THE SPECIALISTS (1969)

A gunfighter contends with a pacifist sheriff, a seductive banker, a one-armed Mexican bandit, corrupt businessmen, and hippies, while trying to learn the secret of the money allegedly stolen by his lynched brother.

A gunfighter contends with a pacifist sheriff, a seductive banker, a one-armed Mexican bandit, corrupt businessmen, and hippies, while trying to learn the secret of the money allegedly stolen by his lynched brother.

The Specialists delivers everything one could want from a Euro-western… plus a few things one might not! There’s no denying writer-director Sergio Corbucci is trying to keep things interesting in what was a late-entry into an over-worked genre. This is the final addition to his loosely related ‘Mud and Blood Trilogy’ that began with Django (1966), perhaps his best-known movie after the recent Quentin Tarantino reboot, and then The Great Silence (1968), considered by many to be his finest film.

The Specialists follows the successful template set out by another Sergio—Leone—in his ‘Dollar Trilogy’, beginning with A Fistful of Dollars (1964), coupled with Duccio Tessari’s first Ringo film, A Pistol for Ringo (1965). We have all the familiar characters and scenarios: the stoic drifter of few words, the larger-than-life Mexican bandit, the frontier town with its ineffectual lawman, corrupt bourgeois citizens, their henchmen, a young woman in jeopardy, and assorted saloon girls. Boxes all ticked!

Corbucci was a highly capable, jobbing director who found plenty of work in the prolific Italian film industry of the 1960s and ’70s. He’d already directed more than 30 films and would go on to direct 30 more during a career spanning four decades. So, as expected, he handles the formula with aplomb. What sets The Specialists apart from many other Euro-westerns is how he seems to have thrown all the ingredients into a shaker and mixed them into a satisfying cocktail, but with an overtly political theme floating on top as the garnish.

The script went through several stages of evolution, beginning as a collaborative project between Sergio Corbucci and Lee van Cleef, who co-wrote a script with the working title, Il Ritorno del Mercenario / Return of the Mercenary. Unfortunately, that project never came to anything and Corbucci, this time in collaboration with writer Sabatino Ciuffini, later repurposed some of the ideas for The Specialists, including the main character, who habitually wears a chainmail waistcoat, returning to solve a crime that had been perpetrated in his absence…

The film opens with Mexican bandits robbing a stagecoach as it waits at a relay station. The well-to-do passengers are laying down in the dirt whilst the bandits have their sport with a group of four youngsters. Much has been made of the incongruous hippy styles of the youth but that reference, whilst certainly intentional, isn’t made clear until much later. Sure, they do look like a bit like the contemporary 1960s hippies, but their apparel (an army jacket adorned with tarnished medals, poncho, scarves and headbands) isn’t anachronistic for a Wild West setting.

However, the first hint of the political subtext is literally thrown-in right at the start when one of the desperadoes tosses a silver dollar into a muddy pool. He gleefully tells the youngsters that the one that retrieves it will be allowed to live, instantly turning friends against one another in a heavy-handed metaphor of capitalism.

One of the bandits ventures into the station in search of supplies to steal. On discovering a barrel of liquor, he selfishly decides to down as much as possible himself before sharing any with his compadres outside. As he raises the barrel to drink, our ‘man-with-no-name’ (Johnny Hallyday), who wears a distinctive chainmail waistcoat instead of a poncho, emerges from the shadows like a ghost.

After the staccato shootout that leaves the bandits either dead or running for their lives, we immediately learn that he does indeed have a name—“Hud! The great Hud!” cries the cowardly gambler, Cabot (Gino Pernice), one of the stagecoach passengers. He wants to befriend Hud and have him escort them as protection. The youngsters, rescued from their mud-bath of doom, are impressed and want to travel with Hud and learn to shoot like that.

The tall, handsome Hud tells them that he has no friends and they are left to watch as he rides off alone. It’s like a remake of Shane (1953) compressed into the pre-title sequence! You can have fun looking for other references to classic westerns throughout the rest of the film—like the glimpse of a clock showing a quarter-to-noon in the build-up to a decisive showdown…

Corbucci knows what needs to be done and wastes no time in getting down to business! We’re not even 15-minutes in when all the basic plot setup is done and all the main players have been introduced. We meet the movers and shakers of the town of Blackstone in a single scene as they bicker about which of them was the most instrumental in the lynching of one Charles Dixon.

