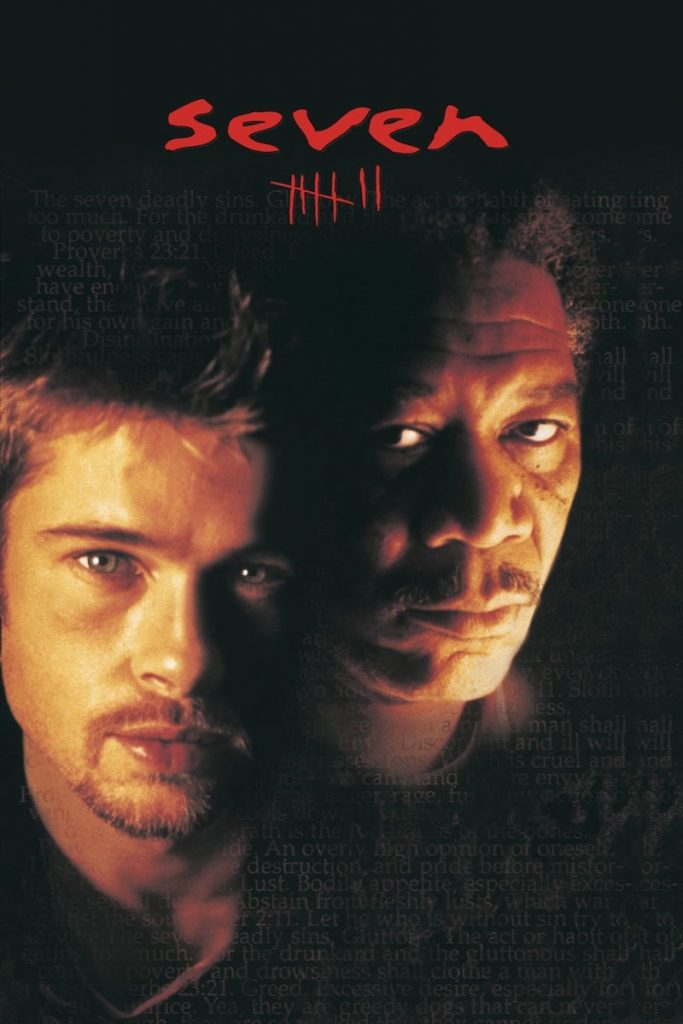

SEVEN (1995)

Two detectives hunt a serial killer who uses the seven deadly sins as his motives.

Two detectives hunt a serial killer who uses the seven deadly sins as his motives.

The star of David Fincher’s Se7en isn’t Morgan Freeman, or Brad Pitt, or Kevin Spacey: it’s darkness. The darkness of its mood… the overcast darkness of the city where it takes place… the darkness of the squalid interiors where tortured bodies are discovered… and the darkness of the serial killer’s soul.

The villain, seeing himself as an avenger of sin, would argue the same darkness is shared by all the souls in the city–and weary detective William Somerset (Freeman) seems to agree. The only dissidents who believe the world can still be made a good place, are younger cop David Mills (Pitt) who’s been assigned to work with Somerset and, most importantly, his wife Tracy (Gwyneth Paltrow).

But it’s the city and its semi-derelict buildings that dominate more than any character. Somerset, charged with showing new arrival Mills the ropes, is incredulous that he’s voluntarily moved to this place (“you actually fought to get reassigned here?”) Even when the movie finally leaves the urban area for its climax, its surroundings are revealed as unattractive scrappy pockmarked land; neither lush nor desert, marred by intrusive structures.

This city is never identified, though it has characteristics of both New York (first-time screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker conceived Se7en after an unhappy time there) and, in terms of the surrounding countryside, Los Angeles (where it was filmed). But it’s nowhere and everywhere, existing outside of time as well—1950s/1960s-style newspaper front pages are seen on a newsstand, yet the police station uses modern computers.

