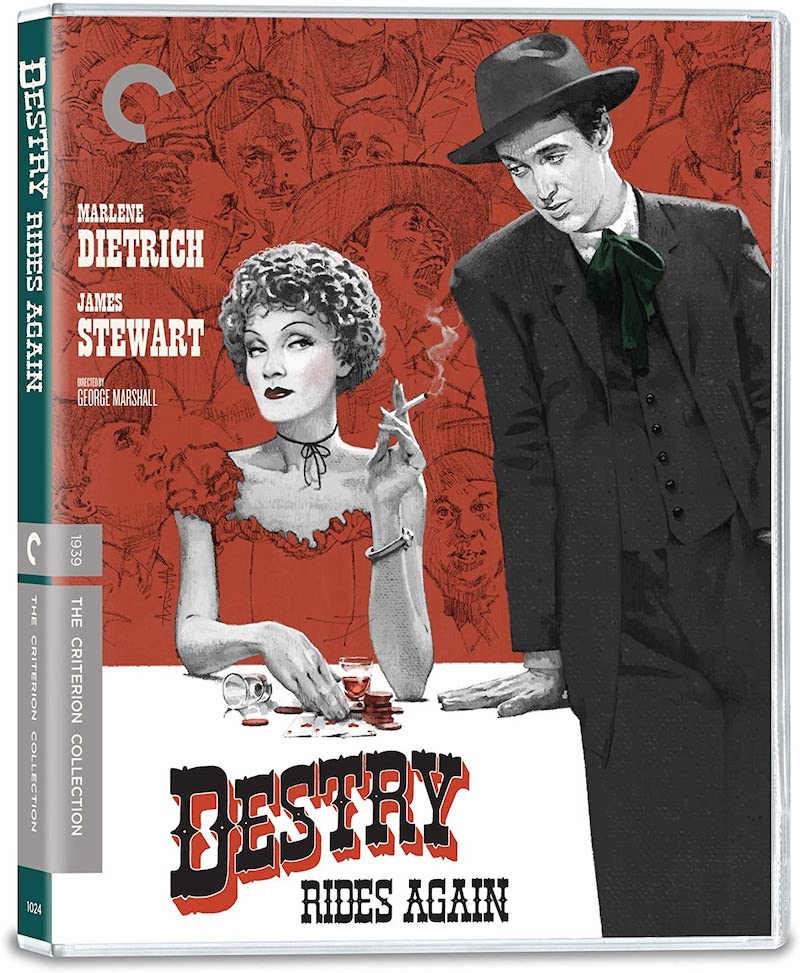

DESTRY RIDES AGAIN (1939)

When a tough western town needs taming, the mild-mannered son of a hard-nosed sheriff gets the job.

When a tough western town needs taming, the mild-mannered son of a hard-nosed sheriff gets the job.

There are many ways to enjoy Destry Rides Again. For a start, it’s a must-see for anyone who considers themselves a fan of Westerns, cited by some as the greatest comedy-western of all time. It’s a must-own for fans of James Stewart or Marlene Dietrich, being a pivotal part of both their careers. And it’s great fun for anyone who, like me, is a sucker for classic movie nostalgia. I remember watching it as a young ‘un, not in the cinemas (I’m not that old) but from Saturday matinee television reruns. They don’t make ’em like that anymore! And with good reason, some may say!

It may not impress a modern audience too much but, 80 years ago, this was a great movie that reinvigorated the tiring Western genre. The main weakness of Destry Rides Again is it’s very much of its time, but that’s precisely what keeps it interesting—at least to the niche audience who’ll welcome this absolutely gorgeous 4K digital restoration on Blu-ray, recently added to the Criterion Collection. It remains a fine example of what the interwar Hollywood studio system could produce at the height of its powers.

The title makes it sound like a sequel but it isn’t. It’s a remake. Though today we would probably call it a ‘reboot’ because it differs so much from the original 1932 movie, which was already far removed from the original 1930 novel of the same name by Max Brand.

Frederick Schiller Faust wrote under many noms-de-plume of which Max Brand was his most successful. Faust was best known as a prolific author of pulp Western stories but also created the character of Dr Kildare, as played by Lew Ayres in a nine-film series for MGM (1938-1942), and later made Richard Chamberlain a star in the NBC five-season TV series Dr Kildare (1961-66).

