STRANGE DAYS (1995)

A black-marketeer tries to save a woman in 1999 Los Angeles.

A black-marketeer tries to save a woman in 1999 Los Angeles.

The career of director Kathryn Bigelow offers a fascinating trajectory through American cinema. From the outset, she demonstrated an acute fascination with both the dynamics of gender and violence alongside the deconstruction of genre conventions. Early works such as The Loveless (1981) re-imagined biker culture through a subversive lens, while Near Dark (1987) combined a Western and horror cinema into a blood-soaked hybrid. Her overlooked psychosexual thriller, Blue Steel (1990), continued this thematic investigation through a female lens within a male-dominated milieu.

Bigelow’s command of physical intensity and psychological tension earned her mainstream recognition with Point Break (1991), a high-octane muscular blockbuster that combined the visceral spectacle of surfing with a surprisingly introspective exploration of identity and anti-corporate living ideals. After a string of underperforming projects threatened to derail her career, she re-emerged triumphantly, becoming the first female to win the Academy Award for ‘Best Director’ with The Hurt Locker (2008).

Despite the acclaim The Hurt Locker received, Bigelow’s most audacious and arguably finest achievement may be her commercial misfire, Strange Days. What was originally conceived by her former husband, James Cameron (Avatar), the project began as a cyberpunk neo-noir in the vein of David Mamet’s (Ronin) morally ambiguous thrillers.

However, Cameron never intended to fully write or direct the material himself. Instead, he envisioned Bigelow as the ideal filmmaker to bring its volatile world to life. Under her direction, the material drifted away from Cameron’s characteristic romanticism and evolved into a nightmarish vision of Los Angeles on the cusp of the millennium. Combining the gritty sensibilities of urban crime cinema with the heightened paranoia of Y2K, Strange Days confronts controversial subjects such as sexual violence, systemic corruption, police brutality, and the seductive dangers of technological voyeurism. What was once dismissed as a daring experiment in genre hybridity now feels less like a relic of the ’90s and more like a chilling reflection of contemporary anxieties.

Taking place over the last two days of 1999, a dystopian Los Angeles is teetering on the precipice of collapse. The city has become gripped by social unrest, racial tension, police corruption, and technological obsession as the millennium approaches. Former LAPD officer, Lenny Nero (Ralph Fiennes), has re-invented himself as an underground dealer of a machine nicknamed ‘SQUID’ (Superconducting Quantum Interference Device). The headsets capture and re-play the host’s experiences directly from the cerebral cortex, allowing users to re-live every emotion and sensation as if it were their own memory.

While most of Nero’s clientele typically seek the recordings of illicit criminal acts or depraved sexualised fantasies, his world begins to crumble when he acquires a SQUID footage documenting the brutal rape of a sex worker and the murder of a political activist. Realising the recording’s grave implications, he enlists the help of his friend, Mace (Angela Bassett). However, the pair soon find themselves reluctantly embroiled in a labyrinth of murder, conspiracy, and intrigue amid the civil unrest surrounding the suspicious death of a politically active rapper. Pursued by both law enforcement and criminals desperate to suppress the truth, Nero and Mace must uncover the connection between the two in order to stay alive long enough to see in the millennium.

Stepping off the prestige of Schindler’s List (1993) and Quiz Show (1994), Ralph Fiennes delivers an emotionally complex and haunting performance as Lenny Nero. As a disgraced former police officer removed from the force for corruption, the actor oscillates between nervous charm and exhausted desperation. On the surface, he’s a charismatic hustler endlessly peddling illicit SQUID experiences. However, there’s a wounded sensitivity beneath his bravado that makes him far more than a typical cyberpunk antihero. Much like the weary romanticism of Harrison Ford in Blade Runner (1982), he’s a man addicted not only to the memories he sells but to his own past. He’s become reliant on watching playback footage of his failed relationship. Fiennes captures this duality brilliantly, portraying a man spiralling toward self-destruction, both complicit and horrified by the world around him.

After earning an Oscar nomination for What’s Love Got to Do With It (1993), Angela Bassett brings a commanding presence and emotional intelligence to her role as Mace Mason. As both protector and moral compass for the ethically adrift protagonist, she’s fiercely principled and embodies integrity in a world built on illusion. She rejects the lure of the SQUID experience, insisting instead on the necessity of presence and emotional truth. However, beneath her tough exterior lies a palpable vulnerability that anchors the narrative with a sense of humanity. Her affection and frustration toward Lenny reveal the emotional cost of surviving in a corrupt world. It’s a performance that grounds the cyberpunk excess and re-affirms Bassett’s ability to fuse physical power with emotional depth.

