MAD MAX (1979)

In a self-destructing world, a vengeful Australian policeman sets out to stop a violent motorcycle gang.

In a self-destructing world, a vengeful Australian policeman sets out to stop a violent motorcycle gang.

In H.G Wells’ acclaimed 1895 novella The Time Machine, a man known only as the Time Traveller is struck by sudden, intense fear before stepping out into the future world that awaits him. He ponders: “What might appear when that hazy curtain was altogether drawn? What might not have happened to men? What if cruelty had grown into a common passion? What if in this interval the race had lost its manliness, and had developed into something inhuman, unsympathetic, and overwhelmingly powerful?”

Director George Miller must have taken a line out of Wells’ book. In the not-too-distant future, the world of Mad Max has become a dangerous, lawless place. Crime is rife, almost as common as psychopathy, and there are too few police officers to enforce order. Rampant violence ensues, mostly at the hands of a rogue biker gang who seem intent on destroying society. As police officers resign or die, only Max Rockatansky (Mel Gibson) can bring civilisation back from the brink. But at what cost?

Mad Max is a challenging piece to assess today. It’s an action film without much action, an origin story where our eponymous hero often becomes a peripheral character. However, Mad Max became a cult classic for a good reason: the film’s greatest strength lies in its harrowingly realistic depiction of a society that’s fallen into irreparable disrepair, a civilisation crawling out of the rubble of an apocalypse. As ecocide has rendered life almost impossible, Miller’s film starkly imagines a world devoid of hope.

Our introductory credits are rather fitting for the film: namely, they seem quite confused, as though it doesn’t know what kind of movie it’s going to be. This shows throughout the progression of the story; it seems as if the hero is going to become a rogue avenger, but he’s often side-lined for other less interesting plot points. Despite his introduction as a calculated enforcer of the law, he’s characterized by his inaction for the first stretch of the film: given his moniker, Mad Max is surprisingly, even disappointingly calm.

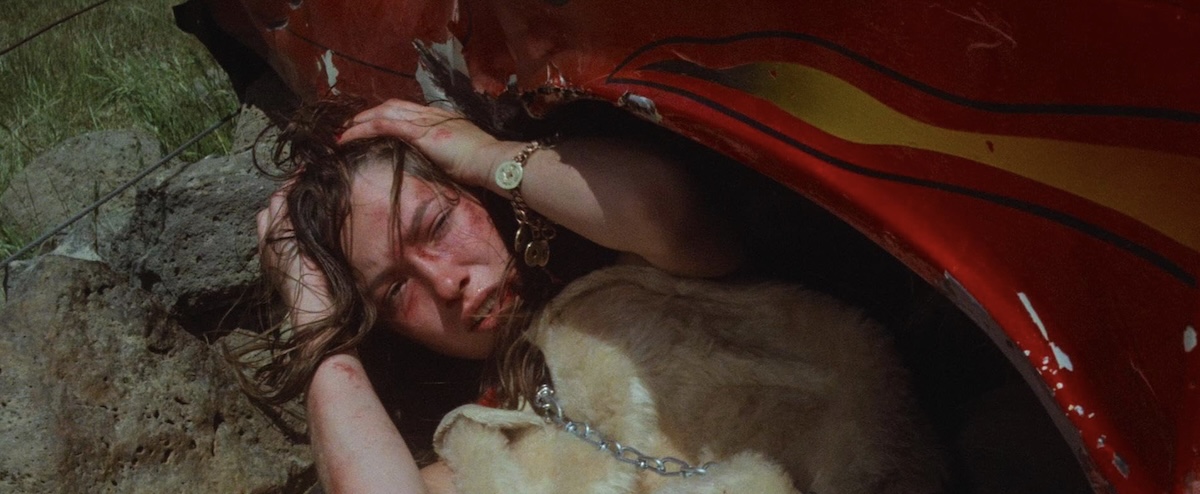

Of course, you probably won’t notice it in the opening chase sequence, which is arguably the action highlight of the whole film. The high-octane, catastrophic car chase utilises intelligent cinematography and real stunts to jolt the viewer into the reality of the new world order. As Max divulges, the Night Rider, who causes havoc for the police department and wreaks plenty of destruction, is merely one of many: “Just another glory rider, I guess.”

