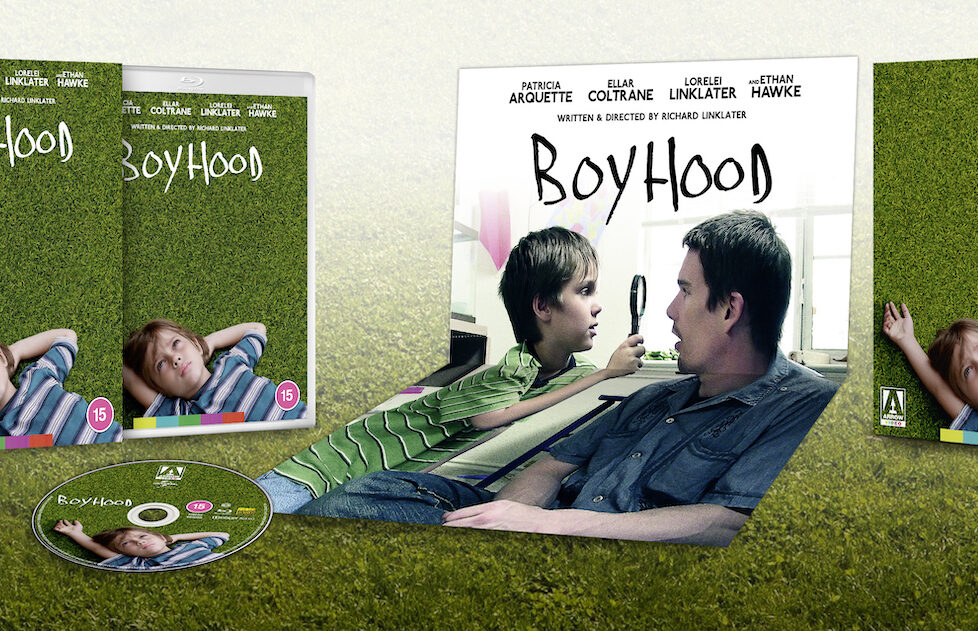

BOYHOOD (2014)

Over a dozen years, a boy matures into young adulthood as his family and the world change around him.

Over a dozen years, a boy matures into young adulthood as his family and the world change around him.

Richard Linklater’s Boyhood is surely amongst the most convincing films ever about the experience of childhood and adolescence. The key word there is “experience”. This is a movie not as much concerned with an over-arching storyline, more suggesting to us, or reminding us, what it’s like to be a boy. But it’s also a movie about adulthood, families, time, and living life; a film whose canvas seems limited but is far wider than most.

Even before it opened, the unusual scope of Linklater’s ambition was attracting attention: Boyhood filmed a few days each year over a long period, from 2002 to 2013, with the same cast growing older during its production. Its focus is on Mason (Ellar Coltrane), who’s about six when we meet him, lying on the grass gazing at the sky. He’s 18, getting high on his first day at university—and, perhaps significantly, looking at nature again—by the time the film ends.

But the other children-becoming-adults (most notably his sister, played by the writer-director’s own daughter Lorelei Linklater), as well as several characters who are adults from the beginning, are collectively as important as Mason. Despite the movie’s title, the changes (or lack of changes) in them as the years pass are often equally as striking as Mason’s.

Linklater’s unusual, if not utterly original, approach to production had a significant influence on the finished movie. He shot it all on 35mm film for consistency, realising that digital technology would likely change noticeably over the course of a dozen years; one effect of this is to make it seem a bit older than it really is (just as memories can seem more distant than they really are). Yet it never once conveys nostalgia: even the things that date specific episodes in Boyhood (the lime-green iMac, the Prisoner of Azkaban bookshop launch party) were contemporary when those scenes were shot, and though the music was mostly chosen later, it slots well into the timescale.

If there is a “story”, as such, it’s reducible to a few words: ‘Mason grows up and learns more about himself’, or maybe just ‘people change in some ways, not in others.’ Yet while Boyhood certainly isn’t built on a conventional three-act structure, it’s never lacking in incident. In fact, it moves surprisingly quickly, even if recollections of the movie afterwards may be somewhat dreamier.

Similarly, although much of its dialogue—dominated by everyday chat about doing the dishes or leaving Facebook—may give the impression of being improvised, in reality virtually none of it was. (Linklater started out at the beginning of his 12-year project with a general notion of where the movie would go, then wrote the screenplay year-by-year, partly reacting to changes in his own performer’s lives.)

So, while Boyhood is at heart a film about the way small and largely unremarkable experiences add up to a life—rather than about defining life through a few dramatic episodes, as films mostly do—it’s not just an exercise in observation of random moments. There is a point to it all, but one that’s implied rather than proclaimed; Mason says, toward the end, that speaking his feelings “never sounds right… words are stupid”, and Linklater is similarly reluctant to make meaning overt.

