HIGH NOON (1952)

A town Marshal, despite the disagreements of his newlywed bride and the townsfolk, must face a gang of killers alone at high noon when their leader arrives on the noon train.

A town Marshal, despite the disagreements of his newlywed bride and the townsfolk, must face a gang of killers alone at high noon when their leader arrives on the noon train.

Even those who haven’t seen High Noon will have some idea of what it’s about, and no doubt can hum its Academy Award-winning theme song “Do Not Forsake Me, Oh My Darlin’.” It’s a powerful parable about one man standing up for his principals and defending human decency in the face of encroaching evil, even as those around him turn their backs. As classic Westerns go, you can’t find one more renowned. It came at the tail-end of the Western’s Golden Age in Hollywood, marking the end of an era as the film industry, along with the nation itself, descended into political paranoia.

At the time, around a third of all movies being made in the United States, and a quarter of all television shows in production, were Westerns. The US seemed to be struggling to assert a new national identity through mythologising their own past. As a result, the revisionist Western was an exhausted genre and there was a need to reflect on history in a way that held a mirror up to contemporary issues.

High Noon has been cited as the first of a new kind of ‘novelistic’ Western—more concerned with characters and themes than the historical setting. Whilst the same story could’ve played out against a Biblical backdrop, a gangster setting, or even as part of a big business Wall Street story, the visually striking opening scene revels in the rich iconography of its genre. The pale landscape gives no real perspective as the land and sky are of the same off-white tone. Trees, horses, and figures look almost illustrative… as if printed on the pages of a book. It’s a series of strong minimalist compositions and this starkness is matched as the initial silence is filled by lo-fi percussion, perhaps suggesting the rhythm of horse hooves. A few sparse strums on a guitar ease us into the titles along with the subdued vocals of Tex Ritter singing the now-famous theme song.

The first face we see is a very young Lee Van Cleef, making his screen debut, as Jack Colby. He’s soon joined by Ben (Chev Woolley) and Jim Pierce (Robert Wilke), both actors well-versed in playing cowboys and henchmen. The trio rides brazenly into the small town of Hadleyville, attracting the attention of the townsfolk, who recognise them as members of the Miller gang. At the dusty station, they ask if the train will be on time and then resign themselves for the wait. We see their faces in close-up, before noticing the details of their spurs, hats, and gun belts.

It’s your typical Wild West station in the dusty plains, with wooden shacks and a water tower. The location was a stretch of real railroad that was repeatedly used in Westerns and is preserved as part of the Railtown 1897 State Historic Park museum at Jamestown, and it’s still occasionally used for filming. The station sequence, which we revisit throughout the film, would be deliberately quoted 16 years later in the opening to an even greater Western—Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)—when three men wait for another train and the confrontation it will bring. Incidentally, one of Leone’s gunmen, Jack Elam, also appears briefly in High Noon as the town drunk, sleeping it off in a cell.

