SUPER MARIO BROS. (1993)

25 years ago, the world's first video game to movie adaptation, Super Mario Bros., premiered to widespread condemnation...

25 years ago, the world's first video game to movie adaptation, Super Mario Bros., premiered to widespread condemnation...

Roland Joffé, the British director of Oscar-winning movies The Killing Fields (1984) and The Mission (1986), seems an unlikely person to have orchestrated the world’s first video game to movie adaptation. But, in 1990, noting the enormous success of Nintendo’s Super Mario Bros. games, Joffé and producer Jake Roberts (Chariots of Fire) flew to Japan to meet with the company’s then-president Hiroshi Yamauchi. Their goal? To buy the rights to bring Mario and Luigi to the big screen, despite only raising $500,000 to bargain with.

They received an audience with Yamauchi after a successful pitch of their idea to his son-in-law, Minoru Arakawa. The Nintendo bigwig was intrigued by Joffé’s proposal, as nothing like it had ever been attempted, so awarded them the temporary rights to the Mario characters for $2 million in exchange for some creative control and all profits from the tie-in marketing.

Joffé’s small company Lightmotive could now officially produce a live-action adaptation of the world-famous Super Mario Bros., so they set about hiring screenwriters. Most struggled to accommodate Joffé’s desire that the movie not be exclusively aimed at young gamers. In the wake of Tim Burton’s successful reimagining of Batman (1989) as a darker character, the intention was to appeal to a wider audience by altering the concept into something teenagers and adults could sink their teeth into.

Barry Morrow wrote a script that bizarrely matched the dynamic of his Oscar-winning movie Rain Man, with Luigi as a naive savant to his brother Mario, which was referred to as ‘Drain Man‘ in-house. The closest match to Nintendo’s source material came from Jim Jennewein and Tom S. Parker (Stay Tuned), who wrote a traditional fantasy fairy tale that was reverent to the games, but it just wasn’t the edgy reinterpretation Joffé insisted on.

It proved equally hard to find the right filmmaker for the project, with Harold Ramis and Danny DeVito both turning down offers to direct. Then, the Emmy-winning husband-and-wife partnership of Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel caught Joffé’s attention.

These British directors weren’t big names across the pond, despite a good reception to their remake of D.O.A (1988) starring Dennis Quaid and Meg Ryan, but their 1980s music videos and commercials often utilised cutting-edge computer graphics. Their ad for Pirelli Tyres is recognised as the world’s first fully computer-generated commercial. They also co-created the pioneering cyberpunk TV series Max Headroom for Channel 4, which led to the movie Max Headroom: 20 Minutes into the Future (1985). It was this Joffé thought demonstrated the pair’s inventive approach to technology, and he thought they could breathe new life into the unsophisticated concept of two plumbers rescuing a damsel-in-distress.

Morton and Jankel quickly decided on what became the story’s basic concept: what if an alternate universe has been created by the meteor that impacted the Earth 65 million years ago and wiped out the dinosaurs? In our universe, we evolved from the surviving mammals and now inhabit a lush and advanced planet. But in the other dimension, the population evolved from dinosaurs and now live in a cramped dystopia starved of natural resources, ruled over by a despot called King Koopa.

Parker Bennett and Terry Runte (Mystery Date) were hired to write a script based on this strong sci-fi idea, with veteran comedy writers Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais (The Commitments) brought in to develop the story and enrich the characters. Clement and La Frenais had created numerous classic sitcoms (from Porridge to The Likely Lads), so it was their script that persuaded Bob Hoskins and Fiona Shaw to join the cast. Hoskins famously didn’t even know it was based on a video game, until he mentioned what he was working on to his young son.

It was a f*ckin’ nightmare. The whole experience was a nightmare. It had a husband-and-wife team directing, whose arrogance had been mistaken for talent. After so many weeks their own agent told them to get off the set! F*ckin’ nightmare. F*ckin’ idiots.—Bob Hoskins.

