DER GOLEM (1920)

In 16th-century Prague, a rabbi creates the Golem, a giant creature made of clay, and uses sorcery to bring it to life to protect the city's Jews from persecution.

In 16th-century Prague, a rabbi creates the Golem, a giant creature made of clay, and uses sorcery to bring it to life to protect the city's Jews from persecution.

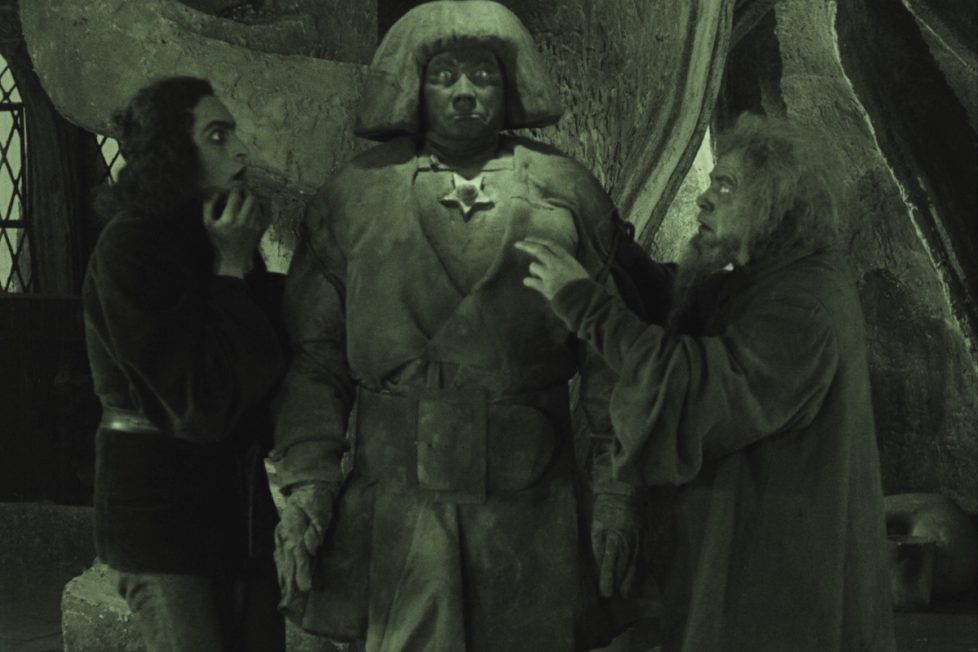

Considered an urtext of Weimar German Expressionist cinema and silent horror, Paul Wegener’s Der Golem, wie er in die Welt kam (1920) receives a welcome HD release from Eureka’s ‘Masters of Cinema’ series this month. It was one of many Expressionist films to have a significant impact on Hollywood horror and film noir in the 1930s, under the influence of many German filmmakers who’d opted to continue their careers in America after the Nazi party rose to power.

Wegener’s Der Golem was, like many Expressionist German films of the era, a response to the Weimar Republic’s post-war political, economic, and social instability. These films reflected a specific movement—led by artists, architects, designers—that valued experimentation and abstraction and the disconnection between subjectivity and reality. They articulated the anxieties and uneasiness of the time and often explored the darker themes of crime, corruption, disfigurement, decay, and the extremes of human behaviour in an increasingly technological society filled with chaos and distrust. Key films of the period included Robert Weine’s hallucinatory horror Das Cabinet des Dr Caligari (1920), where Weine recruited Expressionist painters Walter Reimann and Hermann Warm to create the sets, and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927), a modernist science-fiction parable of class warfare and the troubling interface between human heart and cold machine.

Wegener, having rejected the study of law, instead followed his instinct for writing and performing and briefly joined the Rostock theatre company as an actor, only losing the contract when he had an affair with a married woman. He then worked in various companies across Germany until he came to the attention of impresario and director Max Reinhardt. At Reinhardt’s Deutsches Theatre in Berlin, Wegener sealed his reputation as a leading actor of his generation. While playing in Berlin, Wegener cultivated other interests and a particular fascination for cinema. He believed in the potential of visual effects, then in their infancy, to liberate film as an art form—distinct from the conventions of the stage.

Using these effects, he believed artists would have a license to articulate their dreams and nightmares and capture the romantic tradition in German art. To this end, he collaborated with director Stellan Rye on one of the key films of early German cinema, Der Student von Prag (1913). This tale of a student haunted by his own reflection (a mirror image stolen by a sorcerer after making a pact with him in order to woo a young Countess) anticipated what James Donald described as the “primarily romantic motif - Faustian, Promethean, Frankensteinian” that would echo throughout Der Golem and Metropolis and later re-emerge in James Whale’s masterpiece Frankenstein (1931). The growing sense of alienation and disconnection in German society, as the First World War dominated the cultural zeitgeist, extended into the staging, lighting, and visual effects of the production to create an early iteration of the dreamlike Expressionism that would dominate key fantasy films in Weimar Cinema.