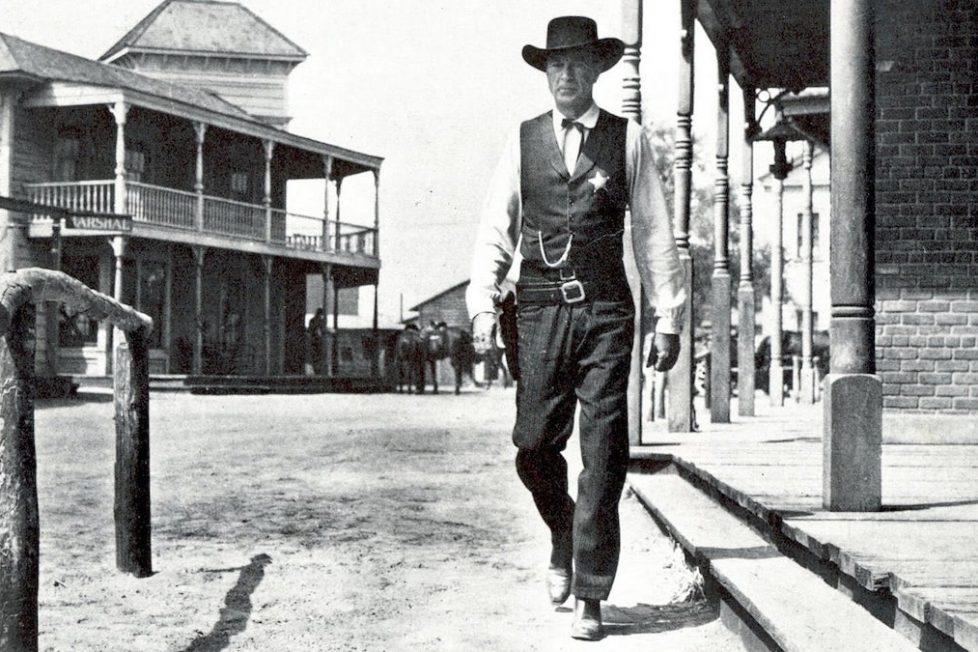

The Hadleyville Marshall, Will Kane (Gary Cooper) has made the mistake of retiring and getting married on the same day… both events that spell impending doom in the world of cinema! Both are also archetypal motifs that signal transition and change. Shortly after he’s taken his vows with his young wife, Amy (Grace Kelly, in only her second big-screen appearance), a telegram arrives to let him know that Frank Miller (Ian MacDonald) has been released from jail and will be arriving on the noon train set on murderous vengeance. Kane’s urged by everyone to leave Hadleyville fast and get on with the honeymoon, but as he and Amy ride away we watch their faces change through an array of expressions and, with hardly a word spoken, we can see that Kane can’t run away from his duty to protect the town.

Apparently, Cooper, who was an A-list star throughout the 1940s, liked the script so much he’d agreed to take half his usual salary. He’d just turned 50 and wasn’t in great shape, so knew his days of playing Hollywood heartthrobs were over. What attracted him to the script, besides its atypical take on the genre, was Kane’s minimal dialogue. He saw an opportunity to emote only through facial expressions and body language and showcase his character-acting skills.

The script was written by Carl Foreman and began life as an adaptation of The Tin Star, a 1947 short story by John W. Cunningham, published in Collier’s Magazine, that also draws from Owen Wister’s 1902 novel The Virginian. But as Foreman wrote his version for the screen, things fell apart around him and, as he watched Hollywood succumb to the ‘Red Scare’, he began altering the story into a clever work of meta-fiction.

After World War II, there was a concerted effort by the right-leaning government to influence the media and control the messages it put out. The original short story was published the same year as the awkwardly named House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began their infamous investigation of around 80 Hollywood writers, directors, and producers accused of subverting their films to include Communist propaganda.

As there were no crimes involved, most of those cooperated, admitted their political alignments and gave up names of known Communist Party members. But some saw where this was heading and refused to respond to the HUAC interrogations and, with no criminal charges, they claimed protection under the First Amendment’s right to privacy, freedom of speech, and freedom of thought. Of those who resisted, 10 were selected to be made examples of and, although they’d broken no laws, were fined and given prison sentences ranging from six months to a year. These are now remembered as ‘The Hollywood Ten’.

These despicable proceedings had been going on for the four years Carl Foreman had spent honing and pitching his story. By the time he had got the production together as an associate producer with Stanley Kramer, and with Fred Zinnemann as director, Foreman himself had come under the scrutiny of the HUAC due to a former association with the Communist Party. He continued tinkering with the script even as the cameras rolled and subtly worked in new scenes and dialogue to reflect the real world around him. The central theme of past actions coming back to haunt the protagonist and finding the strength to speak truth to power thus takes on a new layer of symbolism.

We learn that years earlier Frank Miller was sent down by Marshall Will Kane and expected to hang but was instead pardoned. Possibly the most telling scene is when Kane goes to the Judge (Otto Kruger) to ask for help in sorting out the potentially deadly situation but, instead of helping, the judge, whilst packing up his own flag of the union and law books, also advises Kane to leave town. There’s a fantastically powerful shot as Frank Miller’s threats of revenge are recounted. It’s simply a slow zoom on the empty chair where he’d sat five years before and sworn to return and kill Kane.

The Marshall soon finds that nobody will support him in his stand against the Miller gang, who it seems used to run the town before he cleaned things up. Even his new wife decides to abandon him, rather than compromise her bone-deep pacifist principals as a Quaker. His Deputy, Harve (Lloyd Bridges), also refuses to stand by Kane unless he guarantees his promotion in place of the new Marshall who’s scheduled to arrive the next day. For reasons demonstrated later, Kane refuses this ultimatum as he believes that his young Deputy isn’t yet ready. Harve responds by laying down his own badge and pistol and walking away.

