THE MAD FOX (1962)

In the reign of the Emperor Suzaku (930-946 A.D), various mishaps happen after a strange white rainbow appears in the sky over Kyoto.

In the reign of the Emperor Suzaku (930-946 A.D), various mishaps happen after a strange white rainbow appears in the sky over Kyoto.

The Mad Fox is the latest classic to join a run of boutique Blu-ray releases from the inventive and influential country of Japan. This time we have Arrow Films to thank for ensuring cineastes have a chance to discover or reassess a most welcome addition.

I’m not sure if the title, The Mad Fox, really suits this beautiful and bittersweet romantic fantasy. It creates expectations of rogue samurais or superhuman swordplay in the wuxia tradition, perhaps due to a westerner’s cultural distance and expectations. If that’s what you want, there’s plenty elsewhere. Wonderful as wuxia is, The Mad Fox is entirely different—possibly unique for the time it was made, it remains difficult to categorise.

The fox reference would also be a dead giveaway to Japanese filmgoers of the 1960s just as much as it is today. Kitsune are ‘fox spirits’ and rank among the most powerful beings in Japanese folklore. In terms of cultural prominence, they’re along the same lines as a vampire, zombie, or werewolf. The Mad Werewolf!?

In the mythology and folklore of Japan, foxes or ‘kitsune’, are magical creatures, neither good nor evil—though famous tricksters. They can travel in the form of fire and the term ‘foxfire’ originates with them—another name for will-o’-the-wisp. They can also shapeshift into the form of a person and live out an entire life posing as a human.

Chinese and Japanese stories featuring kitsune are as popular and varied as western fairy tales. Many tell of vixens falling in love with men, even marrying and having families. They inspired several Pokémon such as Vulpix and Ninetales, too. “Megitsune“, a 2013 single by J-Metal group BabyMetal, is about the feminine power of the vixen goddess.

Currently, a series of Japanese television commercials for Nissin noodles track the developing romance between a kitsune lady and a young man that have bonded due to their mutual love of ramen and fried tofu! It’s no coincidence that fried tofu is traditionally left as offerings to kitsune at their shrines in Shinto temples.

Those adverts offer a post-modern take on one of the most popular kitsune folktales, about a young boy who helps an injured fox cub and releases it back into the wild. He doesn’t realise it was no ordinary fox, but a kitsune that watches him grow up and one day returns to him as a pretty young lady. Romance ensues and they later married. Bear with me, the relevance will become apparent…

That’s probably why the film’s director, Tomu Uchida, called his movie Koi ya Koi Nasuna Koi—which has been translated as Love, Thy Name Be Sorrow. That’s certainly not accurate, because ‘koi’ means ‘love’ and is mentioned three times there, which would be fitting as the story contains three definite intertwined love stories that drive the entire narrative. And yes, I fully understand why that title wasn’t favoured by the marketing departments of the west. Though, even in its rough translation, it better represents the story’s poetic and emotionally charged aspects than the one we’ve had foisted upon us.

The story took a strange and circuitous journey from its origins to this screen version and draws upon several different sources. It’s been described as an adaptation of a play written by Takeda Izumo for the famous Takemotoza Bunraku Puppet theatre, which the playwright founded in Osaka during the mid-18th-century. He based his story on a mix of historical fact and folklore found in ancient manuscripts surviving from the Heian Era of classical Japan, which spanned from the 8th to the 12th centuries—a period remembered for its art, poetry, and rise of both Buddhism and Bushido beliefs, alongside the indigenous Shinto religion. The relatively peaceful period ended with the tragedy of the Genpei War.

The most prominent proponent of Japanese folklore, Lafcadio Hearn, also studied those manuscripts and went on to write the tales that inspired another great Japanese film, Masaki Kobayashi’s Kwaidan (1965), which dealt with the ghosts of the Genpei War and could easily be viewed as a sequel to The Mad Fox, or even an extension. Especially when one considers the writer of The Mad Fox, Yoshikata Yoda, also wrote Kenji Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu (1953), which incorporated the same folktale that part-inspired Kwaidan.