The 1932 film adaptation starred Tom Mix, one of the biggest stars of Hollywood’s silent age. Destry Rides Again was his first ‘talkie’, coming near the end of a movie career that began in 1909 and included more than 290 titles. Tom Mix was the real deal; a genuine cowboy who could ride, shoot and use a lasso. Wild West shows and rodeos had made him a celebrity before the age of cinema, and one of his first screen appearances was as the subject of a documentary.

The films of Tom Mix were instrumental in defining the Western as it emerged. They were action-driven and Mix wore a huge white hat and bravely took on very clearly defined bad guys who wore black hats, of course. When he took the part of Destry, the character’s first name was changed from ‘Harry’ to ‘Tom’ in his honour.

The film was a stripped-down version of the novel’s story, keeping only the central plot of a man, wrongly convicted of a crime, returning to exact vengeance upon the crooked jurors who put him away. Mix played the role as the typical hard-riding, sharp-shooting, fist-fighting masculine hero he’d led audiences to expect.

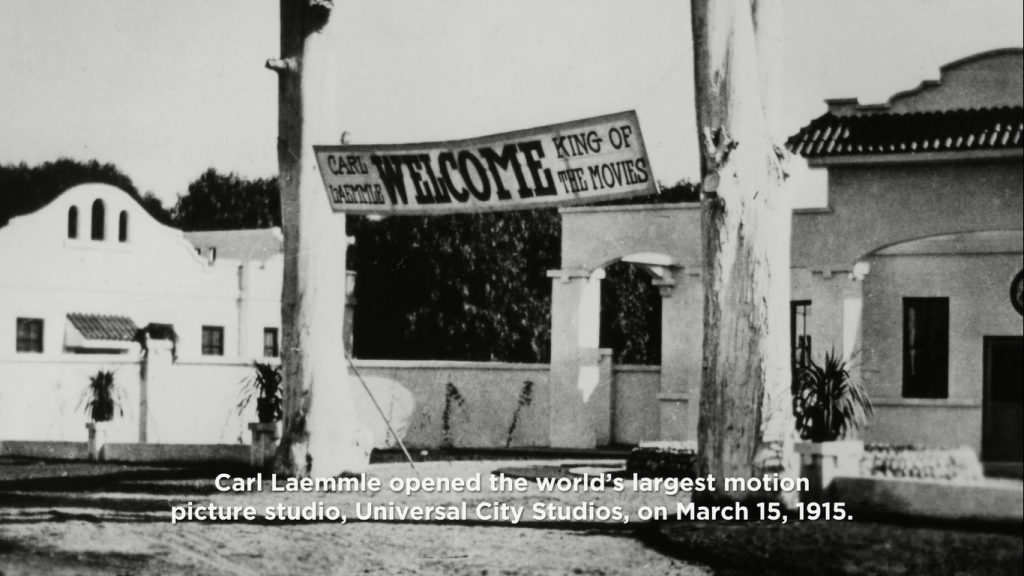

It had been made at Universal Studios, which was always looking to rework and update properties they already owned. Joe Pasternak, a contracted producer at Universal, saw the potential for Destry to ride again as a spoof of those old Westerns. He passed the existing script to Felix Jackson and, together, they finally came up with something that bore little resemblance to either the original novel or the earlier film. They took all the established iconography of the genre, including its clichés and stock characters, and combined them in surprising ways. There’s a little bit of everything thrown into the mix: comedy, tragedy, song and dance.

Pasternak found a suitable director in George Marshall, already a veteran of the Western, who’d even made several films starring Tom Mix in the 1920s. He’d also proven himself as a director of comedy with a handful of Laurel and Hardy films including a couple of shorts, Their First Mistake (1932) and Towed in a Hole (1932), and their second feature, Pack Up Your Troubles (1932), in which he also appeared.

Destry Rides Again opens with the sound of gunshots and cries of “yee-hah!” As the titles roll, the camera takes us on a leisurely stroll down the main street of Bottleneck and into the town’s smoky saloon. Immediately, one is struck by the high production values evident in the large two-level set, and the sheer weight of extras, all in period attire. And we’re straight in with a musical number as Frenchy (Merlene Dietrich) takes to the stage to sing a comic reinterpretation of the originally tragic cowboy folk song “Little Joe, the Wrangler.”

