SCHINDLER’S LIST (1993)

Steven Spielberg's celebrated Holocaust film tells the story of an entrepreneur in Nazi-occupied Poland and his attempts to save local Jews

Steven Spielberg's celebrated Holocaust film tells the story of an entrepreneur in Nazi-occupied Poland and his attempts to save local Jews

While Steven Spielberg may be known for dinosaur movies, he’s directed twice as many films about World War II. This shows a depth to his filmography that some might not expect. Saving Private Ryan (1998) may be the most popular of these war films, but Schindler’s List stands as his most ambitious. Released the same year as Jurassic Park (1993), Schindler’s List helped Spielberg move past the lukewarm reception of Always (1989) and Hook (1991). It also held personal significance, being the first of his movies to prominently explore his Jewish heritage, a theme he revisited in last year’s The Fabelmans (2022).

Schindler’s List stands out for achieving both box-office and critical success, a feat attained by only a handful of other Holocaust films like Sophie’s Choice (1982) and Life is Beautiful (1997). This success is remarkable considering the immense difficulty of portraying the Holocaust in commercial cinema. The subject has proven so daunting that the “Holocaust movie” can barely be considered a sub-genre, and the most celebrated examples—Alain Resnais’s Night and Fog (1956) and Claude Lanzmann’s epic Shoah (1985)—have been documentaries confined to the arthouse.

Schindler’s List, though, is the film that comes closest to breaking that pattern—and Spielber’s ability to treat the Holocaust dramatically while rarely succumbing to the traps of melodrama or sentimentality surprised many. The final scenes, however, often face justified criticism of over-gilding the lily.

Several esteemed directors, including Billy Wilder (whose parents perished at Auschwitz), had considered adapting Thomas Keneally’s 1982 Booker Prize-winning novel Schindler’s Ark. Keneally had even written a first draft screenplay himself. However, Spielberg opted for an adaptation by Steven Zaillian, who had already written two well-received films, The Falcon and the Snowman (1985) and Awakenings (1990), and would later collaborate with Martin Scorsese on The Irishman (2019). Zaillian’s script, lauded for its focus on Schindler’s moral evolution, ultimately resonated more with Spielberg than Keneally’s draft.

Keneally’s novel occupies a liminal space between fiction and non-fiction, oscillating between conventional storytelling and passages resembling historical writing. Similarly, Schindler’s List, though far from a documentary, echoes this approach through its hesitance to delve deeply into individual characters. Their actions often hold greater weight than their inner lives, requiring us, as with history, to judge them by their deeds rather than their hidden natures. While this approach may leave some characters seeming opaque, it arguably aligns with a film about something as impossible to fully make sense of as the Holocaust.