In this, we can see that Miller paints a picture of a failed state—an apocalyptic wasteland. The lack of bureaucracy or social order has much in common with the society conceived by Thomas Hobbes if humanity were to descend into a state of nature. By this, the English philosopher described how humanity would function without a governing body to create and uphold laws: utter chaos.

In a state of nature, life could only be lived for oneself; scarcity would force intense competition and disincentivise compassion and cooperation. Much like H.G Wells’ fear, humankind would evolve (or devolve) into an unsympathetic being, with cruelty becoming a common tendency. If freedom were not restricted by social institutions, anarchy could be the only logical consequence.

In 1651’s Leviathan, Hobbes wrote: “During the time men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that condition which is called war; and such a war as is of every man against every man.” In a state of this design, every person is guided by the necessity of doing whatever they can for self-preservation, meaning that life would not only be tough, but also “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” This bears a strong resemblance to Miller’s depiction of Australia.

Screenwriter James McCausland might not have drawn from Hobbesian philosophy; according to him, he didn’t have to look that far to imagine an uncivil society dominated by scarcity. In 1973, an oil crisis in Australia caused drivers to behave frantically, erupting into febrile violence if their attempt at obtaining fuel was kerbed. McCausland went on to say: “There were further signs of the desperate measures individuals would take to ensure mobility. A couple of oil strikes that hit many pumps revealed the ferocity with which Australians would defend their right to fill a tank. Long queues formed at the stations with petrol and anyone who tried to sneak ahead in the queue met raw violence.”

In a world dominated by a need or expectation for increasingly faster means of travel, the sudden threat of immobility terrifies us. This also provided fertile ground for examining our environmental myopia. In this respect, McCausland also revealed that: “George and I wrote the script based on the thesis that people would do almost anything to keep vehicles moving, and the assumption that nations would not consider the huge costs of providing infrastructure for alternative energy until it was too late.”

This was, unfortunately, all too accurate an assumption, proving ever more true over time. Recently, it’s been confirmed that the Austrian glaciers will vanish entirely within 50 years. In this regard, the theme of ecocide in Mad Max is arguably the film’s most powerful element. The narrative implies that government mismanagement caused the world’s demise, allowing hooligans to run amok unchecked.

However, rather paradoxically, the film simultaneously suggests that it’s only through a strong, assertive government that order can ever be established. The police portraying themselves as the arbiters of all that is good in the world is a message that lends itself to fascism, something that audiences will be more attuned to after the chilling, shocking events of 2020.

Max himself recognises his potential for becoming a sadistic thug on the road, protected only by the badge he wears. “Any longer out on that road and I’m one of them: a terminal crazy. Only I’ve got a Bronze Badge to say I’m one of the good guys.” Here, we can see how McCausland and Miller weave Nietzschean philosophy rather seamlessly into the narrative structure: “He who fights with monsters might take care lest he thereby become a monster. And if you gaze for long into an abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.”

Max’s acknowledgement that he too can slip into oblivion adds an interesting facet to his character, one that Miller regrettably neglects to explore fully. This is a shame because it would have provided a much-needed layer of theme and characterisation to the film. However, in this scene and the final rampage, Miller allows Nietzsche’s ideas to define Max’s character arc: “I’m beginning to enjoy it,” Max reveals.

This line elevates our protagonist to the level of a tragic hero, akin to those found in both cinema and literature, who become enamoured with the immense power they wield. The line also bears a striking resemblance to a passage of dialogue in David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia (1962). When T. E Lawrence (Peter O’Toole) confesses to executing a man, he remarks with a tremor of fear that something was unsettling about the experience: “I enjoyed it.”

