KWAIDAN (1964)

A collection of four Japanese folk tales with supernatural themes.

A collection of four Japanese folk tales with supernatural themes.

Kwaidan is a film cinephiles instantly recognise from its distinctive imagery, even if they haven’t seen it themselves. I was in that category until recently, having first seen stills from it decades ago when my obsession with cinema was first manifesting. I borrowed film books from the library and friends, and snapped-up any I could afford from my local bookshop. Back then, I hadn’t developed a penchant for full-blooded horror, but I was certainly attracted to the cinema of mystery and imagination. I loved weird and stylish supernatural thrillers and, as far as I could tell from those books, Japan had produced some real classics.

David Annan’s book Cinema of Mystery and Fantasy came out in the mid-1980s when I was starting to study filmmaking at college, and that was probably where I first saw photos from Kwaidan. Although poorly reproduced and not accurately credited, their powerful simplicity lodged in my mind, especially the close-up of a man’s anguished face, entirely covered with Japanese writing.

That book pretty much became my watchlist. But what chance was there of tracking down obscure foreign films like Kaneto Shindô’s Onibaba (1964) and Masaki Kobayashi’s Kwaidan? Indeed, the version of Kwaidan most widely distributed outside Japan was missing more than an hour of material! So, even if it had come to an arts theatre near me, I still wouldn’t have been able to see the entire film.

There have been a few boutique releases on VHS and DVD, but they’ve been missing significant chunks too. The first time the full-length ‘Director’s Cut’ was available outside of Japan was the Criterion 2K restoration on Blu-ray, now available through Eureka Entertainment’s ‘Masters of Cinema’ label in the UK. A most welcome release in a handsome Limited Edition that includes a 100-page Collector’s Book. Better late than never! The film’s as old as I am, and I’ve been waiting to watch it since those striking images sparked my imagination more than three decades ago. Is it the masterpiece I’ve been hoping for? Yes.

As well as including Linda Hoaglund’s overview of the life and works of Masaki Kobayashi and a reprint of his final interview, the aforementioned Collector’s Book also reproduces the original stories by the renowned folklore scholar Lafcadio Hearn. Screenwriter Yoko Mizuki selected four of his tales to adapt for the screen: “The Reconciliation” from Shadowings (1900), “In a Cup of Tea” from Kottō: Being Japanese Curios, with Sundry Cobwebs (1902) and “The Story of Mimi-Nashi-Hōichi” and “Yuki-Onna”, both from Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things (1903).

Rather than weaving them together into some sort of overarching narrative, she kept fairly faithful to the original texts, with the film being an anthology in four distinct segments. In many ways similar to the format established by Ealing Studios’ Dead of Night (1945), Roger Corman’s Tales of Terror (1962) and Amicus’ Dr Terror’s House of Horrors (1965) directed by Freddie Francis, which was in parallel production on the other side of the world and ended up being released the same time, February 1965.

At its heart, Kwaidan is about stories and their telling. What they say about those who perpetuate them, and what our responses to them say about us. The arty title sequence illustrates this premise from the first frames as black writing ink is seen dripping into water.

This is the raw material of the stories we’re about to see adapted for the screen. Not only that, but ink and writing are also to feature prominently in two of the tales. Drops of coloured inks join the black, vibrant and almost calligraphic in their swirling forms. The red suggests blood and links visually with a shot later in the film when waters do indeed turn red with the blood of battle. Kwaidan was director, Masaki Kobayashi’s fourteenth film, and his first foray into colour. He uses colour as a formal element most prominently in the middle two segments.

Based on the short story “The Reconciliation”, this opening tale concerns a poor ex-samurai (Rentarô Mikuni) who makes even poorer life choices. Dissatisfied with the meagre income his loving wife (Michiyo Aratama) brings in with her weaving, he leaves their tumble-down house in pursuit of fame and fortune.

He later finds employment in a wealthy court and even attracts the eye of the family’s daughter (Misako Watanabe), whom he proceeds to marry. She turns out to be rather cool and vain and, ironically, covets the kind of fine fabrics his first wife used to weave.