The standard lyrics have been rewritten by Frank Loesser, turning the sad ballad about the death of an orphan into the raucous singalong that tells of a happy-go-lucky ne’er-do-well. Yes, it’s a song about a different ‘Little Joe’, just like the film’s going to be about a different ‘Destry’… a not-so-subtle reference that may well be missed by viewers nowadays.

We’re also seeing a different Dietrich to the aloof femme fatale image she’d cultivated in her earlier roles for Josef von Sternberg. Apparently, she took the part for half her usual fee, hoping to showcase different aspects of her repertoire, after suffering several box office flops. The role proved to be her Hollywood comeback.

Dietrich is exuberant and brash and looks to be having a fine time. She even rolls her own cigarette at the bar, whilst singing and delivering ‘yee-hahs!’ that’ll set your teeth on edge. Fans of Dietrich will be delighted that this is but the first of three songs she’ll be singing during the film, all with up-beat lyrics by Loesser and melodies composed especially for her by Friedrich Hollaender, who had written the torchsong “Falling in Love Again”, which Deitrich first sang in German for her defining early role in The Blue Angel / Der Blaue Engel (1930). Destry delivers her career’s other best-known song, “See What the Boys in the Back Room Will Have”.

It wasn’t uncommon for films of that era to open with either a song or a fairly uneventful sequence, allowing plenty of time for the audience to find their seats and settle in. The extended musical opening here has lots going on and the roving camera introduces a few of the main players in a drawn-out and complex tracking shot. There’s some comedy drunkenness from the banjo player, Wash Dimsdale (Charles Winninger), his antics perhaps reflecting Marshall’s experience of physical comedy with Laurel and Hardy.

It’s not long till we do, indeed, find out what the boys in the backroom are up to. They’re playing crooked poker games that involve Frenchy acting as the distraction whilst they switch the victim’s cards. This time their mark is a simple settler, Lem Claggett (Tom Fadden), whom they proceed to swindle out of house and homestead. When the sheriff (Joe King) intervenes, we hear gunshots from the backroom shortly before the gambling gang’s ringleader, Kent (Brian Donlevy), emerges and pins the star onto Wash, making the barely coherent drunkard the new sheriff of Bottleneck. He’s duly sworn in, there and then, by the corrupt Judge Slade (Samuel S. Hinds).

Clearly, the town’s rotten to the core. What hope does some harmless old coot have of making any difference? It turns out that Wash was once the deputy to the legendary sheriff Destry, back when it was a crime-free, decent place to settle down. He sobers up and starts taking his new duties seriously, though no one in town takes him seriously at all. So, he sends for a new deputy, the son of Destry, warning the townsfolk to expect a no-nonsense tough guy, just like his famous father had been.

When Destry Jr (James Stewart) arrives, he makes a markedly different first impression as he disembarks the stagecoach holding a frilly parasol and a caged canary. This was not what they expected, and this is the film’s central goal—-to play with and confound audience expectations of the Western genre. There’re important points to be made, that looks can be deceiving and that a ‘real man’ doesn’t have to match the manly clichés, but Marshall tries not to let this serious theme get in the way of the laughs.

Casting the lead role had been problematic. It seems that most of the tough-guy actors associated with Westerns weren’t comfortable with showing their gentler sides. They thought it would be detrimental to their career and public personae. So, Pasternak and Marshall decided to take a different tack. Although he’d been ‘bubbling under’ for a while, James Stewart had only just come to wider attention in Frank Capra’s You Can’t Take It With You (1938), which won Academy Awards for ‘Best Film’ and ‘Best Director’.

James Stewart, they thought, would be perfect for Destry! But he wasn’t available. Capra had cast him again, this time in the leading role for Mr Smith Goes to Washington (1939), which would turn out to be his breakthrough role and earn the actor his first Oscar nomination. With no other names matched to the part, it looked like Destry might never ride again. So, the production was put on hold until Stewart was free… the best decision Universal could’ve made!