Given the 12-year shoot, Boyhood technically falls into a dozen chunks, but it feels continuous and doesn’t announce jumps forward in time. (Yet again, the film works like memory, which doesn’t label things with specific dates). Often, indeed, it’s only a change in the appearance of Mason—especially his hair—which signals to us that more time has passed.

It’s entirely set in Texas, largely Houston and the much smaller city of San Marcos, as Linklater himself had been born in Houston and there are several ways in which Mason’s life resembles his own, though Boyhood isn’t autobiographical.

Mason and his slightly older sister, Samantha (Lorelei Linklater), have relatively normal childhoods in which the biggest dramas are, unsurprisingly, provided by the adults. One, indeed, has already taken place before the movie begins: the split between their mother (Patricia Arquette) and their father (Ethan Hawke). The latter’s reappearance in their lives after an absence supposedly working in Alaska is the first major event in the movie.

This provokes immediate arguments between the two estranged parents, but as Boyhood progresses it’s Mason’s separate relationships with each of them that assume more importance than the relationship between them, which we see only obliquely—as, indeed, a child would.

Mom also splits up soon with her latest boyfriend (Steven Chester Prince)—a change in life which, like many in Boyhood, isn’t shown explicitly but simply left to us to deduce. She then enters into another relationship, this time with her college teacher Bill (Marco Perella), and this leads to the section of Boyhood that most closely resembles a more conventional “issue” drama.

Bill turns out to be a demanding, even dictatorial man (he forces Mason to have a haircut that makes the young boy look like a recruit from Full Metal Jacket; when he tells Mason’s mother on another occasion that “you have to draw a line”, she pointedly observes “you have so many lines, Bill.”) He also, more nastily, turns out to be a mean drunk.

Bill is eventually replaced in the life of Mason’s mother by Jim (Brad Hawkins), but there are signs he may be heading the same way as Bill; the audience realises long before the still immature Mason that his mum has a seemingly self-destructive taste in men. She teaches her own students that “human survival depends on us falling in love”, but she may be deluding herself.

“Take care of your dad now, son, you’ve only got the one,” a liquor store owner tells the multi-fathered Mason in one of the movie’s few moments of knowingness. But understanding difficulties in your parents’ relationships is a very adult kind of perception and Mason is not there yet.

He’s busy first with childish things (collecting arrowheads and snake vertebrae, ogling lingerie catalogues with his pals, speculating about possible Star Wars instalments with his dad around the campfire). and then with more teenage things. The lingerie catalogues are replaced by online pornography, he becomes interested in photography, he becomes sceptical about digital media, he becomes interested in actual girls; this young man from a decidedly liberal, Obama-supporting family is even discreet enough to be polite when a well-meaning elderly couple give him a Bible and a gun for his 15th birthday.

A lot happens in Boyhood, then, and even if not an awful lot “happens”, in the sense of traditional narrative-led movies, it’s compelling stuff. That’s the difference between real life and fiction, perhaps: hardly any of us actually take part in bank robberies, hostage rescues or dinosaur-fighting day to day, but few of us find our lives unbearably boring as a result. The small stuff, experienced rather than just described in a detached way, can be equally absorbing and Boyhood gets as close as any non-documentary film ever has to real life.

In Linklater’s movie, then, a great deal rests on the cast—given that what happens is (for the most part) not very different from anyone’s life experiences, it’s up to the actors to convince us that these small events really do matter. And they are, without exception, outstanding.

Coltrane is the face of the movie, literally: that shot at the beginning of the small boy lying on the grass and contemplating the unknowable skies was featured on the poster, and virtually every article on the film uses at least one still of the young Coltrane. His performance throughout the 12 years is compelling, aided by his expressive face; we can tell that Mason has strong opinions even though he’s not always assertive about them.

The natural process of physical and emotional maturation helps too, of course; like any young person, he changes in unexpected ways as well as predictable ones, giving a sense of realistic development to the character. In his teens, he’s more amused by the world, even cynical, than he was before, but still retains that sense of wonder.

Lorelei Linklater is his equal as Mason’s sister, albeit in a slightly smaller role, and the contrasts between her and her brother are telling: when they are both young she cares much more than he does about feigning maturity, and she’s far more aware than he of the effect she has on others, for example with her sarcasm. As they grow older, however, the gap closes.

Both Coltrane and Lorelei Linklater went on to modest acting careers. Arquette and Hawke, however, were already established names when production of Boyhood began (and she won its only Academy Award, although Hawke, Richard Linklater, editor Sandra Adair, and the movie itself were also nominated).

It’s Arquette, as the mother, who has the closest thing in Boyhood to a big emotional scene, momentarily upset by the rapid passing of her life: “I just… thought there would be more.” Earlier she has observed that she herself went straight from daughterhood to motherhood, with none of the extended in-between that modern western society valorizes (and which Mason’s father has apparently tried to stretch out as long as possible in his own life).

