THE CITY OF LOST CHILDREN (1995)

A scientist in a surrealist society kidnaps children to steal their dreams, hoping that they slow his ageing process

A scientist in a surrealist society kidnaps children to steal their dreams, hoping that they slow his ageing process

Before the international success of Amelie (2001) put him on the map, French director Jean-Pierre Jeunet made a duology of darker, harder-to-digest films with co-director Marc Caro. The first of them, the well-remembered Delicatessen (1991), was a bleak but imaginative story of murder and cannibalism; while their second outing was a stranger and less successful grown-up fairy tale of nightmares, giants, and talking brains. The City of Lost Children / La cité des enfants perdus doesn’t make much sense, but the directors seem so invested in their hand-crafted wonderland that cohesiveness was clearly the last thing on their minds.

Instead of a traditional story, we instead get somewhat disjointed peeks into a world filled with striking custom-built ideas. There are steampunk contraptions that work with Rube Goldberg-esque precision, clones who behave like Jeunet and Caro’s twisted idea of the seven dwarves, and infectious fleas that bounce around in then-cutting-edge CGI from one host to another. And the whole thing begins with the most dreamlike, fairy tale notion of all.

It’s Christmas Eve and a small child sits waiting in an idyllic room filled with wind-up toys and a snowy window. It’s all a bit too exaggerated, a little too uncanny and sickly sweet to be charming… so we know something not so pure is happening underneath the surface. Soon, a bevvy of terrifying-looking Santa Clauses emerge from the chimney, all identical skinny old bald men doing a quasi-pantomime performance to try and win over the child. Naturally, he cries in terror. Jeunet and Caro seem to be laughing at the very idea of wholesomeness, flipping the most beloved Saint in history to reveal just how quietly horrifying it is to be watched all year round… especially when you’re sleeping.

