THE MATRIX (1999)

A computer hacker learns from mysterious rebels about the true nature of his reality and his role in the war against its controllers.

A computer hacker learns from mysterious rebels about the true nature of his reality and his role in the war against its controllers.

The last Keanu Reeves-starring cyberpunk movie was Johnny Mnemonic (1995), so one can forgive audiences for being suspicious of The Matrix. In the late-1990s, anticipation was building for George Lucas’s long-awaited return to Star Wars for Episode I: The Phantom Menace (1999), but the lesser-known Wachowskis would instead “free our minds” by offering a glimpse of 21st-century filmmaking.

The Wachowskis wrote The Matrix as part of a screenplay deal with then-President of Warner Bros., Lorenzo di Bonaventura, after impressing him with their script for Assassins (1995). Richard Donner (Lethal Weapon) got to make that movie, but the Wachowskis were allowed to direct their next script in order to prove they had filmmaking talent. Bound (1996) was a neo-noir crime thriller starring Jennifer Tilly and Gina Gershon as lesbian criminals, and its critical success meant the Wachowskis got approval to make their most ambitious script: The Matrix. But only after hiring comic-book artists Geof Darrow and Steve Skroce to draw a 600-page storyboard of the entire film. It was the only way to adequately explain what the finished product would look like. Bound cost a modest £6M to make, but Warner Bros. was so impressed by the Wachowskis’ vision for The Matrix they agreed to give them $66M.

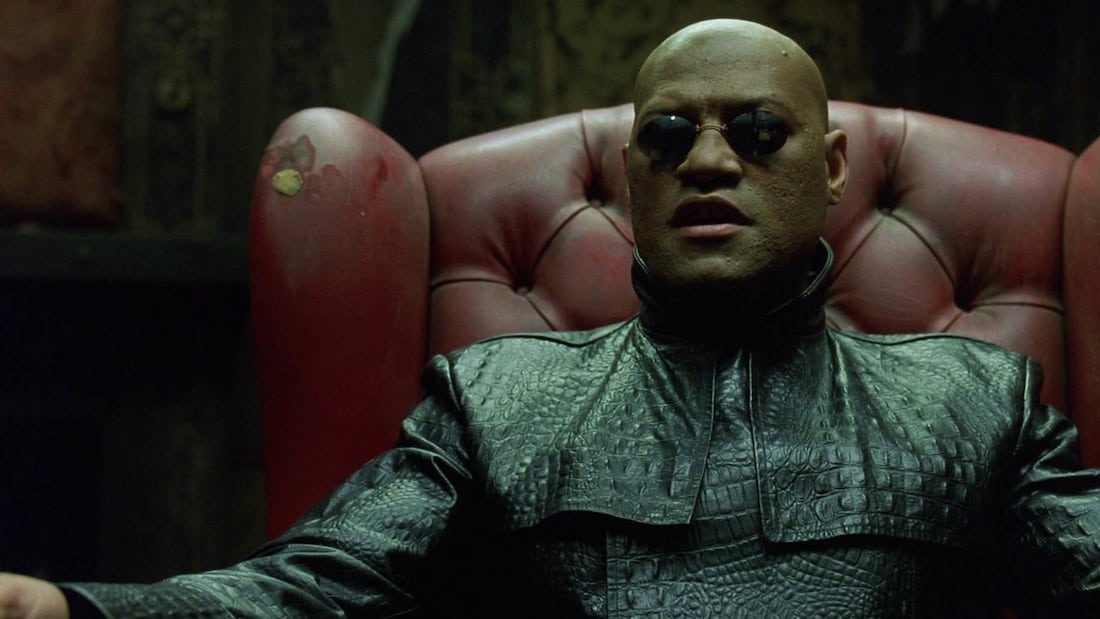

To offset the cost and perceived risk of giving them this opportunity after only one modest success, the Wachowskis tried to cast bankable movie stars Will Smith (Men in Black) and Val Kilmer (Batman Forever) as hacker Neo and his mentor Morpheus respectively. Smith infamously declined an offer to star because he couldn’t get his head around what the directors intended with the action sequences. The Wachowskis’ idea to rotate cameras 360-degrees around actors, who would thus appear to be frozen in time, sounded like madness.

This now-iconic VFX technique, dubbed “bullet time”, was still in its infancy and had only been used in a few adverts and music videos. That said, a very similar “time-slice” effect was achieved in Lost in Space (1998), but for whatever reason Smith thought the Wachowskis were insane and opted to reunite with his Men in Black director Barry Sonnenfeld for notorious flop Wild Wild West (1999). And with Smith bailing on The Matrix, Keanu Reeves (Speed) and Laurence Fishburne (Boyz n the Hood) were hired instead. Spare a thought for poor Val Kilmer, who never got a look-in once Reeves signed on because the Wachowskis wanted ethnic diversity between the two male leads.

Despite having a decent $60M budget to play with, producer Joel Silver (Predator) knew the money would go further if they shot in Australia at Sydney’s new Fox Studios. And so The Matrix became a co-production between Warner Bros. and Australian company Village Roadshow Pictures, with the cast and crew travelling Down Under for fight training and pre-production research (asked to read Simulacra and Simulation by Jean Baudrillard, together with other tomes expounding on the script’s ideas.)

