PHONE BOOTH (2002)

A man is trapped in a New York phone booth by a mysterious caller who seems to know his secrets...

A man is trapped in a New York phone booth by a mysterious caller who seems to know his secrets...

Close to half a billion mobile phones were being sold every year at the time of Phone Booth’s production, posing the risk that a film entirely dependent on the existence of phone booths would seem weirdly outmoded before it even began. So, in the spirit of challenging implausibility head-on, Joel Schumacher’s film starts with a montage of cell phone users (and prominent Verizon logos) while a voiceover discusses payphones, claiming that at 53rd and 8th in Manhattan stood the last old-fashioned booth of its type, due to be replaced the next day by a modern and less private kiosk.

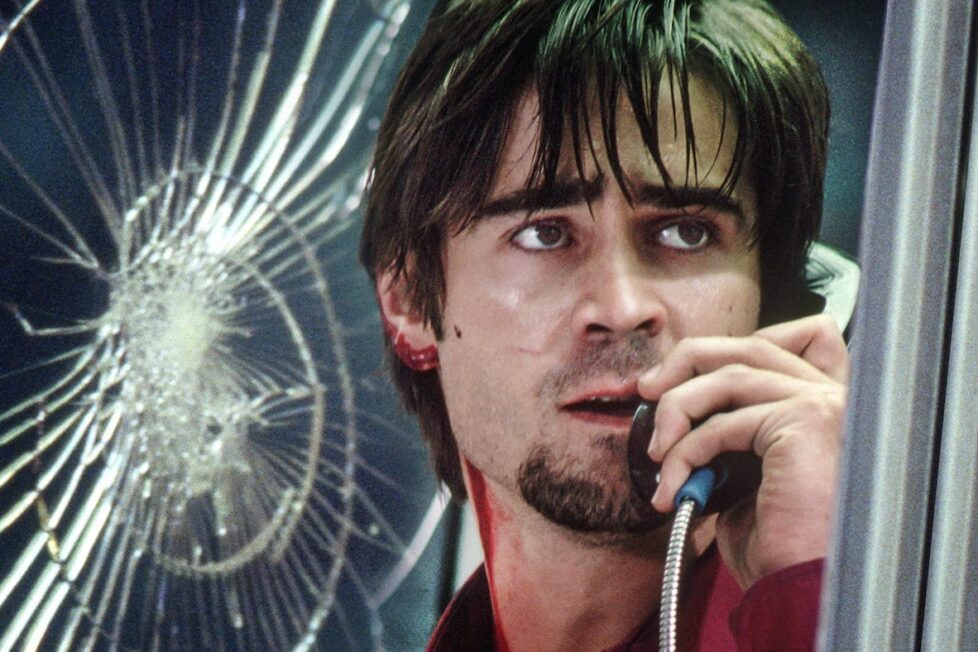

The movie makes it clear, too, that Stu (Colin Farrell), a small-time publicist and full-time sleazebag, is using a payphone rather than a mobile so calls to a young woman he plans to seduce don’t show up on the bill his wife might see, and that he uses the same phone booth for this purpose at the same time every day.

All this contrivance is necessary to support the high concept of Phone Booth and, for the most part, Schumacher’s film zips along quickly enough that we don’t really care how implausible it all is, or consider there would be much more reliable ways for Stu’s nemesis—soon to enter the story—to achieve his ends.

Before the phone booth itself appears, there’s a long sequence depicting Stu walking through Manhattan with his assistant Adam (Keith Nobbs), schmoozing on his cell, making obviously empty promises to clients. This serves to establish his character; “I’m a nice guy!” he later protests, but the film casts clear doubt on that from the beginning, and seemingly almost every writer on it compares Stu to the unethical, duplicitous press agent Sidney Falco in Sweet Smell of Success (1957).

Soon, Stu has reached the booth before a pizza delivery inexplicably arrives, then the phone rings and Stu answers it—something Phone Booth suggests few of us would be able to resist. But it proves to be a disastrous move because, at the other end, is The Caller (the distinctive voice of Kiefer Sutherland). And over the next hour or so, with events unfolding in real time, The Caller manages to embroil Stu in an ever-worsening situation that makes it impossible for him to simply hang up and leave (suffice to say that release of Phone Booth had been held over from the previous year after 10 people were killed in the Washington D.C. sniper attacks, and it eventually arrived in April 2003).

At first, Stu only has to contend with an angry prostitute who claims the booth is hers, and the street vendor who claims he’s damaged one of his toy robots (they spin around a lot but don’t get far, a bit like Stu). But by the end, he’s surrounded by police, led by Captain Ramey (Forest Whitaker), is at risk of being shot, and the ensuing stand-off is a major news story on the TV’s Stu can see in a nearby store window.

Why is The Caller targeting him? “If you have to ask, then you’re not ready to know yet,” Stu is told.

