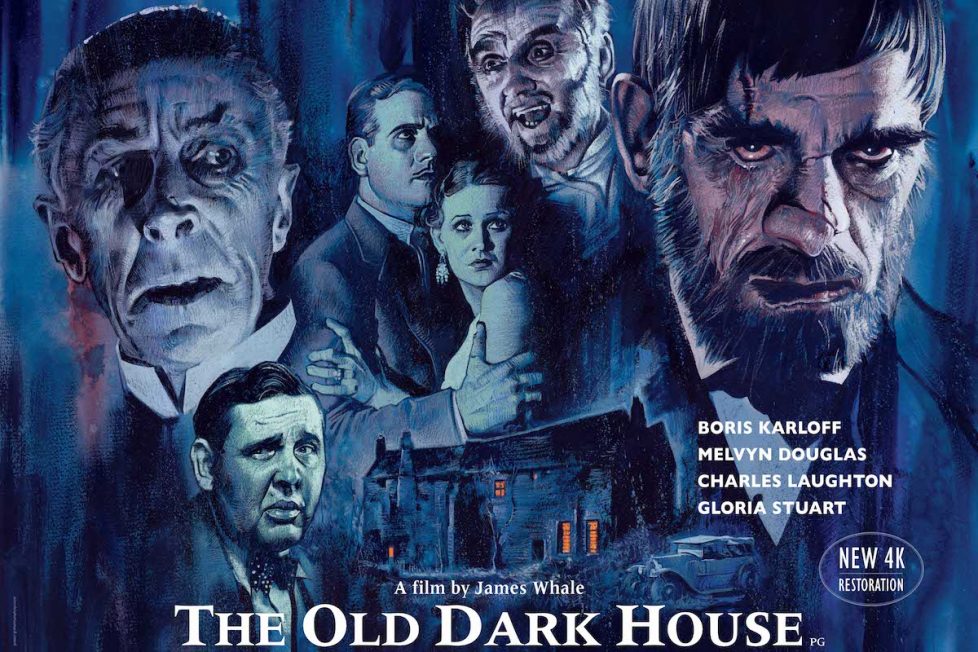

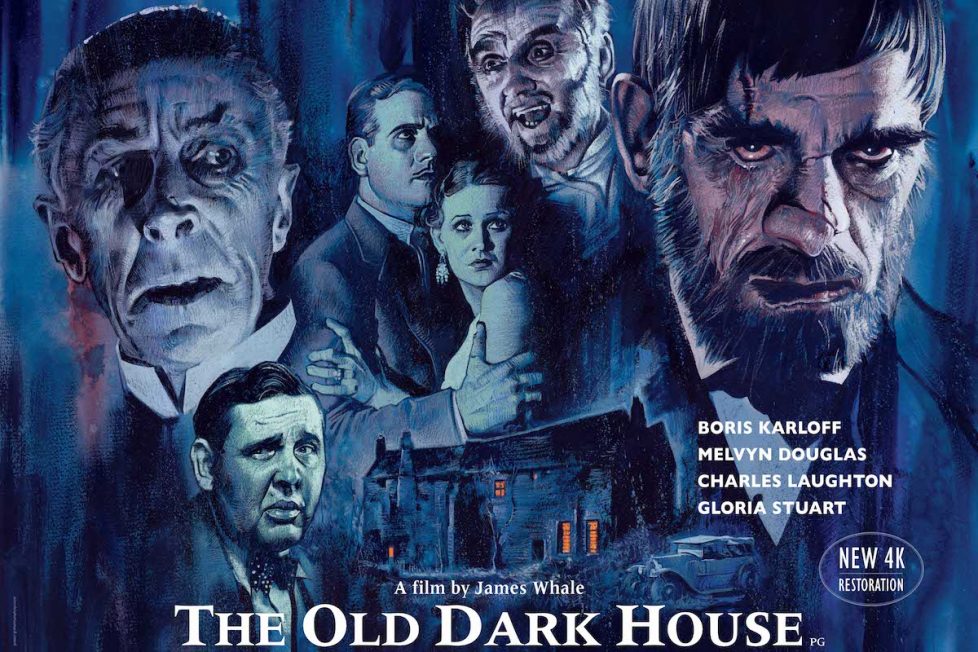

THE OLD DARK HOUSE (1932)

Seeking shelter from a storm, five travellers are in for a bizarre and terrifying night when they stumble upon the Femm family estate.

Seeking shelter from a storm, five travellers are in for a bizarre and terrifying night when they stumble upon the Femm family estate.

