SHERLOCK, 4.3 – ‘The Final Problem’

If this is the end of Sherlock then, I have to say, so be it. In this fourth series, it has eschewed the mythology of Holmes and Watson that underpinned the series since 2010, to plough a self-indulgent path away from its source material. How ironic then that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s own tale “The Final Problem”, itself intended to send Holmes out in a blaze of glory, should be the title and purpose of this episode. However, despite his efforts to do so Doyle couldn’t escape his creation. In 1902, eight years after publishing “The Final Problem”, under pressure from his readers, he wrote “The Hound of the Baskervilles”. In 1903, he brought Holmes back from his own supposed death at Reichenbach in “The Adventure of the Empty House.”

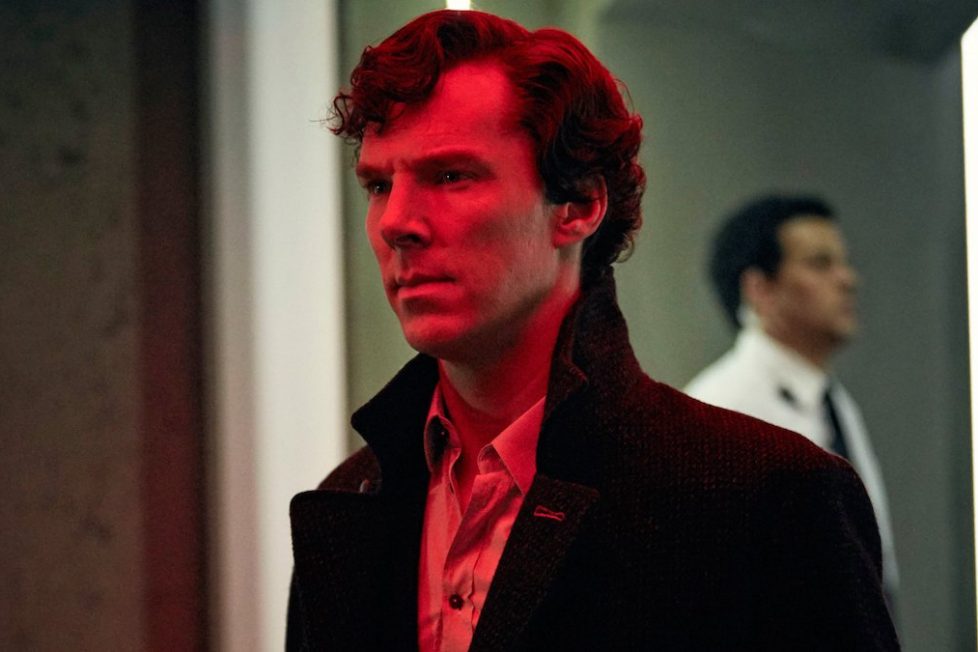

Whether Sherlock’s creators Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat will return to the scene of the crime to bring Holmes (Benedict Cumberbatch) and Watson (Martin Freeman) back — very much dependent on the work diaries of the two leads it seems — then I’d ask them to pause for thought. “The Final Problem” offers both closure and an attempt to return the show to its core appeal; that of Holmes and Watson solving unusual cases in contemporary London. However, I wouldn’t encourage them to carry on in the vein of “The Final Problem”.

Gatiss recently responded (in verse) to a journalist criticising “The Six Thatchers”, refuting that the Holmes character was turning into Bond or Bourne. My own review of “The Six Thatchers” argued that it was the aesthetic of the series, rather than its eponymous character, that was now aping those franchises. “The Final Problem” repeats these attention-grabbing genre tropes, but the biggest issue here is how Gatiss and Moffat force the the characters through an emotional purification as they attempt to resolve as many narrative loose ends as possible, often sacrificing sense and clarity along the way.

Let’s begin with last week’s cliffhanger where Watson was about to be shot by Eurus (Sian Brooke), the therapist turned vengeful Holmes sister. Typical of Moffat, he textually smooths out the dilemma and the cliffhanger’s function is made redundant as Holmes and Watson appear unscathed in the pre-titles sequence. Watson was only shot with a tranquiliser dart, it seems. On that score, this is an episode filled with images of characters plunging into unconscious states or emerging out of reveries filled with memories and suggests we’re slipping in and out of a dream.