Phone Booth brought together a potentially promising mix of older and newer names. Schumacher had had some major successes in the 1980s and 1990s but had hit a rough patch after the disappointing performance of Batman & Robin (1997), with smaller-scale subsequent films like 8mm (1999) and Flawless (1999) also meeting mixed responses. Larry Cohen, the screenwriter, had been writing since the 1970s but had never been associated with a major hit, although he’d penned some interesting New York-set movies.

The onscreen talent, meanwhile, was much younger: Farrell was a noted up-and-coming actor at the time, especially following Minority Report (2002), Sutherland was enjoying a career resurgence thanks to 24 (which had just started on TV), and Whitaker was a respected performer mostly in character parts, though he’d also been acclaimed for his lead role in Jim Jarmusch’s Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (1999).

Of these three main performers, Farrell is the one from whom the film’s attention rarely strays and he delivers an effective, slightly comic portrayal of a man falling apart… but it’s Sutherland’s Caller (who barely appears on screen and describes himself as “no-one you’d ever notice”) who gets all the best lines and largely drives the story. Whitaker is his usual likeable, slightly hangdog character; Radha Mitchell (Pitch Black) is narratively important as Stu’s wife but given no chance to do anything with the part; and among several entertaining cast members in much more minor roles, Josh Pais is one who stands out as Mario, a dissatisfied restaurateur client of Stu.

Stu apart, though, it’s not really a people movie at all despite the high dialogue-to-action ratio; it’s Schumacher’s direction, along with photography by Matthew Libatique and editing by Mark Stevens, that give Phone Booth most of its character. It’s visually hyperactive from the opening (hurtling from a communications satellite in space down to Earth, and then into the circuitry of a telephone system), and although it was actually shot in Los Angeles, Schumacher takes every possible opportunity to add visual variety to the mundane “New York” location.

There are shots from above and below; shots of buildings (especially windows) and sky; speeded-up street activity; a zooming, lurching camera to suggest Stu becoming dizzy with anxiety. Schumacher even resorts to posterisation at times and makes extensive use of split screen and picture-in-picture—to the point that whenever there are vertical lines in the background, the viewer starts wondering whether the screen is being subdivided again.

The suspenseful electronic score—credited to Harry Gregson-Williams but with much material by Nathan Larson, who was replaced on the project—is very different in style, almost unnoticeable at times and blending with the street sounds, but if anything it adds more than Schumacher’s rather overheated technique. The problem with Phone Booth’s attempts at creating visual excitement is that they can detract from Stu’s constrained situation: by showing police and TV crews that are not visible to Stu, for example, by occasionally using The Caller’s POV, and on a couple of occasions by completely cutting away to characters elsewhere.

Critics mostly weren’t impressed by such overt showmanship and felt it imperfectly concealed an unsatisfying tale. Stephen Holden in The New York Times called Phone Booth a “flashy stunt”, a “clanking, overheated thriller” and “essentially a one-act radio play”; Todd McCarthy in Variety similarly thought it thin and suggested it might have worked better as an even briefer TV production, or a short film. Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian said it was “a characteristically rackety and ridiculous picture from the irrepressible Joel Schumacher”, though he acknowledged that “it’s carried off with a certain pugnacious panache” and “like a static Speed”.

None of this deterred audiences too much, with both Farrell and the intriguing concept doubtless contributing to the movie’s commercial success; though it wasn’t high on the year’s box office scorecard, its low budget (enabled by a very short shoot) meant the profit margin was high.

Schumacher’s show-off approach isn’t a flaw of Phone Booth, exactly, though some might find it irritating and it certainly works better on the big screen than at home. Similarly, the mixed-up POV isn’t fatal, though it does undermine claims of Hitchcockian intensity. Cohen is said to have pitched a similar idea to Hitchcock decades earlier, and there are obvious affinities to both Rope and Rear Window. Nor is the time spent on Captain Ramey’s back story (enough to slow things down, not enough to become interesting) seriously damaging.

The major weakness in the movie is simply that the premise makes little sense. The Caller’s previous targets have been unquestionably bad people—including a paedophile and an executive who deliberately ripped off investors—yet Stu is nothing more than a selfish, superficial philanderer. There must be tens of thousands like him in New York, so why would The Caller pick this minor sinner in particular? His portentous judgement (“you are guilty of inhumanity to your fellow man”) is unconvincing.

Still, there’s a good late twist involving an item hidden in the phone booth, and if the ending is no great surprise, the film manages to maintain interest in exactly how it will be achieved. Phone Booth may be a movie with a fundamental narrative flaw and some questionable directorial decisions, but with its almost nonstop pace and its short duration, few viewers will be thinking about any of that until it’s over.

USA | 2002 | 81 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Joel Schumacher.

writer: Larry Cohen.

starring: Colin Farrell, Kiefer Sutherland, Forest Whitaker & Radha Mitchell.