28 WEEKS LATER (2007)

A military task force starts to resettle Britain, believing it's now clear of a devastating virus that turns people uncontrollably angry.

A military task force starts to resettle Britain, believing it's now clear of a devastating virus that turns people uncontrollably angry.

What a difference a pandemic makes! Asymptomatic infection may now be the stuff of everyday kitchen-table conversation, but in 2007— when Juan Carlos Fresnadillo’s sequel to Danny Boyle’s refreshing take on the zombie genre, 28 Days Later (2002), was released—it was to most people an obscure and unimportant medical technicality.

But it’s key to the plot of 28 Weeks Later (just as the lack of self-test kits might be the key to a terrifically bleak twist in the film’s final moments), illustrating that at least some of the originality of Boyle and 2002 screenwriter Alex Garland survived into this follow-up.

Unfortunately, and despite Fresnadillo’s best directorial efforts, the premise—a modern Britain thoroughly devastated by the Rage virus, which turns people distinctly zombie-like even if they’re not strictly undead—is inevitably less novel second time round, and even more problematically the film takes a long time to display anything approaching a plot.

The first half-hour is essentially all premise and set-up, and when the principal characters do at last have an urgent need in their lives, it doesn’t add up to much more than a rather abstract “survive pursuit” (largely by the military; as in the first film, they’re at least as much the enemy as the zombies). Never, really, does the movie engage in sufficient detail with the mechanics of how its protagonists are trying to survive for us to be invested in the nitty-gritty of individual scenes.

Fresnadillo’s film opens with a wonderfully foreboding single, long-held musical note on the soundtrack, an early indication that the score by John Murphy—who also composed for 28 Days Later and takes a similar approach here, including the insistent and unsettling repetition of a simple four-note ascending motif—will be one of the best things about 28 Weeks Later.

The first visual image shows us a match striking (life continuing to spark, just about?) and we then meet Don (Robert Carlyle), making dinner along with a small group of survivors hiding out in a barricaded house from the marauding Rage-infected. As in much of the film, this scene is gloomy and seems drained of colour, but when the group briefly takes the risk of opening a door to the outside we see that it is brilliantly sunny; echoes of the match in darkness.

This is only a prologue, however, and soon enough 28 Weeks Later switches to its main storyline with a snappy summary of the story so far. 28 weeks after the Rage outbreak, the infected have died of starvation and NATO forces have established a toehold in the wrecked country; their plan for its resettlement is already underway with some 15,000 survivors brought to a secure zone in London’s Docklands. Among them are 12-year-old Andy (Mackintosh Muggleton) and his sister Tammy (Imogen Poots), a few years older, who come from a refugee camp in Spain to rejoin their father Don.

