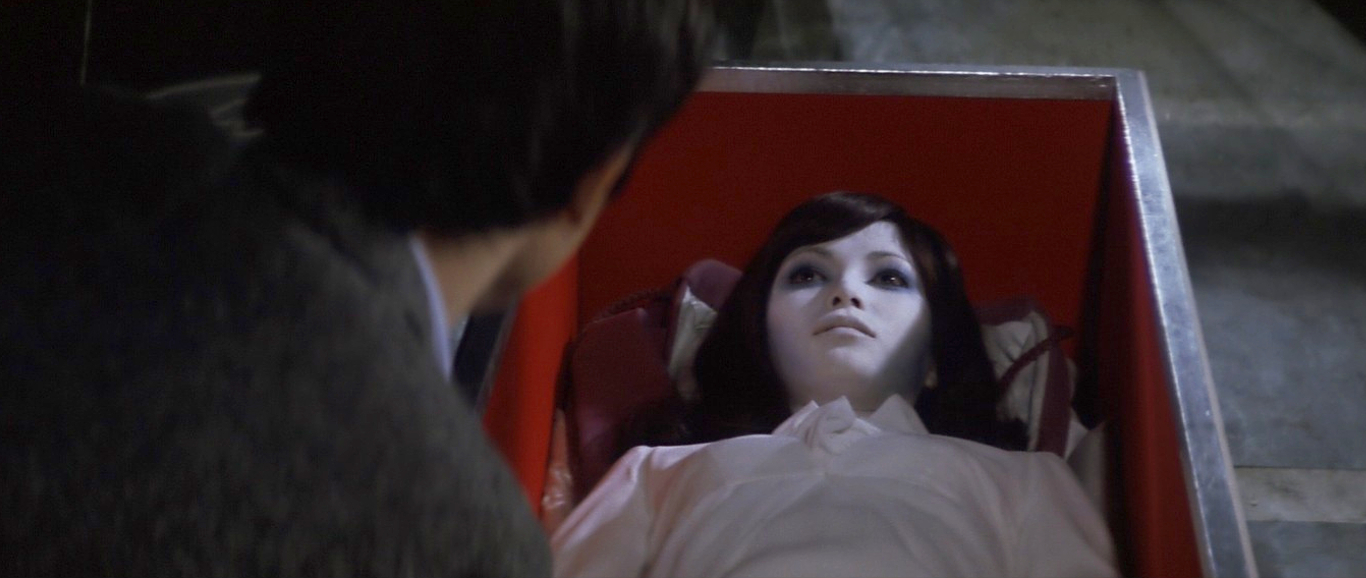

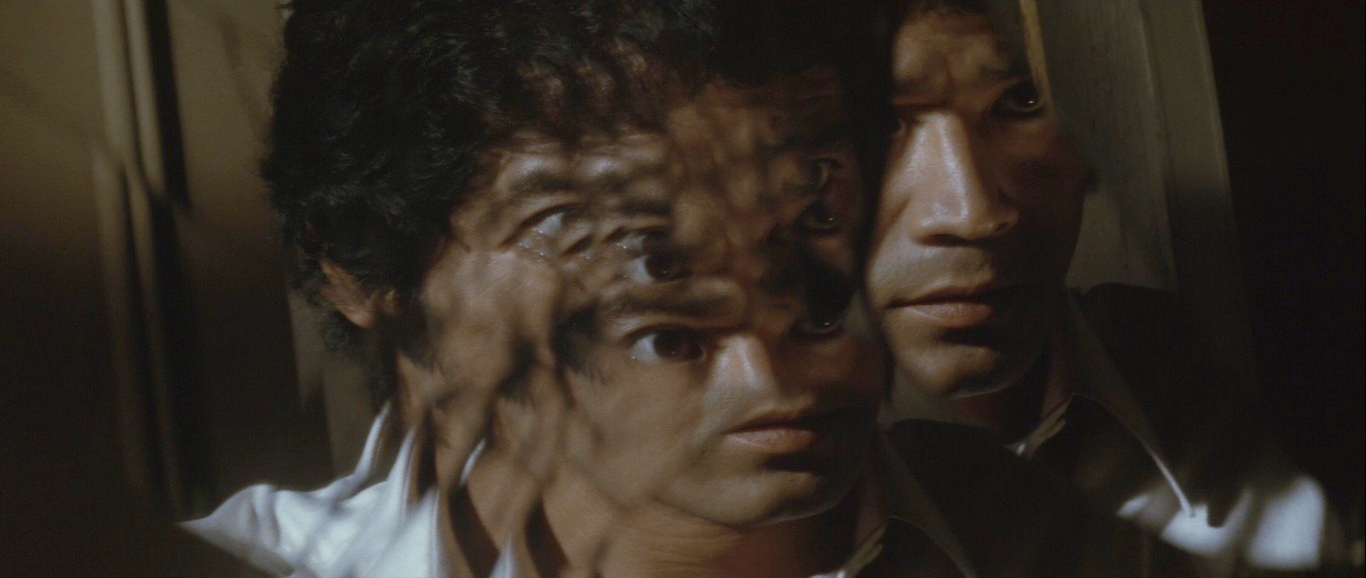

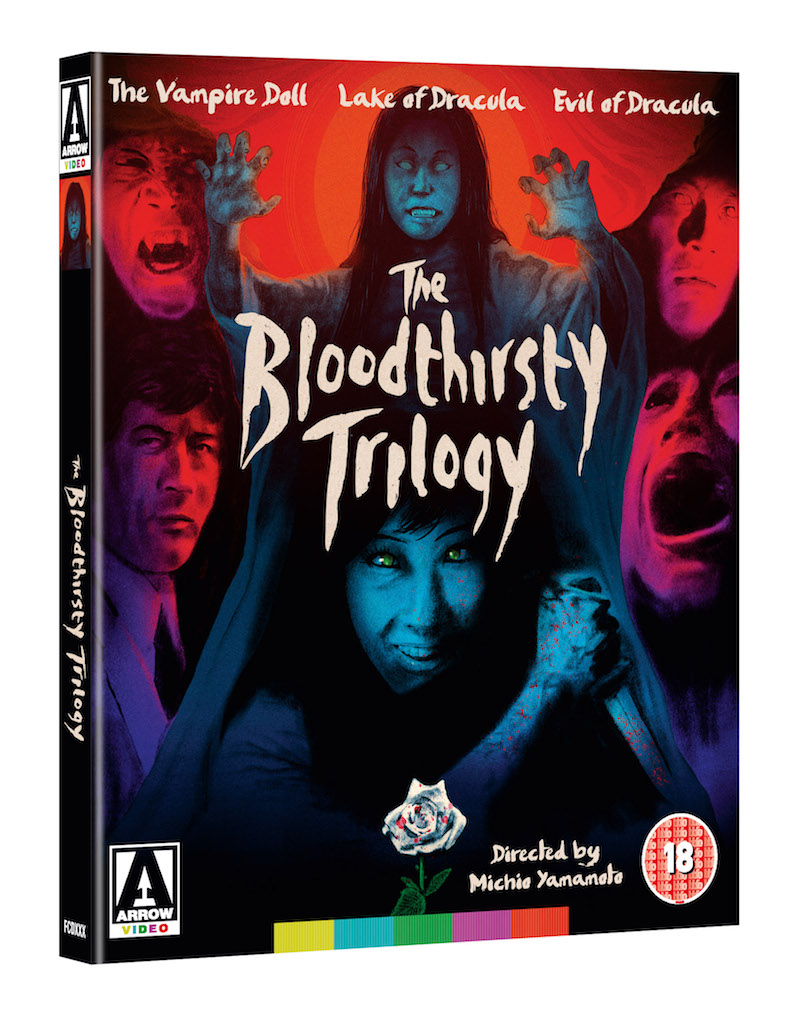

The Bloodthirsty Trilogy: THE VAMPIRE DOLL (1970) • LAKE OF DRACULA (1971) • EVIL OF DRACULA (1974)

Inspired by the success of British and American horror films of the 1960s, Toho Studios brought the vampiric tropes of the Dracula legend to Japanese screens...