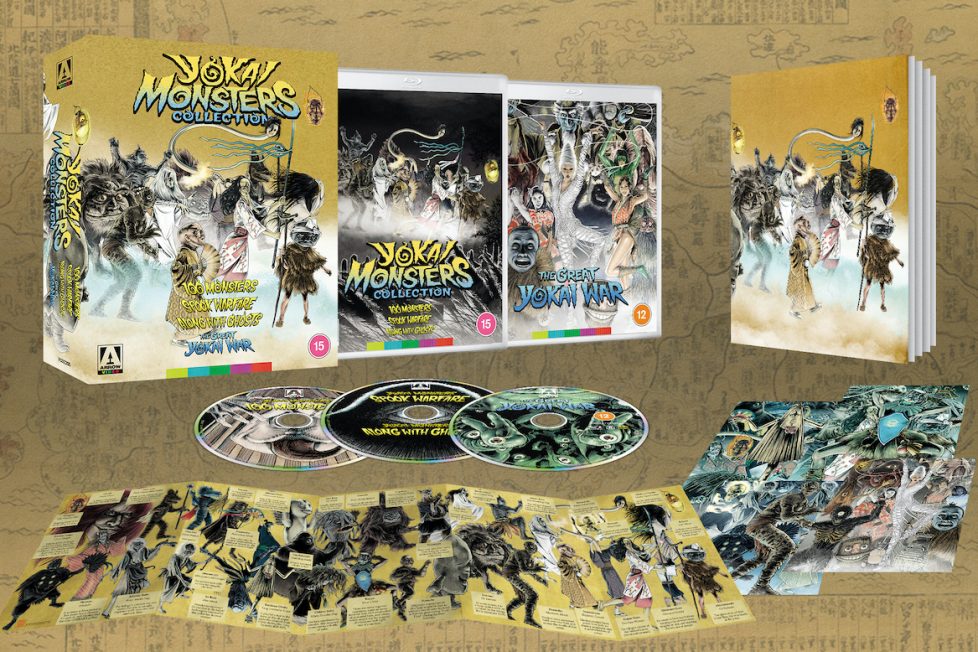

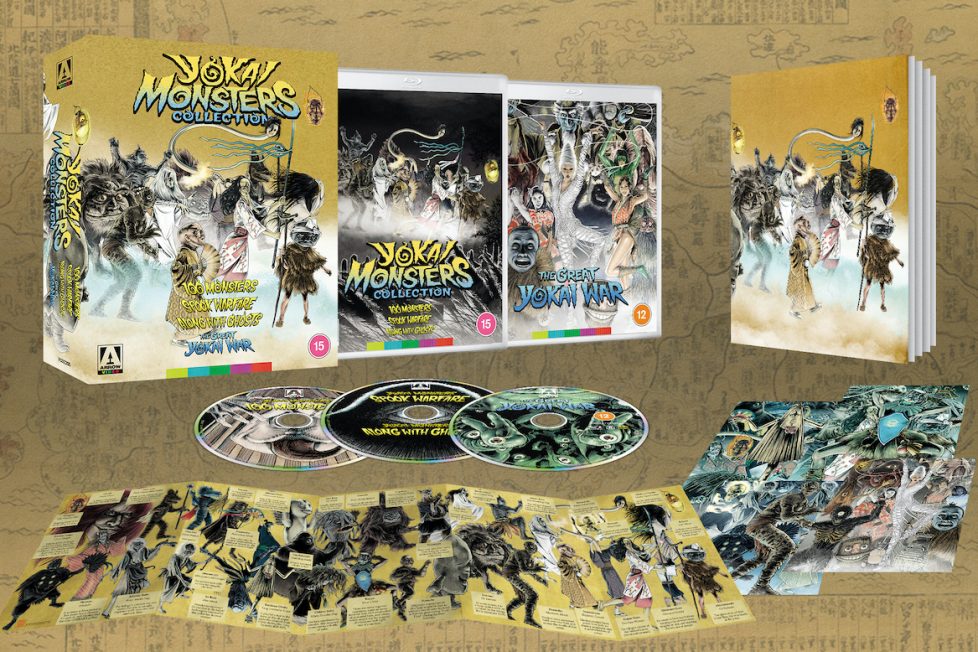

Yōkai Monsters Collection (1968-2005)

A review of Arrow Video's Blu-ray box-set 'Yōkai Monsters' Collection, featuring 100 Monsters, Spook Warfare, Along with Ghosts, and The Great Yōkai War.