Both films have so many similarities in narrative structure, subject matter, and visual styles, that it’s clear that Kwaidan (one of the greatest of all Japanese films) must have been influenced by The Mad Fox. Each is comprised of distinct sections but whereas Kwaidan was a portmanteau of four separate short stories, The Mad Fox tells its story in three distinct acts linked by a single protagonist.

Following an extended opening section in which a narrator tells a traditional story from a picture scroll that pretty much prefigures the first act, we join the Ying-Yang Master Kamo no Yasunori (Jun Asami) who watches the sky turning an ominous blood red, due to ashes being spewed from the grumbling volcano of Mount Fuji.

Yasunori is a real historic person who was a renowned astrologer to the royal court. His depiction here, though, is more closely based on the traditional Kabuki play about him, Ashiya Dōman Ōuchi Kagami / A Courtly Mirror of Ashiya Dōman. Kabuki is a highly stylised form of theatre known for its use of masks, elaborate costumes, and being a fusion of opera, dance, and mime.

Yasunori consults his sacred ‘Scroll of the Golden Crow’ (again based on a real and highly influential scroll about divination) and immediately sets out to tell the Emperor his interpretations of the omens in the sky but is shockingly murdered shortly after leaving. This means the duty of interpreting the signs for the royal court must fall to one of his disciples: the wise and gentle Abe no Yasuna (Hashizô Ôkawa), or the ambitious and scheming Ashiya Dōman (Shinji Amano). But the old seer died without naming a successor and has no son to automatically inherit his role.

His adopted daughter, Sakaki No Mae (Michiko Saga), loves Yasuna and claims that Yasunori had named him as the successor, but the old master’s wife (Sumiko Hidaka) points out there’s no record of this and so favours Dōman. Now, this is where The Mad Fox has fun blending fantasy, folklore, and history into a fresh narrative… for the scroll and the main players are all inspired by real people and documented events, but over the centuries they’ve become mythologised too.