While making Der Student with Rye, Wegener became familiar with the legend of the Golem, a Jewish folk tale he felt would be an appropriate subject for his next film. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, the idea of the Golem (a reanimated artificially-created being) can be traced back to ideas in the Old Testament about creating embryonic substances (the creation of Adam is considered one of the first Golem narratives) and the Talmud. A number of Jewish folk legends told of wise men bringing to life an inanimate effigy by placing sacred words or one of the names of God inside the statue’s mouth or attached to its head. The creature could then be deactivated by removing the charm.

Various Golem tales transferred from Jewish antiquity and were introduced into Christian texts. These established the Golem as a popular literary figure and included the story of the Golem of Chełm, originally related in a 1674 letter by folklorist Christoph Arnold, which would rematerialise later in 1808 when Jacob Grimm reinterpreted it for Achim von Arnold’s journal Zeitung für Einsiedler. Arnold would transpose Grimm’s reportage of the original folk tale into his novella Isabella of Egypt (1812), the first to feature a female Golem and use it as a doppelganger figure. It’s ironic that the Jewish legend of the Golem was introduced to 19th-century German culture by the antisemitic Grimm and Arnold and that these Golem stories, emerging during Europe’s own infatuation with German Romanticism, went on to influence Mary Shelley’s ideas for Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus when she set about writing her book on the shores of Lake Geneva in 1816.

The most influential version of the story was a 16th-century folk tale (regarded as the classic ‘Golem of Prague’ story) featuring the renowned Talmudic scholar and philosopher Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel (known as the Maharal of Prague), who activated the Golem using Kabbalistic incantations to protect the Jews in the Prague ghetto from antisemitic persecution. This folk narrative was actually a German literary invention that originated from a number of Romantic writers of the early 19th-century and were later introduced into the mainstream, in response to Grimm and Arnim’s versions of the tale, with several spin-off bestsellers: Yehuda Judel Rosenberg’s The Golem and the Wondrous Deeds of the Maharal (1909), Gustav Meyrink’s Der Golem (1915), and Chayim Bloch’s Der Prager Golem (1920).

Unrelated to these publications, Wegener starred in Der Golem (1915), the first of his three film versions. He co-directed and co-wrote with Henrik Galeen, who would write Murnau’s German Expressionist horror classic Nosferatu (1922) and eventually direct the 1926 remake of Der Student von Prag. Using a contemporary Prague setting, it tells of an antique dealer discovering the clay statue of the Golem in a ruined Jewish temple. He revives it, employing it as his servant, but when he attempts to use it to prevent his daughter falling in love with an aristocrat, the Golem goes on the rampage. It’s considered a lost film but the surviving fragments clearly show Wegener playing the Golem in a costume very similar to the one he would use in his 1920 version, which in many respects is actually a prequel to this film. In 1917, Wegener then starred in and co-directed Der Golem und die Tänzerin (The Golem and the Dancing Girl) where he gave the story a modernist comic spin, a meta-textual spoof on his earlier effort, with a story about an actor, played by Wegener, who dresses up as the Golem to try and frighten a young dancer he is infatuated with. Again, this version is considered to be lost.