Structurally, the finale begins with an eye opening and a little girl finding herself on an aircraft full of passengers about to crash into a city. This immediately establishes the concept of withdrawing into loneliness that powers the episode’s unpacking of Eurus’s history. By the end of the episode, Holmes has solved the riddle and found the lost Eurus, who must open her eyes to escape the nightmare of crashing in a plane. It’s a metaphor for the memory palace gone awry, a psychic shock brought on by traumatic recollections.

Yet, ‘the final problem’ being put into play by Moriarty (Andrew Scott) is also an application of in media res. This is emphasised later by the braggadocio of Moriarty’s arrival in the narrative, that immediately has the audience thinking the master criminal didn’t die, only to have its expectations undercut by the ‘five years earlier’ chyron that appears on screen. In the opening scene on the plane it’s Moriarty who calls Eurus, creating a loop of narrative that stretches back to his visit with her on the island prison of Sherrinford.

Another conceit is Holmes and Watson’s Gothic shenanigans (hiring a clown, for heaven’s sake?), scaring Mycroft (Mark Gatiss) to the point where he confesses to Eurus’s existence. The horror tropes accumulate when Holmes then describes the East Wind turning his sister into a ghost story. Pointedly, it’s not one of Sherlock’s “idiotic cases” that Mycroft is being drawn into. It’s a Gothic tract involving the Holmes siblings and the traumatic childhood incidents that sent them off the rails and to retreat into themselves.

Oscar Wilde is invoked to forewarn us that the truth about Eurus is not going to be straightforward, especially as Holmes has no recollection of her. That’s not surprising, as the whole business of the Holmes siblings is one purely created by Moffat and Gatiss (there was no sister in Conan Doyle’s original stories) and Eurus is a device to try and humanise Holmes. Conan Doyle described Holmes as “as inhuman as a Babbage’s Calculating Machine” and it was Watson who carried the humanising function in the stories. Here, it’s a sister who murdered his best friend that sends Holmes down roads that few other writers have successfully navigated with the character.

As Mycroft declares, “the roads we walk have demons beneath”, and this week Gatiss and Moffat are going to make absolutely sure Holmes walks down them — no matter that, in the end, he becomes a baby friendly best buddy of the Metropolitan Police. I quite like the idea that their fragile sister’s escape into the world is all Mycroft’s fault, using her “deduction thing” and “era-defining genius” for his own ends, and rewarding her with a Moriarty visit as a Christmas present, as it gives the character and Gatiss some interesting moments to play — particularly the darker aspects of family loyalty and brotherly love.

So, we end up popping back and forth into the memories of Eurus’s troubled childhood: plonking Mycroft on a beach, dropping the young Eurus into Baker Street, and then we’re off to Musgrave, the ancestral Holmes home. I don’t know about anyone else, but I thought Holmes’ memory palace visit to Musgrave rather paralleled Bond’s return to Skyfall Lodge, both of them mythic characters returning to their traumatic roots it seems to me. Talking of similarities, let’s not forget that Blofeld turned out to be 007’s adoptive brother in Spectre (2015), and as Eurus determined Sherlock’s “every choice you’ve ever made… every path you’ve ever taken”… for James Bond his nemesis was “the author of all your pain.”

Musgrave nominally refers to Doyle’s “The Adventure of the Musgrave Ritual” and its own riddle that Holmes solves to locate the whereabouts of a missing man who suffocated in a cellar while on a treasure hunt. Elements of this are reworked into this episode’s final act where the odd gravestones seen at Musgrave form the clues (“her little ritual”) to where exactly Holmes will find Eurus and where Watson finds himself chained to the bottom of a well filling with water.

We learn that Eurus was removed from Musgrave for her own protection after she burnt the house down. Moffat and Gatiss also plant a shaggy dog story with an actual dog in it. The name of Sherlock’s dog, Redbeard, has been floating about since “His Final Vow”. Although it seems Redbeard does indeed refer to a dog, when the layers are peeled back in the final act it also refers to pirate games that the Holmes children play, games being yet another Moffat trope, and the dark consequences of childhood isolation.

Eurus, we learn, has been incarcerated in Sherrinford; that secure and secret island installation that clearly isn’t very secure as she’s already popped out, impersonated a therapist, an entrepreneur’s daughter and flirted with Watson on a bus. Uncontainable, that’s our Eurus, and delivering a bomb by drone to 221B Baker Street is also no problem. The details of how she manages to arrange the delivery of a patience grenade don’t trouble the narrative. However, before the place goes up in flames, we are afforded a very amusing cut to Mrs. Hudson (Una Stubbs) in the flat below hoovering to Iron Maiden’s “The Number of the Beast”. The demon beneath the road is a housekeeper into heavy metal. Suffice it say, in the hyper-real world of Sherlock everyone survives the explosion without a scratch.