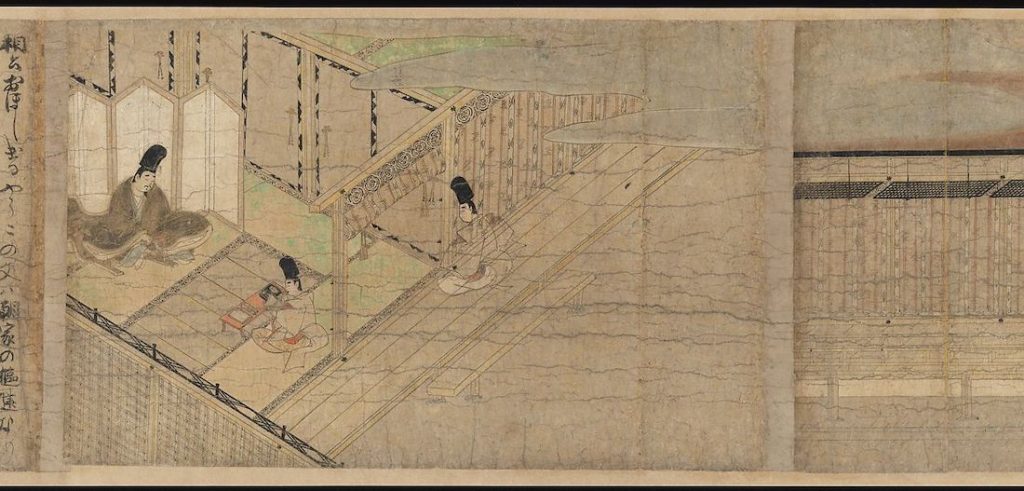

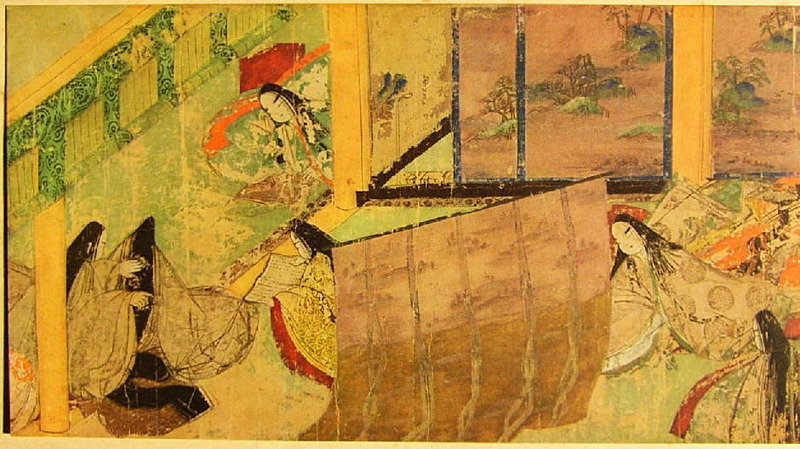

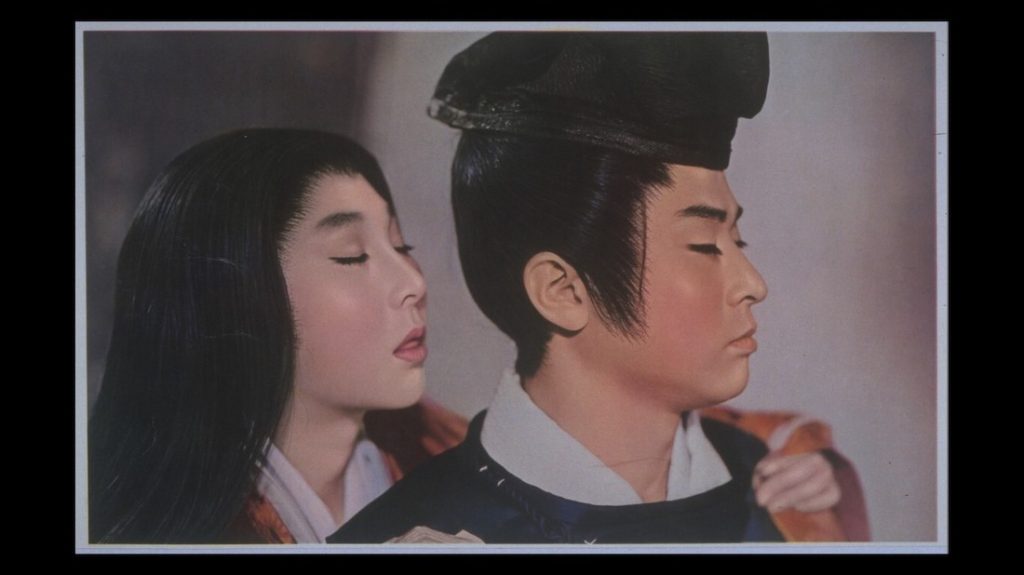

It’s utterly absorbing and beautifully constructed, with each shot echoing the compositions of classical paintings and prints from the era in which it is set. Tomu Uchida exploits the widescreen format to great effect and often the camera moves across the scene as if revealing a scroll painting. His cinematographer, Sadaji Yoshida, used relatively new anamorphic lenses and took great care to keep traditional perspective to a minimum; flattening the image into beautifully balanced, illustrative compositions. Such lenses were still experimental and there is, unfortunately, some distortion. Often the focus isn’t all that sharp. I’m not sure if it’s a fault of the lenses or if some scenes were shot through gauze to soften them, which does lend a sort of unreal, dreamy feel.