A review of Arrow Video's Blu-ray box-set 'Yōkai Monsters' Collection, featuring 100 Monsters, Spook Warfare, Along with Ghosts, and The Great Yōkai War.

This attractive box set from Arrow Video should please anyone with an interest in folklore, fantasy, ghost stories, fairy tales, and weird world cinema. Gathered here are Daiei’s Yōkai Trilogy, consisting of 100 Monsters (1968), Spook Warfare (1968) and Along with Ghosts (1969), all made back-to-back and directed by Kimiyoshi Yasuda. The fourth film, Takashi Miike’s The Great Yōkai War (2005), is an audacious reboot rather than a remake. If you already know what yōkai are, you’ve probably already placed a pre-order!

Likewise, if you’re familiar with Daiei’s output, you’ll find these of interest, as the Daiei Studios were one of the two major studios in post-war Japan, making an international impact with Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950) and dominating the chanbara genre with the immensely popular Zatoichi series of films featuring the blind swordsman. They also gave rivals Toho a run for their money with their answer to Godzilla, the flying rocket-powered turtle kaiju Gamera. However, by the late-1960s, both the Zatoichi and Gamera franchises were losing their box-office draw and the studios were casting around for another suitable genre to exploit. Luckily for us, they settled on yōkai, but it wasn’t enough. A few years later, in 1971, the old studios were declared bankrupt and remained dormant for a few years before being slowly revived with fresh investment.

Knowing what yōkai are doesn’t necessarily mean one can give a simple definition. The concept is analogous to that of the Manitou of America’s First Nation people— an animistic belief that everything is imbued with a spiritual aspect. Even inanimate objects and places will accrue their own Manitou, given time. Likewise, yōkai are often associated with specific sites and even old household utensils can become yōkai after a century of use. How they have been used and cared for will affect their personality.

Animals can become yōkai when they reach a certain age. Some yōkai are terrifying, some are quite funny, others are just plain weird. Each has its own personality and, in general, will do no harm if treated well or appropriately appeased. A few are ambiguous, and some will definitely eat you, given half a chance. They’re akin to the European idea of fairies which varies regionally and includes scary beings like goblins and ogres, as well as benign sprites and dryads…

Yōkai are often lumped in with Oni, which are more like the western idea of demons; yūrei, which are ghosts, lost souls, and vengeful spirits; and kami which are also difficult to define with Western terminology and can be deities to begin with, or an outstanding human can become a kami—like being recognised as a genius, which originally meant attaining one’s higher spiritual state. It may even be possible for a yōkai to become a kami and vice versa. So, there’s plenty of overlap.

They’ve always been there in Asian folklore, but became a widely popular subject for Japanese storytellers of the Edo period when they were categorised by the artist and scholar, Toriyama Sekien, in his illustrated Yōkai Dictionaries. It became a fashionable pastime to gather and tell spooky stories about yūrei and yōkai.

So-called ‘gatherings of 100 supernatural tales’ / hyakumonogatari kaidankai involved lighting 100 candles, and each guest took turns to recount a tale. When their story was told, they would snuff a candle until just one was left burning. Now, when that final flame was extinguished, a spirit from one of the tales would appear! Usually, that last candle was left burning and the guests made their excuses, leaving the host to recite a cleansing prayer before it went out. Sometimes, if the party was feeling brave, having perhaps fortified themselves with enough sake, they would blow out the last candle and see if anything manifested. I know what we’ll be doing this Halloween!

Picture scrolls depicting the many and varied yōkai circulated throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but it was prolific manga artist Mizuki Shigeru who brought them back into contemporary Japanese culture. His illustrated stories redefined them as mischievous spirits with playful characters that would only appear to children and those with peace in their hearts. His yōkai comic-books inspired a generation and were hugely popular in the 1960s creating the audience for Daiei’s Yōkai Trilogy. Many of his characters were later reinterpreted as Pokémon and went on to directly inspire The Great Yōkai War in which, at the age of 83, he makes a cameo as the ‘god of yōkai’ proclaiming his pacifist message, “wars only make you go hungry.”