They argue about who’s going to be their scapegoat when the victim’s brother finally comes to town. It seems it’s Hud’s brother who got the blame for a recent bank robbery that’s left them all financially unstable. In their fury, they ended up killing Charles before he could tell them where the money had been hidden. Now, a few of them want to see if Hud can figure out where his brother might have hidden the money, others are so terrified of retribution they simply want him dead ASAP.

Clearly, Blackstone was Hud’s hometown but he’s been away, presumably working as a mercenary in the revolution. The central mystery of what happened to the money drives the plot and motivates the key players as Hud tries solving the crime that happened in his absence. He’s pretty sure his brother was framed for the crime to cover-up a larger conspiracy.

There’s a sort of detective thread woven through the narrative that involves clues and deciphering the code of an ingenious secret map. It’s not a difficult case to crack, but there’s more than a few twists, turns, and double bluffs to keep it interesting. It certainly doesn’t take a Sherlock to work out who the villains are and anyone paying attention will be well ahead of the final reveal. And, if that reveal seems to come a little too early, don’t worry… as Corbucci has held back a final act with a few more surprises in store, and a climax involving one brave man standing alone against insurmountable odds to protect a few good people among the corrupt and cowardly citizens.

It’s another obvious homage to the final scenes of High Noon (1952) but taken up a few notches! I thought it was fun and hugely effective, but some have criticised the ending for being OTT or ‘out-of-place’. Perhaps they have a point. The mix of mass nudity, philosophy, political commentary and satire seems more like a prototype for El Top (1970), Alejandro Jodorowsky’s infamous ‘acid Western’, but without spoiling things too much I can say no more. Except that it concludes with what must be the best ever shot of a hero riding off into the sunset!

The Specialists is a three-nation co-production. Filmed in Italy, it makes great use of the dramatic Dolomite Mountains as its location plus the existent wild west sets at the famous Elios studios in Rome, the epicentre of ‘Filone’—the Italian Pulp Cinema Industry. By the mid-1960s the Italian film industry had become a well-oiled machine almost entirely fuelled by the drive to exploit genres. In many ways, it was a film factory like the post-war Hollywood studio system, or perhaps Hammer films at Elstree in the UK.

In 1969, The Specialists was just one of around 30 ‘Spaghetti Westerns’ to be released and the appetite for that genre, whet by the international success of A Fistful of Dollars (1964), was already on the wane. The next big ‘Filone’ would be Poliziottesch— gritty crime thrillers inspired by the German Krimi genre.

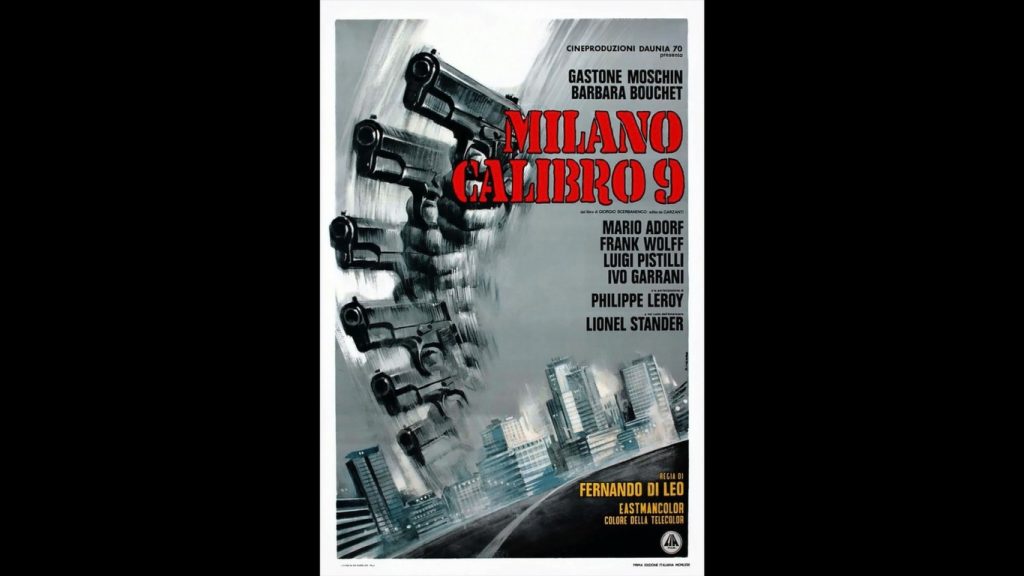

This ‘cross-pollination’ is already evident in The Specialists, part-funded by German production company Neue Münchener Lichtspielkunst GmbH (a.k.a Neue Emelka)—not to be confused with the much larger Münchener Lichtspielkunst AG, favoured by the likes of Alfred Hitchcock and Stanley Kubrik (which was then known as Bavaria Film Studios). Several cast members were reunited in Poliziotteschi movies, as Gastone Moschin and Mario Adorf would again star together in Fernando Di Leo’s Milano Calibro 9 (1972).