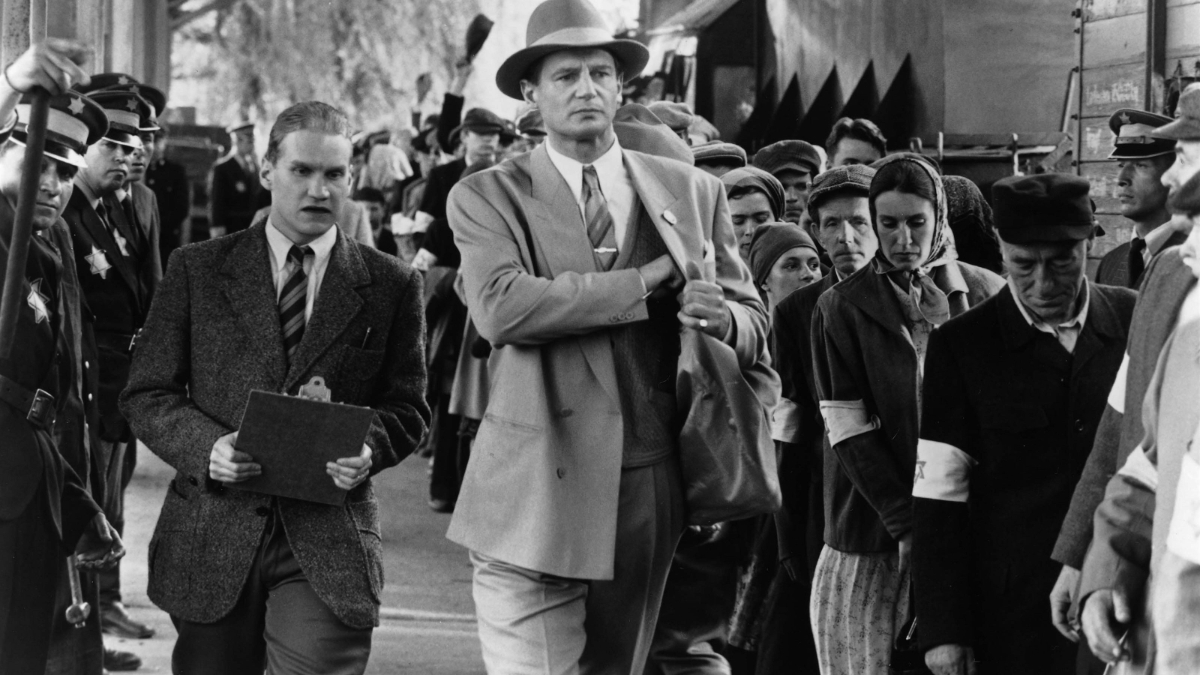

The story begins in Krakow, Poland, in 1939, shortly after the German invasion, and quickly establishes the character of Oskar Schindler (Liam Neeson)—a German (he’d been born in what was then Austria-Hungary) but an invader of a different kind, a civilian entrepreneur. The film establishes him as a party animal, too (in a telling later montage where he is interviewing potential typists, he is not interested in those who are competent but unattractive), and there is no indication at this stage that he has any particular interest in Poles or Jews or for that matter Nazis one way or the other—for him, the war is a business opportunity, one that can make “all the difference in the world between success and failure”.

Schindler’s List then leaps to 1941 with the Krakow Ghetto’s creation, where the city’s Jews are brutally confined. Schindler is running an enamelware factory now, and the gratitude of the old Jew Löwenstein (Henryk Bista) for giving him a job may sow the seed of an idea in Schindler’s mind; but the Holocaust, although it’s been mentioned briefly and we’ve seen an ominous train, is still only on the fringes of the film.

Not until about 50 minutes in does one of the most effective, albeit brief, scenes in Schindler’s List drive its message home. The Nazis’ plunder from murdered Jews—piles of eyeglasses, then a jolting revelation for the Jewish appraiser (shared by the audience)—teeth retained for their fillings. It’s around this point that we finally meet Amon Goeth (Ralph Fiennes), a local SS commander, cruising through the Ghetto in a car. He serves as Schindler’s dark reflection for the rest of the film, a German consumed by evil for reasons as inscrutable as Schindler’s decision to start saving as many Jews as he can. The parallel is emphasized by a cutting edit: Goeth shaving, then Schindler, mirroring their contrasting choices.

In his business and, unofficially, his humanitarian enterprise, Schindler is assisted by the film’s third main character, Itzhak Stern (Ben Kingsley), a Jewish accountant who finds himself largely running Schindler’s firm while his boss concentrates on placating the Nazi authorities and convincing them that he needs to employ all these Jews for essential munitions production.

While the seed of the idea might have already been planted in Schindler’s mind, it’s the 1943 “liquidation” of the Krakow Ghetto—the mass transfer of Jews to concentration camps—that pushes him to make working in his factory one of the few available lifelines for Krakow’s remaining Jews. “They say no one dies here,” pleads a young local woman, Regina (Bettina Kupfer), as she implores Schindler to employ her parents in his workforce. As time passes, he grows bolder in his efforts, even influencing Nazis to hose down overheating railway cars transporting prisoners. Then, about an hour before the film’s conclusion, the titular list finally materializes—the titular list containing the names of Jews who’ll be saved from the camps by working at Schindler’s new factory.