The local yôkai (Japanese spirits) interfere to avenge a murder and thwart the plans of corrupt officials.

The Japanese title, Yōkai Hyaku Monogatari, translates as 100 Yōkai Stories. So, here the translator has settled on ‘monsters’ as a generic term for such supernatural beings. I suppose that fits well as westerners know what a ‘monster movie’ is, and it’s a category all these films could fairly comfortably sit in. We start with an ending as a lone traveller is seemingly hugged to death by a massive cyclopean Tsuchi-Korobi, which resembles a hairy mound of earth. This is a vignette from a ‘gathering of 100 supernatural tales’ and it seems the man (Shôzô Hayashiya) survived to tell the tale to his audience of modest means who hurriedly perform a protection ritual after the last candle burns out. Starting with a story within a story leads us into the world of the yōkai, and suggests how we approach the ensuing narrative. Is it simply the next tale to be told? Of course, for the viewer to think that they’d need to be aware of the tradition.

This first film in the trilogy is riffing on formats already well established by Japanese period dramas known as jidaigeki and assumes quite a bit of prior knowledge. So, western audiences may find it hard to follow. In one key part of the story, the same character is actually in two places, wearing different clothes, at the same time, which is difficult to get one’s head around and, if you don’t, the ending won’t make much sense.

The main arc follows a popular jidaigeki trope of peasant villagers rising up against an evil landlord, often with the assistance of a masterless samurai known as a Ronin, who the lord’s men don’t count on. Two rather good examples would be Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961), and Hideo Gosha’s Three Outlaw Samurai (1964)—as both films share many of the same ingredients, but 100 Monsters breaks with convention by throwing in a huge helping of supernatural elements.

The provincial lord Hotta-Buzennokami (Ryûtarô Gomi) has foreclosed early on a loan so his business partner, Tajimaya (Takashi Kanda) can ‘legally’ evict the tenants of a boarding house and demolish its shrine to an all but forgotten minor spirit. When Tajimaya’s men arrive to serve notice, the old caretaker and umbrella maker, Gohei (Jun Hamamura) stands up for the peasants but is beaten so severely he later dies. However, when Jinbei (Tatsuo Hanabu) the owner of the tenement house does come up with enough money to pay off the debt, he too is killed and the money stolen. Luckily one of the residents Yasutaro (Jun Fujimaki) appears to be an ex-samurai and, though initially reluctant to intervene, decides to stand up to the lord’s thugs.

It’s a pretty straightforward costume drama until the storyteller arrives to entertain a gathering at the lord’s house. Here we’re treated to another supernatural tale, making the film a kind of horror portmanteau. This time the story features Rokurokubi, a popular yōkai that usually takes the form of a beautiful woman. However, when the woman falls asleep, her head roams the surroundings on the end of an infinitely extendable neck to feed on small animals and drink lamp oil, apparently.

This time, though, when it comes to the last candle, the host implies that performing the cleansing prayer would be an admission of weakness and belief in old-fashioned superstition. Keen to appear both powerful and modern, the lord declines to perform the ritual and instead indulges in a show of wealth by handing out boxes of money to his attendant cronies. It’s a heavy-handed metaphor of how capitalism was seen to be eroding the traditional culture of Japan, drawing a comparison between the decadence of the late Edo era and post-war consumerism.

We’re about mid-way through when the fun really begins. The first yōkai to manifest in the ‘real’ world story that frames the nested narratives is, perhaps fittingly, Karakasa Kozo, the totally un-scary yōkai of an umbrella. Possibly conjured from the discarded umbrellas of the murdered Gohei, it only appears to Tojimaya’s son, Shinkichi (Rookie Shin-ichi) who’s never grown up and retains the innocence of a child. So, the Yōkai does him no harm and instead licks him playfully. Yōkai go in for a lot of licking in these films!

Of course, more yōkai appear in the final act and help to protect the peasants, their shrine, and serve justice. The look of the yōkai is based on original picture scrolls with the addition of some as they appear in Mizuki Shigeru’s manga illustrations. They’re clearly actors in costumes and masks, echoing the theatrical traditions of Japan. There are some weird effects sequences of doors seemingly opening and closing on their own because the yōkai reveal themselves only to their victims and generally, they don’t actually kill anyone. Instead, they cause confusion so people attack what they think is a demon, only to find it’s one of their colleagues.