The third country involved in producing The Specialists was France, and their money came with a condition that there would be the prominent casting of French talent. It’s the first noteworthy entry into the modest filmography of the French rock star Johnny Hallyday, who was already used to being in front of a camera, though usually performing as a singer or, more or less, playing himself.

He’s fine in the lead role of Hud, though he doesn’t get a lot to do that shows off any real range. He’s great at looking moodily up from under the brim of his hat using his piercing blue eyes to full effect. He does a good job of smoking a cheroot in the style of Clint Eastwood and delivering minimal dialogue. His stillness in some scenes speaks volumes, but his main strength lies in his physical presence and he’s tasty in a brawl, owing a lot to the fight choreographer and tight editing, of course. He also has a distinctive way of riding a horse with one hand holding the reign, the other hovering near his holster as he sways in a sort of saddle dance.

It was the second film for Parisienne starlet Sylvie Fennec, who never really made it as an international star, and perhaps she didn’t want to because she remained busy both in front of and behind the camera as an actress taking varied roles, mainly in TV, and more often as a production designer. Here she plays the young ‘maiden in jeopardy’ Sheba with a winning combination of feisty and vulnerable. Sheba is the main love interest for Hud, though she does accidentally shoot him when trying to murder her abusive ‘father’, Boot (French actor Serge Marquand). It’s not the only time that Hud’s glad he wore his chainmail waistcoat.

The other female lead is taken by Françoise Fabian, who not long before had appeared in her first prominent international role as Charlotte in Luis Buñuel’s Belle de Jour (1967). She’s perfectly cast as the scheming, manipulative banker of Blackstone, Virginia Pollicut—a fading beauty who’d been Hud’s childhood sweetheart. Perhaps she still holds a grudge against him for not succumbing to her charms as they grew up.

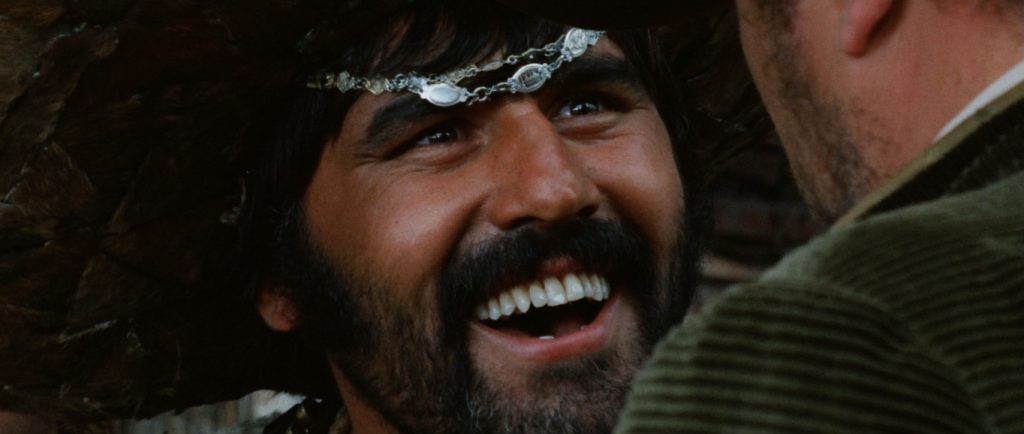

Another childhood pal of Hud’s is El Diablo (Mario Adorf), literally a one-armed bandit with a sharpened spur in place of his right hand. He’s the only representative of German casting here, but he certainly relishes his screen time. He’s exactly the kind of Mexican revolutionary we expect to see in a Euro-western, greasy, bestubbled and wearing a really massive sombrero. (Though I’m sure his teeth are far too bright and even to be historically accurate!)