By way of sou’wester and fishing boat, they all infiltrate Sherrinford. Sherlock meets his sister in her supposedly secure unit, sawing away on a violin and uttering a torrent of psychobabble during her psychiatric assessments. Except, it’s as secure as the BBC when a Russian television channel manages to leak its content all over the internet. Having brainwashed the governor (Art Malik, in a thankless role), Eurus has the run of the place and has gone to the extravagance of luring Sherlock to her cell, removing the glass, and projecting her voice through speakers to give the illusion of incarceration. By the way, look at the ceiling of her cell, it matches the skylight in the cell designed by Ken Adam for the first Bond film Dr. No. I wonder if Mark Gatiss will respond to that observation in verse this week…

Although Mycroft berates the governor for even attempting to evaluate Eurus, the truth is that Mycroft, in perhaps the stupidest action he ever undertook, gave her the Christmas present of Moriarty’s visit despite the dangers inherent in her ability to compromise and reprogram people. After much interminable pseudo-psychological banter about violin playing, hard drives, and sibling rivalry, Eurus finally gets her long lost brother in her grasp and Watson tumbles that the governor has been compromised. Sherlock is described as “the man who sees through everything” but apparently can’t spot glass missing from her cell, and the hoary old cliche of a central female protagonist depicted as a mad, hysterical angel/monster figure. She’s basically Ophelia to Sherlock’s Hamlet.

The episode then becomes a series of locked room mysteries or, if you prefer, quite expensive recreations of, take your pick, Fort Boyard, The Crystal Maze or The Adventure Game by way of Saw (2004). This is after Andrew Scott briefly drops in for Eurus’s flashback Christmas surprise and chews through his five minutes of screen time to the tune of Queen’s “I Want to Break Free” to put Moriarty’s plan in place. It’s rather unclear but presumably this consists of weaponising Eurus, after finding out who Redbeard is, to fulfil his desire of “Holmes killing Holmes.” Later, he feels it is incumbent upon himself to pop-up on video screens, purely as a sop to those viewers missing his baroque presence in the series.

It all becomes a series of tests to undermine Holmes’ resolve. Does he shoot Watson or Mycroft, how does he save the governor and his wife, what will it take for him to confess to Molly his love for her, which of the three Garrideb brothers is innocent? This is light years away from solving quirky cases in 221 Baker Street and becomes a rather tiresome exercise to demonstrate how Eurus is really off her chump and intends to force Holmes to realise that all his logical decisions must have an emotional context. Holmes turns the tables simply by turning a gun on himself, knowing full well that Eurus will not accept it. After all, she hasn’t told him about Redbeard yet.

So, we end up back at Musgrave Hall with Watson in the well and Holmes in a rather elaborate cell that collapses (rather like the plot, it’s a house of cards) as he finally determines that the little girl on the phone stuck on the plane is actually Eurus communicating from her memory palace. This is revealed to be a convoluted exploration of her guilt about murdering Holmes’ best friend Victor Trevor, the young boy playing Redbeard the pirate in the flashbacks to their not so idyllic childhood. So not only is she the mad woman in the attic, she’s also motivated by that most base of emotions, jealousy.

“The Final Problem” is a bit of a mess and, despite all of its earnest psychological exploration of Eurus’ past, it doesn’t earn the emotional context, the very thing that Eurus is trying to instil in Holmes, that the episode so desperately craves. She’s supposed to be able to re-programme people with the merest glimpse, but she hitches her wagon to Moriarty’s star to exact revenge. But then was it also Moriarty’s posthumous revenge after all that?

For all its tricksy narrative loops, sleek production design, and committed performances, the episode doesn’t deserve to flout its eager self-indulgence and it often plunges into incoherence. Then there’s Mary Morstan’s horribly banal mythologising DVD commentary about “my Baker Street Boys” as we see a happier Holmes and Watson rebuilding the Baker Street flat. We don’t need to be told that Holmes and Watson are legends because we already know. There is, somewhere in the middle of all this, a genuinely good story about surviving trauma (John’s PTSD, the death of his wife, and Sherlock’s retreat into sociopathy), but we only get rare glimpses of it.

Perhaps, it’s best to leave them hurtling out of the entrance to Rathbone Place (a nod to Holmes actor Basil Rathbone of the Universal films), fixed in memory.