The metaphorical intention of Fincher and Walker in creating these ambiguities is clear—Se7en should be seen as alluding to the brutality and despair of life in many places and at many times—but they also serve an essential purpose in disorienting the viewer, and this approach extends throughout the film.

It can’t be only the weather that accounts for the extremely dark interiors as well as exteriors (their shadows intensified by the use of a bleach bypass film process). Often it’s not entirely clear what’s happening, how spaces relate, even what objects we’re looking at. The unsettling opening credit sequence, with its shattered typography and flashes of printed and handwritten texts (culminating in a US banknote from which the word ‘GOD’ has been cut out), forewarns us that the straightforward meanings we might normally expect from a Hollywood movie aren’t always to be found here. Sometimes things occur or are seen in Se7en which give the impression they’re significant, yet it’s difficult to fathom what their significance is.

But this feeling that nothing makes much sense is more a matter of the film’s ambience than its overt narrative, which is both clear and (relatively) conventional. The old cop/young cop pairing, argumentative at first then warming into friendship, is very familiar, as is the progress of the plot. Somerset’s the first detective to see that two apparently unconnected grisly murders are linked and they have a serial killer on their hands. There’s some clever clue-finding, an episode where the suspect narrowly evades apprehension, and of course more bodies. Eventually, things get personal for one of the detectives, and there’s a final showdown.

In lesser hands, Se7en might have been a trite genre exercise, notable only for the extreme sadism of its crimes (we only glimpse the results, but the mere ideas are so horrifying that the film feels abominable). Yet Fincher and his team—notably designer Arthur Max and cinematographer Darius Khondji, as well as the actors—lift it far above that with their careful crafting of every detail.

Some of it’s very subtle, almost qualifying for Easter Egg status. For example, the numbers included in the story: Somerset and Mills work at the 14th Precinct (likely representing the seven days before Somerset’s retirement plus the Seven Deadly Sins on which the murders are based), Mills receives the phone call summoning him to the first crime scene at precisely seven minutes into the movie, and so on. There’s also more wit in Se7en than one might expect or remember (Somerset reads Dante’s Divine Comedy for clues, while Mills makes do with a dumbed-down student’s guide), and very occasional moments of contentment (all of them involving the Paltrow character).

For the most part, though, the filmmakers never allow audiences to escape the burden of the gloomy city and its apparently unstoppable tsunami of violence, and it’s this sense of being trapped in an awful world (rather than the characters or plot developments) that gives Se7en much of its power.

Lighting (or its absence) has much to do with this, too, as often true in Fincher’s films. Somerset’s apartment feels sickly and jaundiced; the corridor of the killer’s apartment building glows putrescent green, while the red bulbs inside his home and the extremely red lighting of a brothel where one of the murders takes place suggest that hell’s all around us. Again, it’s notable that the lighting setup in the apartment of Mills and his wife is much more natural and pleasant; it’s as if they, newcomers to the city, haven’t been infected by its wickedness yet. At one point we see Paltrow lying on their bed, caught in a rare shaft of actual sunlight.

While lighting, photography, and visual design provide the atmosphere, Pitt and Freeman craft individuals we can relate to sufficiently that the movie never becomes a swamp of misery. They’re the customary contrasting cops: Mills is cocky, Somerset is quiet, Mills is idealistic, Somerset is disillusioned by other’s apathy in the face of iniquity (though by the very end, perhaps Mills has persuaded him not to be). Mills drinks beer, Somerset wine. Somerset is the intellectual, Mills says “I feed off my emotions”. But despite their differences and their initial clashes, they’re brought together (in one of the movie’s smartest touches) by the nastiness of the city. When Somerset visits Mills and Tracy for dinner, they end up laughing about the infuriating subway train that runs so close to their apartment.

I can’t say too much about why this scene is so resonant because, for those who haven’t seen Se7en, it’ll spoil the impact of the famously bleak and shocking ending. Suffice to say that this dinner is one of the few islands of optimism in the movie, making it clear that the goodness of people like Mills and Tracy can still rise above the terrible conditions (both physical and moral) of the city and can still encourage those who have almost given up, like Somerset.