With a then-enormous budget of $48 million, production on Super Mario bros. began in 1992. They immediately set about creating ‘Dinohattan’ inside the large Ideal Cement Factory in North Carolina, where Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) shot its finale. David L. Snyder was brought on to echo his acclaimed art direction for Blade Runner (1982), with Dinohattan’s dark alleys, neon-signed streets, and yellow cabs powered by overhead cables. If there was any doubt Joffé got his way moving Super Mario Bros. away from the colourful and upbeat Nintendo games, walking onto a huge set filled with extras dressed in leather and fishnets made sense of the film’s tagline: ‘this ain’t no game’.

It soon became clear the production was eating up funds, so the producers started looking for other investors. Unfortunately, they had trouble convincing family-friendly studios like Disney that Joffé’s vision for Super Mario Bros. was a wise investment because of its grim tone. Suddenly under financial pressure to make the project more appealing for potential backers, Joffé hired screenwriter Ed Solomon (Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure) for two weeks, asking him to add more comedy to the script.

Unfortunately, the directors weren’t made aware of what Solomon had been tasked with doing by Joffé. When they arrived to begin filming, they were suddenly in possession of a revised script that didn’t match anything they’d been working on in pre-production. The enormous sets built for a grim dystopia didn’t match Solomon’s lighter additions- involving someone walking into a sheet of glass being carried across a street. In protest, Morton allegedly set fire to their storyboards in a car park.

Morton and Jankel discussed leaving the production during long phone calls together, as it was clearly moving away from what they wanted to make. But they decided to stick around because sets had been built, hundreds of people had been hired, and there was a feeling it would be worse to back out at the eleventh hour and almost impossible for a new director to take the reigns with no preparation time.

It was perhaps a fatal mistake. From that moment, Super Mario Bros. was always pulling in different creative directions: Joffé still wanted something close to what Morton and Jankel hoped to deliver, but while he was now willing to make concessions to secure more money… his directors weren’t. The script was rewritten so frequently that Hoskins (playing Mario) and John Leguizamo (playing Luigi) stopped bothering to learn their lines until the day of shooting. Their co-stars Fisher Stevens and Richard Edson (playing dumb villains Iggy and Spike) improvised their first scene’s dialogue as they tailed Daisy through the New York streets, and were allowed to continue doing so because what they said was often an improvement.

A few months into an increasingly torturous shoot, L.A Times journalist Richard Stayton wrote an infamous set report that gave the world its first indication that Super Mario Bros. was having some problems. The directors had started adding ideas from old drafts of the script, attempting to blend many disparate elements together; the production designers often didn’t know what they were supposed to be building or why; and there was a lack of clarity and direction that was starting to exasperate seasoned pros like Dennis Hopper (playing King Koopa). The notoriously difficult screen legend had a loud meltdown during a scene in Koopa’s penthouse over the quality of the writing, which continued into a two-hour lunch with the directors designed to calm the situation, until he reluctantly agreed to shoot the scene as written.

Samantha Mathis (playing archeologist Daisy) had sympathy for the frazzled directors, as they were clearly in over their heads working on an ambitious first-of-its-kind movie involving volatile personalities like Hopper. But her fellow actors weren’t as sympathetic, nicknaming Jankel and Morton ‘The Hydra’ because of their contradictory decision-making. Others started wearing T-shirts emblazoned with stupid comments the directors had made.

After a certain point, the actors started taking the movie less seriously. John Leguizamo admitted in his autobiography that he and Bob Hoskins would often knock back Scotch between takes, aware the film was going terribly and wouldn’t be salvageable. He also started dating co-star Samantha Mathis, which probably helped him get through the shoot. Lance Henriksen (who makes a brief appearance as the King) also met his wife, Jane Pollack, on set. Edson took to smoking pot in one of the beach house’s the production had brought for the cast to stay in, later inviting his co-stars over to unwind with a spliff after each chaotic day.

After 10 long and difficult weeks, money was now so low that the film’s climactic set-piece on the Brooklyn Bridge (where Marion would scale the landmark and drop a Ba-Bomb down Koop’s throat) was canned because it would be too expensive. Its replacement is presumably the brief sequence when Koopa and Mario materialise in Daisy’s dig site, where Koopa ‘de-evolves’ someone into a monkey, before they abruptly return to Dinohattan. There’s also a shot of Dinohattan’s dilapidated version of the World Trade Center replacing our own, which was likely the beginning of a longer sequence where the two cities merge together.