He soon realises he misses his ex and thinks about her all the time but he’s signed up for a full term of service with his new lord and master. Eventually, when his contract is fulfilled, he returns to his first home to find his wife has waited for him all this time…

In “The Black Hair”, the audience knows something isn’t quite right when Kobayashi brings in his ‘trademark’ Z-axis camera work; a stylish tracking motion that gives the impression of being on a ship at sea, providing a disconcerting disjoint to reality. It’s a deliberate distortion of normal perception that draws our attention to the camera and the fact that what we’re seeing, and how we are seeing it, is under the control of another. We’re not being presented with a window onto a representation of reality with the expectation we’ll accept it as such. We’re made aware of watching fiction. This is a story being told and the teller is choosing how the viewer receives it.

The story is a variation of the same folk tale that runs through Kenji Mizoguchi’s impressive and influential Ugetsu (1953). Shared ingredients include a man leaving a woman to seek wealth and honour and bigamously marrying a richer woman before realising they have their priorities all wrong and returning to their first wives in the hope of reconciliation. I can’t go into details without revealing the various twists and turns, but both blur the boundaries between the living and the dead and both have similar, unexpectedly emotive endings.

The finale is unnerving because it’s so emotionally confusing. The ghost is not necessarily driven to kill by evil impulse and may be motivated by a love that transcends death. A theme that runs through all the stories here is the longing of the dead for life, and that longing being detrimental to those still alive. And also, in a typically weird Eastern way, gyaku mo dōyō (vice versa).

It also contains the most obvious horror imagery: a decaying corpse, a skull, and the titular disembodied clinging black hair. This may have been put up front in the first story to appeal to Western audiences and give them something recognisable to latch on to.

Kobayashi was enjoying newfound recognition in the West having recently won the ‘Jury Prize’ at 1963’s Cannes Film Festival for Harakiri / Seppuku (1962), and his desire to capitalise on this success drew him to the writings of Lafcadio Hearn, a westerner who spent his later life as a Japanese citizen studying the folklore and customs of Japan. He published his stories successfully in the UK and US. So those familiar tropes also touch upon some traditional Japanese lore, including a couple of the creepiest…

There’s a sub-genre of Buddhist art known as Kusōzu, delicate watercolour paintings of predominantly women’s unburied corpses in various stages of decay. (Google that if you’re feeling exquisitely gruesome!) This has a resonance with the western tradition of medieval memento mori paintings and the later ‘graveyard-school’ of the Gothic revival. All serve to remind us of the transience of life and to encourage us to focus on the important things and to value the moment.

The hint of necrophilia, also a fascination in Japanese mythology, is touched upon here. It evokes dread similar to that of Leslie Megahey’s Schalcken the Painter (1979) which borrows some of Kwaidan’s visual motifs but adds its own much darker baroque accents and with overt references to European art instead of Oriental. Kobayashi was a scholar of art history and, perhaps not coincidentally, his mentor in the visual arts was taught English by the author Lafcadio Hearn.

The black hair motif is something that any J-Horror aficionado is now very familiar with after seeing films like, Ringu / The Ring (1998) and Ju-On / The Grudge (2002), but the strange symbolism of long black hair goes right back to the formative films of the J-Horror genre and really starts here with Kwaidan.

It’s a motif taken from the rich folklore of Kami—the Shinto equivalent to angels and demons. The Kamikiri take the form of foxes or giant insects and can possess humans. They’re the hair-cutting demons who stealthily cut-off the long pony-tails of women without them noticing. The longest and most luxuriantly glossy are the most prized and one can only guess at the motivations of these strange spirits! There are several stories about the hair becoming animated and being sent on mysterious missions… so disembodied hair may not be particularly scary to westerners but would be embedded in the psyche of a Japanese audience.