But even if Arquette’s outburst is slightly out of keeping with the rest of the movie, this scene jars only slightly—people do have emotional moments, after all—and for most of the film, adult disappointment in the way life turns out is only hinted at, perhaps barely grasped by Mason. And Arquette’s character comes across as completely real, able to move from serious reflection to jokiness in an instant. This obviously intelligent and perceptive woman’s repeated mistakes in relationships only add to the character’s interest; it’s difficult to understand, but then people often are.

Hawke, as Mason’s natural father, at first looks like an easier person to read: something of a slacker, more interested in having fun than in parental responsibility. But either that’s an act in itself, or he changes because, as the years pass, it becomes clear that he is, if anything, more of a conventionally concerned parent than Mason’s mother. He even seems quite content in his insurance career, though he still likes to talk about his earlier life as a (possibly self-styled) musician.

In smaller roles—none of which extend throughout the film’s duration the way that the core quartet of Mason, his sister, his mother and his dad do—Perella is disturbingly nasty as the professor-turned-domestic-abuser, even if the role is slightly stereotyped; Hawkins is more quietly chilling as the younger army vet and prison officer who becomes the next partner of Mason’s mother, and whose own potential capacity for violent outbursts remains worrying.

Seen much more briefly than these two, but intriguing as their potential successor, is Mason’s boss (Richard Robichaux) at a restaurant where he has a part-time job; this man turns up to the boy’s high-school graduation party and though the camera doesn’t foreground him, we can’t help but notice how much interest he’s showing in Mason’s mother.

Other stand-outs in a movie where the majority of characters don’t even have names and appear only for single scenes include Zoe Graham as Sheena, for a while Mason’s girlfriend; Bill Wise as his embarrassing uncle Steve; Richard Andrew Jones as the elderly man who gives Mason the gun; and Roland Ruiz as another very different young man, first encountered as a low-paid labourer working on the family’s house but later getting an education after encouragement from Mason’s mother.

All these performers add a great deal to the movie’s texture… but, of course, it’s Mason and his immediate family who dominate. It’s their slow transformations which illustrate the passage of time, aided by Linklater’s consistently inobtrusive filmmaking technique, and which allow Boyhood to deal equally effectively with two rather different things: a single boy, and the world around him.

Mason’s own emerging identity is key, of course, but so is the way that the activities of adults provide a structure to his life (Boyhood at times recalls Noah Baumbach’s Marriage Story in its dealings with grown-ups).

So, too, are the more transient roles played by the other children he knows, and so are the settings of childhood’s different stages, both literal and emotional. Boyhood sets up an interesting quiet tension between Mason’s existence as part of society and his self-containedness as an individual; though there are always other people in the movie, many of them simply disappear, and though he is a sociable enough being it’s hard to escape the implication that he—and all of us—are ultimately alone.

Before the release of Boyhood, a small handful of other film-makers had used a similar ultra-time-lapse approach to telling a story stretching over a long period, most famously the British director Michael Apted, who in his Up series of TV documentaries revisited the same individuals every seven years from 1964 to 2019. Another Brit, Michael Winterbottom, filmed Everyday (2012) over five years.

It was Linklater and Boyhood, though, who introduced the concept to many viewers. Even so, while the innovation is noteworthy, the movie’s real greatness lies not in this but in its impact.

Boyhood is, undoubtedly, one of the finest films ever made about childhood, worthy of ranking with work like Satyajit Ray’s Apu trilogy (1951-59), Truffaut’s Small Change / L’Argent de Poche (1976), and more recently Eskil Vogt’s The Innocents (2021), as well as the oeuvre of Spielberg. There’s no shortage of strong movies about the teenage years and young adulthood—among them Linklater’s own Dazed and Confused (1993), Larry Clark’s Kids (1995) and Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show (1971)—but there are many fewer that manage to evoke the preteen years so well, and if that was all it did Boyhood would still be a masterpiece.

Yet it does more, too. Its other subjects are hugely ambitious for a movie that feels so low-key from moment to moment: the nature of time, memory, and living.

Boyhood happily mixes up the mundane with the meaningful, exactly as we all do every day. It doesn’t allocate screen time rigorously according to the significance of events, because that’s not how we experience or remember them. The trivial can often seem important, and can often be recalled in detail after the significant is forgotten.

It depicts change, quite big changes, but it doesn’t draw sharp distinctions between one phase of life and another, because they aren’t really there; existence as we experience it is linear. “It’s always right now,” Mason says in almost the last line of the film.

And, just maybe, being right now is all there is. “What’s the point?” Mason asks his dad earlier on. Hawke’s character replies that he doesn’t know; “we’re all just winging it”.

But that’s not an admission of failure, or futility, at all… because what Boyhood demonstrates again and again is how much the smallest things, the fleeting ones, can be real sources of delight in movies, just as they are in life.

USA | 2014 | 165 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

writer & director: Richard Linklater.

starring: Ellar Coltrane, Patricia Arquette, Ethan Hawke & Lorelei Linklater.