The legendary Yuen Woo-ping was then hired as the project’s martial arts choreographer, partly because The Matrix would be utilising ‘wire-fu’ rigs commonly used in Asian cinema but rarely on a Hollywood movie set. The training was arduous and Reeves suffered a two-level fusion of his cervical spine which caused him some leg paralysis. He underwent surgery for the problem, which is why his character barely kicks anyone in the film.

Shooting in Sydney began in March 1998 and lasted 118 days, wrapping in August. A lot of the fights were shot last to give Reeves enough time to heal from his spinal problem, but Carrie-Anne Moss (as Trinity) filmed everything herself including the difficult wire-fu. Reeves probably had the more difficult time on the shoot, however, as he also had to lose 15 pounds and shave his entire body for the sequence when Neo awakens inside a pod covered in goo.

Inevitably, The Matrix required an extensive amount of post-production work after filming was over. Most of the technical headaches involved the aforementioned ‘bullet time’ shots, which became the film’s signature. This technique can be achieved far easier today, but in 1998 VFX supervisor John Gaeta had to mount dozens of cameras on rigs that all shot the same scene from slightly different perspectives. Computer software was then used to stitch each image together to ‘animate’ what appears to be a virtual camera movement around a slow-moving or static object.

What most people don’t notice is how the background scenery in ‘bullet time’ moments isn’t real, they’re photo-realistic CGI backdrops. Even modern audiences accustomed to false backdrops don’t spot it. That’s perhaps because it’s hard to imagine this was even possible in ’98, but it was cutting edge stuff and the final results continue to trick the eye. In fact, the most dated VFX in The Matrix is actually the simpler stuff, like a few ugly morphs whenever Agents take over the bodies of other Matrix inhabitants.

One clever but simple technique in The Matrix was to colour-code the real world (a subterranean environment below a scorched earth of thunderstorms) and the virtual world (a gleaming late-20th-century metropolis). Every scene taking place in The Matrix simulation was given a green tint by production designer Owen Paterson, with the real world always has a blue hue. These simple differences helped audiences differentiate between the two levels of reality being portrayed on-screen.

The Matrix premiered in the US on 31 March 1999. It became the fifth highest-grossing movie of the year and the highest-grossing R-rated movie. The film became a pop culture phenomenon that was endlessly parodied for years after, ending its theatrical run with $463M in the coffers. It later won four Academy Awards for ‘Best Film Editing’, ‘Best Sound’, ‘Best Sound Effects Editing’ and ‘Best Visual Effects’. That’s a remarkable feat considering ’99 saw the release of Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace, which cost $115M and was expected to clean up the technical awards that season. The Matrix was also a contributing factor in DVD becoming a success with consumers, as everyone wanted to watch it again in sharper clarity with the option to freeze and slow-mo its amazing visuals. I personally credit it with delivering such a unique viewing experience it made me upgrade to a widescreen CRT TV and invest in a Dolby Digital 5.1 home theatre system. It truly was the dawn of a new age.

But what of the movie itself? Beyond the acclaimed visuals that haven’t dated too badly, does it still have anything to offer? Of course! Some may remember The Matrix as an audio-visual experience trading in fashion and fights, but it’s heartening to remember the VFX is used sparingly and the emphasis is on story and character.

The Matrix works because it follows the hero’s journey template to the letter, with Neo discovering a hidden world and realising he’s a Messianic figure prophesied to resolve an epic battle between humans and artificial intelligence. It’s classic David and Goliath stuff, but the Wachowskis breathed fresh life into it because of their big sci-fi ideas and gorgeous detailing. The idea that we’re living inside a computer simulation wasn’t totally new, but it hadn’t been portrayed so entertainingly before The Matrix. It was more the preserve of Star Trek or The Outer Limits with their budgetary limitations.

That being said, The Thirteenth Floor (1999) was released months after The Matrix and likewise dealt with a virtual world. More interestingly, Alex Proyas’s Dark City (1998) contains clear parallels to The Matrix and was released a full year earlier. Proyas even shot his movie in the same studio as The Matrix! (Fun fact: the rooftops Trinity runs across in the opening sequence were leftover sets from Dark City that the Wachowskis repurposed!)

The key difference with those other movies and The Matrix, for audiences, is that Thirteenth Floor and Dark City were hugely influenced by film noir and harkened back to the past of the 1930s and ’40s. The Matrix had the opposite viewpoint, being distinctly modern and heralding the future in both story and envelope-pushing VFX. Its concept echoes Dark City’s idea of a world where a false reality’s been created by inhuman overlords, but it had its finger more on the pulse of modern society and culture.

In ’99, more homes were getting online with dial-up modems, and there was growing millennial tension about apocalyptic scenarios possibly coming true thanks to Y2K. The rise of A.I was also on people’s minds more than ever before thanks to computers and newfangled mobile phones growing increasingly powerful every six months. The Matrix returned to ideas that had already been popular at the cinema, like The Terminator (1984), which also involved a deadly A.I program exterminating its flesh-and-blood creators, but gave them a fresh coat of paint that made everything sexier.