While Schindler’s List boasts a large ensemble cast, two figures undeniably dominate the narrative: Schindler and Goeth. The Jewish population, as a collective entity, could arguably be considered a third major player, even though Stern receives the most individual screen time among them. This distinction underscores that the film extends far beyond just Schindler’s personal story.

Despite his near-constant presence, Schindler often occupies a secondary role. His character is eclipsed, to a large extent, by his actions, by what Stern proclaims as the “absolute good” of rescuing over a thousand souls from the Holocaust. Neeson plays him appropriately, as a man who keeps any complexities well hidden, and as a person he remains something of an enigma to the end of the movie.

Goeth remains an enigma, though for contrasting reasons. He can be seen as both intelligent and, in some ways, even amiable, yet he commits unprovoked acts of violence with chilling ease. Inured to the horrors of the camp, he’s come to view the burning of bodies as merely a tiresome chore. Witnessing his paradox unfold is chilling: first, he orders the execution of a Jewish engineer who dares to warn him of structural flaws in a camp building, only to later implement her proposed repairs. Faced with Schindler’s suggestion that resisting violence can be its own form of power, Goeth seems momentarily intrigued, like a child captivated by a new toy. He indulges in a fleeting display of “benevolence” by forgiving a boy’s minor offence—and then shooting him nonetheless.

“The more you see of the Herr Kommandant,” Helen (Embeth Davidtz) observes of Goeth, “the more you see there are no set rules you can live by. You cannot say to yourself, if I follow these rules, I will be safe.” This sentiment is poignantly echoed in one of the most powerful passages of Fiennes’s mesmerising performance: a monologue delivered to Helen where he seems at first utterly reasonable and empathetic, then turns suddenly violent. Fiennes subtly implies that at least some of this volatility stems from Goeth’s self-doubt—a flicker hinted at when he examines himself in a mirror. Beneath his dandyish self-regard, we suspect, lies a man just as baffled as we are by his capacity for evil.

While Schindler’s List takes artistic license with historical figures, the core characters remain grounded in reality. Both Goeth and Schindler were real people (Goeth was executed for war crimes in 1946). However, Stern’s film persona is a composite, drawing elements from other figures besides the real Stern. Kingsley’s masterful performance breathes life into the character, crafting him as a keen-witted observer who defies expectations of Jewish submissiveness with pointed remarks, his confidence gradually blossoming as he interacts with Schindler as an equal. Stern’s dedication to the business seems to rival even Schindler’s own. “I’ve worked too hard” for it to fail, he asserts.

Equally strong in smaller roles is the aforementioned Embeth Davidtz as Helen, who makes the most of a character who speaks little. Despite minimal dialogue, she conveys a powerful sense of suppressed thoughts and emotions, a burden borne reluctantly for self-preservation. Hans-Michael Rehberg’s portrayal of Rudolph Hoess, the Auschwitz commandant, is a more overt display of sinister intention compared to Goeth’s. He is shot in shadow, while the horror of Goeth’s behaviour often comes from it happening in broad daylight in pleasant domestic circumstances. This stark contrast invites a fascinating interpretation: could Schindler, Goeth, and Hoess be seen as positions on a spectrum, traversing from a desire for good, through warped moral flexibility, to the abyss of true evil?

Neeson and Fiennes were both nominated for Academy Awards; neither won, but Fiennes did pick up a BAFTA award and Schindler’s List in any case swept many of the major categories at the Oscars, including ‘Best Picture’, ‘Best Director’, ‘Best Adapted Screenplay’, and ‘Best Original Score’.

John Williams’s music is, indeed, crucial to the film’s impact, even if it’s sometimes overshadowed by his more overtly heroic or crowd-pleasing scores. Incorporating some elements of Jewish music, he consistently opts for restraint and simple orchestration. A case in point is the scene where Schindler’s female employees enter their new factory towards the film’s conclusion: delicate textures and an absence of grand orchestral swells imbue the moment with a poignancy that would feel sentimental if overdone.