JAPAN | 1968 | 70 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

When a Babylonian vampire comes to old Japan, an army of Japanese demons and ghosts gather and battle him.

This is the most westernised ‘monster movie’ in the collection with some elements that wouldn’t seem at all out of place in Hammer horrors. Perhaps Spook Warfare was made with an eye on the international market. Its Japanese title Yōkai Daisensō translates as The Great Yōkai War and suitably, the yōkai are brought more to the fore to become principal players. It also feels a little like an extended episode of Monkey (1978-1980).

The film opens with a great sequence among the ruins of a Babylonian city. It’s a beautifully rendered combination of miniature effects and live-action as tomb robbers break into a sealed chamber and retrieve what looks like a golden staff. The disturbance awakens the spirit of an ancient and decidedly malevolent demon. Taking flight across the ocean, its giant wings whip up a devastating storm, sinking sailing ships in its wake…

Samurai lord Hyogo Isobe (Takashi Kanda) and his daughter Chie (Akane Kawasaki) are fishing by lamplight when they see the storm approaching. Isobe is the first victim of the Babylonian demon who drinks his blood and then possesses him, instantly infiltrating the household. However, the demon cannot stand the shrines and destroys them in a frenzy, throwing objects and votive offerings out. He flings an item far enough to land in the decorative pond outside, which just happens to be where Kappa (Gen Kuroki) resides, and emerges to see what all the commotion is and, of course, can see the demon for what he is.

The Kappa is a mischievous water spirit resembling an anthropomorphised frog-turtle hybrid. They’re popular yōkai appearing in many stories where they can also be dangerous, pulling fishermen to their watery doom and sexually assaulting women who come to wash at the riverside. Here though, we have one of the brash, fun-loving examples of its race who’s really the star of the show. So, if you find him too irritating, that’ll become a major distraction from the action.

Kappa confronts the demon and is surprised when he’s bested by this foreigner in a semi-slapstick fight sequence. He flees into the woods where he gathers a few fellow yōkai and explains the situation. Yōkai are protectors of the land and know they must rise to challenge this invader that threatens to destroy their shrines and the traditional way of life. Again, a blatant metaphor condemning foreign influences that threatened post-war Japanese culture, still trying to redefine itself. Here, Tetsuro Yoshida, who scripted all three of the Daiei Trilogy, draws from traditional tales of native spirits and animals defending their islands against demons and also takes much from the storyline of Mizuki’s GeGeGe no Kitarō manga series that was popular at the time.

I was pleased to see my favourite yōkai, the Tanuki, become a major player. In Japanese folklore, the Tanuki, which is really a type of wild dog, is a powerfully magical animal that can shapeshift. It can therefore disguise itself as pretty much anything you can think of—the moon, a teapot, on occasion a train! It also has the ability to enlarge its testicles and use them as flotation aids to rescue drowning people or to ferry its friends across lakes and rivers. It doesn’t display that talent here but can inflate his belly and become a sort of television set for remote viewing—I don’t think that’s a traditional attribute.

As word spread, the number of yōkai coming to aid the Kappa grows. Karakasa kozō, the umbrella we met in the first film joins the gang—not sure what good it’ll be against a blood-sucking, storm-bringing, size-changing, towering demon but, you’d be surprised! At the heart of all these yōkai films is a theme of the small and seemingly less significant playing an essential part. Which is a positive message for the kids in the audience.

The other major player is Futakuchi-onna (Keiko Yukitomo), a woman with two faces; one is young and pretty where you’d expect the face to be, and the other is on the back of her head that’s usually just a big set of jaws. Here she has the freaky addition of an extra-long nose with a tiny hand on its end! Her ability to rotate her head to switch between her two looks is used to comic effect a couple of times. She also has the ability to create illusions of people who are no longer in the room.

For the time, the SFX would’ve been impressive, though the man-in-a-suit demon looks rather quaint nowadays. For the most part, the yōkai costumes and prosthetics hold up on camera, until they speak, and their lips don’t move. They would’ve compared favourably to contemporary movie monsters and, as with Hammer films and Doctor Who, the artifice demands an element of audience participation. When the viewer invests their imagination, they’re drawn deeper into the world of the story for as long as it remains consistent.