Morton and Jankel were dismissed once the scheduled shooting time expired, despite the film not officially wrapping. The producers were willing to spend a further three weeks working on the film without their involvement, with Mortan and Jankel having to appeal to the Director’s Guild of America in order to grant them access to the editing suite during post-production.

Eventually, on 28 May 1993, Super Mario Bros. had its premiere and received a critical drubbing for its dull aesthetic, confused narrative, and the general lack of fun and emotional connection. But there was some praise for the likeable chemistry between Hoskins and Leguizamo, plus mention of the decent visual effects. It was the first movie to use the now industry-standard Autodesk Flame software (the facial ‘morphs’ and shots of people turning into ‘pixel dust’ were eye-popping for ’93), but its visual achievements looked tame once Jurassic Park premiered two weeks later.

Just consider this movie’s animatronic of Yoshi. It’s a wonderful piece of traditional puppetry that could achieve 64 separate movements, but it was outdated by the time ILM’s computer-generated dinosaurs arrived on the scene.

Super Mario Bros. grossed $20 million, against a production cost of $50m that doesn’t include marketing costs (which are often double what a movie cost to make). A huge box office disaster, its optimistic setup for a sequel wouldn’t be answered until the publication of a 2013 web-comic, and almost everyone involved remains derisive about the film. Although with increasing good humour, as it’s become a so-bad-it’s-good cult in some circles, or is seen as an enjoyable cultural oddity.

I made a picture called Super Mario Bros., and my six-year-old son at the time—he’s now 18—he said, ‘Dad, I think you’re probably a pretty good actor, but why did you play that terrible guy King Koopa in Super Mario Bros.?’ And I said, ‘well Henry, I did that so you could have shoes,’ and he said, ‘Dad, I don’t need shoes that badly.’—Dennis Hopper.

I saw Super Mario Bros. around the time of its UK premiere on 9 July, being the perfect audience for it, as a game-playing 14-year-old boy obsessed with Super Mario World and Super Mario Kart on the SNES. I don’t remember being appalled by the movie, but it certainly left me feeling shortchanged and emotionally detached. I haven’t seen it since, until I started preparing for this retrospective to mark its 25th anniversary, but can now see its many problems more acutely through adult eyes. Knowing the nightmare of its production gives it some added interest, however. It’s fascinating to imagine what aspects were intended by the directors, what was part of the rewrite forced on them, and which scenes were either entirely improvised or the result of last-minute changes. But nothing excuses the sorry mess we’re left with.

I never cared how much Super Mario Bros. played fast-and-loose with the narrative of the games. The idea of there being two versions of Earth, one where dinosaurs evolved, always seemed like a cool idea. It created a fun sci-fi reason for reptilian characters like King Koopa to exist, and seeing Mario and Luigi access this other realm through sewer pipes is a clever way to acknowledge the game’s mythos. There are also some fun nods to some of the game’s iconography, like the Thwomper boots and the wind-up Ba-Bomb.

Hoskins and Leguizamo acquit themselves well as the Mario brothers, particularly considering they hated the experience of shooting this film. It’s a shame the script didn’t focus more on their character’s relationship (which was apparently a larger part of the script they signed on to make), because early scenes of Mario trying to help his brother get a date with Daisy are more engaging than anything that follows.

Their chemistry gets lost in the mix once the brothers arrive in the over-designed Dinohattan, but you never grow to hate watching them together onscreen. The film just becomes a rather tiresome mishmash of malformed ideas that are tonally at odds with what one expects from the source material. And considering this was a hugely expensive movie at the time, even in 1993 it felt strangely low-scale. The Blade Runner-style sets also never impressed me, because they’re shot too much like cheap TV and we revisit the same location too often. Also, what’s up with the opening prologue and the hideously poor graphics used to represent dinosaurs? It seems to have been intended as a nod to the fact this movie was inspired by a video game, but it looks awful and animatronic dinosaurs or hand-drawn animation would have been better.