Cinematographer Janusz Kaminski won an Oscar too, for the first of his many collaborations with Spielberg (they’ve made nearly 20 movies together since); as with Williams’s score, his highly mobile camera is effective in drawing us into the settings and the action while not drawing attention to itself.

Along with its powerful visuals, Schindler’s List also shines in its subtle use of editing (earning another Oscar for Michael Kahn). Sometimes, cuts are stark and impactful, like transitioning from a celebratory party song to the jarring march of soldiers. Other times, the action itself carries the weight of emotion, leaving words unnecessary. We see naked Jews forced to run through mud, a jarring contrast to the schmaltzy German song playing on the gramophone. Similarly, Jewish children, singing happily yet heartbreakingly, are driven away in trucks, leaving their mothers in a desperate, frantic panic.

The most famous visual aspect of the movie, however, is undoubtedly the girl in the red coat.

While mostly filmed in black-and-white, Schindler’s List opens with a burst of colour depicting a Jewish family and closes with Jews years later visiting Schindler’s grave, echoing the ending of Saving Private Ryan. So Spielberg’s decision to highlight a single individual, credited as Red Genia and played by Oliwia Dabrowska, naturally draws attention.

She appears first during the liquidation of the Ghetto, where the camera follows her for a while as Schindler watches events unfold on the streets of Krakow; at this point he’s safely detached from them on horseback and high ground, not committed yet to his mission. And she then appears a second time, much more briefly, in an even grimmer later scene.

What are we to make of her? Surely she’s more than a directorial flourish? Spielberg himself has said that the way she stands out from the crowd represents the way that the Holocaust was already—long before the end of the war—well-known to Allied governments, who nevertheless did little to counter it: “It was as obvious as a little girl wearing a red coat, walking down the street, and yet nothing was done to bomb the German rail lines. Nothing was being done to slow down… the annihilation of European Jewry. So that was my message in letting that scene be in colour.”

While the true explanation might be bizarre, it’s hard to believe any audience member would grasp the symbolism, especially given the film’s limited scope focusing on Schindler’s immediate world. The Allies and the broader context barely register in Schindler’s List. Therefore, interpreting Red Genia as symbolizing personalisation feels more fitting. Her first appearance arguably marks the moment when Schindler truly comprehends the human cost of Nazi persecution, shifting from the abstract to the real. Additionally, interpreting colour as representing life and hope, contrasted with the black-and-white’s association with death and despair, offers a more accessible symbolic reading.

Red Genia’s effect on the cumulative power of Schindler’s List is ultimately a matter of personal response. Still, the film is not flawless. Even a master like Spielberg can make missteps, as evidenced by a scene in his film War Horse (2011), where a moment that should have been the movie’s emotional core was undermined by comedy.

Many of the criticisms levelled at Schindler’s List are general, more concerned with the very nature of a film on this subject than any specific aspect of this particular one. Some question whether we should seek uplift from the Holocaust—film critic David Thomson offering faint praise by calling Schindler’s List “a decent way of telling the dire story with a positive attitude.” Others argue that fictional films shouldn’t be made about the Holocaust at all. This exceptionalist view holds that the Holocaust was not just a particularly large (and recent) example of man’s pervasive inhumanity to man, but something qualitatively different from other atrocities, something that cannot be captured on film.

Spielberg’s movie has also been criticised for being emotionally exploitative, and up to a point, the charge holds weight. However, its emotional impact is undeniable, even if some find it manipulative. Additionally, the film has been accused of focusing primarily on non-Jewish characters. However, this claim only partially holds, as Schindler did exist, and nearly every other sympathetic character is a Jew.

More validly, criticism could be raised over the film’s portrayal of the more minor Jewish characters. They’re often presented as being rather naive, and their depictions frequently border on stereotypes that are portrayed as soulful, indomitable, or comical. The scene of Jewish black marketeers meeting in a Catholic church has clear parallels to the Biblical money-changers in the temple, although Schindler himself displays similar avarice.