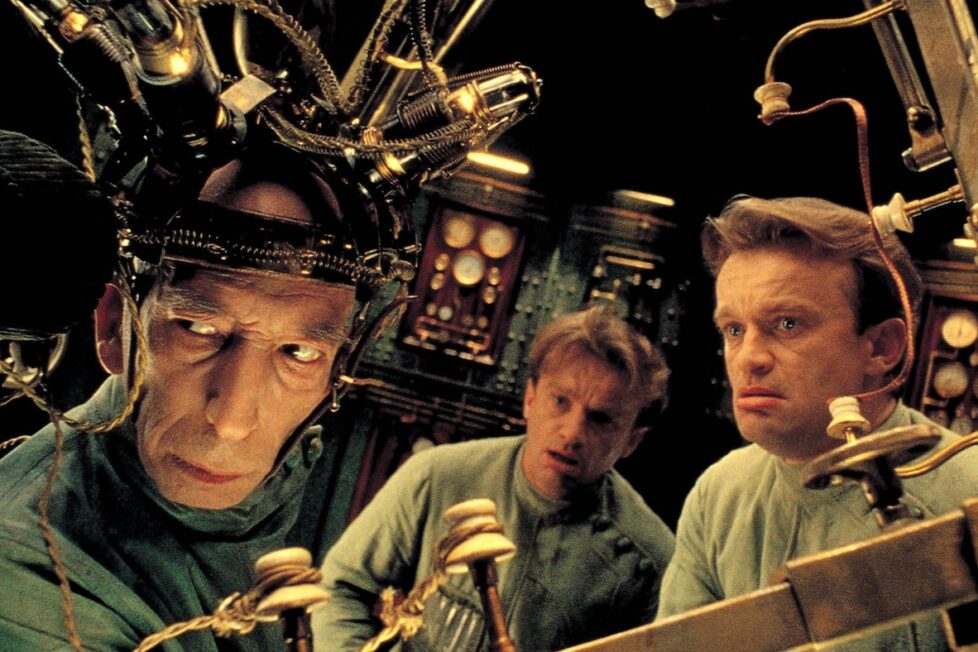

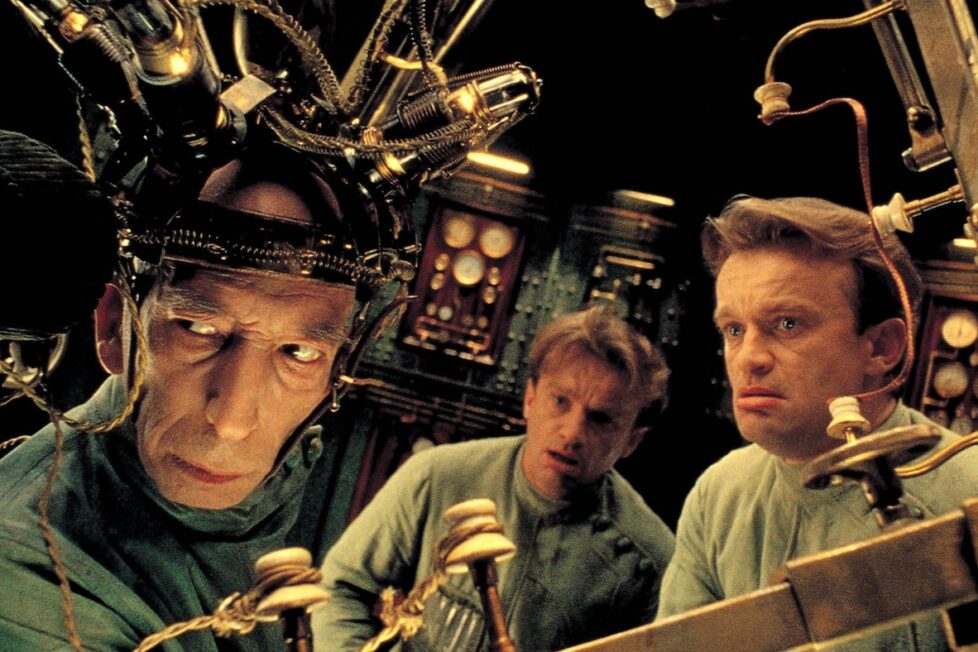

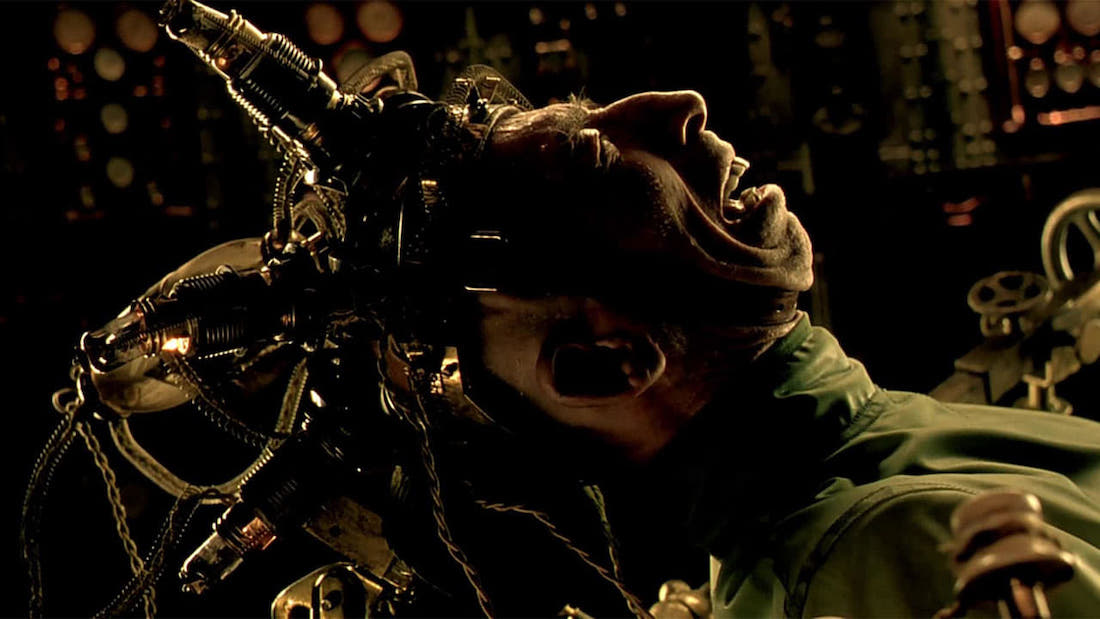

It’s just a dream, of course. The Santa in question is Krank (Daniel Emilkfork), the creation of a mysterious scientist who works in a lab on an abandoned oil rig. The creation can’t dream and, as a result, is ageing rapidly and has thus resorted to stealing children’s dreams. But he’s not so good at appearing in their dreams, as they always turn to nightmares when he appears. Dominique Pinon plays the several dim-witted clones of the mysterious scientist, while Mireille Mosse plays Martha, another of the scientist’s creations. Rounding it out the rag-tag bunch is a talking brain in a fish tank, Uncle Irvin (voiced by Jean-Louis Trintignant). It’s baffling, not least because the directors throw us in at the deep end and spend little time explaining the world we find ourselves in.

This approach can work. For example, the barnstorming opening to Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) and the sheer amount of information delivered in the opening minutes, and the alertness necessary to pick up on all of it. But in The City of Lost Children, this world-building quickly grows frustrating, with whimsy largely taking the place of emotion, so the truly brilliant visuals rarely communicate much besides a kind of quirkiness that worked better in Delicatessen. That’s not to say the film leaves one completely unmoored, as there’s an attempt to get you to grips with what’s going on. And things improve greatly once we start spending time with a character simply named ‘One’ (Ron Pearlman, in a relatively wordless role of broken French).