It also bothers me that plenty of good opportunities are lost. If the Dinohattan realm is inhabited by humanoids evolved from dinosaurs, why do only some of them resemble lizards? Almost everyone could pass for a regular human, so it confuses me why the producers didn’t think to ensure Mario and Luigi would standout in the crowd. Why not given everyone reptilian pupils at least? Or scaly skin? Or forked tongues? Or claw-like fingers? It seems so strange more wasn’t done to make Dinohattan’s population appear more inhuman, but perhaps they couldn’t afford the extensive makeup jobs.

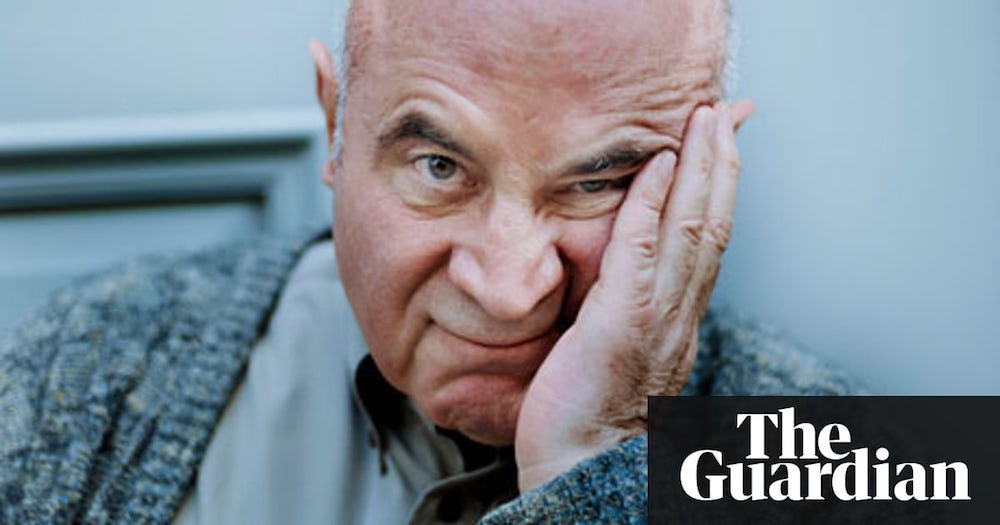

14 years later, still scarred by the experience of making this film, during an interview with The Guardian, Bob Hoskins answered a journalist’s three questions:

Q: What is the worst job you’ve done?

A: Super Mario Brothers.

Q: What has been your biggest disappointment?

A: Super Mario Brothers.

Q: If you could edit your past, what would you change?

A: I wouldn’t do Super Mario Brothers.

One can understand Hoskins’ disdain for a movie that might, with a more cohesive vision, have spawned a successful franchise. Or at least one good movie.

While actor’s careers tend to recover from a box office flop, Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel weren’t so lucky. Super Mario Bros. should have been their ticket to the big time, but instead it killed their Hollywood careers stone dead. In recent times, Jankel directed Sky’s TV movie Skellig (2009) and is currently in post-production on an adaptation of the novel Tell it to the Bees, but Morton’s filmography only contains a few shorts and a segment in a documentary about George Harrison.

Luckily, the negative response to Super Mario Bros. didn’t have any adverse effect on the popularity of Nintendo’s video games. The moustachioed plumbers are still just as popular now as when they debuted in 1985, and while this 1993 movie scared Nintendo away from bringing more of their characters to live-action… plans are afoot for Mario and Luigi to get a second shot at big screen success. A more appropriate CG-animated movie, developed by Illumination (Minions), is in the pipeline. If you’ll excuse the pun.

directors: Rocky Morton & Annabel Jankel.

writers: Parker Bennett, Terry Runté & Ed Solomon (based on characters created by Shigeru Miyamoto).

starring: Bob Hoskins, John Leguizamo, Dennis Hopper, Samantha Mathis, Fisher Stevens, Fiona Shaw & Richard Edson.