Michiyo Aratama’s long black hair would certainly attract a Kamikiri and Kobayashi capitalises on this by filming her mainly from behind or obliquely so hair frames her perfect profile. She was a big star of Japanese cinema at the time and had worked with the director a few times before, most notably starring in his 10-hour war epic The Human Condition (1959-1961) released as a trilogy. But I recognise her as the female lead in Kihachi Okamoto’s excellent film about a psycho samurai, The Sword of Doom (1966).

In folklore, Yuki-onna is a spirit of the winter snows; a sort of Japanese equivalent to Hans Christian Anderson’s Snow Queen, the White Witch of Narnia, or Elsa from Disney’s Frozen franchise. Depending on the tale and the teller, she’s sometimes portrayed as an evil vampiric creature who preys on travellers: summoning blizzards so they lose their way in the mountains. And she offers the seductive promise of warming themselves against her beautiful body, only to instead drain all the remaining warmth from their blood and consume their life essence.

In other versions, she’s a tragic character who craves human love and warmth but is cursed so that her freezing breath kills. Sometimes she’s a spirit of mercy appearing to snowbound travellers who’ve lost all hope of finding their way home. She comforts them as she absorbs their warmth, inhaling their last breath as they slip into a peaceful, painless sleep.

The Yuki-onna that appears to the two lost woodcutters in the second segment has several of these attributes, though it’s not immediately clear if she’s evil or not. She’s just one the numerous yōkai in Japanese mythology which are all metaphors for natural phenomena and forces and can’t really be considered good nor evil.

Woodcutters are a staple character of folk tales and fairy stories the world over because they venture out into the wild areas when others won’t. In this tale, an old woodsman (Jun Hamamura) and his young apprentice, Mi (Tatsuya Nakadai), are caught out in a sudden heavy snowfall and seek shelter in an abandoned cabin on the shore of a frozen lake.

After slipping into unconsciousness, Mi briefly awakes to see an ethereal woman dressed in a snow-white kimono. She bends over his older companion and freezes him solid with her frosty breath. As she’s about to do the same to Mi, she hesitates, seemingly beguiled. She can’t bring herself to take the life from one so young and handsome, so whispers that she will spare him if he promises never tell anyone…

It isn’t made clear if the old woodcutter was Mi’s father, but if he was then his mother (Yûko Mochizuki) doesn’t seem all that cut-up about the loss. Either that, or there was a long time between those fateful events in the snowbound cabin and when she finally manages to nurse Mi back to health…

Just as in dreams, time doesn’t necessarily obey the rules of reality here. When he does recover, we see his happy life unfold, the life that was spared by the Snow-Maiden’s mercy. He meets pretty orphan girl Oyuki (Keiko Kishi), and after a happy courtship of frolicking through sunset fields, they get married and have a fine family with two sons and a daughter. As the years montage by, he seems to lead a charmed life… until one evening, he’s reminded of the strange spirit that spared his life and the promise he made…

This section veers further from horror film expectations than the first and pushes the use of experimental imagery with expressionistic backdrops and painted skies filled with prying eyes. It’s both breathtakingly beautiful and unnerving and of all the film’s chapters revels in its artifice the most.

It probably owes a debt to the luscious Technicolor imagery of Powell and Pressburger’s Tales of Hoffman (1951), a particularly lavish stage production that used its contrived sets to evoke an unreal atmosphere. (Another film I know from seeing stills and have never watched, this time out of choice because it’s an adaptation of the Offenbach opera, not the original fairy stories!)

I was also reminded very much of Count Dracula’s eyes watching from a fiery sky over what was unashamedly a set in Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992). Kwaidan was a huge influence for Francis Ford Coppola and partly why he hired Japanese fashion designer Eiko Ishioka. Her costumes, which the director said would “be the set”, picked-up a few accents from Masahiro Katô’s meticulous designs for Kwaidan, which were also coordinated with the narrative use of colours in the sets and lighting in much the same way…

Kwaidan’s use of colour runs far deeper than the purely aesthetic. Using colour as a central storytelling element was one of Masaki Kobayashi driving intentions right from the start. At a time when monochrome was still favoured for serious horror films, such as Jack Clayton’s The Innocents (1961) and Robert Wise’s contemporary ghost story The Haunting (1963), Kobayashi wanted his first colour production to introduce it as an integral element of visual language. To this end, he decided to shoot nearly all the film on lavish sets in a studio so he could control every aspect of colour and lighting and meticulous design every inch of the mise-en-scène.

