VERSUS (2000)

There are 666 portals that connect this world to the other side, concealed from humanity. Somewhere in Japan exists the 444th portal... the Forest of Resurrection.

There are 666 portals that connect this world to the other side, concealed from humanity. Somewhere in Japan exists the 444th portal... the Forest of Resurrection.

If you want to see a visceral action film with zombies, gangsters, samurai swords, huge guns, and plenty of gore, then Versus will not disappoint. Throw in a good-looking young cast, who are obviously having a blast, plus an audacious debuting director with boundless energy, and what more could you want? Well, how about some mythic fantasy, a time-spanning romance, and even a twist of surprise sci-fi! Too much? Maybe! But sometimes too much still isn’t enough…

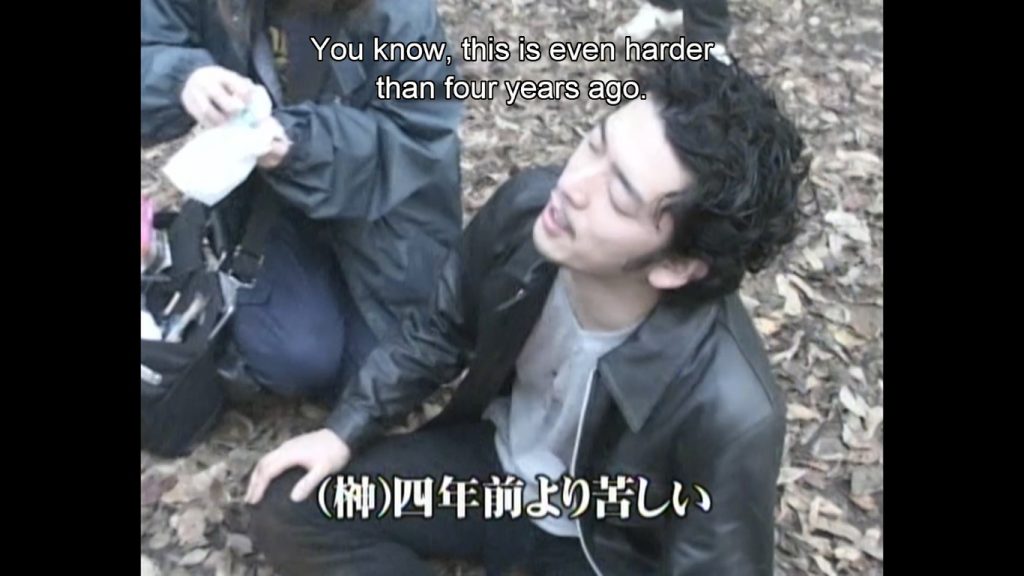

… which is why director Ryûhei Kitamura returned to the project, uniting the cast and crew four years after shooting had wrapped, to add even more cool fight choreography and iron-out a few things that had been niggling him. He added more mechanical and make-up effects, trimmed and tidied existing action scenes, and some underused characters were given a little extra screen time to strengthen their arcs. All-new spectacular fight scenes were shot with added zombies too! Both versions have now been treated to beautiful 2K restoration using the original film elements, under Kitamura’s supervision, and released in a definitive double disc Blu-ray by the ever-reliable Arrow Video.

So much relentless action runs the risk of becoming repetitive, but Versus serves it all up with such panache and a varied palette. It’s a veritable arsenal of weapons and showcase of fighting styles: armed and unarmed, realistic and fantastical. Kitamura crams in so many homages to the martial arts genre that it constitutes an almost definitive exhibition of cliches. And I mean that as a good thing! It’s cheesy and proud of it. After all, it’s the cheeseboard that leaves you satisfied after a good meal and, in terms of pure exuberant entertainment, I can think of no action-horror film more satisfying than Versus.

It’ll bring smiles to the faces of chanbara fans (especially those familiar with the classics from the 1960s and 1970s), but will also appeal to viewers coming to it from the Asia-Extreme angle—a sub-genre that it helped to kick-start when it premiered alongside Kinji Fukasaku’s Battle Royale (2000) at the Tokyo International (Fantastic) Film Festival.