JAPAN | 1968 | 79 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

The murder of an old man on sacred grounds provokes the intervention of vengeful yôkai.

The final instalment of the Deiai Trilogy is, for me, the most solid and successful. The yōkai are used more sparingly than in Spook Warfare and more subtly than 100 Monsters, but still drive the narrative to play a decisive role. This time around they’re more yūrei than yōkai. Tetsurô Yoshida, who penned all the Daiei Trilogy. seems to have hit his stride and the storytelling is well-crafted. We’d seen what Hiroshi Imai could do in the second film but here, his cinematography is just beautiful.

As with many such samurai films, the two-way influence of the Western genre is evident throughout. I’d be surprised if Along with Ghosts hasn’t been loosely remade with a Wild West setting! Certainly, there are parallels with many, though the ghost story thread would make it unusual. Sergio Leone is known to have looked to the east for inspiration, basing A Fistful of Dollars (1964), on Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961), with his third Dollar movie The Good, The Bad and The Ugly (1866), inspired by Three Outlaw Samurai (1964). This trans-global resonance may be what makes the final instalment of the Daiei Trilogy the most accessible to a mainstream audience. Or, it may simply be the engaging human story at its heart about courage, honour, and love.

A group of samurai gathers on a lonely stretch of road, intending to ambush a traveller who carries documents that can incriminate their lord. They tell the old monk (Bokuzen Hidari) praying at a nearby shrine to leave but he argues that he hasn’t finished his prayers. He senses their ill intent and warns them that to interrupt prayer is bad enough, but to murder someone at a shrine will only bring retribution from the spirits.

When the thugs waylay their victim, the old man makes a lunge for the documents and is dealt a mortal blow. He returns to his home where he’s discovered by his little granddaughter, Miyo (Masami Burukido). Before he dies, he tells Miyo to seek her father in the town of Hamamatsu. Giving her a set of gaming dice, he explains that her true father will recognise them and know who she is.

Believing that he has passed the documents to Miyo, she’s now pursued by her grandfather’s killers. She embarks on a long and eventful journey along the haunted Tokaido Road where she is helped by a series of kindly humans and unseen mystic forces. First to come to her aid is Shinta, a young orphan boy who travels with her for part of the way. Later, the wandering Ronin, Hyakasuro (Kôjirô Hongô) takes her under his wing and becomes her surrogate father for a while. He’s a classic honourable samurai who could’ve stepped out of a Kurosawa epic.

The character interactions here are all well observed and adroitly deployed by a talented cast. Even the two child actors deliver strong performances. There’s a lot of emotional depth and complexity, especially when Miyo is reunited with her estranged father, a failed man who is empowered by his ‘lost’ daughter’s courage and determination. Most fans of classic Japanese historical drama would find much to enjoy here. It would sit happily alongside great examples such as Ugetsu (1953), which also had a subtle supernatural strand, and the astonishingly beautiful epic ghost story compendium Kwaidan (1964).

JAPAN | 1969 | 78 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

A young boy is chosen as the defender of good and must team up with Japan’s ancient spirits and creatures of lore to attempt to destroy the forces of evil.

12-year-old, Tadashi (Ryûnosuke Kamiki) awakes from a post-apocalyptic nightmare of a ruined city. In the establishing montage, we learn that he’s still coming to terms with his parent’s divorce and his new surroundings. He’s been parted from his sister, who remained in Tokyo with their father, and he now lives with his mother (Kaho Minami) and grandfather (Bunta Sugawara) in a rural area of the Tottori Prefecture. Tadashi’s voiceover tells us “that summer, I fell in love for the first time, and I told a little white lie…” and sets the scene for what, in many respects, will be a classic coming-of-age metaphor in the format of many a fairytale. However, those comfortingly familiar tropes won’t prepare the first-time viewer for what’s about to unfold!

On hearing a commotion in his cattle shed, a farmer rushes in to find a hideous human-calf hybrid. Still bloodied and dripping from its birth, the creature turns its uncanny face toward him, proclaiming the coming of a great war before shedding a single black tear, and dropping dead. That was Kudan, a cow-born yōkai that only lives long enough to deliver its prophecy, which will always come to pass.