Though he eventually achieved his quest, the film bankrupted him and the studio! The production exceeded its budget to become, at the time, the most expensive Japanese film ever made. After scouting the length and breadth of Japan for locations, he began filming but was unhappy with having to rely on real places and the weather, bemoaning the lack of control over colour and lighting.

So, he decided to build a world from scratch. Trouble was, there were no studios big enough to house his planned sets, so he hired an aircraft hanger instead. The entire set for all four segments was built as a huge diorama, including water tanks for the sequences involving lakes, rivers and sea-battles. It must’ve been like building Thra for The Dark Crystal (1982)!

Instead of using matte-painting to make the sets seem even bigger, he chose to have fully-painted backdrops produced, the designs of which provide some of the most unique imagery in the film, such as the surrealistic ‘eyes-of-the-skies’ seen in the second chapter and often the sky foreshadows supernatural events with an infernal red.

The use of colour throughout is nothing short of stunning and must be applauded. The empathic, changing hues of the lighting, which aren’t shy of using some fully saturated primary colours are reminiscent of the films of Mario Bava and Roger Corman, but those western directors were only just starting to express their distinctive styles with colour around the same time. Bava was pioneering his expressive colours in Black Sabbath (1963) and Blood and Black Lace (1964). And Corman’s similarly stylistic Masque of the Red Death (1964) was also made the same year.

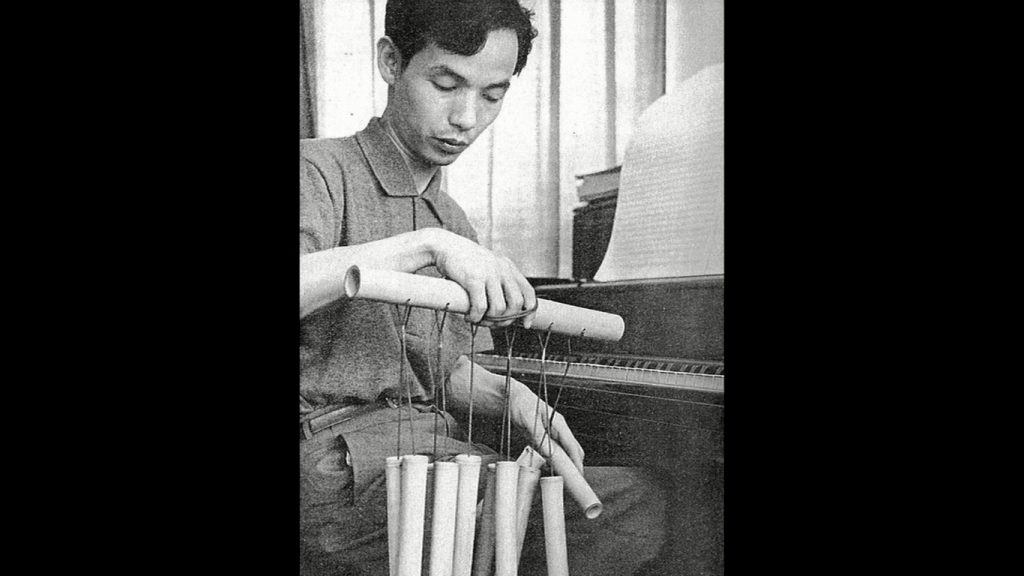

It’s not just the visuals that contribute to the immersive atmosphere of the film. Kobayashi once again hired Tôru Takemitsu, who had composed the score for his award-winning Harakiri / Seppuku, and brought him in early in the production process. He wasn’t just asked to compose music, but to oversee the whole sound-design. This enabled him to use natural sounds as part of the composition, sometimes morphing wind and music into one another.