El Diablo’s an ambiguous character who has a young scribe at his side at all times to record his trials, tribulations and triumphs. This is one aspect of a major discourse that runs through the narrative: the comparative value of actions over words. Even more relevant nowadays, with the proliferation of ‘false news’ in the age of the emotively misleading social media soundbite.

The lead Italian player is Gastone Moschin as the principled but ineffective Sheriff Gedeon, who we first see returning to Blackstone carrying his fishing rod and with a posy of flowers in the barrel of his rifle. Now, this was at the height of ‘flower power’ and that visual motif would’ve been fresh in the minds of audiences.

When an orchestrated peace demonstration had approached the Pentagon in 1967 to protest the Vietnam War, they were halted by armed military police. It was a volatile and potentially lethal situation which was diffused when a young man, holding a bunch of flowers, approached the soldiers and placed a single carnation into the barrels of each gun that were poised and ready to fire. The photograph was originally published in The Washington Star and later nominated for the Pulitzer Prize.

The primary subtext of The Specialists is a condemnation of the economic systems that drive global warfare and the hijacking of the peace-movement by what Corbucci thought of as social parasites, the so-called hippies. That’s quite a complex concept to explore within the format of an entertaining Euro-western!

The gang of four young peasants we met scrabbling for a silver dollar in the mud are, indeed, intended to be stand-ins for contemporary hippies. This is made clear in an odd scene when the sheriff argues with them over ownership of a fish he’s caught. Basically, the youths use the hippy cry of freedom to lay claim to said fish and argue that the sheriff is oppressing them. They claim he and his kind are responsible for their poverty when, actually, all they want to do steal the thing he had spent time and effort in obtaining. They want something for nothing. Their antics escalate and by the finale, they’re the main threat to Hud and the people of Blackstone…

Both Corbucci and Hallyday, though espousing libertine left-wing views, had been openly critical of the rising hippy movement, Corbucci saw them as a sort of cult that identified through mutual resentment and that, separated from societal norms, could be easily perverted into lawlessness. This did prove to be prophetic as the Manson Family murders of at least eight people, including the actress Sharon Tate, also took place in 1969 as production wrapped for The Specialists.

Sheriff Gedeon is a sort of pacifist who’s outlawed guns in Blackstone. This could well be a nod to the first cinematic sheriff famous for denouncing guns, Tom Destry (James Stewart) in Destry Rides Again (1939). It also serves to make things a bit more interesting and ensures that Hud’s without a pistol for some of the film, putting him a similar situation of Ringo (Giuliano Gemma) in A Pistol for Ringo. Thus, setting the scene for a rather intense fight when the unarmed Hud must take on several knife-wielding assailants in the Saloon. It’s a pretty brutal scene ending with an inventive ‘death-by-cash-register’—another dig at capitalistic greed, I presume.

The Specialists remains a superior example of the Spaghetti Western. It has everything the genre demands in terms of story and style. There are good guys and great bad guys, buxom bar girls, burly bandits, bumbling bureaucrats, and bent bankers. There’s liberal use of framing that sets tiny figures against sublime landscapes, juxtaposed with tight close-ups and dramatic zooms instead of cuts.

The inventive action sequences are consummately planned and executed—lookout for the sudden shootout that leaves the bad guy hanging by his ankle from the church bell rope, ringing a death-knoll for the town. The central plot is concerned with a figure from the past on a quest for just vengeance and could well have prototyped Clint Eastwood’s later attempt to reinvent the genre with High Plains Drifter (1973).

The Specialists was given Italian release in 1969 where it did middling business at the domestic box office. Likewise, its performance in France and Germany the following year was nothing special and it failed to get much attention from other territories until a trimmed and dubbed English-language cut was given UK distribution in 1973. Unfortunately, the English translation muddied the motivations of some of the key players, making the plot a little more confusing and the denouement less satisfying.

That’s why it’s great that it’s been given the respect it deserves with this 4K restoration of the Director’s Cut, presented on Blu-ray from Eureka Entertainment. It’s an opportunity for first-time viewers to discover, and for fans to revisit. I’m fairly sure that any aficionados of Euro-westerns will find much to enjoy and won’t be disappointed.

ITALY • FRANCE • WEST GERMANY | 1969 | 104 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | ITALIAN • FRENCH

director: Sergio Corbucci.

writer: Sergio Corbucci & Sabatino Ciuffini.

starring: Johnny Hallyday, Gastone Moschin, Françoise Fabian, Sylvie Fennec, Serge Marquand, Angela Luce & Mario Adorf.