It seems even those he thought were good citizens find some excuse to look the other way, stemming from fear or the possibility of personal gain after Kane’s death. The barber (William Phillips), who’s also the undertaker, does some quick maths and, weighing up the odds, orders four coffins… another piece of gallows humour that would be replayed by Leone in his Spaghetti Westerns.

The only other major player to make any difference is Helen Ramírez (Katy Jurado), who was apparently Frank Miller’s woman once, then Kane’s, and is currently in a relationship with the Deputy. She’s a strong independent woman who still loves Kane and has a woman-to-woman chat with Amy that seems to have a delayed effect on her decision to leave town.

Foreman’s script is stripped back and deceptively simple. It expects the audience to be paying attention and intelligent enough to grasp the subtleties and fill in the gaps. Some of the dialogue veers a bit too close to melodrama for my liking, and at times there are names mentioned in passing that take a while to sink in. It feels a bit clumsy here and there but falls into place before the finale. It made better sense on second viewing, although some incongruities become more noticeable. There are a few minor problems with continuity and a couple of anachronisms that would only bother eagle-eyed historians.

The visual style reflects the script’s simplicity. The beautifully composed, though often stark photography, was in the hands of Floyd Crosby, who had mainly photographed documentaries and was only just transitioning into feature films. As would be expected, the camerawork is solid and realist, though it was Cooper’s own suggestion that he wore no makeup, so every line of his face would be clear in the many closeups and the sweat would glitter in the bright sun. Crosby makes good use of key-lights in many of the close-ups, making Cooper’s expressive eyes sparkle as if brimming with barely held-back tears.

The town has a large number of clocks and there’s often one in the background. This helps to highlight the inventive narrative device of having the action play out in real-time. When the fateful telegram arrives, after the first 10-minute set-up, Kane glances at a clock that tells us he has 80-minutes to sort things out—-also the remaining duration of the movie. Repeated shots of clocks throughout provide a countdown for the audience and evoke a slow tension and building urgency. The many signs and notices in the background are also used to great effect and often seem to be cleverly commenting on what’s going on!

In the final scenes, Hadleyville is deserted as Kane walks out alone to face his destiny, knowing he “can’t be leavin'” until he “shoots Frank Miller dead…” This is, however, an unlikely outcome as the ageing lawman faces four professional gunslingers. His dark figure is picked out against the pale dust of the main street as the point of view elevates in an expressionistic crane shot to emphasise his isolation. There’s no one at hand to help or even to bear witness to his brave lone stand.

This meaningful shot now seems absolutely essential in its place, but was a last-minute innovation. As Zinnemann didn’t have the budget, he intended getting the high angle from a balcony, until he heard that a bigger-budget Western, being filmed on a neighbouring backlot, had hired a ‘Chapman crane’. He had a word with that film’s director, George Stevens, and persuaded him to loan him the crane for an afternoon. That other film was Shane (1953), another game-changing ‘novelistic’ western.

So far, High Noon hadn’t provided the thrills usually dictated by the genre template. There are no hold-ups, no chases on horseback, no gunfights, just a couple of unglamorous punch-ups. It’s finale remedies that with a realist gunfight that itself would prove to be a new genre template.

The biggest irony is that on the same day the climactic shoot-out between Kane and the Miller gang was being filmed, Carl Foreman was brought before the HUAC and because of his refusal to name names, was treated as a hostile witness. He was denied any advocate counsel or legal representation. Just like his script’s hero, he had to stand alone and find his own courage to uphold his principles as a man of conscience.

As a result, even his studio pals, Zinnemann and Kramer, could do little to help him. His associate producer credit was removed, along with its fee, though his writers’ credit remained, and Kramer did manage to settle a severance payment. But that was the limit of the support he could get when the HUAC gang rode into town and changed Hollywood into a bigger, worse parallel to Hadleyville. Having just about seen the production completed, Foreman was blacklisted, which effectively derailed his Hollywood career.