It’s a pretty intense opening gambit that reminds us that Japanese expectations of a ‘child-friendly family film’ differ from the west’s Disney-set norms. That said, The Great Yōkai War is marvellous family viewing, provided the youngsters and adults alike are emotionally robust. It’s an action-adventure rollercoaster that’ll play games with your heart and mess with your head in equal measures as it careers toward an extravagantly weird finale.

It all kicks off when Tadashi goes to a local festival that traditionally culminates in selecting the town’s ‘Kirin Rider’—a bit like being crowned the May Queen in a British village fête. Unexpectedly, he’s chosen and soon sees that it isn’t just a silly bit of rural superstition. Although his grandpa’s losing grip on reality, he’s old enough to remember the traditional tales of the Kirin Rider who must go to the mountain kingdom of the Tengu and retrieve a magical sword needed to defend the world from evil…

Tadashi isn’t brave enough to test the tale by actually venturing up the mountain. On his way home, the night bus is besieged by a visitation of demonic creatures. He probably would’ve dismissed this as another dream if not for the wee beastie that nuzzles his ankle. It’s strange, cute, injured, and needs his help. It turns out only he can see the little thing that looks like a cross between a puppy and a guinea pig. So, to begin with we find ourselves in a familiar storyline where a child finds an animal in need and realises it’s mutual, nursing it back to health in secret. Reminiscent of the recent comedy Flora and Ulysses (2021) which shared the divorce theme and, perhaps unwittingly, features a yōkai in the form of a ‘superhero’ squirrel.

With the aid of his new little friend, Tadashi learns that it’s a Sunekosuri, or ‘the shin-rubber’, and seeks out the Mizuki Shigeru Museum in nearby Sakaiminato City to learn more about the forgotten yōkai. This a real place commemorating the life and works of the revered manga creator whose work inspired the central narrative. He popularised the Sunekosuri as a recurring character in a long-running series of works starring the ghost-boy Kitaro that began in 1954, bringing yōkai back into popular culture for the younger generation. (Remember to look out for his cameo appearance in the film’s finale.)

We know that Sunekosuri was injured when he narrowly escaped being captured by one of the demonic machines unleashed by the immortal oni sorcerer, Yasunori Kato (Etsushi Toyokawa). He’s been enslaving yōkai to power his deadly cyberpunk contraptions made from outmoded machines that have been discarded. These are all things that would’ve developed yōkai of their own but, instead, have become repositories of humanity’s resentment and discontent. With the help of Agi (Chiaki Kuriyama), a yōkai that wants to become human, and fuelled only by vengeance, Kato plans to convert all the yōkai still hiding in the woods, rivers, and mountains, into mechanical slave soldiers and unleash an army to destroy the world of humans. There’s a clear eco massage there!

The arch-villain, Kato, is the creation of author Hiroshi Aramata and has entered into popular Japanese culture since debuting in his 1985 novel Teito Monogatari / Tale of the Imperial Capital. In his origin story, he was born at the moment his mother, the last of his clan, died. He claims to have inherited his magical prowess from the great Abe no Seimei—whose own origin story is told in Tomu Uchida’s beautiful yōkai film The Mad Fox (1962). Yasunori Kato has since become a sort of Japanese Dracula and had already appeared in the films Tokyo: The Last Megalopolis (1988), Tokyo: The Last War (1989), and The Doomed Megalopolis (1991). So, The Great Yōkai War can be seen as his cross-over into the Daiei Cinematic Universe.

Believing his grandfather has been abducted by yōkai and taken to the halls of the Mountain King, Tadashi finally finds his courage and sets out on a rescue mission. Along the way, he meets Kawahime (Mai Takahashi) the beautiful ‘river princess’, Kawataro (Sadao Abe) a brash but well-meaning kappa, and Shojo (Masaomi Kondô) a sea spirit, who reveals the disappearance of Tadashi’s grandfather had been an illusion to galvanise the boy into action. Together, they make their way to meet with the awesome Daitengu (Ken’ichi Endô), who presents the legendary sword of the Kirin Rider to Tadashi. At this point, they’re interrupted by Agi who fights the giant Daitengu. Briefly, Tadashi manages to wield the magic sword and puts up a good fight against Agi’s metal soldiers, which have a definite ‘Terminator’ vibe about them. But, as yet, he’s no warrior and the conflict ends badly with Daitengu defeated, the great sword broken, and Tadashi’s beloved Sunekosuri trapped in a microwave before being whisked away…