The Old Dark House sits uncomfortably between horror and humour. It has a sharp script by Benn W. Levy, with acerbic dialogue containing plenty of wit, along with dark themes and menacing moments that are scary, in a Scooby-Doo sort of way. Director James Whale is best remembered for his contributions to horror cinema, and he’s certainly one of its most influential directors. Cinematographer Arthur Edeson, editor Maurice Pivar, set designer Charles D. Hall, and Boris Karloff, all worked on his genre-defining Frankenstein (1931), and here the same team return to try something a bit different.

I actually found the comedy in Frankenstein more effective, because it was less expected and beautifully counterpointed some genuine horror, like “Hans, give me your hand, Hans.” Though there are many moments of genuine suspense in The Old Dark House and some truly effective direction from Whale, the comedy is a tad too ‘waspish’ for my liking.

A car slides its way through the slurry-soaked roads of the Welsh mountains during the torrential deluge of a thunder and lighting storm. In the car are Philip Waverton (Raymond Massey) and his wife Margaret (Gloria Stuart), bickering away like many old married couples, with their staunch and cheery travelling companion Penderel (Melvyn Douglas) languishing on the back seat. When the road is washed away by a landslide, they still think twice about approaching the titular old, dark house in hope of finding shelter for the night. “We’re somewhere in the Welsh mountains, it’s half-past-nine, and I’m very sorry.” Being a Welshman, I fully appreciated this opening reel, which seemed all too familiar!

The house door is opened by a lumbering, grunting man with a bearded and scarred face. This, as a note from the producers assured us before the film started, is the same Karloff that created Frankenstein’s Monster and any disputes about that would be “a tribute to his great versatility.” Karloff gets top billing as Morgan, the mad butler, though his role is really a supporting one.

The central and standout performance comes from Ernest Thesiger, who greets the strangers by announcing “my name is Femm. Horace Femm.” He may as well have been saying ‘femme’, because he surely isn’t butch… and here he gives us a big hint to look out for a very queer subtext that runs through the entire film.

Despite authoring a book about embroidery and being an archetypal British thespian, Thesiger was in a heterosexual marriage, though was known to “have close male friendships”. His mannerisms and slender elegance do rather suggest a queer bent, and it seems likely that Kenneth Williams may have picked up some of his affectations!

It’s likely those affectations in his performance were the result of direction from Whale, who was openly homosexual. Thesiger’s superb performance is certainly effete, beautifully nuanced in a way that draws sympathy from the audience, and never resorts to the levels of high camp seen in his portrayal of Doctor Pretorius in Bride of Frankenstein (1935). When Horace Femm asks Penderel if he is one of that generation “battered by war”, there’s a hint of irony because Thesiger was indeed wounded in the trenches of the Western front in 1915, when Douglas would’ve been aged 14.

Possibly the most overt expression of non-binary gender is the thinly veiled attraction that Horace’s sister, Rebecca Femm, shows for Margaret Waverton. She can’t resist feeling, first the quality of her fine silk dress and then the smoothness of her pale skin. It’s disguised as a Bible-fuelled judgement of loose morals, but we can see there’s a genuine erotic fixation, coupled with self-loathing, that drives the old spinster.

The bedridden patriarch of the family remains a mystery through the first half of the film, though when finally revealed, Sir Roderick Femm is played by a woman. Credited as John Dudgeon she’s really Elspeth Dudgeon, a British character actress who went on to make more than 60 films over her 25-year career. Now, that’s pushing the gender envelope alright!

Further morality is brought into the discourse with the arrival of another two travellers, forced to seek refuge from the storm. Sir William Porterhouse (Charles Laughton), a brash, self-made man, and his pretty young showgirl companion Gladys (Lillian Bond). They’re not even pretending to be a married couple, and at first Gladys appears to be a typical gold-digger, though her character swiftly develops and gains far more depth by the close of the narrative.

As well as playing with sexuality and gender identity, the film also dwells on the strong social subtext present in its source material, Benighted (1927) by J.B Priestly, his second novel after years as a journalist. Priestley was only just making a reputation for himself having been awarded a prestigious literary prize for his third novel The Good Companions (1929).

Priestly and Whale had a common background, growing up in the Black County of northern England in the aftermath of the Industrial Revolution. Their visual language shared elements of the dark, monolithic smog-enshrouded factory-scapes and both were concerned about the divisions growing between the working, middle and upper classes as well as the geographical split that had divided north and south.