Gender stereotyping is challenged further in the famous bar brawl which became one of the more controversial scenes. It pushed a few censorship buttons because it twisted one of the tried and tested tropes of the Western by having two women, Frenchy and Lily Belle Callahan (Una Merkel), fight over a man. Cuts were avoided by adding some broad comedy and having the situation diffused by a well-timed bucket of water…

Much of the (over)acting from the rest of the cast seems to be a hangover from the silent era, with James Stewart’s naturalistic style standing out among a showcase of exaggerated mannerisms and comic caricatures. That said, they probably weren’t caricatures back then! The success of this film established them as such. Comedy drunks say things like “I’m plum tuckered out!” but isn’t that what we want from an old classic Western? But when Marlene Dietrich stuffs handfuls of coins down her bodice and says “there’s gold in them there hills” the censors got all hot n’ bothered and the line had to be cut for general release after its debut run in New York.

Brian Donlevy turns-in a good performance as the suave villain, Kent, hiding his cool, calculating amorality behind his winning smile. It took me a while to place his face because he’s much younger than when he played Prof. Bernard Quatermass in Quatermass Experiment (1955) and Quatermass 2 (1957)! But the success of Destry Rides Again, relies on its two central performances…

For me, Dietrich is never wholly convincing. She always seems to be acting! With her portrayal of Frenchy, she gets away with it because the character is putting on an act and pretending to be something she’s not. Destry sees through this and when she does finally allow us a glimpse beneath the veneer, it’s one of the few tragically affecting moments. There’s some on-screen chemistry between Stewart and Dietrich that adds a little frisson and reflected their passionate, though short-lived, off-screen affair.

Stewart is playing the type of character he’d become known and loved for. He’s likeable, charming, and good-natured. His range as Destry is formidable. One moment, he’s goofing around, telling tall stories with ridiculous punchlines. In the next scene he emanates a sense of underlying threat with his quiet, assured confidence. Sometimes he delivers his lines so softly they’re almost whispered, and we hang on every word.

When one of his friends is shot in the back, the camera stays on Stewart’s face in tight close-up. All sense of comedy evaporates, and he delivers an emotional sucker-punch. That’s how his father was murdered, too. Though he can’t be absolutely sure who actually pulled the trigger, on either occasion, he’s darn sure who created the situation that led to both deaths.

Although the entire film’s been leading up to it, and it’s the key moment of narrative reversal we’ve been waiting for, the climax fails to pay-off in several ways. The audience has been trying to figure out how our hero’s going to sort out the bad guys, and clean-up the town of Bottleneck, without resorting to lawless violence, himself. Well, the answer is that he doesn’t. Instead, he quite understandably snaps. He simply straps on his six-shooters and sets out for vengeance.

From that point on, the finale seems to come out of nowhere and rushes to its conclusion. The brave feminist subtext suddenly erupts into an incongruous showdown of women armed with hoes and rolling pins against the gun-toting men. The death of one of the main characters is a catalyst that instantly sorts out which side everyone’s on… and it all ends with a bang. Literally. There’s tragedy and deserved retribution. Then a little light relief as a sort of palette cleanser and …well, that’s that.

With a budget of around $700,000, it wasn’t a cheap film for the day but quickly earned it back, grossing $1.6M at the box office. Sequels were discussed but never made, though George Marshall directed a remake, starring Audie Murphy as Destry (1954). There was a successful Broadway musical based on the film, too, with music and lyrics by Harold Rome, starring Andy Griffith and Delores Gray as Frenchy. Again, it was the Felix Jackson film script, not the original novel, that inspired the ABC television series, Destry (1964), with John Gavin playing Tom Destry III, the son of Stewart’s version.

The film’s influence can be seen throughout many Westerns that followed. There’s more than a trace of the story in High Noon (1952) but its legacy is most obvious in comedies such as The Pale Face (1948) starring Bob Hope, and Support Your Local Sheriff! (1969) with James Garner.

Most of all, the Mel Brooks classic, Blazing Saddles (1974), could almost be a loose remake! The arrival of the sheriff, as he nears the town of Rock Ridge, is a close quote of the similar sequence as Destry arrives in Bottleneck. The chaotic finale that breaks down reality, though ridiculously over the top, could be read as a post-modern reworking of the Destry finale!

I must admit, Blazing Saddles is by far the funnier film… but, alas, it doesn’t have James Stewart in one of his defining roles.

USA | 1939 | 95 MINUTES | 1.35:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

director: George Marshall.

writer: Felix Jackson (based on the novel by Max Brand).

starring: Marlene Dietrich, James Stewart, Charles Winninger, Brian Donlevy, Mischa Auer, Una Merkel, Allen Jenkins, Warren Hymer & Irene Hervey.