The film opens with an explanation that there are 666 concealed portals to hell and number 444 is located in a remote part Japan; specifically a place known as the Forest of Resurrection. We’re straight in with Shogun Assassin (1980)-level samurai action—meeting the first character, a samurai warrior (Toshiro Kamiaka), as his sword splits an opponent down the middle, with the two halves of the body falling away to reveal him through a curtain of arterial spray. In just the first four minutes the body count is hard to tally in a furious fight between a single hero and many adversaries, with a sorcerer (Hideo Sakaki) standing stoic in the centre of it all. The conflict doesn’t play-out predictably and, if the level of violence hasn’t repelled the viewer, then they’re hooked by enough clues and unanswered questions to last the two-hours that follow.

We started in medieval Japan and Ryûhei Kitamura, with his regular collaborator and cinematographer, Takumi Furuya, conscientiously mimic the film grain and warm colour temperature to subliminally evoke nostalgia for classic samurai films—like Kenji Misumi’s Zatoichi and Lone Wolf film series of the ’60s and ’70s, to Akira Kurosawa’s more arthouse-acceptable classics like Kagemusha (1980) and Ran (1985). So, the sudden cut to a couple of escaped ‘present-day’ convicts tumbling through the forest is a jolt. And how do we know they’re escaped convicts? Their grey coveralls have ‘lawbreaker’ emblazoned down the front. Oh, and one of them still wears handcuffs, the severed hand of his captor still attached!

These are prisoners POCH-182 (Motonari Komiya) and KSC2-303 (Tak Sakaguchi), who only the most observant would’ve glimpsed, for the briefest of moments in the opening flashback. None of the characters in Versus are given names; mainly because there would be little natural opportunity for them to introduce each other, and partly because Kitamura believed that names would ground it too much in the real and tether it to a particular period. Also, some of the characters appear in different threads as effectively the same person but in different lives.

Confused? You will be! Kitamura, alongside co-writer Yudai Yamaguchi, use ingenious circular narratives to tell a generational tale of reincarnation that weaves the lives of the characters together across the centuries. Sometimes in ways that even they don’t fully understand. At times this can seem enigmatic but, rest assured, it does all fall nicely into place, piece by piece.

It certainly gives the audience credit for being clever enough to make sense of several events retrospectively. The actions of some characters can seem incongruous, unconvincing even, until a morsel of information is later revealed that puts a new spin on things. It’s a post-modern approach often cited as being pioneered by Quentin Tarantino in Pulp Fiction (1994).

So, the two prisoners soon run into a gang of coolly suited yakuza who’ve just arrived as part of their prearranged escape plan. This bunch of young hoodlums, armed to the teeth and ready for gang warfare, are as much in the dark as we are. They’re under strict orders to wait until their mysterious boss joins them and not to kill anyone until he does. They also don’t know why they were instructed to kidnap a seemingly innocent girl (Chieko Misaka) and drag her along with them. See what I mean by ‘enigmatic’?

The gangsters of Versus—more will show up later—are an inspired array of crazy characters with Kenji Matsuda stealing the show with his exuberantly psychopathic, knife-wielding fashion fop who tries to stage his own minor rebellion against the gang leader. Did anyone say overacting? Not me, his almost cartoonish, Jim Carrey-esque physical performance is a work of genius and perhaps drawing upon Japan’s Noh theatre heritage. That said, all the cast do an amazing job with juggling the furious action, self-conscious style, and comedic elements of their roles.

The underlying story is a serious work of fantasy and some of the characters have a deep emotional core. But the near non-stop action is kept light so that, whilst it’s literally gut-wrenching, its adherence to a video game aesthetic never lets one take it too seriously. Think of Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead (1981), which was a huge influence and the reason why Kitamura splashed out a good chunk of the film’s meagre budget on a Steadicam crew, just for one day, so he could emulate Raimi’s distinctive camera rush through a forest. Which brings us nicely to the supernatural, ‘zombie’ element.

When tensions run high and one of the yakuza thugs is killed, he wastes little time in rising from the dead. They’re quick on the uptake and figure out why the place is called the Forest of Resurrection. Testing the hypothesis, the knife-favouring upstart gangster kills another ‘colleague’ with the same outcome.