In a particularly harrowing scene, Spielberg, known for his masterful manipulation of audience emotions, appears to take viewers to the brink of witnessing the gassing of Jewish prisoners in a concentration camp. This act, rarely depicted on film, would undoubtedly be excruciating to watch. Yet, at the last minute, Schindler’s List pulls back from portraying this central horror of the Holocaust. This decision creates a conflicted impression, suggesting a desire for emotional impact while skirting explicit brutality.

The film also stumbles in a few minor areas. A scene of Jewish prisoners speculating about the Holocaust in a camp barracks feels didactic and unconvincing. Similarly, the crowd of Germans and Jews listening to Winston Churchill on the wireless at the end seem to manage so without a translator, somewhat implausibly.

These misgivings large and small notwithstanding, though, Schindler’s List is a masterful film.

The acting of Neeson, Fiennes, and Kingsley in the three main roles, and Williams’s music, are only some of the film’s most obvious strengths. The pacing is superb—the viewer might well feel guilty that the liquidation of the Ghetto is so thrilling purely as cinema, and critic Anthony Lane is surely wrong when he argues that the film’s “sense of historical duty weighed heavily on the body of the action.”

Lane contends that Schindler’s List is hampered by its self-conscious awareness of being “a Holocaust film.” I argue the opposite is true. The film masterfully balances its sombre themes with moments of hope and humanity. It adeptly portrays the gradual unfolding of the genocide, not as a singular monolithic event, but as a series of escalating injustices that crept up on many, initially undetectable in their daily lives. This insidious nature is captured in the poignant question posed by a wealthy Jewish man to his wife after their forced relocation from their luxurious home to the cramped confines of the Ghetto: “How on earth could it possibly be worse?” The question hangs heavy in the air, foreshadowing the escalating horrors to come.

Spielberg’s masterful direction and Zaillian’s sharp writing guarantee an almost impeccable clarity of narrative. The one slight exception is the brief appearance of Josef Mengele, (Daniel Del Ponte), in a scene where he seeks human subjects for his medical experiments. This easily missed moment unfortunately doesn’t quite mesh with the film’s overall flow.

Digressions from the main story, like the disturbing scene where a man is spared execution only because Goeth’s sidearm malfunctions, add a rich sense of time and place without feeling disruptive. Even the occasional surprising moments of humour, such as the old Steiner sisters saying their surname in unison, land gracefully despite their unexpectedness.

Schindler’s List is not a film with a “message”, in the sense of saying anything new or radically different about the Holocaust. But why would it need to?

While it hints at broader themes like the concept of the “good German” embodied by Schindler, the film wisely doesn’t attempt to encompass the entirety of the Holocaust. Instead, it focuses on the compelling story of Oskar Schindler and the Jews he saved, offering glimpses into the complexities of human behaviour during dark times. We see through the young girl’s callous cry (“goodbye Jews”) a chilling echo of Polish anti-Semitism and the suggestion that many weren’t consumed by rabid hatred but simply unquestioningly absorbed prejudice is perhaps even more unsettling. For the most part, though, it is wisely not even trying to be about the entirety of the Holocaust: the story of Oskar Schindler and “his” Jews is more than enough, told so memorably.

Spielberg’s movie largely avoids dwelling on the extermination camps, the Holocaust’s most notorious feature, while subtly referencing them throughout. This oblique approach is one of its many strengths, helping the film achieve what few others have. Though it focuses on a small slice of history, it vividly reminds us of the broader tragedy.

USA | 1993 | 315 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | BLACK & WHITE • COLOUR | ENGLISH • GERMAN • HEBREW • LATIN • POLISH • YIDDISH

director: Steven Spielberg.

writer: Steven Zaillian (based on the novel ‘Schindler’s Ark’ by Thomas Keneally).

starring: Liam Neeson, Ben Kingsley, Ralph Fiennes, Caroline Goodall, Jonathan Sagall & Embeth Davidtz.