The 1990s were a decade suspended between technological optimism and millennial dread, marked by rapid digital advancements that re-shaped the public consciousness. The internet and the concept of digital connectivity were still in their infancy, prompting philosophers and artists to speculate about its transformative and potentially dangerous implications. The cinematic landscape reflected these tensions with dystopian thrillers such as Total Recall (1990) and Johnny Mnemonic (1995) externalising fears of synthetic memories and digital dependency wrapped in genre spectacle.

While Strange Days shares a thematic lineage with the stylised anxieties of Paul Verhoeven and Robert Longo, what elevates Bigelow’s work is her remarkable assurance in transforming the conceit of memory implantation into a haunting ethical enquiry. Rather than indulging in futuristic sensationalism, she anchors her vision in the immediate by grounding the audience in the unsettling plausibility of a world potentially moments away. The infamous opening sequence immediately encapsulates this approach, instantly establishing the psychological and sensory allure of playback technology. Presented through the disorienting perspective of a criminal wearing a SQUID device, the scene captures a robbery spiralling into chaos before culminating with the host fatally plunging from a rooftop. It’s an exhilarating moment that invites the audience to understand why this technology would be popular and addictive.

As the narrative darkens and illicit SQUID recordings begin to surface, there are several moments of intimate real-world violence that expose the depravity already latent in human desire. Several sequences including a graphic sexual assault and the public execution of Jeriko One (Glenn Plummer), refuse the safety of distance. These scenes transform trauma into spectacle and implicate both the characters and the audience in the acts of voyeurism and consumption Bigelow critiques. This interplay between participation and detachment is precisely why Strange Days feels disturbingly prescient and unsettlingly relevant three decades later. Much like Paddy Chayefsky’s Network (1976) anticipated the grotesque theatrics of televised news in ways that no longer seem exaggerated, Bigelow’s vision of experiential technology feels less like speculative fiction and more like a chilling foreshadowing of our contemporary digital condition. In an age when virtual reality headsets and social media exhibitionism have become a commodified experience, the perverse intimacy of the SQUID recordings mirrors our own obsession with consuming experience rather than living it.

Bigelow’s audacious descent into the voyeuristic abyss finds its most potent expression through her visual language. Strange Days undoubtedly remains one of the most visually and technologically groundbreaking works of the ’90s, largely due to its revolutionary cinematography. Bigelow’s uncompromising commitment to realism demanded a series of technical innovations to convincingly achieve the necessary aesthetic for the SQUID recordings. Whether it’s a breathless robbery, a steamy sexual encounter, or learning to rollerblade, these elaborate and highly intense sequences had to convincingly replicate the subjective experience of seeing another person’s perspective while wearing the illicit device.

Unable to find an existing camera system capable of producing this effect, Bigelow entrusted cinematographer Matthew F. Leonetti (Weird Science) to pioneer new methods to achieve the desired outcome. He spent an entire year designing and producing a specially devised 35mm camera that could be mounted on helmet rigs. These lightweight cameras were modified with ultra-wide lenses to mimic the natural curvature of human vision as accurately as possible. Although this technique is commonplace in contemporary cinema, it was a technological marvel during the time when such visual grammar was reserved for video games such as Doom.

It would be an understatement to suggest Strange Days solely as an urban noir cloaked with technological thrills. Beneath its cyberpunk veneer, Bigelow constructs a blistering, politically charged allegory of racial injustice, institutional corruption, and societal decay. The murder at the heart of the narrative, involving the execution of a prominent Blackactivist by police officers reverberates throughout its 140-minute run time. Bigelow has been explicit about the sociopolitical motivation behind the film’s creation. Her anger and frustration towards economic disparity during the 1992 Los Angeles riots that followed the abhorrent Rodney King incident infuse her dystopian Los Angeles with a lived authenticity. As she explained, “Jeriko was very important to me, what he stood for and the broader ramifications”. She continued, “The landscape of a society, a flashpoint society maybe on the brink of civil war, the tensions that were permeating every crevice. It’s not an incredible stretch of the imagination. Anybody who was in L.A. at the time of the riots will acknowledge that”.