One innovation he brought to the finished film was the odd disassociation of sound and image. Many of the scenes, particularly in the opening story of the anthology, lack diegetic sound and play out in silence. Selected sounds are then reintroduced, but with plenty of reverb, giving them a dreamy otherworldly effect. The noises are also delayed, so we see something happen in strange silence and then, a few seconds later, are disconcerted further by the oddly amplified sound. An effectively discombobulating innovation.

As in the first segment, the central cast of Yuki-Onna is small. Tatsuya Nakadai is excellent in the lead as the handsome young woodcutter. He plays the part lightly with an endearing innocence and charm. It took a while for me to remember he starred in the Sword of Doom as the chillingly unmoved samurai who degenerates into a psychopathically crazed killer with a death wish. The two roles couldn’t be more different! No wonder Nakadai was Kobayashi’s favourite actor, also starring in The Human Condition.

This is perhaps the most beautiful, poetic, and poignant segment of the film. It doesn’t really fit with the horror genre, despite its vampiric themes, and is more of a fairy tale. There’s no real villain here and the supernatural entity is a very sympathetic one. The tragedy-tinged ending is delicate, beautiful and haunting.

Considering the film’s split into four distinctly different sections, it works really well as a whole, and it would be hard to choose a favourite story… but if I was pushed, Yuki-Onna: The Snow Woman may be mine. Which is why it’s such a shame that this chapter was excised entirely for general distribution outside Japan! The tale was jettisoned mainly to cut down the duration which distributors thought would deter most cinemagoers. Admittedly, it’s a long film. At nearly 90-minutes, the first two stories together are already feature-length when we reach ‘half-way’, marked by an intermission.

Intermissions were the norm in the heyday of classic cinema, giving audiences a chance to stretch their legs, have a comfort break and buy ice cream and cigarettes from the concessions kiosk. But hey, now in the age of Blu-ray and streaming, we don’t need to be daunted by durations and if Kwaindan sounds too long, simply approach it as a four-part miniseries. You’re welcome.

This is the longest and most epic of the four sections and is really two stories combined, about a balladeer who sings an epic poem which we experience as a nested narrative. Of all the segments, this works best as a satisfying standalone episode and was, indeed, released as a separate film in its own right.

It opens with the confidence of an epic as the camera tracks across details from classical screen paintings, presented almost as a graphic novel, while we listen to a stirring song commemorating the historic sea battle of Dan-no-ura, pitched in the Shimonoseki Strait during the 12th-century Genpei War. The battle ended with the definitive defeat of the Heike Taira clan at the hands of the Genji Minamoto clan, the tragic death of the six-year-old Taira Emperor and the mass suicide of his entire entourage who refused the dishonour of surrender.

The battle is also staged as luscious live-action using one of the huge specially constructed water tanks in the studio, with plenty of smoke and dry-ice lending atmosphere and the illusion of motion to the boats. The combination of the song, its lyrics (explained with simplified subtitles), the intense visuals and some excellent, restrained acting from the silent cast really works together. It takes a great deal for a film to affect me on a deeper emotional level, but the sequence where a series of people plunge to their deaths into the blood-red water was unexpectedly effective and certainly brought a tear to the eye.

The young novice monk Hōichi (Katsuo Nakamura) is a new recruit at a coastal Buddhist monastery near to the stretch of sea where the battle occurred. He hears the monks speak of the restless spirits of the Taira clan who haunt the waves and are blamed for sinking fishing boats on still waters.