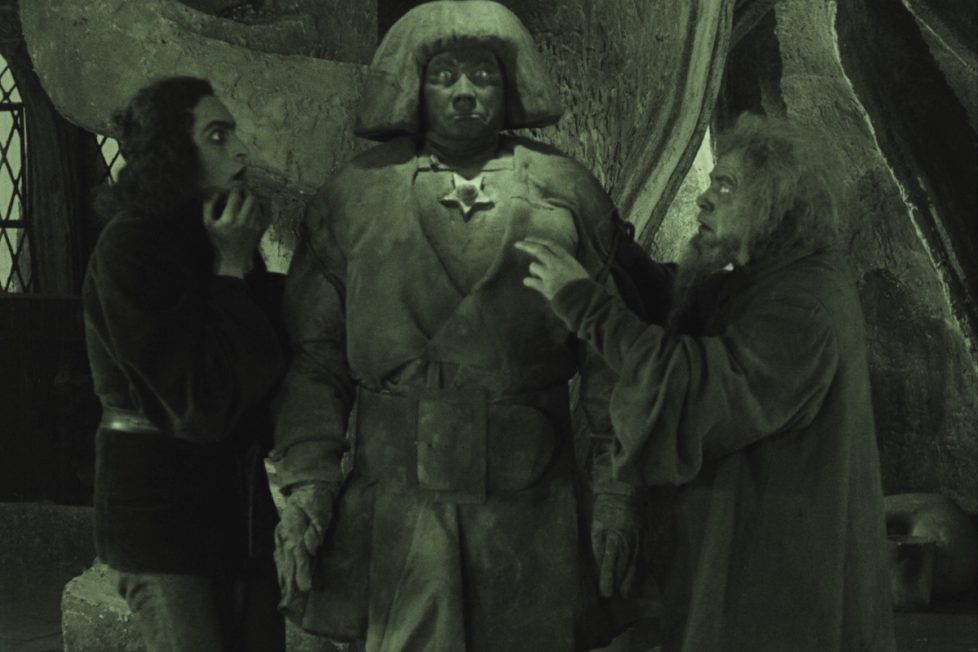

Der Golem, wie er in die Welt kam (The Golem, How He Came into the World) saw Wegener starring, co-directing with Carl Boese, and again co-writing with Galeen. The script combined elements of the Golem of Chełm tale, the folk tale he had heard about during the filming of Der Student, the Meyrink novel, and the classic German legend of Faust. He returned to the story’s 16th-century Prague setting to create a Golem ‘origin’ story, one referred to in flashbacks in the 1915 version. Rabbi Loew (Albert Steinrück), having foreseen impending disaster for the Jewish community in the ghettos, builds the clay figure and communes with the demon Astaroth to acquire the magical word to animate his Golem (Wegener). It is enclosed in an amulet and attached to the clay figure’s chest. At first, Loew uses his Golem as a servant. However, the creature starts to gain a sense of self-awareness.

Although Emperor Rudolph (Otto Gebühr) is planning to issue an edict that expels all Jews from the ghettos of Prague, he invites Loew to a festival at his castle to perform magic tricks. Loew takes the Golem with him and relates the history of the Jewish patriarchs to the royal court’s audience, to much mockery. Insulted, he brings the roof down on them. He uses the Golem to hold the collapsing ceiling up, saving everyone at the court, and the grateful Emperor rescinds his edict. The Golem is deactivated and the ghetto celebrates the repeal.

Meanwhile, a love triangle between Loew’s daughter Mirjam (Lyda Salmanova), his assistant Famulus (Ernst Deutsch), and the Emperor’s knight Florian (Lothar Müthel), sees Famulus’ jealousy turn to violence when he reactivates the Golem, now repossessed by the demon Astaroth, and orders it to remove Florian when he finds him in flagrante delicto with Mirjam. However, the Golem throws Florian off the roof and kills him, sets the house on fire and goes on the rampage through the ghetto, dragging Mirjam with it. As the Golem breaks through the gates of the ghetto, Loew uses his magic to quench the fire, and the clay figure is rendered inanimate after it picks up a child playing outside the gates and the young girl, out of curiosity, removes the amulet in its chest.

The new ‘Masters of Cinema’ Blu-ray presentation of the Murnau Foundation’s 4K restoration is an engaging viewing experience and provides a fresh and powerful reunion with an often-overlooked film; one key to the development of Weimar Cinema and the evolution of the classic horror films produced by Universal. Beautifully restored in all its tinted glory, the film resonates with images that are now familiar to us through their re-purpose in later films, especially Whale’s Frankenstein. Wegener’s portrayal of the Golem, a huge lumbering clay automaton who betrays a sense of self-determination and sensitivity, must have influenced Karloff’s appearance and performance. This is particularly evident when the Golem goes on the rampage and meets the child at the film’s denouement, echoing similar scenes in Whale’s movie. Wegener is joined by several ex-Deutsches Theatre actors: Wegener’s wife Lyda Salmanova, Gebühr, Deutsch and Steinrück, all of whom offer good performances and underline the amorality of the major characters. The affair between Mirjam, a Jewish woman, and Florian, a Gentile nobleman, is at first rendered as innocent but then becomes furtive and seedy as the story progresses, perhaps feeding into the antisemitic undercurrent of the film.

This unease is emphasised when, at the end of the film, the jealous Famulus entreats Mirjam to cover up their misdeeds, which led to the Golem almost destroying the ghetto. As Cairns notes in his video essay on this disc, the film is both sympathetic and ambivalent to the Jewish characters. The “flighty, inconsistent” Emperor, keen to hire the Rabbi for some magic tricks at his festival, discriminates against the Jewish community by aligning them with illicit black magic practices, “which is then shown to be true” when the Rabbi conjures up Astaroth in a spectacular sequence at the start of the film. This uneasy equivocation culminates with the end of the film, as the Jewish community reclaim their inanimate clay man, after it has been felled by an innocent, blonde-haired child outside the ghetto, and immediately return behind their city walls as the Star of David is superimposed on their departure. They are literally sealed back into their ghetto.