Rather than relegate these social realities to the background, Bigelow admirably holds a mirror to America’s racial and moral fractures. The pervasive sense of distrust and the militarised police presence are integral to the film’s architecture. One of the film’s most devastating sequences occurs when Mace experiences the SQUID recording of Jeriko’s murder. As her body convulses and her face collapses into silent agony, she cries to Nero, “I see the world opening up and swallowing us all”. It’s a devastating moment of excruciating authenticity that feels experienced. It’s painfully clear that Mace’s anguish is raw and personal, while the White protagonist, who hasn’t experienced being racially profiled or had his human value degraded, stands outside that shared devastation. Bigelow’s statement is unflinching in this regard, recognising that the apocalypse she envisions is one already long experienced by Black communities.

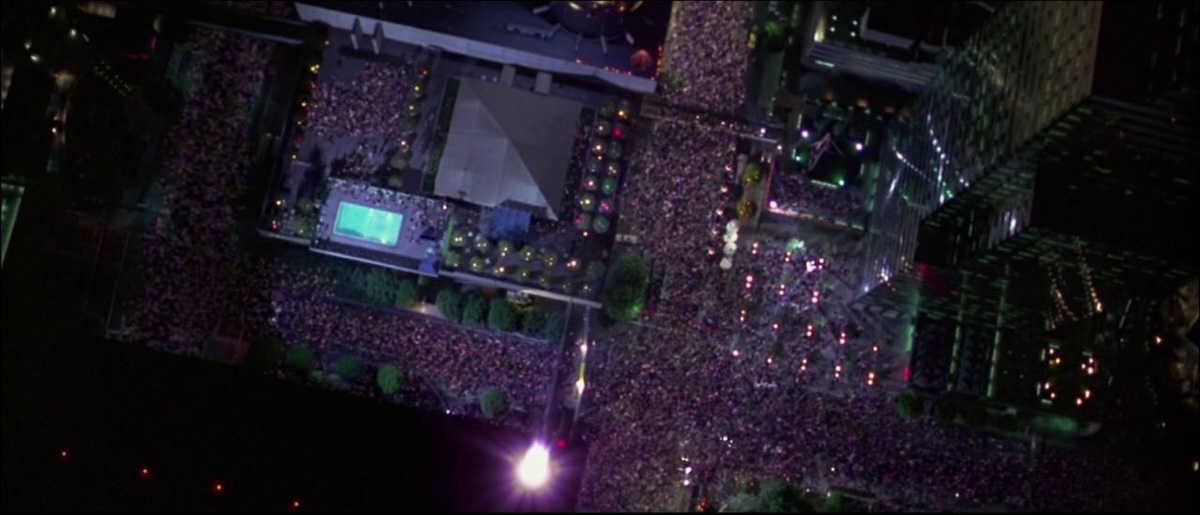

Where Strange Days ultimately stumbles is in the overly convenient resolution of its narrative. Once Police Commissioner Palmer Strickland (Josef Sommer) witnesses the incriminating playback footage, the narrative hastily restores order. Officer Steckler (Vincent D’Onofrio) and Officer Engelman (William Fichtner) are immediately apprehended and proceed to meet their gruesome ends, while fireworks explode over the millennial celebrations of downtown Los Angeles. Civic unrest ends, and the scales of justice are corrected, gesturing toward social progress. As a depiction of class struggle and institutional corruption, the conclusion feels frustratingly superficial, never interrogating the deeper economic and corporate forces that maintain such a system.

Audiences were unprepared for Kathryn Bigelow’s ferocious depiction of a society consumed by spectacle and desensitised to suffering. Blending cyberpunk thrills with an unflinching commentary on racial tension and institutional corruption, Strange Days was both ahead of its time and too prescient for mainstream acceptance. Unfortunately, it was a commercial disaster upon its release, grossing a paltry $17M of its $42M budget.

Moreover, its underwhelming box office performance has contributed to its obscurity, limiting its circulation on home media and cementing its status as a cult artefact. Yet, it continues to endure because it’s simultaneously a visceral thriller and a bleak reflection of society. Bigelow dares to confront the moral and psychological costs of voyeurism, technology, and systemic violence that many of her contemporaries dared to attempt. It stands as a stark reminder of the responsibilities that come with technological power and the need for reflection amid rapid change, a message that’s more relevant today than it was in the ’90s.

USA | 1995 | 145 MINUTES | 1:78:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • SPANISH

director: Kathryn Bigelow.

writers: James Cameron & Jay Cooks (story by James Cameron).

starring: Ralph Fiennes, Angela Basset, Juliette Lewis, Tom Sizemore, Michael Wincott, Vincent D’Onofrio, William Fichtner & Josef Sommer.