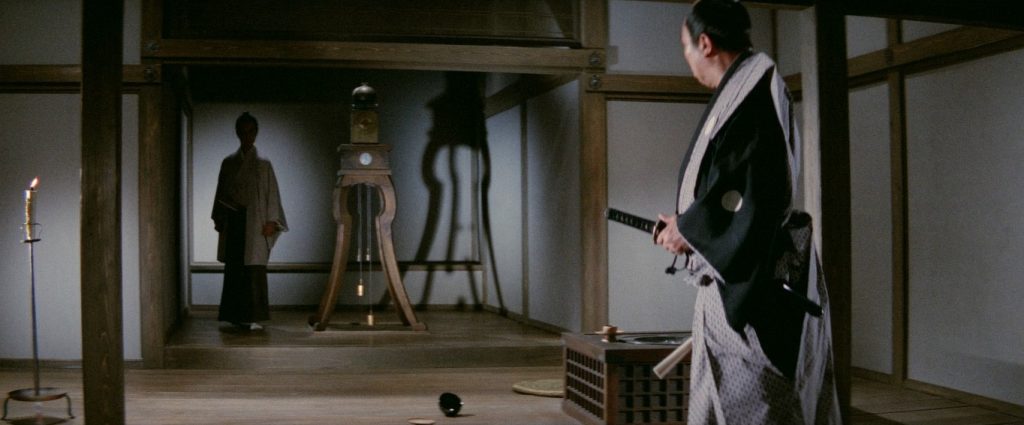

At night, when Hōichi is left alone to watch over the temple, he practices playing his biwa, a sort of lute that folklore tells us can be heard by the spirits of the ancestors. One night, he’s visited by a samurai, attracted by the beauty of his playing, who asks Hōichi to perform for his master, the lord of a great clan.

Being a humble monk, Hōichi is honoured to be asked and accompanies the samurai to a great castle. Here’s where the film plays a clever game with its audience. You see, Hōichi is blind, so doesn’t see what we see.

He’s taken to what appears to be a ruin and performs for what are clearly ghosts—their white faces and the broken arrows that protrude from some of them would’ve been a dead give-away. Plus, we can recognise the child emperor and several of the characters from the opening battle reconstruction.

They swear him to secrecy and request that he play the magical biwa and sing the epic poem about the battle of Dan-no-ura, which has so many stanzas that it will take several nights to recite. He complies gladly and without judgement. The haunting quality of his voice was achieved by dubbing in a woman’s voice and electronically lowering the pitch, more of Tôru Takemitsu’s trickery, I presume.

Hōichi returns, night after night, to continue the saga. As he does, and their story is told, we see the castle become more solid and return to its former glory. The life seems to be returning to the departed spirits also as they are remembered, and their story is retold. A metaphor of bringing history to life!

The other novice monks notice that Hōichi goes missing at night and presume he visits a secret lady friend, which would break their vow of celibacy, so to begin with they cover for his absence. When he becomes weak and deathly pale, they bring it to the attention of the head priest (Takashi Shimura). He’s quick on the uptake and has Hōichi followed to the nearby graveyard of the Taira clan where he starts playing his biwa before an audience of will-o’-the-wisps.

Hōichi is dragged back to the monastery, from what he believes to be a resplendent royal abode, and the kindly head priest explains that if he continues to pass across to the place of spirits, there will soon come a time when he will die and remain there forevermore.

To prevent this from happening, the monks write the protective Heart Sutra spell over every inch of his body. This will render him invisible to the spirits and the hold they have over him will be broken. All he has to do is sit perfectly still when the ghost samurai comes to collect him. However–-and this may be considered a spoiler, so skip to the next paragraph if you want to avoid it—the monks neglect to write the spell on his ears. Well, the clue’s in the segment title!

Yes! The iconic image that so impressed all those many years ago is from this quite gruelling sequence. It’s such a weird and strikingly effective image that it has been quoted across different media ever since. John Milius cites it as the direct source for the idea of painting magical camouflage on Conan to render him invisible to ghosts during his ‘resurrection’ sequence in Conan The Barbarian (1981).

It clearly influenced the painting of sigils onto the faces of the possessed in the 2006 Doctor Who two-part story “The Impossible Planet” / “The Satan Pit”. It also inspired artist Zhang Huan’s 2000 performance, Family Tree, in which he had the names and stories of his known ancestors written on his face, adding associated stories and his own thoughts until his face was entirely obscured with the black ink.