The Wachowskis were also inspired by Japanese manga and anime in terms of how they shot The Matrix’s kinetic action and the oily aesthetic of their dark future. Their script also riffed on themes of identity that anime had been exploring in cyberpunk hits like Ghost in the Shell (1995). ‘Cyberpunk’ itself was a sub-genre Hollywood had dipped its toe into occasionally, but always with limited success. Blade Runner (1982) was the peak of this sub-genre, released almost 20 years before The Matrix, but even Ridley Scott’s masterpiece wasn’t a hit at the time and took years to achieve its status.

The Matrix brought cyberpunk to western live-action cinema with unparalleled success. It was a crowd-pleasing mystery-adventure and thus easier to enjoy on a superficial level for those not interested in ruminating on its deeper themes. It had likeable protagonists, a sense of humour, fascinating tech lore, a touch of romance, a stirring quest with enormous stakes, and a memorable supervillain in stoic Agent Smith (Hugo Weaving).

In revisiting The Matrix today it’s notable how ’90s it feels, particularly due to its electronic and alt-rock soundtrack with artists like Marilyn Manson, The Prodigy, Rage Against the Machine, and Rob Zombie. One of the most spine-tingling needle drops was “Spybreak!” by the Propellerheads, which plays during Neo and Trinity’s wild shootout in a lobby. The soundtrack remains great fun to listen to and is nicely complemented by Don Davis’s soaring original score, but it’s also one of the elements that give the film a millennial vibe. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, of course, but for me, it’s a weird feeling when a movie I can’t help consider modern and cutting-edge is fast becoming a historical artefact.

What worked about The Matrix still works, but so much of its story is spent answering one question: ‘what is The Matrix?’ So it’s potentially a little frustrating for those who already know thanks to pop-culture osmosis. And isn’t that everyone now? I’m not sure I knew the film was about virtual reality when I saw it in ’99, so where the story went and how it explained everything was just as intoxicating as the action sequences. It’s clearly laid out with zero fat on its bone, moving effortlessly from one amazing moment to another and always giving you the exact amount of information you need to feel eager to learn and see more. We’re with Neo every step of the way, which makes his transformation into The One all the sweeter at the end.

The only area I think might have been improved is that the undercooked romance between Neo and Trinity. When Trinity whispers her feelings to Neo to spur him back into action at the end… it works well enough, but I think more could have been done to foreshadow her feelings. And while I love Keanu in arguably his most iconic role (sorry Ted Theodore Logan and John Wick!), a part of me now wonders if The Matrix might have been even better with a black actor as Neo. It would give Neo’s story added power if he wasn’t a white man because the story’s one of futuristic slavery. Having a black man achieve God-like status to break the system would’ve carried more thematic impact, no?

However, that said, Keanu’s Zen-like nature and facial similarity to anime drawings give Neo a quiet spirituality I don’t think Will Smith or any of his contemporaries would have captured. It may also have seemed weird for Smith to be fighting a bunch of people dressed like Men in Black, with one literally called ‘Smith’?

Which brings me onto my favourite performance in the film and the trilogy as a whole: Hugo Weaving as Agent Smith. He’s such a deliciously calm and cruel antagonist; both unnerving and amusing. The Australian actor (hitherto only really known for Priscilla Queen of the Desert) walks this line without lapsing into broad caricature, although he slightly falters in the sequels because he’s required to be hammier. All of the Matrix’s Agents are heightened versions of suave authoritarian men seen in espionage thrillers (well-dressed FBI agent types with a humour bypass), but Weaving is masterful in terms of his physical movements and the measured cadence of his voice. He even manages to make unwinding a tag from a file on Neo into something with underlying malice!

Smith’s an amalgam of so many types of Hollywood supervillain (the superior haughtiness of Alan Rickman in Die Hard mixed with the relentlessness of the T-1000 from Terminator 2), and it’s a joy to watch him flex his muscles. Smith even gains unexpected depth for a piece of software we assume can’t have hopes and fears, as we realise he feels similarly imprisoned by The Matrix and loses his cool at the prospect of being stuck forever as warden to what he views as stinking biological viruses.

It can be argued it was a mistake to bring Agent Smith back for The Matrix’s sequels because his purpose was served by this story and his apparent destruction… but I can’t imagine a Matrix movie without him. How could anyone have topped what Weaving did here? It’s perfection. They just had to get him back and make him their Darth Vader figure to Neo’s Luke Skywalker.

The Matrix stands apart as the defining sci-fi action movie of the 1990s (as late as it came) and the opening salvo of a new wave of digital cinema that pushed technology and challenged the average filmgoer’s mind. We’ve grown comfortable with its ideas and have seen grander visions brought to life at the cinema since, but so many building blocks of 21st-century filmmaking were laid here. And even if the VFX and fight choreography seems relatively tame today, the drum-tight script and the way it constantly escalates the drama and fleshes out its two symbiotic worlds remains exemplary.

writers & directors: The Wachowskis.

starring: Keanu Reeves, Laurence Fishburne, Carrie-Anne Moss, Hugo Weaving & Joe Pantoliano.