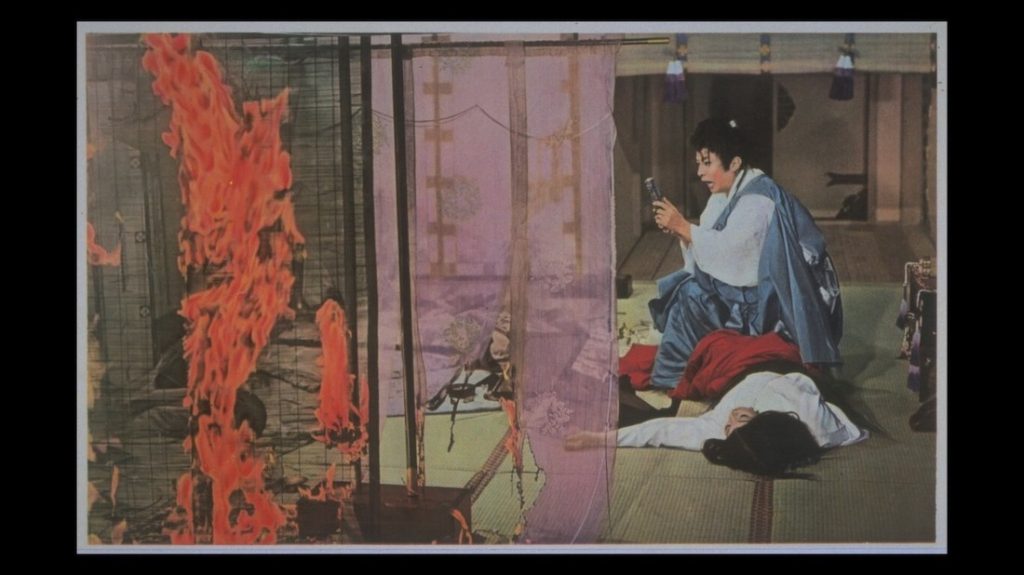

Act I is a fairly straightforward family drama of intrigue, machinations, and powerplay. It’s subtly hinted that one of the characters may be a demon in disguise and ends in tragedy and madness. Act II is a change in pace and aesthetics, opening with the now insane Yasuna wandering aimlessly and dressed in Sakaki’s kimono.

Hashizô Ôkawa’s Kabuki training really comes to the fore as he mimes the fusion of masculine and feminine. Traditionally, only male actors perform kabuki and female roles are taken by specialised actors like Ôkawa. This section really celebrates the artifice of cinema with rotating sections of stage and set almost saturated with primary yellow, suggesting a meadow of chrysanthemums. The fluttering butterflies are clearly puppets with no attempt to conceal their strings. Just like the mind of the character, we’ve detached from reality… I found this theatrical sequence astonishingly beautiful and unexpectedly affecting… though the narrative, sung in the style of Japanese opera, might be too much for many western ears!

When a veil literally falls from before our eyes, we find ourselves back in a real location, seemingly without an edit. Yasuna’s crazed wanderings have led him to find Sakaki’s twin sister, Kuzu No Ha (also Michiko Saga), whose family take him in. Although he believes that she’s her sister, Kuzu falls for his gentle sensitivity and, for the sake of his happiness in oblivion, plays along with his delusions. That is until they get caught up with a fox hunt and help an old woman injured by a stray arrow.

Yasuna tends to the victim’s wounds and gets her safely back to her hovel in the woods where she lives with her husband and their granddaughter, whom they send after Yasuna to make sure he comes to no harm on his return journey. Of course, he comes to some harm and the granddaughter returns the kindness he showed her grandmother by nursing him back to health.

However, when instead of dressing his wounds she licks them clean… our suspicions are confirmed. To hide her true form, which Japanese audiences would’ve guessed well ahead of any reveal, she has assumed the likeness of Sakaki / Kuzu (Michiko Saga again). What Yasuna had attempted to do previously by wearing her kimono, this kitsune does through powerful magic… it’s all very poetic and beautiful. As is Michiko Saga in her triple role.

