TAXI DRIVER (1976)

A mentally unstable veteran works as a taxi driver in New York City, where the perceived decadence and sleaze fuels his urge for violence.

A mentally unstable veteran works as a taxi driver in New York City, where the perceived decadence and sleaze fuels his urge for violence.

For a film whose protagonist is so corrosively lonely, a surprising number of the most memorable scenes in Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver feature one-on-ones that could almost be described as intimate. Some depict Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro) talking with women, and usually hitting the wrong note. He tries to strike up a conversation with the attendant of a porn theatre (Diahnne Abbott, who later married De Niro), but she’s profoundly uninterested; he eats pie on a kind of date with Betsy (Cybill Shepherd), but they end up talking disconnectedly at rather than with each other; he has breakfast with a 12-year-old prostitute called Iris (Jodie Foster), and seems to connect with her better than with the other two. Travis is childlike in his way, after all. At the porn theatre he buys lots of candy, and seems more interested in this than in the sex on-screen.

Travis’s encounters with men can be more alarming. As he drives the presidential candidate Charles Palantine (Leonard Harris) through the New York streets in his yellow cab, Travis—when asked for his political opinions—gradually metamorphoses from starstruck affability to borderline unhinged ranting. De Niro turns the dial up slowly and brilliantly. When Travis first meets Sport (Harvey Keitel), even the cynical, streetwise pimp is unnerved by him toward the end of their conversation. So is a Secret Service Agent (Richard Higgs), who Travis encounters at a Palantine rally, and who recognises him as a potential security threat.

One of the few who isn’t disconcerted by Travis is fellow cabbie Wizard (Peter Boyle); when the younger man confesses that “I just want to go out and really… do something. I got some bad ideas in my head”, Wizard’s advice is simply “go and get laid.” Of course, that’s exactly what Travis can’t do, and possibly doesn’t even want to do. Film critic Pauline Kael saw Taxi Driver as essentially being about the absence of sex, while film scholar David Greven suggested it’s specifically concerned with violence as a substitute for sexuality.

The linkage is seen powerfully in one of Taxi Driver’s most memorable scenes, where Travis’s passenger is an unnamed man—played by Scorsese, the director. Amusingly, the scene involves him “directing” Travis in what to do with the meter, and where to look when the cab’s pulled up outside an apartment building, but his intentions are far from amusing. Visible through a window of the building is (supposedly) his wife, cheating on him with another man, and Scorsese’s character describes at length how he’s going to kill her. He claims he’ll use a .44 Magnum revolver (technically a Smith & Wesson Model 29), which he’s probably familiar with from Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry (1971). Travis says very little, but the idea of the .44 Magnum certainly sinks in, and he’ll seek one out later in the film.

If the Scorsese character’s a fantasist, then so with Taxi Driver is the real Scorsese. As Greven says, it’s “not a film set in a real place” and “not a film about… authentic characters.” This isn’t to say they’re particularly stereotyped ciphers, either, but we never get to know anyone except Travis closely. Our experiences of everyone else in the film, and indeed of New York as a city, are filtered through his perceptions, and as a result possibly unreliable. Travis himself also remains something of an unknown. We can discern glimpses of the man inside, but we don’t fully understand what makes him tick. As a result he can stand for whatever we like: broken Vietnam veterans, perhaps, or for society’s marginalised in general, or for the confused American male, or for nothing at all.

It’s “a film steeped in failure” said Amy Taubin, and “awash in a melancholy longing for some unattainable state of transcendence” according to Greven. Taxi Driver opens like a noir dream with a haunting sequence where Travis drives the night-time streets alone. Coloured lights blur, steam billows, and pedestrians seem somehow threatening. In this passage, conceived by title designer Dan Perri (Star Wars, The Exorcist), all we see of Travis is his wary eyes, watching what might as well be Hades through his windscreen. “You’re in a hell”, he’ll later tell other characters, and toward the end of the film the hanging beads in the prostitute Iris’s room will briefly recall these lights as he tries to rescue her from hell.

Soon, however, the narrative truly begins with a more conventional scene in a taxi company office, where Travis has come to sign on as a driver. He’s vague about his present and cagey about his past, claiming to have been in the Marine Corps. Screenwriter Paul Schrader since asserted Travis is a veteran, though he doesn’t seem to be good at violence and it’s difficult to escape the suspicion he’s more of a military fetishist. For the first time he displays, too, an odd ignorance: he doesn’t understand what the manager means by “moonlighting”, as later he’ll look blank when someone asks “how’s it hanging?”, and is also unaware who Kris Kristofferson is. He’s so disconnected from the world he might as well be an alien.

He gets the job, though, and becomes a taxi driver. Before long Travis is developing an obsession with Betsy, a smart and educated young woman working on the Palantine campaign, whom he’s seen at her office. He manages to meet her by claiming that he wants to volunteer for the campaign, and charms—or at any rate intrigues her—sufficiently enough that she agrees to go to a coffee shop with him, and subsequently to the movies. The movie he chooses is a porno, though, and she walks away disgusted.