At the time, nobody would’ve expected this film to leave such an enduring legacy. After such a rushed and beleaguered shoot, it was a surprise success, though it divided critics of the day. John Wayne, who’d turned down the lead role of Kane, hated it with a vengeance and called it “the most un-American thing I’ve ever seen in my whole life.” Although it didn’t deliver what audiences expected of a Western, it was a box office hit and brought in $3.4M from its initial theatrical run in ’52, easily covering its B Movie budget of $730,000. It just goes to show, audiences don’t always know what they want!

It was nominated for seven Academy Awards and won four of them: ‘Best Actor in a Leading Role’ went to Gary Cooper, Elmo Williams and Harry W. Gerstad shared ‘Best Film Editing’, Dimitri Tiomkin won two statuettes, the first for ‘Best Score’ and another for ‘Best Song’ (which he shared with Ned Washington for “The Ballad of High Noon”, a.k.a “Do Not Forsake Me, Oh My Darlin'”.) It’s rather telling that the remaining three nominations were ‘Best Director’, ‘Best Picture’, and ‘Best Screenplay’, which would’ve gone to director Fred Zinnemann, producer Stanley Kramer, and writer Carl Foreman, respectively. Perhaps their recent run-ins with HUAC had impacted their chances. Katy Jurado was the first Mexican actress to win a Golden Globe Award, for ‘Best Supporting Actress’ as Helen Ramírez, and another Golden Globe went to Floyd Crosby for his ‘Cinematography’.

In a nice little twist of fate, Gary Cooper was filming abroad when the Oscar ceremony was held. So he asked his friend, John Wayne, to collect the ‘Best Actor’ honour on his behalf! I wonder if he was just ‘rubbing it in’…

High Noon was among the first films selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the United States National Film Registry as “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant”. The American Film Institute (AFI) listed it as the second greatest western of all time, sandwiched between John Ford’s classic The Searchers (1956) at number one and Shane in third place. I like the film a lot. It’s undeniably a classic and hugely influential. But for me, there are better Westerns, though I’d have to concede there may not have been if it wasn’t for High Noon!

Gary Cooper had formed a friendship with Foreman and so he tried to help him form an independent company and signed up to star in its first film. Warner Bros. threatened to renege on their contract with Cooper on ‘moral’ grounds if he continued to support the venture. So, just like Kane walks away in disdain, Foreman walked away from the US and resettled in London where he continued to write under pseudonyms.

He and Michael Wilson, another blacklisted writer, wrote the script for The Bridge Over the River Kwai (1957), which won them an Oscar they were unable to collect. Foreman’s screenplay for The Guns of Navarone (1961) was also Oscar-nominated. He became the president of the Writers Guild of Great Britain, received a CBE in 1970 for services to the film industry, and eventually returned to work in the US on the board of the AFI. The statuettes for Bridge Over the River Kwai were finally given, posthumously, to the writers’ widows.

In the telemovie, High Noon: The Clock Strikes Noon Again (1966), Peter Fonda played Will Kane Jr., who arrives in Hadleyville on the noon train 20 years on, to seek vengeance against the sons of Frank Miller for the murder of his father. In 1980 there was another telemovie sequel, High Noon, Part II: The Return of Will Kane, scripted by crime novelist Elmore Leonard and starring Lee Majors as Kane. Tom Skerrit played the part in a TV remake in 2000, too.

It has inspired several reworkings over the years. The idea of a High Noon in space had been the starting point for Peter Hyams when developing Outland (1981) with Sean Connery as an off-world lawman. Cult 1960s TV series The Prisoner references the film with its central premise of one man struggling to maintain his individual integrity and most explicitly in the two consecutive episodes: “Do Not Forsake Me Oh My Darling” and “Living in Harmony”.

The references and parallels, intended or not, in many other movies are too numerous to ponder here… A new cinematic treatment has been in development since 2016, and last year Stanley Kramer’s widow, Karen Sharpe Kramer, announced that the project was back on track with writer-director David L. Hunt at the helm.

director: Fred Zinneman.

writer: Carl Foreman (based on ‘The Tin Star’ by John W. Cunningham).

starring: Gary Cooper, Thomas Mitchell, Lloyd Bridges, Katy Jurado, Grace Kelly, Otto Kruger, Lon Chaney Jr. & Henry Morgan.