STORY OF A LOVE AFFAIR (1950)

A young, beautiful woman married to a wealthy entrepreneur meets her former lover after seven years, but their relationship is marked by tragic events.

A young, beautiful woman married to a wealthy entrepreneur meets her former lover after seven years, but their relationship is marked by tragic events.

Story of a Love Affair was an impressive feature debut for Michelangelo Antonioni, one of Italy’s handful of arthouse heavyweights. Already, most of his recurring obsessions, both visual and thematic, are showcased in this engrossing if odd thriller. The narrative and stylistic innovations he’d later build his international reputation upon are evident throughout.

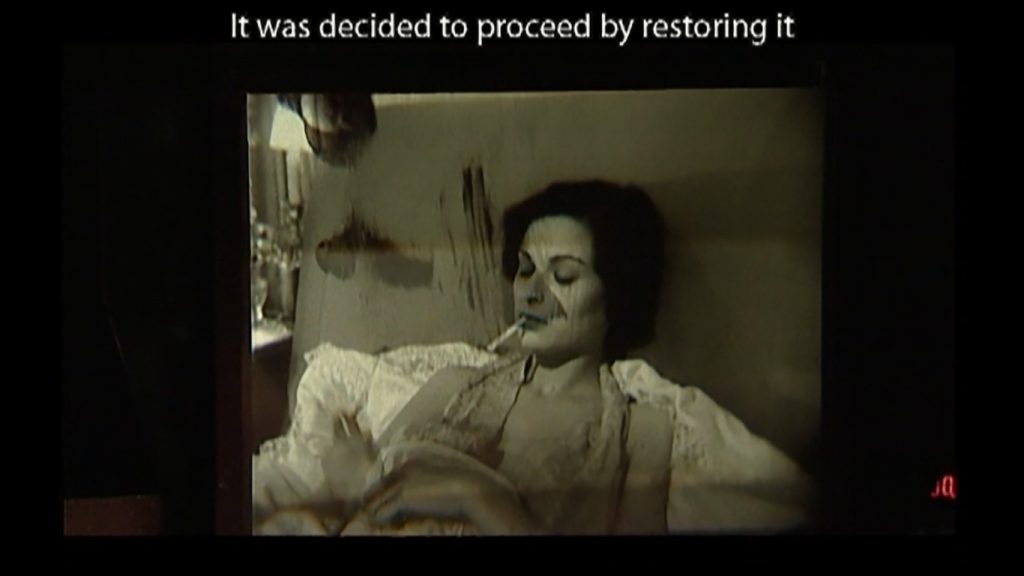

Almost lost forever, due to the original camera negative being destroyed in a fire, Story of a Love Affair was one of the first films to undergo extensive 2K digital preservation back in 2005. The impressively sympathetic restoration was scanned at 2K from a hand-cleaned first generation ’lavender’ print. Now, to mark its 75th anniversary, it’s finally premiering on high-definition Blu-ray, the latest title in the Cult Films collection.

Like most of Antonioni’s films, the story is about the fruitless search for profound happiness. His examinations of existential ennui were to be a huge influence on the nascent French New Wave, with the likes of François Truffaut, Alain Resnais, and Jean-Luc Godard all picking-up on either his thematic or visual style.

A successful businessman, Enrico Fontana (Ferdinando Sarmi), comes across a cache of old photographs in which his young wife, Paola (Lucia Bosè), looks much happier and carefree than she seems after seven years of marriage to him, despite the expensive cossetting he lavishes on her. He develops a kind of retrospective jealousy and hires a private detective called Carloni (Gino Rossi) to investigate her youth.

Carloni visits the people and places associated with Paola’s childhood and teenage years. We follow as he stands outside schools, parks, and sports grounds, talking to her old teachers and people who knew her, building up a picture of a vivacious youngster who everyone seemed to like. It’s a great set-up and the subsequent investigation is a surprisingly absorbing way to tell a story without the need for dramatic flashbacks or much of a budget.

His investigations eventually uncover a tragic accident involving Paola’s best friend, and Carloni surmises that this is probably what underpins her enduring sadness. However, his snooping has disturbed ghosts of her past and Guido (Massimo Girotti), her sweetheart from adolescence, is prompted to contact her again. It seems that he and Paola do have something to hide and assume Carloni is on police business, reopening a ‘cold case’ that may incriminate them both. Fuelled by this mutual paranoia and the remnants of their teen love, they rekindle their relationship.

Interestingly, only one of the principal cast was a professional actor at the time—though, on the whole, they all carry their roles at least competently. Lucia Bosè had been a waitress until just a year earlier when she won ‘Miss Italy’ and was just beginning to get film offers, with Story of a Love Affair being one of the first. She certainly looks the part and makes the haute couture gowns look good too. For the most part, that’s all she really has to do and Antonioni directed her to underplay most of the scenes, though she does verge on the melodramatic at times with much nostril-flaring and knuckle-biting—hey, she’s Italian!