The concluding chapter is an oddity and another nested narrative with a wrap-around story that a caption tells us starts in, “Year 32 of the Meigi Era”. It’s New Year, 1900, and a writer (Osamu Takizawa) is at work with his brush-pen among his piles of books.

Just like all the interiors of Kwaidan, the shots are beautifully composed. Set-dresser Dai Arakawa’s attention to period detail is admirable. Even when there are no actors on screen, the empty sets can be enjoyed in much the same way as the famous woodblock prints of the Ukiyo-e era, which were a touchstone for art director Shigemasa Toda, who’d already worked with Kobayashi on his international breakthrough movie, Harakiri / Seppuku.

The empty author’s studio could well be modelled after a classic Japanese print. Hang on, empty? Where did the writer go? He seems to have vanished and when his publisher (Ganjirô Nakamura) arrives bearing a New year’s gift, he’s nowhere to be found…

The publisher leafs through the unfinished story on the abandoned desk and we are also absorbed by it with another caption that sets the scene as, “220 Years Ago, New Year’s Day in the 4th Year of the Tenna Era”.

After the darkness of Hōichi’s tale, the brightly lit exterior is refreshing, indeed Kannai (Kanemon Nakamura), one of the guards on parade outside a well-to-do mansion, breaks rank to get himself a refreshing cup of tea. As he lifts the cup to his lips, he hesitates because the face he sees reflected in the liquid is not his own!

Freaky, huh? He’s a middle-aged chap and the face he sees is a young man, decidedly handsome in an androgynous sort of way. He discards the tea and pours himself another cup, but the same thing happens again, this time the face in the tea gives a defiant grin that Kannai takes as a challenge and downs the tea in one to demonstrate that he can’t be intimidated. Oh, but y’know, he can be…

Later, whilst guarding the mansion that night, an intruder appears and introduces himself as Shikibu Heinai (Noboru Nakaya). Kannai recognises him as the face from the tea and lunges at him with his katana. The ghostly spirit doesn’t fight back and, instead, leaves no trace as he exits through a wall. Over the following few nights, Kannie is beleaguered by visitations by other spirits and quickly sinks into madness…

The final sequence is the shortest and leaves us in a state of puzzlement, as the narrator tells us…

Some of the old tales of Japan have come down to us in curiously unfinished form. Why were they left unfinished? Perhaps the writer was lazy. Perhaps they had a quarrel with their publisher. Perhaps he was suddenly called away from his little desk and never returned… perhaps death stopped his writing-brush in the middle of a sentence.

The final scenes are just as tongue-in-cheek as they are strange and chilling and will, no doubt, spark existential discussions about their meaning. After all, we are all stories, and our tales are always unfinished

Kwaidan is an astounding cinematic achievement, belatedly one of my favourite films and certainly one of the most beautiful. Its influence can be seen resounding through many classic films since: from the mad samurai and shoguns in Akira Kurasawa films (often played by the great Tatsuya Nakadai), through the expressive colour in the early horror films of Roger Corman and Mario Bava and the all-out saturation of Dario Argento classics Suspiria (1977) and Inferno (1980), to the recent J-Horror revival with their unnerving imagery of the dead and girls with long black hair. There are even influences felt in the oriental vibe of Copolla’s take on Dracula and the lavish costumes in Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace (1999)—even Darth Maul’s look owes a lot to Hōichi!

For a comparatively obscure film outside of Japan, Kwaidan has certainly left its indelible mark on cinema and still offers a hugely rewarding viewing experience…

JAPAN | 1964 | 183 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

director: Masaki Kobayashi.

writers: Yoko Mizuki (based on ‘Stories and Studies of Strange Things’ by Lafcadio Hearn).

starring: Rentarō Mikuni, Keiko Kishi, Kazuo Nakamura & Kanemon Nakamura.