The yōkai are all realised using ‘old-school’ techniques including special make-up, excellent prosthetics, mechanical effects, and puppetry. The new machine-yōkai fusions are provided using CGI and this visual clash helps to underpin the central narrative of traditional wisdom being pushed aside by the technology-driven modern world. We know the yōkai are ‘real’, tangible, on set, and interacting with the other actors, so the leap of imagination to accept them really brings the viewer into the magical world. The digital monsters are somehow less convincing, at some level we’re aware that they were not really there. They are a product of a new kind of movie magic. By this point in the film, we believe in the Sunekosuri. Even though he’s clearly a glove puppet, we feel Tadeshi’s pain on being parted from him, thanks to an outstanding performance from Ryûnosuke Kamiki throughout.

And so begins Tadashi’s real quest to reforge the broken blade and learn how to work with its spirit, for the sword is itself a yōkai. Then, he must face his fears and attempt to rescue Sunekosuri, defeat Agi, and then face Kato in his factory fortress that takes flight as a massive, pollution-belching kaiju heading for Tokyo. We know that Tadashi doesn’t stand a chance on his own, but with some help from his new yōkai friends… well, the odds are still against them! I shall say no more, except that it won’t be what you’re thinking!

There are plenty of parallels with The NeverEnding Story (1984), which also used mechanical effects, prosthetics, and puppetry to great effect. The pre-pubescent protagonists in both films are dealing with a recent fracturing of family life, both are bullied by the local kids, and find an otherworldly quest to challenge their self-esteem and build confidence. They encounter an array of strange creatures in a magical realm that help them to defeat a darkness that threatens all mankind. There are similar heart-breaking moments, too, and both films weren’t afraid to pile plenty of potential doom on the shoulders of their young heroes. There’s even a sequence near the finale of The Great Yōkai War that mirrors Bastian’s triumphant flight on Falkor, the luck dragon, at the end of The NeverEnding Story.

Unpredictable director Takashi Miike had already made 30 movies when the Asia extreme horror thriller Audition (1999) brought him to international prominence. His two other films made that same year were Dead or Alive (1999)—an ultraviolent yakuza crime drama remembered for its audaciously crazy, trans-genre ending, and Salaryman Kintaro (1999), a straight-forward live-action adaptation of an established manga series about the leader of a biker gang trying to go straight. He also directed a TV miniseries about schoolgirls uncovering a modelling agency run by vampires which was, it seems, fun and politically incorrect.

So, five years on and another 30 films later—yep, he works hard—it should come as no surprise that he delivers this unpredictable, hugely entertaining, classic of the fantasy genre. If you want a yōkai film, they don’t get better than this. Miike has managed to capture the irreverent ‘spirit’ of the folklore whilst bringing it bang up to date and making it relevant to our modern world. Any yōkai enthusiast will be in their element as they try to spot their favourites. I didn’t count them myself, but there are reputedly more than a million of them in one shot, combining 600 extras backed up with additional CGI hordes.

The Great Yōkai War is an unmistakably Japanese spectacle that was well-received on release and selected for the 62nd Venice Film Festival. It did well at the box office but not well enough to warrant a direct sequel. Until now. The Great Yōkai War: Guardians, again with Takashi Miike directing, was released late summer 2021…

JAPAN | 2005 | 124 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

directors: Kimiyoshi Yasuda (100, Ghosts) • Yoshiyuki Kuroda (Warfare) • Takashi Miike (Yōkai).

writers: Tetsurô Yoshida (100, Warfare, Ghosts) (based on the folk tales of Momotarō and ‘The Great Yōkai War’ by Shigeru Mizuki) • Takashi Miike, Mitshuhiko Sawamura & Takehiko Itakura (Yōkai) (based on the novel by Hiroshi Aramata).

starring: Shinobu Araki, Jun Fujimaki, Ryûtarô Gomi (100) • Pepe Hozumi, Masami Burukido (Ghosts) • Yoshihiko Aoyama, Hideki Hanamura & Chikara Hashimoto (Warfare) • Ryûnosuke Kamiki, Hiroyuki Miyasako, Chiaki Kuriyama (Yōkai).