Ferdinando Sarmi joined the production as the costume designer. Those ostentatious gowns worn by Bosè are his creations. Apparently, Antonioni got his services cheap in exchange for a speaking part. Gino Rossi, who has a great face and is perfect in the part of the detective, was the production manager.

Massimo Girotti was already a decade into a prolific career that would see out the millennium. He had played a similar role in Luchino Visconti’s Obsession (1943), which also draws heavily upon James M. Cain’s 1934 novel The Postman Always Rings Twice as its source material.

Here and there, performances are hindered by the dialogue being over-dubbed in post-production, sometimes jarringly. This was the norm for the time as location sound was never clear enough and background noise obtrusive, particularly if shooting in city locations. There are times when lips move and no voice is heard and others when there’s clearly a mismatch. These are few and far between and never really detract from the clever compositions that make up for it. For some shots, the camera is unusually placed behind someone’s head, and sometimes our view is obscured by objects, such as super stylish cars and complicated coffee machines, which cleverly avoids such issues!

Just like the visuals, the score by Giovanni Fusco can also be obtrusive. On occasions, it seems like someone’s just put a record on the phonogram and whacked-up the volume. But this isn’t a big problem because the music’s so cool and jazzy, making it a welcome intrusion for the most part. Fusco would go on to collaborate on the music for most of Antonioni’s films.

The second half of the film plays out like a low-key noir with all the scheming manipulation and moral ambiguity bubbling under the glossy surface of Paola’s bourgeoise life of endless shopping, society parties, and boring bridge nights. The respite afforded her by an illicit love affair with Guido brings back some of the carefree excitement of her youth. But they still can’t quite hang onto their happiness.

They do a lot of moodily looking off into the distance. Guido fiddles with cigarettes as Paola stands facing the wall whilst she talks. He’s crumpled and cool, she’s pristine and uptight. Together, they hatch a callous plot and this strand is loosely inspired by The Postman Always Rings Twice… but the story only ever plays with genre predictability and the plot never unfolds quite as one expects. This may end up delightfully engaging though ultimately elusive, or pretentiously ponderous and frustrating, depending on one’s mood whilst watching.

I found the story dragged a little in the middle and the plot sort of dissolved for a while. It seemed like the real story was happening elsewhere. On the all too rare occasions when we re-join Carloni, things always get more interesting. Antonioni keeps teasing us with aspects of gumshoe, a procedural mystery that never quite gels. This is a kind of perversion that will surface later, particularly in his better-known English language offerings. Blow-Up (1966), starring David Hemmings, springs most readily to mind.

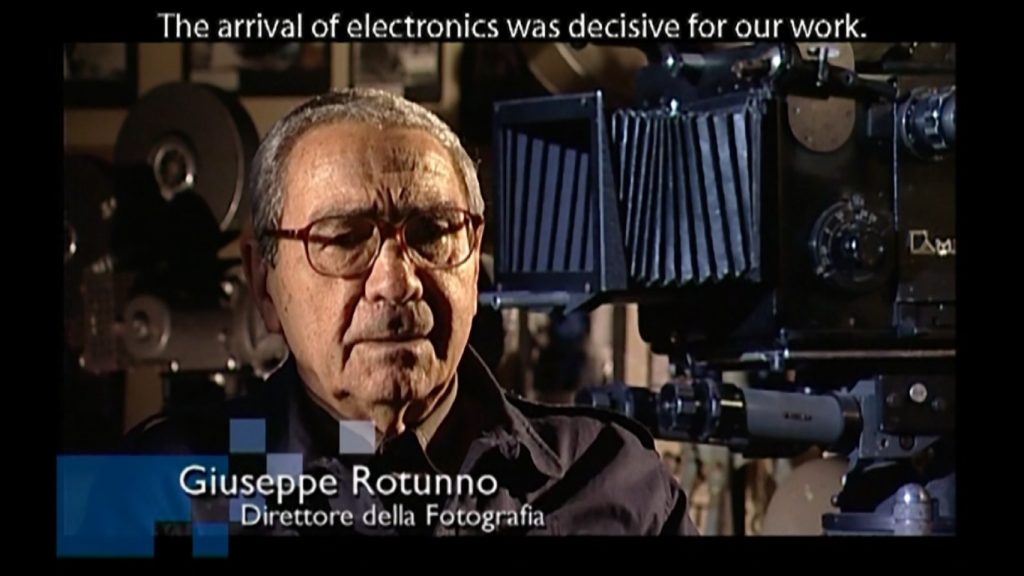

Regardless, though, there’s much to be enjoyed along the way in pure visual flair. Enzo Serafin’s cinematography is often beautiful in itself. Although he was using film stock sourced on the cheap, after it had already been discarded as ‘spoiled’, he turns a shortcoming into a plus, celebrating the varying textures and film grain that lend some of the location shots an ethereal quality.

