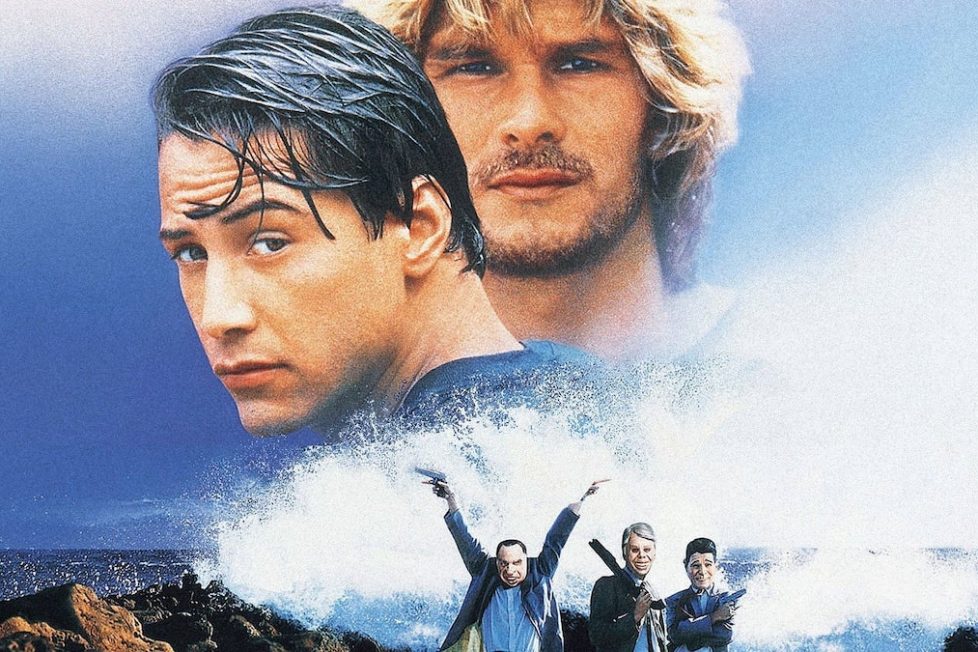

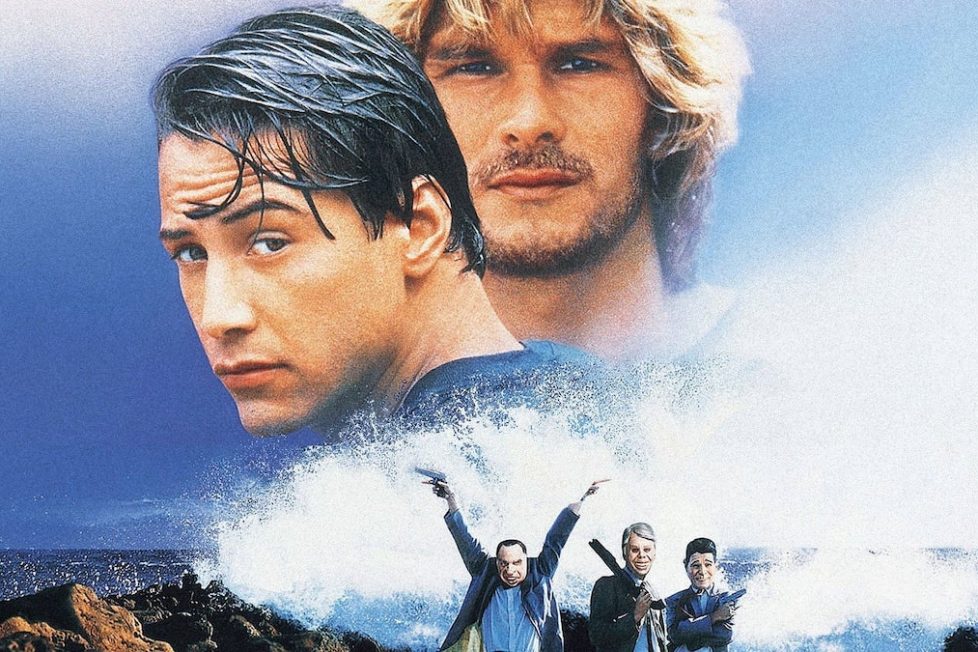

POINT BREAK (1991)

An FBI agent goes undercover to infiltrate a gang of surfers who may be bank robbers

An FBI agent goes undercover to infiltrate a gang of surfers who may be bank robbers

Critics at the time tended to see Point Break as a heavy-on-action spectacle that was light on story and character. Decades later, however, the greater reputation of director Kathryn Bigelow—after Strange Days (1995), The Hurt Locker (2009), and Zero Dark Thirty (2012)—has made it ripe for reassessment, bringing to the fore not only Bigelow’s undoubted technical acumen but also its aesthetic and themes.

Point Break certainly is an action movie, perhaps an action movie par excellence, with all the super-rapid camera movement and big physical set pieces that implies. Two sequences in particular (an FBI raid on a group of surf Nazis, and an extended chase in cars and on foot), were amongst the best of their kind in the early-1990s.

But at the same time, it’s also a parody of action movies. Consider its often testosterone-laden dialogue, its ridiculously irritable FBI director Harp (John C. McGinley), and such downright comic notions as Agent Utah (Keanu Reeves) dressed in regulation dark suit carrying a lurid surfboard under his arm, or a Nazi with the uber-right-wing name of Bunker Weiss. Not to mention the way it sneakily undermines the assumptions of the genre where gender’s concerned. Reeves, looking decidedly androgynous, falls in love with the decidedly boyish Tyler (Lori Petty) and is clearly also falling into platonic love with pixie-like surfer Bodhi (Patrick Swayze).