Though Max might not be as well-developed as Lawrence, the outline of his character arc is present, demonstrating how good men can fall victim to the circumstances they live in. If nothing else, Mad Max showcases the trepidation one might experience when forced to confront their Jungian shadow: what would you be capable of if you were forced to live in such inhospitable environments?

The world Max inhabits is certainly that. Budget constraints prevent Miller from fully realising the apocalyptic aesthetic that would elevate and define the sequels. The meagre budget impacts the effects throughout the movie. Firstly, there’s a plethora of unconvincing costumes on display. The supposed hard-boiled, leather-clad cops are wearing vinyl costumes. Only Goose wears genuine leather, which he already owns due to being a motorcyclist. He also claims this is the sole reason he landed the role, implying it wasn’t down to his acting prowess.

The budgetary restraints are also evident in the stunts, some of which don’t make as much visual sense today. However, when we consider how they were filmed, it’s impossible not to be impressed by the crew’s sheer ingenuity. Not only did they film most of the car chases illegally—without police oversight or shooting permits—but they also shot each action scene just once, and quickly enough to avoid detection by the authorities. Unsurprisingly, this wasn’t always successful: Victoria Police eventually agreed to assist the production for the sake of public safety. A wise decision…

However, perhaps the most notable manifestation of the string budget can be found in the plot. Much like the world depicted, the story lacks direction. It’s also tonally inconsistent and it feels as if important plot elements are omitted, while others are inexplicably included. For example, we witness Goose seduce and sleep with an attractive singer, something entirely extraneous to the plot. However, we don’t see the court case where justice is miscarried, and no one attends, an opportunity for Miller to emphasise the theme of a failed state.

Having watched this as a child, I didn’t notice these strange plot choices then, but the inclusion and omission of certain scenes raise an eyebrow now. Perhaps most notably, Miller also doesn’t fully deliver on the film’s revenge theme. Max’s quest for vengeance lasts less than 15 minutes, which is sure to frustrate those who came for a tale of arid, desert-set revenge.

In this respect, the film is truly more of a tragedy than an action thriller. It dramatises both the internal devolution of man and the societal decay that caused it. This differs from some other contemporary revenge films, such as The Beekeeper (2024), which features no subtext or theme but devotes its entire runtime to gratuitous revenge. Personally, Mad Max is infinitely preferable: even if it falters in certain areas, it strives for sincerity.

Ultimately, the film’s narrative structure might not be the strongest. It also lacks well-developed characters, which weakens the impact of much of the melodrama. Indeed, one can even imagine that without Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) becoming such a mainstream success, George Miller’s original instalment would have faded into obscurity. It’s too sparse for an origin story—arguably, the entire plot could have unfolded within the first half an hour—and too slow-paced to be a bona fide action film.

However, what the film does possess is a surprisingly shocking portrayal of a failed state, alongside a brief depiction of the degradation of a man’s soul as a consequence of his broken civilisation. In the film’s iconic final shots, Max is almost asleep at the wheel, a man who’s become dead inside, a steely gaze within a tortured visage. He’s bereft of love, an utter ruin of a man, now utterly devoid of hope. And, perhaps most importantly, it is this complete absence of optimism and expectancy that has caused the social decay around him: he lives in a world without hope.

Though the film falters in several areas, both as an origin story and a high-octane thrill ride, it does succeed as a tragedy of sorts. Max becomes precisely what he swore he wouldn’t: a ruthless avenger on the dusty roads of a post-apocalyptic wasteland. While the sequels unquestionably improved upon the action sequences—and were arguably better films overall—they never captured the desolate reality of a shattered world quite as effectively.

AUSTRALIA | 1979 | 93 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: George Miller.

writers: James McCausland & George Miller (story by George Miller & Byron Kennedy).

starring: Mel Gibson, Joanne Samuel, Hugh Keays-Byrne, Steve Bisley, Tim Burns & Roger Ward.