He also rose to the challenges of Antonioni’s long ‘sequence shots’ where the camera tracks in from long-shot to close-up without cuts. There are a couple of these, the most famous one taking place on a bridge which opens with the view of a car approaching in the distance and then joins two characters on a bridge. The viewer is brought into the scene as if we’re a ghost, unseen by the actors. This particular shot is incredibly well-planned and executed, moving through varying lighting conditions and smoothly pulling focus. Many filmmakers, notably Dario Argento, cite this as an indelible influence on their own style.

It’s very impressive, especially given the cumbersome cameras and stubborn lenses of the era. It clearly draws upon traditions of Japanese cinema in treating the camera’s point-of-view as mobile through 360 degrees within the mise en scène, and it would influence many directors to come.

Max Ophüls would attempt to ‘out-do’ Antonioni in Le Plaisir (1952) with some stunningly complex tracking and dolly shots. Many more modernist and New Wave directors would also be inspired to mimic this distinctive approach to freeing the camera, so much so that it no longer seems unusual at all.

Story of a Love Affair is very much of its time. To audiences today, it may not seem all that ground-breaking but, at the time, it stood out—not only for stylistic reasons but for its break with the dominant Neo-Realism that had become a tradition in Italian cinema. Although its story focus is firmly fixed on the lifestyles of the rich, it’s aggressively critical of them. So, in that respect remains faithful to upholding working-class values of Antonioni’s Neo-Realist roots.

It was certainly an assured debut, but that shouldn’t really be all that surprising as Antonioni had been embroiled in the world of film since the mid-1930s. He started out as a newspaper film critic and then wrote for the state-approved journal Cinema, based in Rome and edited by Vittorio Mussolini. Yes, Benito’s son!

Antonioni’s views were at odds with the officially Fascist publication and he was fired soon after joining its stable. His move to Rome and a brief stint at film school opened doors for him. He earned some recognition for his script-writing, collaborating with Roberto Rossellini to write Un Pilota Ritorna / A Pilot Returns (1942). He also worked in France as an assistant director to Marcel Carné on his fantasy period drama Les Visiteurs du Soir / The Devil’s Envoys (1942), in which the devil is believed to be a veiled metaphor of Hitler and his rise to power.

Around this time Antonioni began to make his own short films with a view to combining them into a dramatised documentary in the Neo-Realist style about the lives of working-class people in the Po Valley region in Northern Italy. His project was interrupted by the war when he was drafted and the footage was confiscated.

He managed to reclaim some of those films after the war and made what he could with what little survived, editing them together as Gente del Po / People of the Po Valley (1947), a 10-minute short. One positive thing the War did was shake up Italy’s socio-political scene and its industrial structures, presenting fresh opportunities and a desire for change.

Between the wars, the Italian Futurist movement, a politicised group of artists, introduced some radical avant-garde notions. They rejected traditionalism and embraced any and all modern technologies of the time. Notably, they declared that film was the only ‘polyexpressive’ medium because it combined visual and audio art with drama, performance, poetry, sculpture and photography. Some of the earliest experimental films had been produced in Italy as early as 1912.

The Futurists tended toward Fascist ideologies and fell from favour in post-war Italy. However, the groundwork had already been laid and the conventions of the nation’s cinema irrevocably challenged. Their influence can be sensed in Antonioni’s love of clinical, Modern architecture and his camera’s dynamism. He often sets scenes of awkward, messy emotions against brutalist backdrops of clinical concrete locations. In Story of a Love Affair, a key scene develops on the austere, terraced banks of a reservoir.

The intangibility of human emotions, their confounding complexity played out against the hardness of a modern urban setting, in all its clean straight-lined simplicity, is a recurring motif in Antonioni’s work. His figures are often isolated against bland backdrops, empty streets, almost alone. Yet there are enough people occasionally passing by to imply prying eyes and paranoia. It’s always milieu before plot, or you could say style over substance, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing and is what keeps Story of a Love Affair watchable!

Antonioni has much in common with that other revered director of the Italian avant-garde, Federico Fellini, who also made his feature film debut the same year with Variety Lights (1950). They had both honed their skills with the father of Neo-Realism, Roberto Rossellini, and they later collaborated on The White Sheik (1952).

Antonioni’s second feature, The Lady Without Camelias (1953), would once again star Lucia Bosè, who would go on to have a busy career making more than 50 films, her final one in 2013. Sadly, she died earlier this year so this Blu-ray debut for Story of a Love Affair is a poignant and timely tribute.

ITALY | 1950 | 102 MINUTES | 1.33:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ITALIAN

director: Michelangelo Antonioni.

writers: Michelangelo Antonioni, Daniel D’Anza, Silvio Giovannetti, Francesco Maselli & Piero Tellini (story by Michelangelo Antonioni).

starring: Massimo Girotti, Lucia Bosè, Gino Rossi, Marika Rowsky, Ferdinando Sarmi, Rosi Mirafiore, Rubi D’Alma, Vittoria Mondello & Franco Fabrizi.