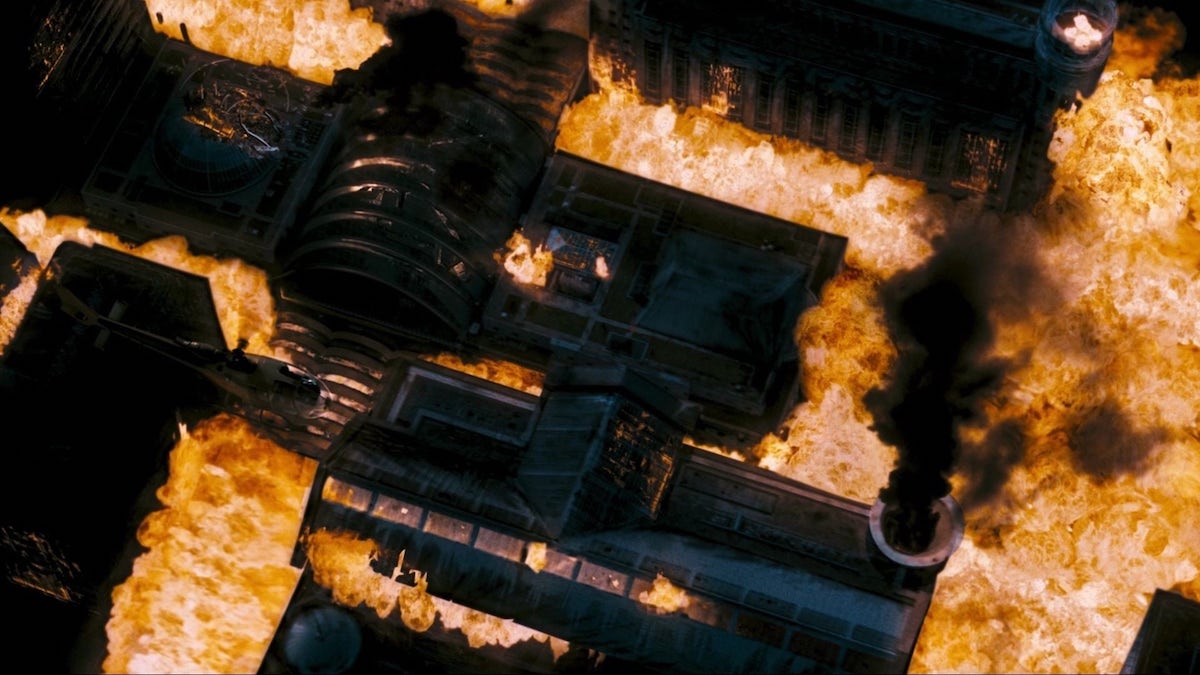

Though the liberation of Britain from the Rage virus is ostensibly a NATO operation, the troops all seem to be American, who soon discover their occupation isn’t going to be as smooth as they’d hoped (shades here of Iraq, or several other places). They’re led by General Stone (Idris Elba), principally responsible for foreshadowing later plot developments (if the virus comes back, he says “we kill it… Code Red”), but we see much more of special-forces sniper Doyle (Jeremy Renner), one of whose duties is to monitor the perimeter. It’s “absolutely forbidden to cross the river and leave the security zone”, so it’s no surprise what happens next.

The bulk of the film, indeed, takes place outside the security zone with Andy, Tammy, Doyle, and army doctor Scarlet (Rose Byrne) trying to evade both the inevitable new outbreak of Rage and the aggressive cleansing operation being carried out by the US military.

The outbreak and immediate panic are thrillingly captured in impressionistic style by Fresnadillo and his team, with a highly mobile camera, fast editing, and strobe-like effects adding to the disorientation. In less action-driven sequences, the scenes of a desolate London in the early stages of decay have as much fascination as they did in the original—compelling in the way that alternate-history images often are—and indeed several moments harken back to the 2002 film, notably two on bridges (here Tower Bridge and the Millennium Footbridge, rather than the Westminster Bridge that Cillian Murphy wandered over in 28 Days Later).