One’s a strongman and a showman, bursting out of chains in the city’s streets, surrounded by dirty canals and sky-eclipsing blocks of flats. The waters are green, the bricks orange, so it all has a sickly effect on audiences. But here in the middle is red-headed One, a kindly and sweet bedrock that offers the film heart and warmth. Soon, his little brother’s kidnapped by a gang called the Cyclops, a bunch of miscreants who wear metal eyepieces and steal children for Krank and his dreams. This isn’t properly explained in the film and it can be frustrating trying to figure out who is after what and why. But nonetheless, his brother is gone and One’s on the hunt for him, which makes up the strongest part of the film.

Pearlman plays One with open-hearted kindness and the kind of gentle-giant qualities that are the stuff of childhood daydreams. His expressive face is immensely moving, and when photographed next to Crumb (Judith Vittet), a fellow orphan with whom he teams up, he looks truly gigantic

This kind of playfulness with the camera and perspective is some of the strongest points of Jeunet and Caro’s work. Though CGI does sneak in, there’s a Lumiere-like whimsy to the practicality of it everything. The impressive sets are truly mind-boggling and each gadget is brilliantly designed and realised. The mechanical chairs that Krank and co sit in for the dream extractions look something like the seats in the nebuchadnezzar in The Matrix (1995), while the malleability of their camera sees it flying through keyholes and following characters along the seabed. It looks a bit like a manic version of a David Fincher film (and in fact, Se7en shares a cinematographer with this film). Though it was similarly frustrating to City of Lost Children, it’s little surprise that Hollywood scooped up Jeunet for Alien Resurrection (1997) two years later.

Though the blossoming sibling relationship between One and Crumb is lovely (they call him a radiator for the warmth he gives off; she cuddles close to him on empty potato sacks as they set off to infiltrate the oil rig), the directors always keep an edge of violence and malice at play, a truly dark undercurrent that provides a necessary bug in the icing. This provides a nice parallel with another of the film’s strongest elements. Krank, for all his nightmare-inducing weirdness, isn’t a detestable character, but rather someone who’s been made and is trying to find his purpose in life. By stealing the dreams of kids, he just wants to be like they are… but he’s unintentionally frightening and that creates a nice reflection of the way the director’s films together work. Could they ever make a film that was beloved by kids? Could they ever make a film beloved by all kinds of people? Could their ideas of dreams ever be anything but nightmares to other people?

It recalls Wes Anderson’s later masterpiece, The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), which worked on one level as a deconstruction of the kinds of stories he tells as a director, getting to the very heart of why he makes them in the first place. And here, the directors seem to be asking why they can’t seem to stop freaking us out. Or, perhaps, why would they want to stop freaking us out? Grimm fairy tales are horrifying. But contrary to popular belief, kids like being frightened in a safe environment. What could be more perfect for this desire than film? No, The City of Lost Children isn’t a film for kids, but it’s one that stirs up that childhood fear that comes from witnessing a strange world one can’t make sense of. Caro and Jeunet seem to be asking why you’d ever want to pass up that fear and instead settle on something mawkish or, even worse, boring.

The City of Lost Children may be flawed and fractured, but it’s never boring. And any given frame offers the sense of scope, imagination, and uniqueness the directors possess. It’s a truly singular visual aesthetic that’s hard not to admire, even if you don’t love it. It’s just a pity the story around it doesn’t hold together, especially when it’s such a narratively-driven film. In its heart is a spark that works and it comes frustratingly close to turning that spark into something more. But even if it does feel like an ambitious failure, the film is so crammed full of ideas that there are gems to be savoured within; whether that’s One and Crumb, or the barminess of Dominique Pinon’s performance(s). It’s a movie that almost demands a second watch because, flaws aside, there are treasures to be extracted and some fly by so fast one only notices them on a second viewing. Such is the care and attention to detail of Jeunet and Care. If only there were more directors like them.

FRANCE • GERMANY • SPAIN • BELGIUM • USA | 1995 | 112 MINUTES | COLOUR | FRENCH • CANTONESE

This new 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray release from StudioCanal looks absolutely stunning. Jeunet’s films benefit greatly from a definition high enough to capture every little detail, and that’s certainly true of this film. Every trinket, background gag, and vibrant colour pops with clarity and boldness, and the soundtrack too sounds clear and pristine.

The extras are minimal, but what’s there is interesting. The interview with Jeunet is particularly intriguing and the behind-the-scenes footage is essential—if not as in-depth as one would expect from a re-release such as this. Overall, however, it’s a strong package, with the film rightfully taking centre stage. It’s never looked better, and it’s hard to imagine any film from almost 30 years ago looking as good as this does.

directors: Marc Caro & Jean-Pierre Jeunet.

writers: Gilles Adrien & Jean-Pierre Jeunet.

starring: Ron Perlman, Daniel Emilfork, Judith Vittet, Dominique Pinon, Jean-Claude Dreyfus, Geneviève Brunet, Odile Mallet, Mireille Mossé, Serge Merlin, François Hadji-Lazaro, Rufus, Ticky Holgado & Jean-Louis Trintignant.