After Betsy’s rejection, Travis becomes steadily more obsessive. He seems to be preparing to assassinate Palantine, and also becomes determined to rescue Iris from prostitution. Those two threads converge in a final eruption of violence. It seems unlikely Travis can survive this, but a brief and surprising coda suggests he emerges to applause and celebrity.

What we are to make of this is arguable. It may be a scathing parody of a happy ending, it may be a comment on the way we choose not to see our heroes’ dark sides, or it may all be Travis’s dying fantasy. Certainly, this is where Scorsese’s visual style departs most strongly from the realistic, and there’s something not-quite-of-this-world about Travis’s final passenger, too.

Like so much in Taxi Driver, the meaning of the ending, and indeed the film as a whole, is naggingly inexplicit: almost clear, but not quite. Indeed, throughout, the audience is often in the same situation as Travis, trying to make sense of things. Is Betsy truly nice, or is she just toying with him? Is Iris really a sweet girl, or thoroughly corrupt? Is Travis good, or is Travis bad?

Throughout, the tension builds inexorably, even when the events unfolding on-screen are innocent; De Niro’s Travis is always unsettling, not least through his occasional voiceover, and moments of respite are few. Betsy’s flirtation with a colleague makes us uneasy because we see her openness toward him and know she shouldn’t risk it with Travis, and the cab drivers’ conversations in a café where they congregate (Travis always sat slightly apart from them) are charged for the audience with the fear that he might blow up any moment.

At the same time, though, Scorsese lets us see the world around Travis as well as the man. The New York street scenes are immersive and full of life. There’s a depth of reality to it, the feeling that everything has a story, even in the smallest details. At least one of them invisible to the original cinema audiences: the porn theatre attendant’s reading a magazine article entitled How You Spend Your Money Affects Your Sex Life, which i ironically appropriate.

Bernard Herrmann’s score—sadly his last—adds much to the atmosphere too, alternating simple but clangorous and ominous orchestral phrases with a kind of parody of cocktail-lounge jazz that’s employed even at the least relaxing moments—like when a group of youths throw eggs at Travis’s car, yelling at him. Contrary to the music’s implications, this isn’t Woody Allen’s New York…

All of this is somewhat secondary, though, to the immense presence of De Niro as Travis. A rising young star, already embarked on the career-long partnership with Scorsese that would see them collaborate on nine movies from Mean Streets (1973) to The Irishman (2019), De Niro convinces utterly in a performance that cannily gives us a Travis who’s the same person across his many moods, without ever letting us see who that is person is beneath. (He drove cabs for a month to prepare for the part, too.)

It is difficult to make sense of Travis, but that’s inevitable, because he can’t really make sense of himself. Still, although there’s some truth in Taubin’s suggestion that “Travis is largely a cipher that each viewer decodes with her or his own desire”, there are things that are clear about him: above all that he needs human contact, yet in his own way is as cut off from mainstream society as the whores and junkies he so furiously despises. “I believe that someone should become a person like other people,” he says, but “loneliness has followed me my whole life.”

Unable for whatever reason, and the reason does remain obscure, to “become a person like other people” he consoles himself instead with fantasies—of having the perfect girlfriend (Betsy, who appears “out of this filthy mess” as an unsullied angel), of rescuing a child (Iris), of success (a letter to his parents shows his Walter Mitty side), and of notoriety.

Underneath, though, it’s possible he’s more nihilistic than he’ll acknowledge. Despite his professed efforts at normality he is more against things than in favour of things, after all. And is there self-hate, too? As Greven wrote, “Travis’s sexuality remains an elusive, maddening blank”; there is no obvious physical attraction to Betsy, yet there are hints of a metaphorical gay encounter in his meeting with Andy the gun salesman (two adult men going together to a hotel room in the middle of the day to fondle weapons…)

Among the other characters, the stand-outs are Keitel, who’s wisecracking and tightly-coiled as Iris’s pimp; the phlegmatic Boyle’s older cab driver; and, of course, Foster as Iris, who’s simultaneously a naive child and a matter-of-fact cynical young woman. Harris’s Palantine is interesting, too, as there’s something slightly off-kilter about him, something not quite natural about his rhetoric, and we don’t know whether this is because he’s an untrustworthy politician (putting Betsy in the same relationship to him as Iris is to Keitel’s Sport) or just because Travis sees him that way.