Paltrow invests her relatively small part with a convincing mild sadness; regretting having moved to the city already, but resigned to making the best of it. Also impressive in another even smaller role is Richard Schiff as a lawyer. But the third main role after Pitt and Freeman is, of course, that of Kevin Spacey as the serial killer (not really a spoiler), usually referred to as ‘John Doe’. Spacey is chilling and mesmerising, meekly compliant and utterly self-assured at the same time. His head is shaven like a monk’s (the actor’s idea) with just a touch of Nosferatu ears, while his speech is flat and affectless until he finally explodes in emotion when Mills remarks that his victims were innocent.

No, says Doe, they were immoral and corrupt, and it’s evidence of the way Se7en so successfully immerses us in its world that even while we’re appalled by the details of his crimes, one can’t help feeling he has something of a point, too. (Indeed, Somerset’s perspective is not so far from Doe’s, though Mills seems to find him incomprehensible. Again, a hint that the important distinction in Se7en is not between law enforcement and law-breakers, but between those who belong to this city and those who don’t.)

Se7en was a major hit, making it into 1995’s box office Top 10, although it gained only one Academy Award nomination (for film editing). Critical reception was generally positive, too. Roger Ebert found it “a dark, grisly, horrifying and intelligent thriller” representing “filmmaking of a high order”, although he also noted that it “misses greatness by not quite finding the right way to end”. (He was right. Though for the most part Se7en is perfectly paced, there’s a rather weak and anticlimactic coda tagged on at the end, a result of studio pressure.)

Sight & Sound’s John Wrathall considered it “the most complex and disturbing entry in the serial killer genre since Manhunter”. Praise wasn’t universal, though. Janet Maslin in The New York Times was scathing about Se7en, calling it “dull” and saying “the whole film has a murky, madly pretentious tone” while Pitt was “demonstrating the eighth sin by frittering away an enormously promising career.”

Freeman was already a noteworthy star (not least thanks to the previous year’s The Shawshank Redemption) and Pitt was on his way to becoming one, having been widely acclaimed for his work in Legends of the Fall (1994). But the career really made by Se7en was David Fincher’s. After starting out in commercials and music videos, he’d only directed one previous feature, the mediocre Alien³ (1992), yet after Se7en he’d go on to make a string of well-received movies.

Indeed, many of Fincher’s themes can be seen in nascent form in Se7en: the savagery and grime of Fight Club (1999), the relationship between an older and a younger man in The Game (1997), and the emphasis on relentless time in The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008). In Se7en, Somerset keeps a metronome by his bed, ticking away the seconds to retirement, or perhaps death. Fincher also revisited the idea of a serial killer fascinated by texts in the factually-based Zodiac (2007), a film as fine as Se7en, and it may even be not too much of a stretch to see some parallels between Se7en’s Doe and Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network (2010), as both are ruthless and creative loners.

All the same, these are only resemblances. None of Fincher’s movies is close to any others of his, and there are few films by any director that comes close to the effect he creates in Se7en. Although superficially it is a noirish police thriller riding on the serial-killer boom post-The Silence of the Lambs (1991), with which Se7en shares a composer in Howard Shore—in truth, it’s a horror film. Never mind that Doe, with his opaque background and his single-minded dedication to the obscene, could plausibly be supernatural anyway. The real horror lies not in the murders, but in the everyday existences of this city’s people.

Mills asks the manager of the brothel: “Do you like what you do for a living?” The reply is “no, I don’t. But that’s life, isn’t it?” He’s abandoned hope.

Morally, so has nearly everyone in Fincher’s city of darkness. At their final confrontation in its hinterland, Mills and Doe still believe, in their different ways, that they can do something to redress all this evil. But only one of them can win and we already know, surely, that it won’t be the good guys.

USA | 1995 | 127 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: David Fincher.

writer: Andrew Kevin Walker.

starring: Brad Pitt, Morgan Freeman, Gwyneth Paltrow, Kevin Spacey & John C. McGinley.