The dimly lit interior of the house and its shadows owe just as much to this imagery as to the obvious influence of German Expressionist cinema, and the whole story can be read as one big metaphor for inter-war England. The house, practically an island isolated by water, is the stand-in for England. The Femm family are the hereditary elite, plagued by insanity and religious fanaticism. The visitors are the relatively new social strata of the middle-class, embodied in Sir William Porterhouse (Charles Laughton), who’ve found fortune through industrialism. Morgan is the uneducated, alcoholic, brutish working class who is not even given a voice, but still terrifies everyone else.

The ensuing Great Depression that followed the 1929 stock market crash blighted the first half of the following decade. The studios were keen to capitalise on any star power they could harness from their contracted talent, whilst at the same time having to enforce wage cuts. Although his role is not the lead, Universal Studios gave Boris Karloff top-billing on The Old Dark House, as part of a failed bid to keep him on contract despite cutting his fees. The next year, Hollywood almost lost Karloff to the British arm of Gaumont, when he returned to his homeland to star in The Ghoul (1933), alongside Thesiger again.

The Old Dark House brought other members of its British cast to the attention of trans-Atlantic audiences. It was the Hollywood debut for Ernest Thesiger and Charles Laughton, both unknowns in the USA. Here the young Laughton looks, and sounds, very much like Peter Kay. Like Whale and Priestly, Laughton was another Yorkshireman and was newly married to Elsa Lanchester, who became one of Horror’s most iconic stars when she later appeared in the title role of Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein.

It also presents us with a kind of whodunnit template that had become immensely popular thanks to Agatha Christie, the British novelist who often employed the device of having a mixed group of characters being brought together in a contained location, such as a country house. This formula has been exploited ever since by countless murder mysteries, horror and disaster movies.

Christie’s 1931 novel, The Sittaford Mystery, is set in another ‘old dark house’, this time in Cornwall, and it’s snow that renders the roads impassable. A handful of her stories had already been adapted into films and, perhaps by coincidence, the protagonist of her earlier murder mystery of 1929, The Seven Dials Mystery, is named Jimmy Thesiger… but years later, both Christie and Ernest Thesiger would contribute recipes for the cookbook, A Kitchen Goes to War (1940).

The Old Dark House knowingly embraces the established formula, but perverts it from a ‘whodunit’ to something that might be called a ‘who-hasn’t-dunit’, for early on in the story we get the idea that some dark deed has happened in the household, perhaps a murder, and all the occupants seem implicated in one way or another. Well, maybe not Horace Femm, we suppose he’s too nervous to have the gumption for any deed too dark, though he’s clearly under the influence of gin and his overbearing sister Rebecca. The film then gleefully throws in plenty more clues and red herrings: various family secrets are alluded to, there are pad-locked doors, forbidden rooms, childlike voices… We begin to suspect that the skeletons in the Femm family closets might indeed be made of real bones!

Some ingredients of The Old Dark House may have been used before, with The Cat and the Canary (1927) being an obvious forebear in mixing Gothic horror elements and dark comedy, but the recipe was new. The comedy in Old Dark House is even darker and pushes the era’s boundaries to a point that becomes uncomfortable. Scenes that start off lighthearted quickly twist into something quite cruel and menacing. Less often does that happen in reverse. And that’s the problem I often find with so called comedy-horror—they become confused and don’t work as either.

The Old Dark House certainly evokes an atmosphere of menace, mainly through the ever-present implied threat emanating from the madness that runs through the entire Femm family, and their butler. There’s a wicked sense of humour that does raise a smile here and there, and when we finally meet the ingeniously insane Saul Femm (Brember Wills), the scene is set for a genuinely unsettling and unexpectedly moving finale. But generally, the satirical tone diffuses the menace and the darkness dulls the smile.

It cleared the ground for the similar dark humour of another unusual family—Charles Addams’ cartoon strip The Addams Family, debuted in The New Yorker in 1938. I don’t think the readership would have been ready for that if not prepared by James Whale and his imitators. But if you want a proper dark comedy about murder and madness running in the family, then you’d be much better seeking out the magnificent Arsenic and Old Lace (1944), in which Mortimer Brewster (Cary Grant) claims “insanity runs in my family. It practically gallops!”

director: James Whale.

writers: J.B Priestley, R.C Sherriff & Benn W. Levy (based on the novel by J.B Priestley)

starring: Boris Karloff, Melvyn Douglas, Charles Laughton, Lillian Bond, Ernest Thesiger, Eva Moore, Raymond Massey, Gloria Stuart, Elspeth Dudgeon & Brember Wills.