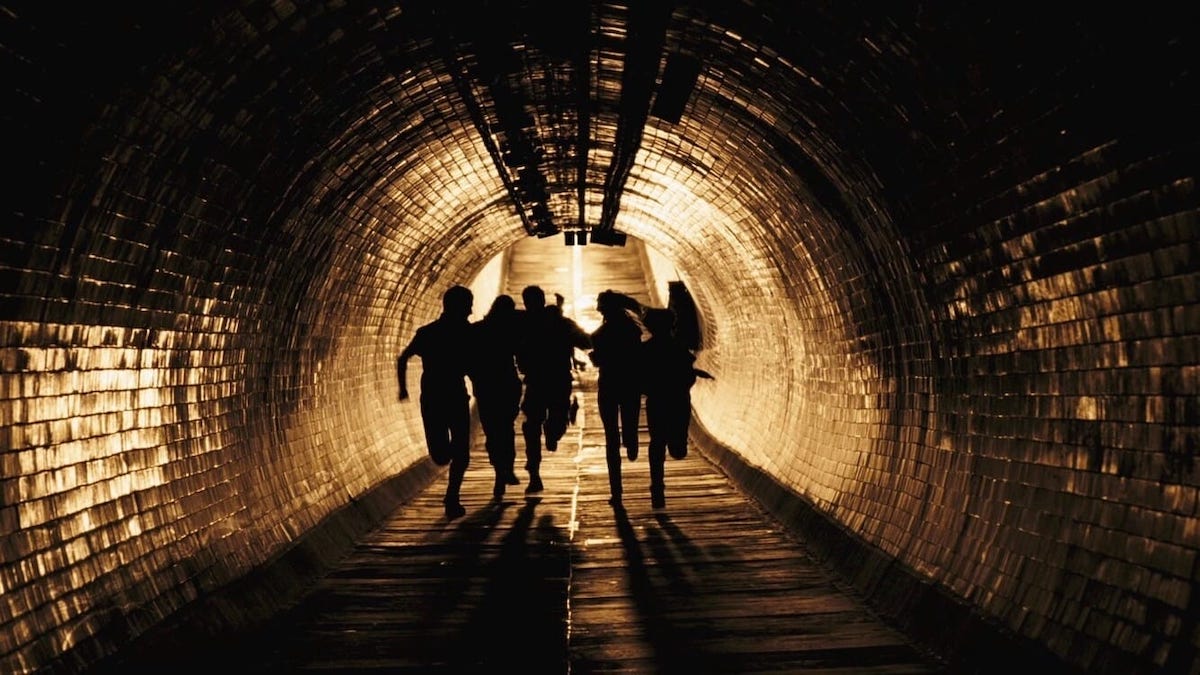

There are many other touches that make one wish Fresnadillo had a stronger story to work with. A scene in a Stygian Tube station is intensely atmospheric though maybe the practical need to rely on a character’s night vision equipment makes the utter darkness not as terrifying as it could be; a shot of an upstairs window in Andy and Tammy’s old home chillingly recalls a similar one in the prologue.

The performances don’t quite match the inanimate settings. Carlyle stands out with his Don, concealing a guilty secret from earlier in the outbreak behind a fake grin; a Rage patient played by Catherine McCormack has an inscrutable, haunted face in contrast. Renner has at least some charisma if no character to speak of, while Poots and Muggleton are engaging enough if faced with the same problem; Byrne is fully characterless, and the rest of the cast isn’t much more than plot devices.

There’s some interesting thinking in the screenplay, too. The idea of a still-functioning wider world attempting reconstruction after a localised zombie apocalypse is not one many films have addressed, while the very end is a pleasing departure from the genre’s usual prioritisation of the individual’s fate over society’s. And the odd implausibility can be tolerated: for example, the military’s efforts to target a few specific individuals seem over-strenuous when they have a much bigger picture to be concerned with, and one zombie’s pursuit of the protagonists appears personally motivated rather than mindless (unless, as in 2016’s The Girl With All the Gifts, we’re supposed to believe that some remnants of personal identity remain in wrecked brains).

These are all minor issues compared with the central narrative weakness at the heart of 28 Weeks Later. It’s fundamentally let down by the combination of thin characters (so flimsy it’s difficult to care about their survival), with the lack of compelling short-term goals for them. They’re also often passive, with much of the plot’s direction being dictated by the military command or by the relatively unimportant figure of a helicopter pilot played by Harold Perrineau, and they are hardly ever given the kind of complex challenge or deadline which would have us on the edge of our seats. It mostly amounts to ‘flee this way a bit, then flee that way a bit.’

For all this, 28 Weeks Later was a commercial success—if not on the scale of the original—and a critical hit too. Fresnadillo’s direction attracted particular praise, though there were also plaudits for the writers: Variety’s Derek Elley thought “the pic wraps a tight-as-a-drum script around a cheeky metaphor for contempo Iraq, with razzle-dazzle dividends”, adding that “it’s to the credit of Boyle and Garland (serving here as exec producers) that they’ve let Fresnadillo and his team…off the sequel leash and allowed them to go for it.”

The film did not, however, propel Fresnadillo to the major leagues as expected, especially coming just a few years after his acclaimed Intacto (2001). He’s sadly only made only one theatrical feature since, although Netflix fantasy Damsel is forthcoming and another for Disney+ may be. Some of the cast—Renner, Elba, Poots—also went on to become bigger names.

A third 28… movie has been repeatedly discussed (presumably its title would have to refer to months, though years would be audacious), and if it ever comes to pass it will certainly be intriguing. There’s surely enough potential remaining in the movies’ semi-realistic vision of the zombie apocalypse, and in the way that they do not assume existing power structures will be completely destroyed, but instead explore how they might react.

In 28 Weeks Later, though, the strong ideas and the vivid directorial handling aren’t quite enough to make up for long ‘so what?’ stretches in the storyline itself. As with an asymptomatic carrier, the essence of something powerful is lurking in there, but it’s not showing on the surface.

SPAIN • UK • USA | 2007 | 100 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Juan Carlos Fresnadillo.

writers: Rowan Joffe, Juan Carlos Fresnadillo, Enrique López Lavigne & Jesús Olmo.

starring: Robert Carlyle, Rose Byrne, Jeremy Renner, Imogen Poots, Mackintosh Muggleton & Idris Elba.