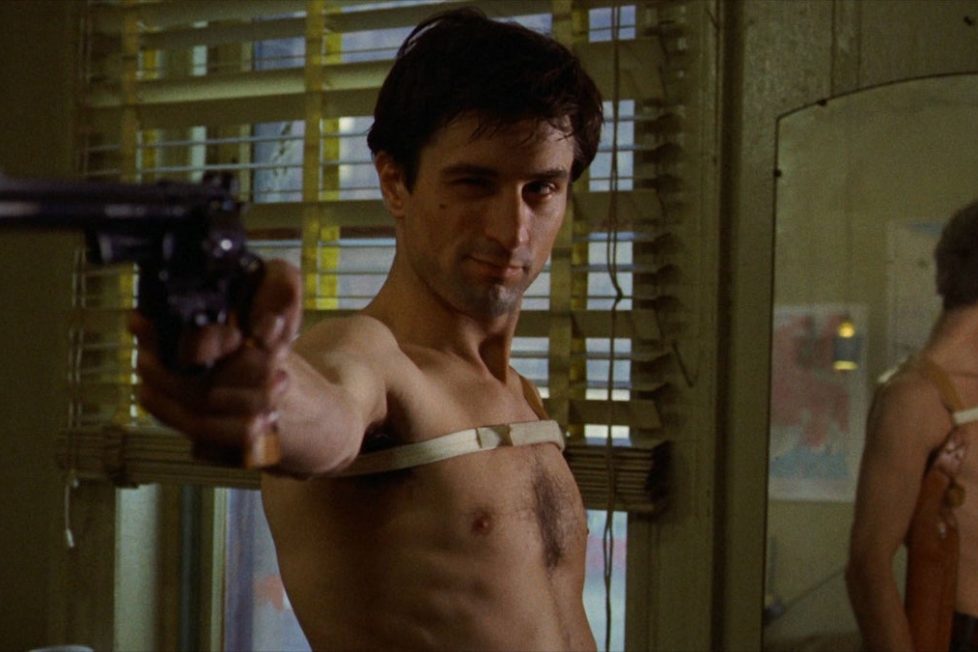

But while they all hold their own in individual scenes, De Niro overshadows them, in part because he gets the only solo moments: most famously his improvised “You talkin’ to me?” conversation to the mirror in his apartment as he practices pulling his gun. It’s in this scene, too, that his racism (always on display but never a primary concern) comes most obviously to the fore, when he aims the gun at a couple of black kids dancing to Jackson Browne on the TV.

Taxi Driver was a significant box-office success (making about $30M domestically on a budget of about $2M) and an even more significant critical success. Roger Ebert found it “a masterpiece of suggestive characterisation”, and “a brilliant nightmare [that] like all nightmares… doesn’t tell us half of what we want to know”. For Variety it was “a sociological horror story” notable for De Niro’s “precise blend of awkwardness, naivete and latent violence” and for its climactic “brutal, horrendous and cinematically brilliant sequence”. It was nominated for four Academy Awards: ‘Best Picture’, ‘Best Actor’ (De Niro), ‘Best Supporting Actress’ (Foster), and ‘Best Original Score’. Though it won none, losing out to Rocky (1976), Network (1976), and The Omen (1976), it did pick up the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, and in any case is now a frequent presence on lists of the greatest movies ever made, rendering its Oscar failure rather beside the point.

If the critics largely loved it, Taxi Driver also made some less enviable fans. Kael wrote that “by drawing us into its vortex it makes us understand the psychic discharge of the quiet boys who go berserk”; among those was John Hinckley Jr., whose attempted assassination of then-president Ronald Reagan in 1981 arose from an obsession with the film and with Foster. “I felt like I was walking into a movie,” Hinckley said of the shooting. But of course Taxi Driver didn’t create Hinckley types out of thin air: Schrader had based it partly on the case of Arthur Bremer, another attempted assassin whose target had been the politician George Wallace in 1972. (It’s not to be seen as a Bremer biopic in disguise, though; other inspirations for Schrader were quite unrelated, for example John Ford’s The Searchers.)

Filmically, Taxi Driver’s legacy can be seen in often unexpected places: not only in Scorsese’s own The King of Comedy (1982) and via that in Todd Phillips’s Joker (2019), but also Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979). Compare the eyes of Travis at the opening with those of Martin Sheen’s Willard in one of the Coppola movie’s most famous shots. Or in the squalid urban dystopia of David Fincher’s Se7en (1995). There’s even a re-enactment of the mirror scene in Mathieu Kassovitz’s La Haine (1995).

That its presence is felt in so many other movies affirms Taxi Driver’s place in cinema history. But it’s not a film that can be reduced to a few passages or ideas; the bulk of its power comes from consistency rather than moments of dramatic change, from the completely persuasive character developed by Schrader and De Niro, and the nightmarish, not quite realistic but all too real world in which he dwells. You can’t really hate Travis Bickle, but you can’t like him either; you can’t entirely comprehend him, but you can recognise him as a frighteningly plausible human being in a world of disappointment and alienation, driving all night but never getting anywhere.

USA | 1976 | 114 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Martin Scorsese.

writer: Paul Schrader.

starring: Robert De Niro, Jodie Foster, Cybill Shepherd, Harvey Keitel & Peter Boyle.