Like most of the cast, Saga was well-known in Japanese cinema of the time, though only a few faces would be at all familiar to western audiences. I recognised Jun Asami, in the role of the old seer, not for his international role in Richard Fleischer’s classic war drama Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970), but from his appearance in Michio Yamamoto’s Vampire Doll (1970), the first in the so-called ‘Bloodthirsty Trilogy’ of Japanese vampire movies. And viewers of a certain age may remember Rin’ichi Yamamoto, who plays a sadistic villain here, from the TV adaptation of James Clavell’s Shogun (1980).

As Act III opens, an actual curtain is drawn back across the screen to reveal what is clearly a theatrical set. We now cross fully into folklore and Uchida relinquishes all pretence of reality. The use of such obvious staging is a visual style that Kwaidan would borrow and take to another level. It’s an approach that remains fresh and inventive even today. Older foreign films often surprise with innovations that would only become normalised in western cinema decades later. To the Japanese, though, it’s clearly embracing the traditional kabuki style of storytelling and may well have been reassuringly familiar.

If the viewer has made it this far, they’ll be completely enchanted. Rather than breaking the spell, this clever use of artifice encourages the viewer to fully engage with and enter into the narrative. We’re seduced into taking on more responsibility for the storytelling ourselves. The VFX of today can make pretty much anything seem convincingly ‘real’ but the efforts are also easily dismissed. We know it’s artificial. The use of traditional kitsune masks, mechanical effects, moving sets, obviously painted scenery, a doll in place of a baby, and so on, forces us to suspend disbelief. There are even a few beautiful sequences of traditional cell animation from the Toei Animation studios. Don’t get too excited, though, these are well-placed but all too brief.

For those who can engage their imagination, the experience becomes irresistibly immersive. In a way, just as the avant-garde artist Marcel Duchamp said, “it is the viewer that completes the art,” so the viewer completes this film within in their poetic imagination. Such is its power that the audience may even extend it into their own dreams…

If the ending seems too dreamy and baffling, then this would again be down to cultural dissonance. To an average Japanese filmgoer, the events of the finale all fall nicely into place with overt references to their folklore and popular mythology. To them, the denouement reveals the film to have been the ‘origin story’ of one of their iconic characters, who began as a real person and whose exploits have been embellished through millennia of folklore. A western analogy would be for a film to close with a young boy discovering a woodland glade in which he pulls a sword from a stone…

It certainly left its indelible stamp on the unrolling scroll of Japanese cinema by melding a relatively new art, plus and few technical innovations of its own, with the traditional art and aesthetics of the previous thousand years. The Mad Fox, along with a handful of similar Japanese films made in the early ’60s, also left an impression on western filmmakers. A technique of using sets and lighting to highlight sections of the screen and even to achieve the effect of an edit, not by cutting the film but by a dramatic change in lighting, is evident here as it was in Kwaidan.

The same approach can be seen throughout the key work of Francis Ford Coppola, notably in Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), and particularly his musical One From the Heart (1982), which used the method prominently and also relied on evoking a sense of magical realism by having the film shot entirely on a specially designed set.

George Lucas is also known to be hugely influenced by Japanese cinema and I suspected that his old Jedi Master, Yoda, was named in tribute to this film’s influential scriptwriter, Yoshikata Yoda! It was nice to have this confirmed by the full-length audio commentary recorded especially for Arrow’s new Blu-ray release. It’s great to see some of these beautiful and important Japanese films being rescued from obscurity and made available in the home media market. Arrow, along with Eureka Entertainment and Criterion, are doing a fine job so far… but I suspect there’s much work to be done and plenty similar gems that need to be afforded the respect of loving digital restoration like this!

JAPAN | 1962 | 109 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

Extras are light for a so-called Special Edition. Arrow Academy sadly missed the opportunity to include an image gallery comparing examples of the art from the Heian period with shots from The Mad Fox. The artwork’s in the public domain, so this would’ve been easy to do and would have celebrated an aspect of the film easily missed by a casual viewer. A couple of examples:

director: Tomu Uchida.

writer: Yoshikata Yoda.

starring: Hashizô Ôkawa, Michiko Saga & Ryûnosuke Tsukigata.