The film is full of powerful, beautifully composed images. From the aforementioned raising of Astaroth, through to the Golem’s creation, its rescue of the festival-goers by holding up the ceiling, to its rampage through the ghetto, Wegener’s film is served well by a number of technicians, who had worked on his previous films, and here underpin the way Expressionist artists and designers collaborated with filmmakers in this period. Rochus Gliese’s costume for the Golem incorporates the recognisable design as originally created by Expressionist sculptor Rudolph Belling, for example. The cinematography, including the many innovative visual effects shots, was a collaboration between Wegener, co-director Boese, and Karl Freund, who would cement his reputation as a cinematographer with Lang’s Metropolis, Murnau’s The Last Laugh (1924) and Tod Browning’s Dracula (1931), before directing Karloff in The Mummy (1932).

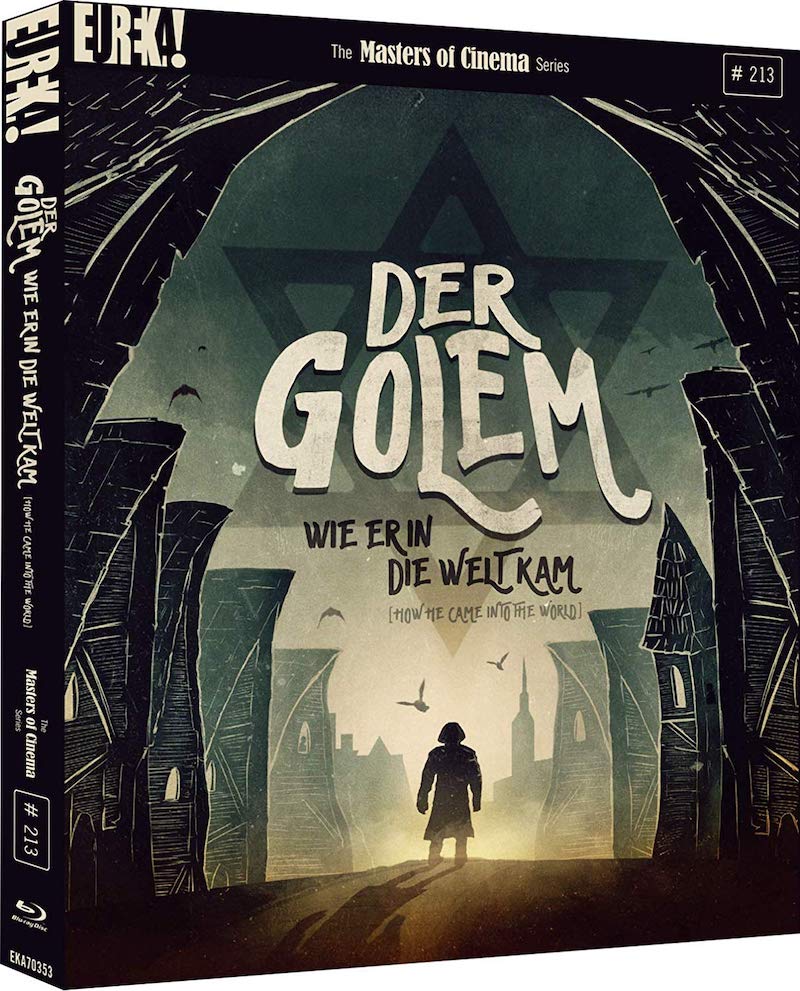

Wegener transfers the dramatic lighting effects he had seen at Reinhardt’s theatre to the film and gives them a thrilling cinematic form. The lighting, together with the sets designed by architect Hans Poelzig, also cultivates the film’s Expressionism which is, as noted by John R. Clarke, “developed in organic rather then abstract, Cubic forms” and was a “tangible, plastic expressionism” that offered a naturalistic approach to the “unexpected shifts of the streets, the winding of the stairs, the proliferation of ‘Gothic’ ornamentation” in the buildings that made up this fantastical medieval Prague ghetto. That image of the ghetto also renders the film as an off-kilter, morally ambiguous, dark fairy tale in tune with the 19th-century resurgence of German Romanticism.

directors: Paul Wegener & Carl Boese.

writers: Henrik Galeen & Paul Wegener (based on the novel by Gustav Meyrink).

starring: Paul Wegener, Albert Steinrück, Lyda Salmonova, Ernst Deutsch & Lothar Müthel.

I am indebted to the following articles and books: