capo, 1998) • Larry French, ‘Vincent Price —The Corman Years’ interview, Fangoria #6 (June 1980) • Lawrence French, Price on Poe, Cinefantastique Vol. 19. 1/2 (January 1989) • Jonathan Malcolm Lampley, Women in the Films of Vincent Price (McFarland, 2011) • Mark Thomas McGee, Roger Corman—The Best of the Cheap Acts (McFarland, 1988) • Will McMorran, ‘The most impure tale ever written’: how The 120 Days of Sodom became a ‘classic’, The Guardian (7 October 2016) • Denis Meikle, Vincent Price —The Art of Fear (Reynolds & Hearn, 2003) • Constantine Nasr (ed), Roger Corman: Interviews (University Press of Mississippi, 2011) • Jonathan Rigby, English Gothic (Signum, 2015) • Philip Van Doren Stern (ed), The Portable Poe (Penguin, 1981) • Tom Vallance, ‘Alex Gordon: Obituary’, The Independent (5 October 2013) • Tom Weaver, A Sci-Fi Swarm and Horror Horde — Interviews with 62 Filmmakers (McFarland, 2010)