Bigelow and screenwriter W. Peter Iliff set up the story briskly and without unnecessary complication. It’s Utah’s first day on the job as an FBI agent in California and he’s paired with a more experienced older agent, Pappas (Gary Busey), who resents him initially but inevitably becomes a pal. They’re assigned to the case of a prolific bank-robbing gang known as ‘The Ex-Presidents’ after the caricatured rubber masks they wear of Nixon, Reagan, etc. Clues ranging from chemical residues to a tan line noticed on CCTV suggests the perpetrators might be surfers, so Utah goes undercover to infiltrate their community.

In superficial narrative terms, Point Break proceeds from there pretty much as one would expect, though it does spring one substantial surprise around the midpoint. Its interest, however, lies not so much in what happens but in Bigelow’s rendering of it. For as well as being a film of vigorous, dynamic action sequences, Point Break is also an unashamedly sensuous one. Bigelow and cinematographer Donald Peterman love faces and bodies (especially Swayze and Reeves), and they revel in light that glitters on the sea or bathes the desert in gold.

A long skydiving sequence toward the end is barely necessary to the plot, but it affords Bigelow the chance to depict the main group of characters as almost depersonalised units in a composition that’s ecstatic for its own sake. Surfing silhouettes serve the same purpose. The skydiving sequence is followed by a beautiful shot of parachutes collapsing into water, its non-functional gorgeousness taking Point Break a considerable distance from the action genre norms. The score by Mark Isham, who again wouldn’t be the obvious choice for most action movies of the time, is particularly successful in enhancing the skydiving sequence.

Thematically, too, Point Break goes beyond convention, pushing the familiar idea of the nonconformist cop to its limits. In atmosphere it clearly contrasts the world of the surfers and the world of the FBI throughout; something made apparent from the beginning, where Bigelow cuts between slo-mo surfers on rippling ocean waves (joyous, possibility-filled water) and Utah doing target practice in the rain (annoying, restricting water).

The question, of course, is which world he’ll gravitate to, and for all Reeves’s limitations as an actor his casting works perfectly in this respect. He simply looks more like a surfer than an FBI agent, which constantly reminds us of his dilemma. “l can’t do this,” Utah says when Bodhi lures him into a compromising position. “Sure you can,” replies Bodhi—whose name means “enlightenment” and who represents all the spiritual wisdom the materialist Utah has yet to gain. “Who knows? You might like it.”

Indeed, the film hints far earlier that not only Utah, but Pappas too, may not be well-suited to the buttoned-down world of government investigations. Their identification of the Ex-Presidents is based on instinct, which is anathema to the procedure-driven Harp.

Reeves was the lesser of the film’s two male leads at the time, having only recently come to prominence with Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989)—a film as unlike Point Break as imaginable—and with major hits like Speed (1994) and The Matrix (1999) still in his future. So it was Swayze, already established through big movies such as Dirty Dancing (1987) and Ghost (1990) who took top billing; and although we tend to think of Point Break as a Reeves movie today, Swayze’s the one who impresses. He’s pixie-like, oddly precise in his movements, and comes to quietly dominate every scene he’s in.

Petty makes a lot of a subsidiary role as Tyler, crafting a character sufficiently intriguing that it’s a pity she vanishes for the latter parts of the movie. Reeves, meanwhile, isn’t bad in the sense of giving the wrong impression of his character, he just doesn’t give much impression at all—alternating between what Tyler calls his “intense scowl” and a rarer grin, which is exactly the same when he’s being insincere as when he’s pouring his heart out. He’d perhaps become a somewhat better actor later in his career, but he wasn’t there in 1991.

But this isn’t really an actors’s movie, anyway. It’s all about the totality of the experience rather than any individual character, and for Bigelow it was a breakthrough after her well-received but commercially ho-hum Near Dark (1987) and Blue Steel (1990). Point Break was a mid-ranking box office success (in a year with strong competition like Terminator 2: Judgment Day and The Silence of the Lambs) and paved the way for her to thrive—not only as a rare female mainstream director, but even more unexpectedly as one specialising in fast-moving action movies, described by film writer Mark Salisbury as “like a female Walter Hill crossed with Sam Peckinpah.”

Reviewers of Point Break at the time agreed the action works well, but they were more sceptical, or downright negative, about the dramatic value. Since then critical opinion has discovered greater depth in the movie. Academic Sean Redmond, for example, regards it as an iconoclastic “giddy work of art.” Bigelow herself encourages this kind of interpretation, in points echoed by the character Pappas during the film: “The unique thing about surfing is that it kind of exists outside the system, the people that embody it are of their own mind set, they have their own language, dress code, conduct, behaviour and it’s very primal, very tribal. I tried to use the surfing as a landscape that could offer a subversive mentality.”

A 2015 remake was poorly received by audiences, but actually wasn’t a total box-office failure after grossing $133M from a $103M budget. And the original Point Break could easily have been a terrible movie, because in the wrong hands its combination of conventional action elements with its questioning of the action hero’s real nature could have resulted in a jarring compromise; a film with two agendas fulfilling neither.

But it’s to Bigelow’s credit that Point Break functions so well on two different levels. Whether you see it as an action movie with a brain, or a movie about gender and social roles that also happens to contain some action, Point Break is so well-crafted that its two sides co-exist seamlessly and even enhance one another. It’s so much more than just that Keanu Reeves surfing flick.

USA • JAPAN | 1991 | 122 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Kathryn Bigelow.

writer: W. Peter Iliff (story by Rick King & W. Peter Iliff).

starring: Patrick Swayze, Keanu Reeves, Gary Busey & Lori Petty.