Turns out that the location is like the gang’s ‘Millers Crossing’ and for many years they’ve been taking their victims there for execution and burial. Uh-oh, for them and oh, yeah, for the audience—who can now sit back and enjoy guilt-free as the undead seek vengeance and get dispatched in increasingly inventive ways.

We won’t question where all the extra guns come from and how there seems to be an infinite supply of ammunition. It’s that video game aesthetic again and the film is self-aware enough to exploit this for laughs, with the smallest gangster in his skinny jeans producing a never ending series of guns from his waistband that just keep getting bigger and bigger!

Versus would make a great text for Media Studies as it joyously revels in recognisable genre tropes whilst cleverly subverting them or simply sending them up to add some light relief. The essential media theorist, Gustav Freytag, came up with a dramatic structure known as Freytag’s Pyramid where a narrative is broken down into key points that begin with an inciting incident that sets off the action, which experiences a complication before reaching a climax, unravelling toward its denouement and a final reveal.

There are times in Versus where characters briefly challenge the fourth wall by directly addressing the camera and, at one key point, when the mysterious ‘boss’ shows up, a character tells us he’s there to ‘complicate’ things. In this respect, it really reminded me of Shaun of the Dead (2004)—which I have actually used as a Media Studies exam text!

If you want to get intellectual, there’s some subtext, too, contrasting traditional Japanese values, driven by honour codes, with more modern economic motivations. We even touch upon comparative spiritual beliefs and differing ideas of reincarnation versus resurrection.

Perhaps the most surprising thing about Versus is that the characters manage to assert themselves as more than mere ciphers. There are genuinely touching moments between the girl and prisoner KSC2-303 and moments of true character reversal that can deliver an emotional sucker-punch. The ‘comic-book’ villain is anything but, and the hero reveals unexpected facets of character.

There are times when we get exactly what we expect and love it—just like when a classic metal track delivers the satisfying power riffs and histrionic guitar solo. Other moments we don’t see coming. Unless, of course you’re a confirmed fan, in which case you’ve seen it coming innumerable times. Versus is a film that bears watching and rewatching. Over and over. Apparently, it’s a popular one among fans for drinking games—but I don’t know how any of the audience would still be conscious by the finale!

Versus opened a new market for independent Asian cinema, and although domestic audiences in Japan were reluctant to embrace it, it made a name for director Ryûhei Kitamura overseas and he was able to pursue a steady, though fairly low-key Hollywood career. He’s tenaciously held on to his indie, almost guerrilla, roots even when he was accepted into Japan’s mainstream. Toho Studios recognised his prowess with the beautiful jidaigeki film, Azumi (2003), which led to him taking the helm on Godzilla: Final Wars (2004) to celebrate the iconic kaiju’s 50th anniversary.

Tak Sakaguchi became a major martial arts star, now at a level where he’s often referred to by his first name alone. He returned to work with Kitamura on his next five films, and again in Godzilla: Final Wars. His latest appearance is in the lead role as the legendary samurai Musashi Miyamoto in Crazy Samurai Musashi (2020). His fellow Versus newcomers, Hideo Sakaki and Kenji Matsuda, have also racked up impressive resumes and continue prolific careers.

Versus 2 had been planned to pick-up exactly where the first instalment leaves off. Despite being repeatedly teased by Kitamura, who says he’s had the script ready to go for more than a decade, a sequel has never materialised. He plans on making it in the US and promises it’ll be more insane! While I would definitely turn up for that, I can’t help but feel that Versus is pretty much perfect as is. I mean, the second half basically functions as a sequel to the first. Also, the little futuristic add-on to the ‘Director’s Cut’ delivers, in just a few minutes, all a sequel would really need to. The epilogue does pose a deliciously cryptic twist, one to stimulate debate beyond the end credits, and a sequel could so easily spoil its lingering piquancy… pass the cheeseboard.

JAPAN | 2000 | 119 MINUTES • 130 MINUTES (ULTIMATE CUT) | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE • ENGLISH

director: Ryûhei Kitamura.

writers: Ryuhei Kitamura & Yūdai Yamaguchi.

starring: Tak Sakaguchi, Hideo Sakaki, Chieko Misaka & Kenji Matsuda.